Dante Alighieri’s “Inferno,” the first part of his epic poem “The Divine Comedy,” is one of the seminal works of Western literature. Written in the early 14th century, it provides a detailed account of the poet’s imagined journey through Hell, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil.

Introduction

Contents

- Introduction

- Canto I – The Dark Wood

- Canto II – Doubt & Encounter

- Canto III – The Gates of Hell

- Canto IV – The First Circle, Limbo

- Canto V – The Second Circle, Lust (Minos)

- Canto VI – The Third Circle, Gluttony (Cerberus)

- Canto VII – The Fourth Circle, Avarice (Plutus)

- Canto VIII, The Firth Circle, Wrath (Phlegyas)

- Canto IX – The City of Dis

- Canto X – The Sixth Circle, Heresy

- Canto XI – The Lower and Upper Circles of Hell

- Canto XII – The Seventh Circle, Violence I

- Canto XIII – The Seventh Circle, Violence II

- Canto XIV – The Seventh Circle, Violence III

- Canto XV – The Seventh Circle, Violence IV

- Canto XVI – The Seventh Circle, Violence V

- Canto XVII – The Eighth Circle, Fraud

- Canto XVIII – The Eighth Circle, Seduction

- Canto XIX – The Eighth Circle, Simony

- Canto XX – The Eighth Circle, Astrology

- Canto XXI – The Eighth Circle, Evil Authority

- Canto XXII – The Eighth Circle, Corruption

- Canto XXIII – The Eighth Circle, Hypocrisy

- Canto XXIV – The Eighth Circle, Theft I

- Canto XXV – The Eighth Circle, Theft II

- Canto XXVI – The Eighth Circle, Evil Counsel I

- Canto XXVII – The Eighth Circle, Evil Counsel II

- Canto XXVIII – The Eighth Circle, Divisiveness

- Canto XXIX – The Eighth Circle, Falsity

- Canto XXX – The Eighth Circle, Falsifiers

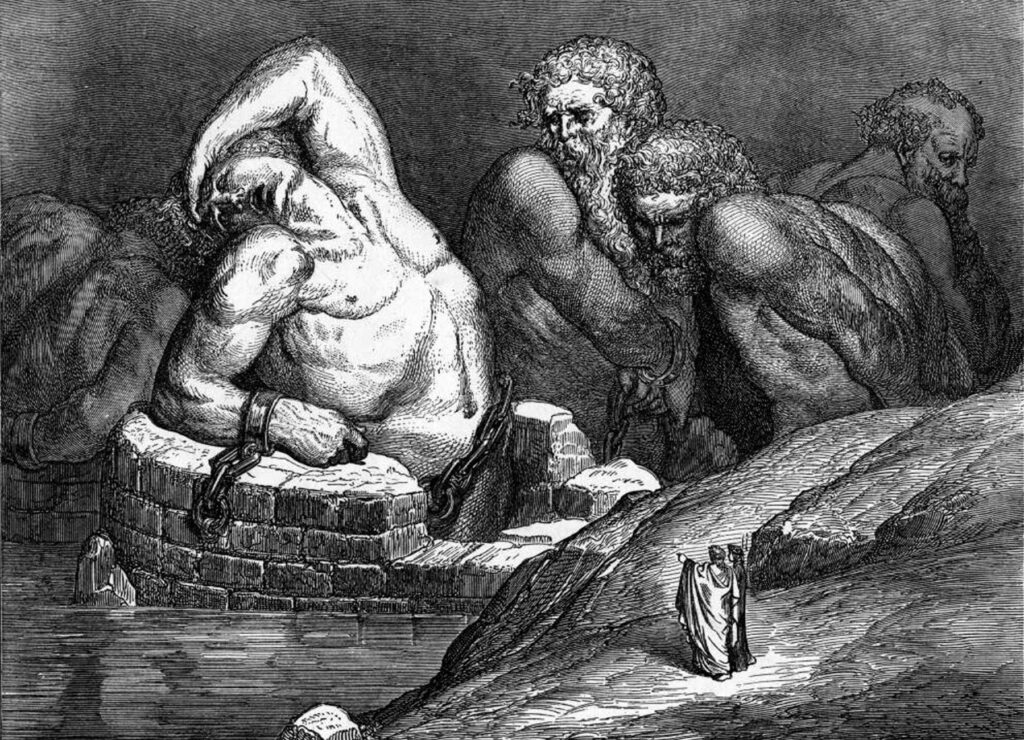

- Canto XXXI – The Eighth Circle, Pride, Rebellion, Treachery

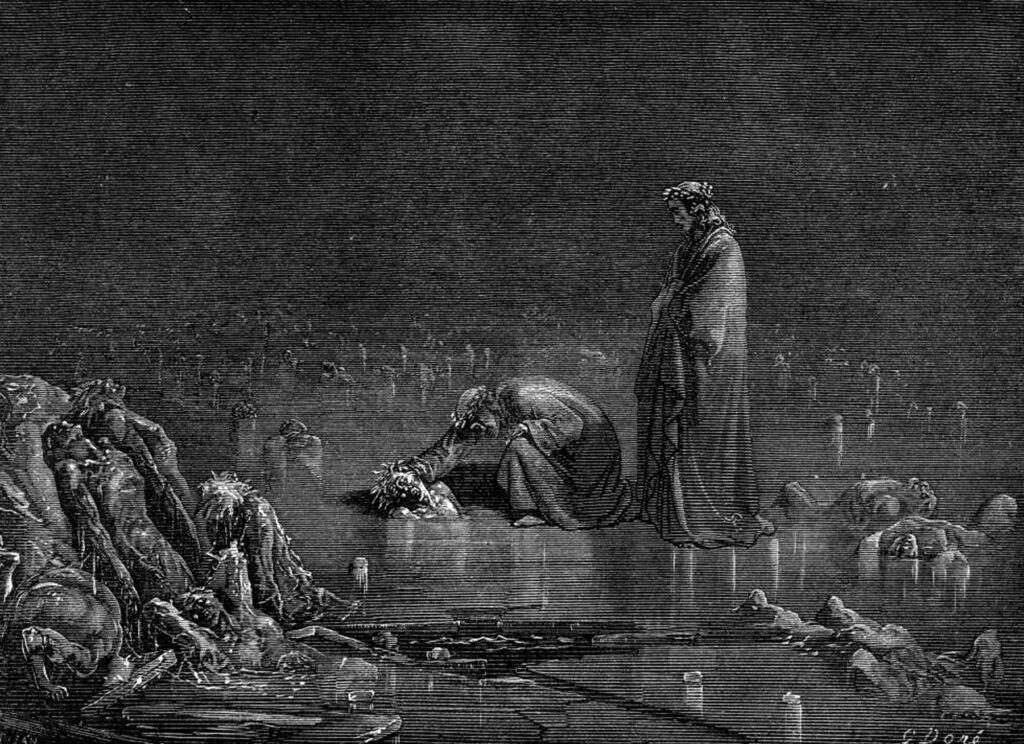

- Canto XXXII – The Ninth Circle, Treason

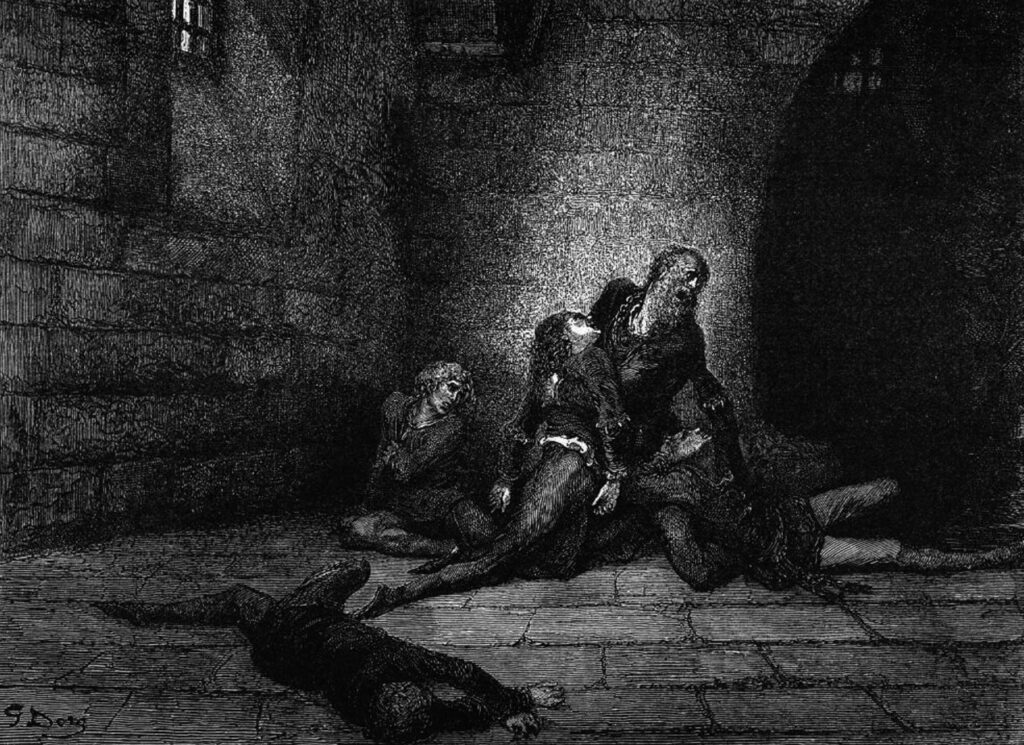

- Canto XXXIII – The Ninth Circle, Treachery I

- Canto XXXIV – The Ninth Circle, Treachery II

The poem opens on the night before Good Friday in the year 1300. Dante himself, a man of middle age, has lost his way in a shadowy forest, representing spiritual confusion and despair. Threatened by wild beasts, he is rescued by the spirit of Virgil, who explains that Dante’s beloved Beatrice (who resides in Paradise) has noticed Dante’s spiritual crisis and has sent Virgil to guide Dante on a journey of spiritual awakening and redemption.

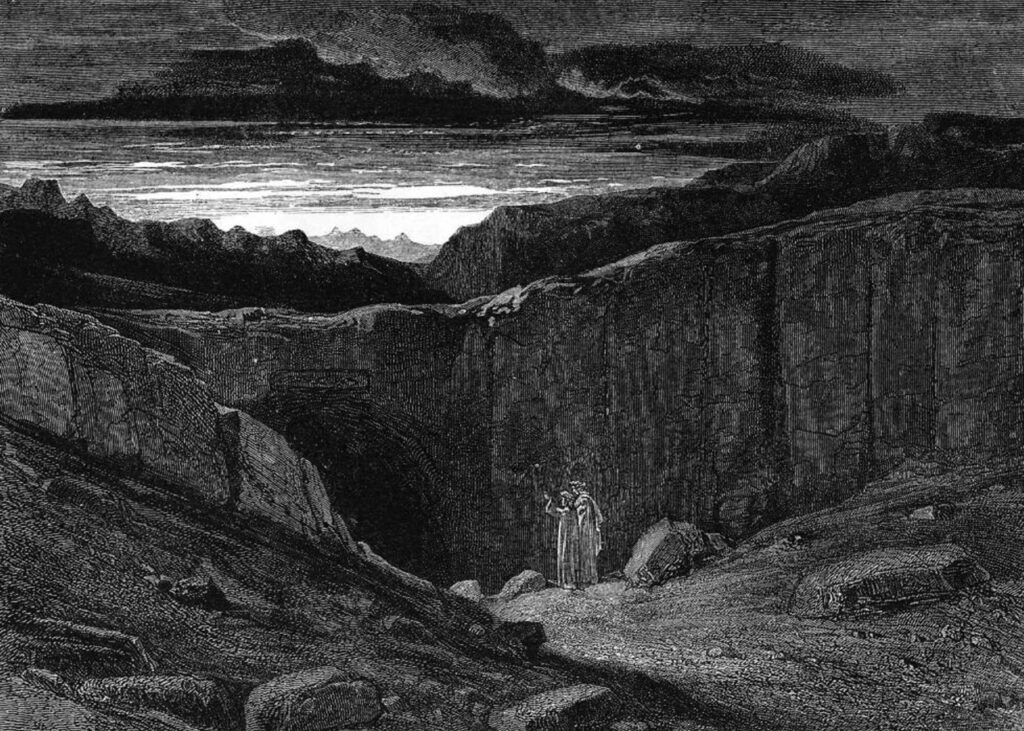

Hell, in Dante’s conception, is a vast, conical pit divided into nine concentric circles, each of which is reserved for the punishment of a particular sin. The descent through these circles forms the main action of the “Inferno.”

In the first circle, Limbo, Dante encounters the unbaptized and the virtuous pagans, who, though not sinful, did not accept Christ. They live in a castle with seven gates symbolizing the seven virtues. Here Dante sees many notable figures from classical antiquity like Homer, Socrates, and Aristotle.

Dante and Virgil descend into the second circle, where lustful souls are tormented in a ceaseless wind, representing the power of lust to blow one about needlessly and aimlessly. Here Dante meets famous lovers like Paolo and Francesca, who tell their tragic tale.

The third circle punishes the gluttonous, who are forced to lie in a vile slush produced by ceaseless disgusting rain. In the fourth circle, Dante finds the avaricious and the prodigal, who are punished by being made to clash against each other with great weights.

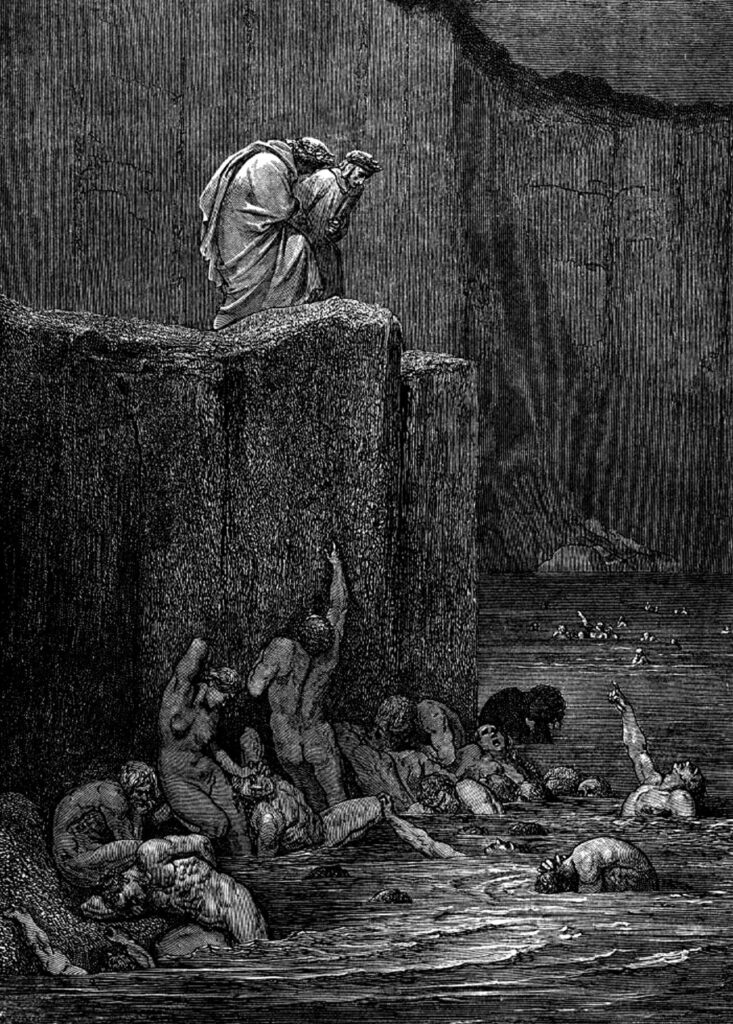

The fifth circle houses the wrathful and the sullen, submerged in the river Styx. The wrathful fight each other on the surface, and the sullen gurgle beneath the water, withdrawn into a black sulkiness which can find no joy in God or man.

Upon reaching the city of Dis in the sixth circle, the poets are initially barred entry, but an angelic messenger arrives and forces the gates open, allowing them to enter. Inside, they find heretics who are trapped in flaming tombs.

The seventh circle houses the violent, divided into three rings. The first ring punishes the violent against neighbors; murderers and war-makers are immersed in Phlegethon, a river of boiling blood. In the second ring, the violent against themselves (the suicides) are transformed into gnarled, thorny trees and fed upon by Harpies. The third ring punishes the violent against God (blasphemers) and Nature (sodomites and usurers), who dwell in a desert of burning sand with a continual rain of fire.

The eighth circle, known as Malebolge, is divided into ten bolgias, or trenches, where different types of fraud are punished, including panderers, seducers, flatterers, sorcerers, corrupt politicians, hypocrites, thieves, fraudulent advisors, sowers of discord, and falsifiers.

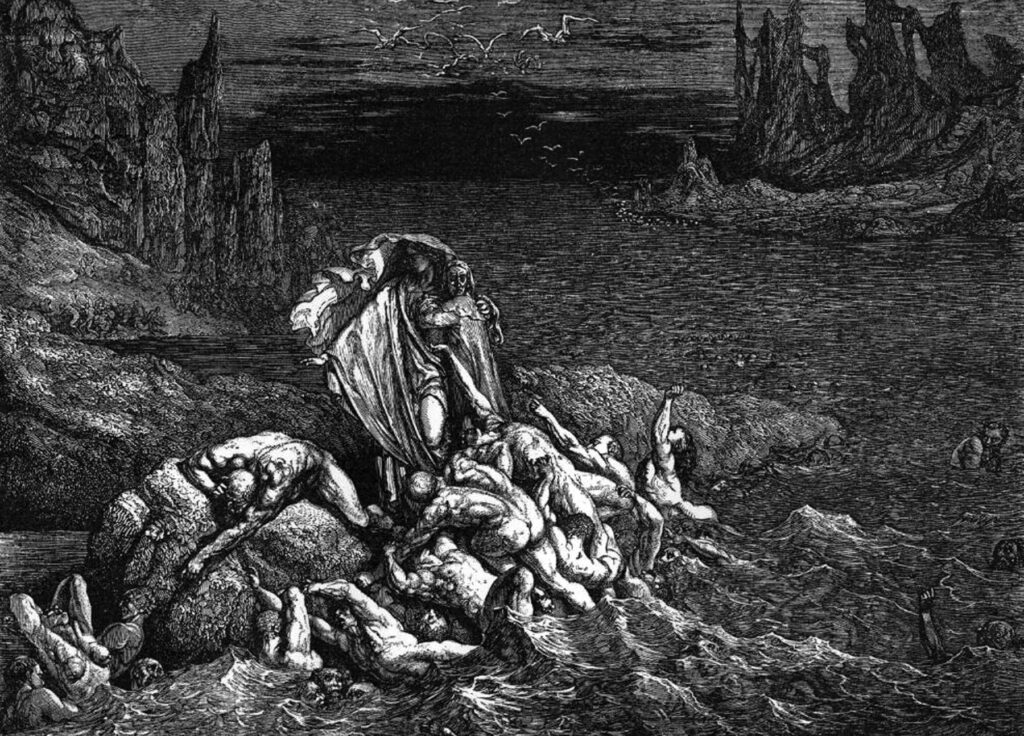

Finally, Dante and Virgil reach the ninth circle, the deepest part of Hell, where treachery is punished. This circle is frozen in the ice of Cocytus, and is divided into four rounds: Caina (for treachery to kin), Antenora (for treachery to country), Ptolomea (for treachery to guests), and Judecca (for treachery to lords and benefactors). In the very center of Hell

Canto I – The Dark Wood

Dante meets Virgil | Dante’s Predicament | Virgil will be his guide through Hell

Inferno, the first part of Dante Alighieri’s epic poem Divine Comedy, narrates the journey of the poet through Hell, guided by the Roman poet Virgil. Canto I sets the stage for the entire journey and serves as an introduction to the poem’s main themes.

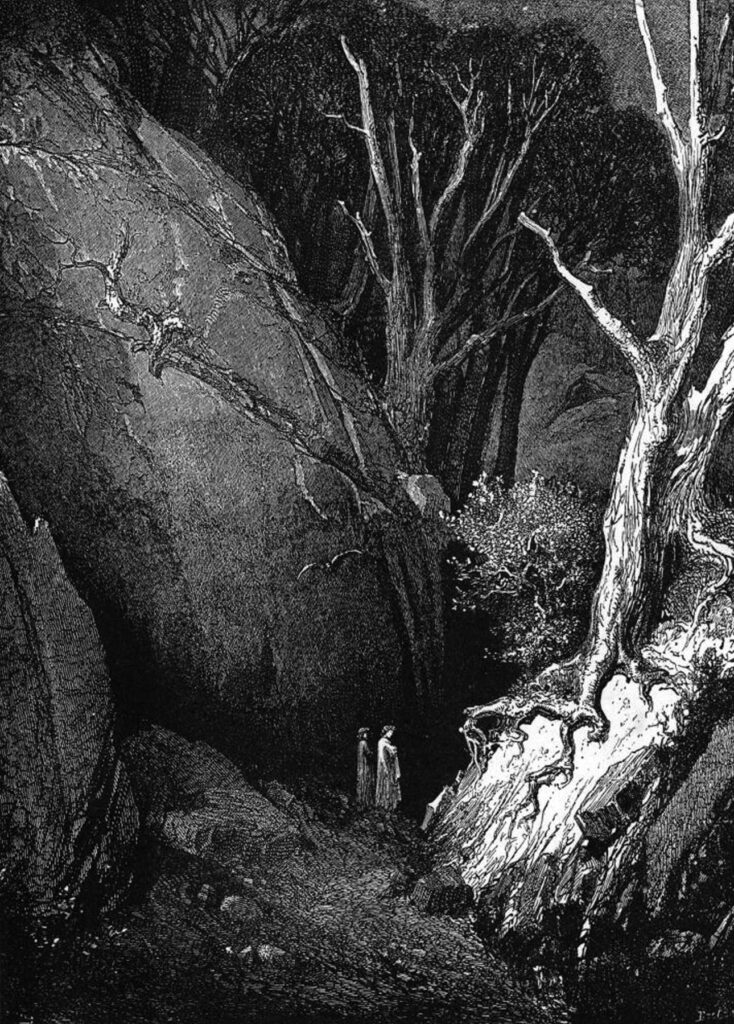

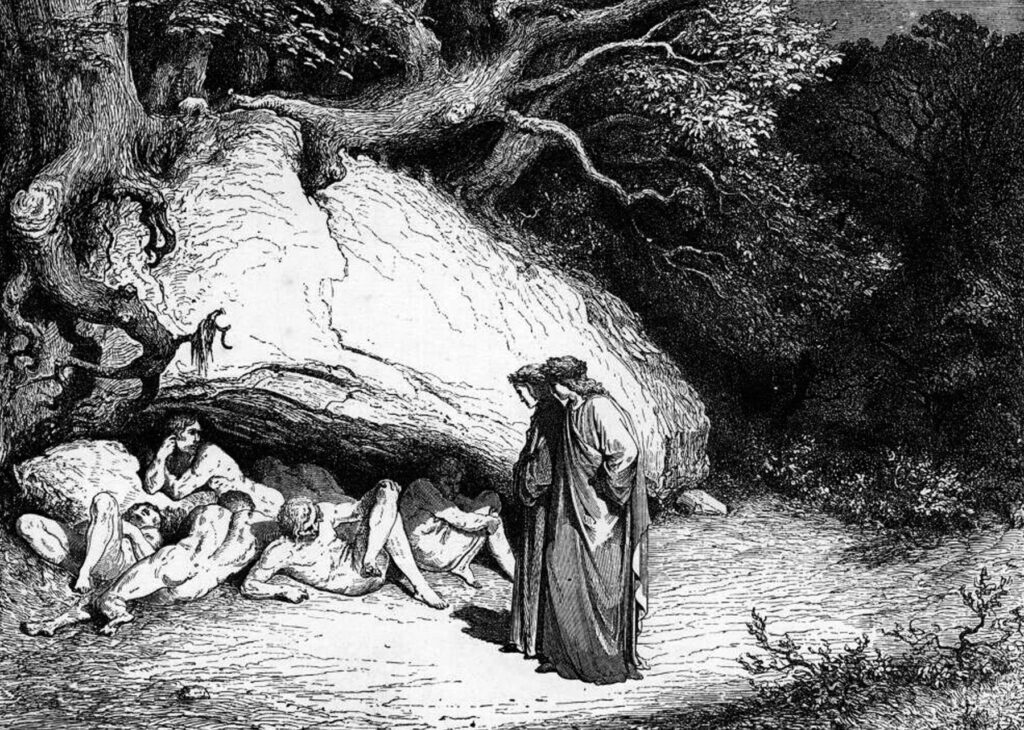

The canto begins with Dante finding himself lost in a dark forest, symbolizing spiritual confusion and despair, at the midpoint of his life (age 35). He is unsure of how he arrived in this predicament, having wandered from the path of righteousness. As Dante attempts to find his way out of the forest, he encounters three ferocious beasts: a leopard, a lion, and a she-wolf. Each beast symbolizes different aspects of human sin – lust, pride, and greed, respectively – and they block Dante’s path, forcing him to return to the dark forest.

Despairing and fearful, Dante is approached by the spirit of Virgil, the renowned Roman poet. Virgil has been sent by Beatrice, Dante’s idealized love, who resides in Heaven. Beatrice has been prompted to aid Dante by the Virgin Mary and Saint Lucia, emphasizing the role of divine intervention in guiding Dante’s journey. Virgil explains that he will be Dante’s guide through Hell (Inferno) and Purgatory, while Beatrice will guide him through Heaven (Paradiso).

Initially, Dante is hesitant and fearful, doubting his own abilities to endure the journey through the realms of the afterlife. However, Virgil reassures him that his journey has been ordained by Heaven and that he is destined to succeed. With newfound determination, Dante agrees to follow Virgil, and together they set forth on their journey through Hell.

In summary, Canto I of Inferno establishes the context for the entire Divine Comedy. Dante, having strayed from the righteous path, finds himself in a dark forest, symbolizing spiritual confusion. He encounters three beasts that represent various human sins and is ultimately guided by the spirit of Virgil, sent by divine intervention to help Dante on his journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. This canto introduces the themes of sin, divine guidance, and redemption, which will be explored throughout the poem.

Canto II – Doubt & Encounter

Dante Doubts His Fitness | Virgil’s Reassurance | Mission Purpose

Inferno Canto II serves as the transition between the introduction of Dante’s journey in Canto I and the actual descent into Hell. This canto highlights Dante’s apprehension and his need for divine intervention, as well as the importance of trust and faith in his journey through the afterlife.

The canto begins with Dante expressing doubt and fear as he prepares to embark on his perilous journey. He questions his own worthiness and abilities, comparing himself to the great heroes of the past, such as Aeneas and St. Paul, who had also ventured into the afterlife. Dante believes that he is not as virtuous or accomplished as these legendary figures and fears that he might not survive the horrors he will encounter in Hell.

Virgil, Dante’s guide, senses his apprehension and reassures him by revealing the divine origins of their journey. He tells Dante that Beatrice, his beloved, has been sent by the Virgin Mary and Saint Lucia to request Virgil’s guidance for Dante. Beatrice herself has been urged by the love of God to ensure Dante’s spiritual salvation. Virgil emphasizes that their journey is willed by Heaven and that divine powers are watching over them.

This revelation strengthens Dante’s resolve, and he finds the courage to continue on his path. He places his trust in Virgil and divine guidance, and the two prepare to enter Hell. As they approach the gates, Virgil reminds Dante to cast aside all fear and hesitation, as their journey has been ordained by a higher power.

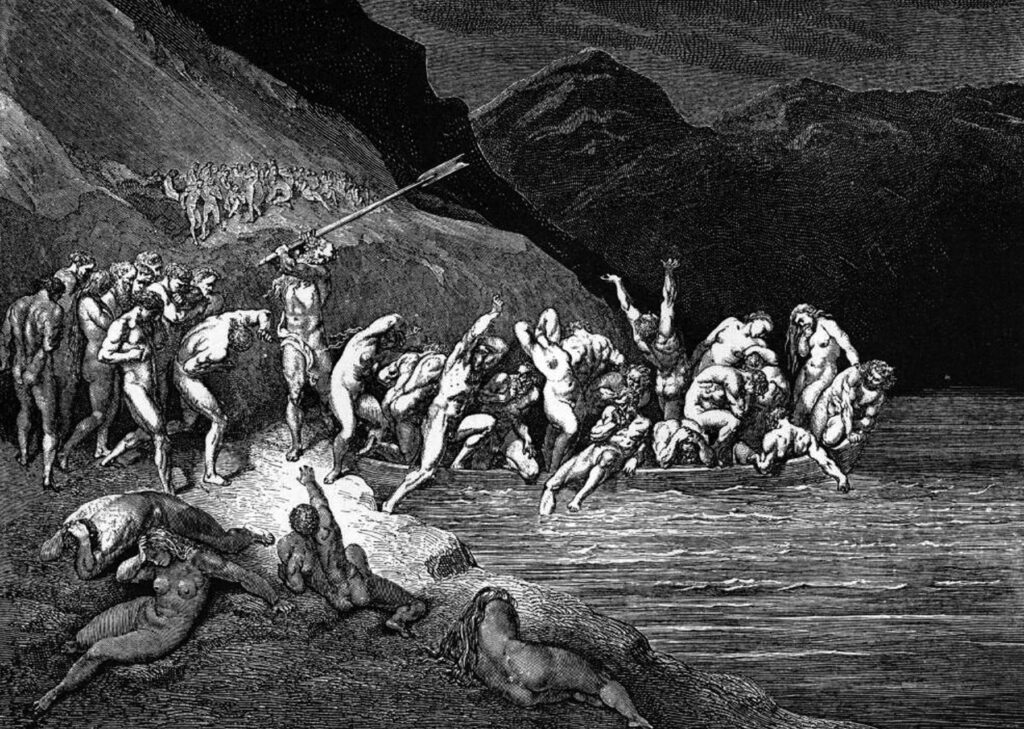

Before they descend, Dante encounters the spirits of the dead who are waiting to be ferried across the river Acheron by Charon, the mythological ferryman of the dead. These spirits represent the souls of those who never chose a side in life, neither good nor evil. This is Dante’s first encounter with the consequences of the choices made in life and their impact on the afterlife.

In summary, Inferno Canto II explores Dante’s initial doubts and fears as he contemplates his journey through Hell. He is reassured by Virgil, who explains that their journey is guided by divine intervention and supported by heavenly powers. Dante’s faith and trust in Virgil and divine guidance are emphasized as crucial for his journey. The canto also introduces the concept of consequences in the afterlife as a result of choices made during one’s life, a theme that will be further developed throughout the Divine Comedy.

Canto III – The Gates of Hell

The Spiritually Neutral & Their Punishment | Charon & Acheron | The Souls of Acheron

Inferno Canto III marks the beginning of Dante and Virgil’s journey into Hell proper. This canto focuses on the entrance to Hell and the first group of souls Dante encounters – the souls of those who remained neutral in life. The canto underscores the importance of choice and the consequences of inaction, while also presenting the horrifying landscape and atmosphere of Hell.

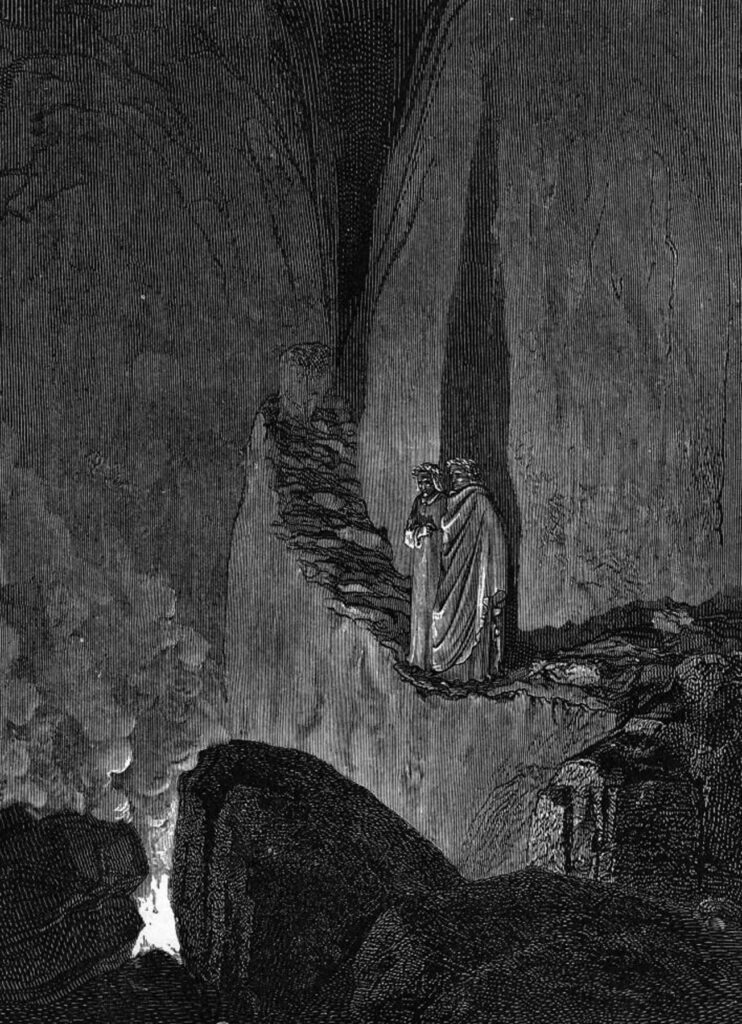

As Dante and Virgil approach the gates of Hell, they read the ominous inscription above the entrance: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” This message serves as a stark reminder of the eternal suffering awaiting those who have been damned. Upon entering, they hear the cries and wailing of countless souls, causing Dante to feel overwhelmed with grief and horror.

In this initial area of Hell, Dante encounters the souls of the indifferent, who never made a stand for good or evil during their lives. These souls are forever condemned to chase after a blank banner while being tormented by swarms of wasps and hornets that sting them. The pus and blood from their wounds are consumed by loathsome worms, emphasizing the degradation and misery that they must endure for their inaction.

Dante and Virgil then approach the river Acheron, which serves as a boundary between the outer region of Hell and the first circle of Hell, Limbo. Here, they find Charon, the mythological ferryman responsible for transporting the souls of the dead across the river to their eternal damnation. When Dante attempts to board Charon’s boat, the ferryman initially refuses, as Dante is still alive. However, Virgil intervenes and reminds Charon that their journey has been sanctioned by divine will, prompting Charon to relent.

As they cross the river, Dante witnesses the souls of the damned wailing and cursing their fate. He is overcome with pity and terror, fainting from the overwhelming experience. This marks the end of Canto III, with Dante’s descent into the deeper circles of Hell yet to come.

In summary, Inferno Canto III serves as the introduction to Hell and its torments. Dante and Virgil enter through the gates and encounter the souls of the indifferent, who are punished for their inaction in life. The canto emphasizes the consequences of the choices made during one’s life and the eternal suffering awaiting those in Hell. As Dante and Virgil cross the river Acheron, Dante is overcome with the horrors of the damned souls, reinforcing the terrifying nature of Hell and setting the stage for the journey through the nine circles of Hell that follow.

Canto IV – The First Circle, Limbo

The Great Poets | Heroes and Heroines | The Philosophers & Other Great Spirits

In Canto IV, the descent was into the First Circle of Hell, known as Limbo. Limbo is a place of sorrow, yet it is not a realm of torment as the circles that follow. It is inhabited by the souls of the unbaptized and virtuous pagans who, due to their ignorance or lack of Christian faith, are unable to enter Heaven.

As Dante and Virgil enter Limbo, Dante describes the atmosphere as dense and dark, with a mournful air. Dante is struck by a deep sense of melancholy, as the souls within this circle are not subjected to physical torture but are instead weighed down by the pain of eternal separation from God. The only light in Limbo emanates from a mysterious, ever-glowing castle, which symbolizes the knowledge and wisdom of the inhabitants.

Virgil, who himself resides in Limbo, introduces Dante to a group of eminent figures known as the Virtuous Pagans. These illustrious individuals, which include poets, philosophers, and heroes from ancient Greece and Rome, have been granted a relatively dignified afterlife due to their exceptional contributions to humanity. They are, however, still deprived of the ultimate joy of divine presence.

The group of souls includes Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan—four of the greatest poets from antiquity. Dante, overwhelmed by their presence, refers to them as “the light-bringers of the world” and expresses his humility at being considered worthy of their company. Virgil and Dante continue their journey, encountering other notable figures such as the philosophers Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Seneca; the mathematician Euclid; and the physician Hippocrates. Additionally, they meet mythical and historical heroes like Aeneas, Caesar, and Hector.

Dante is moved by the sight of these extraordinary souls and sympathizes with their fate. Virgil, aware of Dante’s compassion, explains that while these individuals led exemplary lives and made significant contributions to human knowledge, they were still unable to attain salvation due to their lack of Christian faith or baptism. This realization underscores the strict theological doctrine of the time, which placed immense importance on adherence to Christianity.

As they proceed, Dante observes a group of souls belonging to the Old Testament, such as Adam, Noah, Moses, and King David. He learns that they were once part of Limbo until Christ’s descent into Hell, known as the Harrowing of Hell, when Christ liberated the souls of the righteous who had been waiting for redemption.

With this new understanding, Dante’s sympathy towards the virtuous pagans deepens, as he contemplates the harsh reality of their eternal state. As they leave Limbo, Dante is left to ponder the divine justice and the fate of these noble souls who, despite their virtues, are eternally barred from the heavenly realms. This thought-provoking canto raises profound questions about the nature of divine justice, morality, and the role of human achievement in the context of eternal salvation.

Canto V – The Second Circle, Lust (Minos)

The Carnal Sinners | Virgil Names the Sinners | Paolo and Francesca

Inferno Canto V is a journey through the second circle of Hell. This circle is reserved for those who succumbed to lust in their earthly lives, condemned to be eternally buffeted by violent storms, symbolizing the uncontrollable passions that led them astray. The Canto explores themes of love, desire, sin, and divine punishment as Dante encounters and empathizes with the souls of the damned.

As Dante and Virgil descend from Limbo into the second circle, they are met by Minos, the mythological king of Crete, who now serves as the infernal judge. Minos assigns souls to their appropriate circles of Hell by wrapping his tail around his body a corresponding number of times. Despite Minos’ warning that Dante does not belong in this realm, Virgil asserts his divine mandate to guide Dante, and the pair proceed.

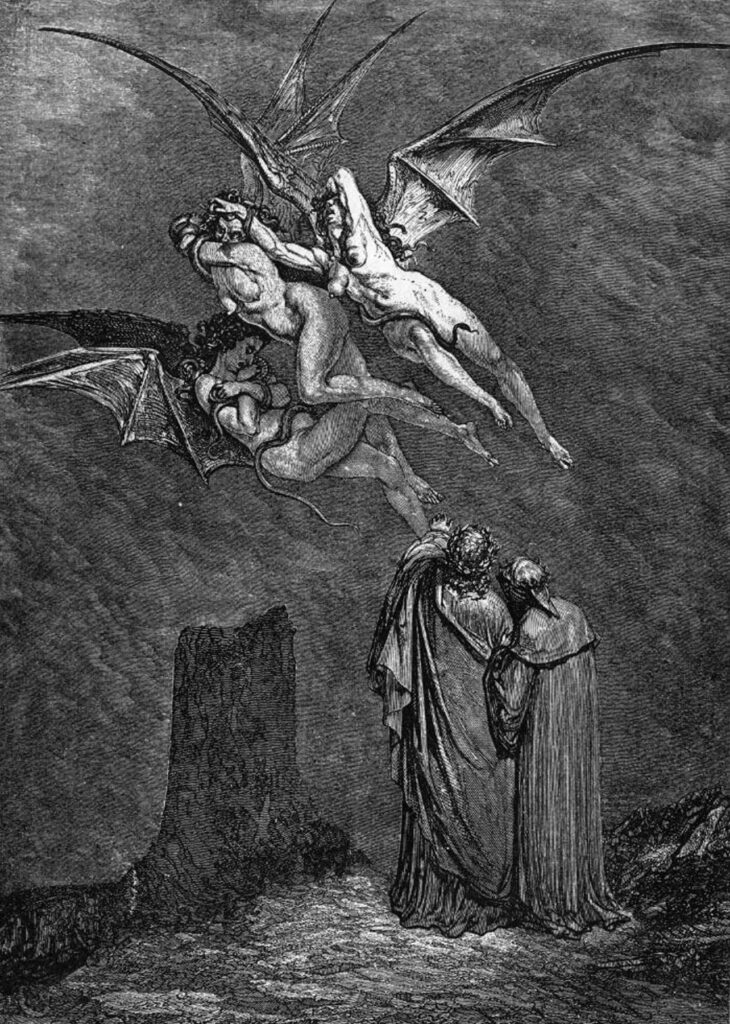

Entering the second circle, Dante witnesses a multitude of tormented souls swept away by violent winds. Virgil explains that these are the souls of the lustful, who allowed their desires to overcome their reason. Among these souls are notable figures from history and mythology, including Cleopatra, Helen of Troy, Paris, and Tristan.

As Dante observes these sinners, he is particularly struck by two intertwined souls, Francesca da Rimini and her lover, Paolo Malatesta. Dante feels a deep sympathy for Francesca and calls out to her, asking her to share her story. Francesca recounts how she and Paolo, the brother of her husband Gianciotto, fell in love while reading the romantic tale of Lancelot and Guinevere. They succumbed to their passions, and when Gianciotto discovered their affair, he murdered them both.

Francesca’s tale highlights the power of love, which she claims even the most virtuous cannot resist. She is resigned to her fate, regretting only that her love for Paolo led to their damnation. Dante, deeply moved by Francesca’s story, is overcome with grief and faints. The Canto concludes with Dante’s unconscious body lying on the ground, his soul weighed down by the tragic consequences of love and desire.

Inferno Canto V is an important part of Dante’s journey, as it serves as his first direct encounter with sinners and their punishments in Hell. It elicits strong emotions from the protagonist, illustrating his vulnerability and human empathy. The Canto also provides a glimpse into the complex, interwoven nature of love and sin, setting the stage for further exploration of these themes throughout the “Divine Comedy.”

Canto VI – The Third Circle, Gluttony (Cerberus)

Ciacco, the Glutton | Ciacco’s Prophecy | Virgil Speaks on The Day of Judgement

Inferno Canto VI presents the third circle of Hell, where the gluttonous are punished. The Canto commences with Dante awakening from a faint, following the events of the previous Canto, in which he witnessed the torments of the lustful. He is accompanied by the ancient Roman poet Virgil, who serves as his guide throughout their journey in Hell.

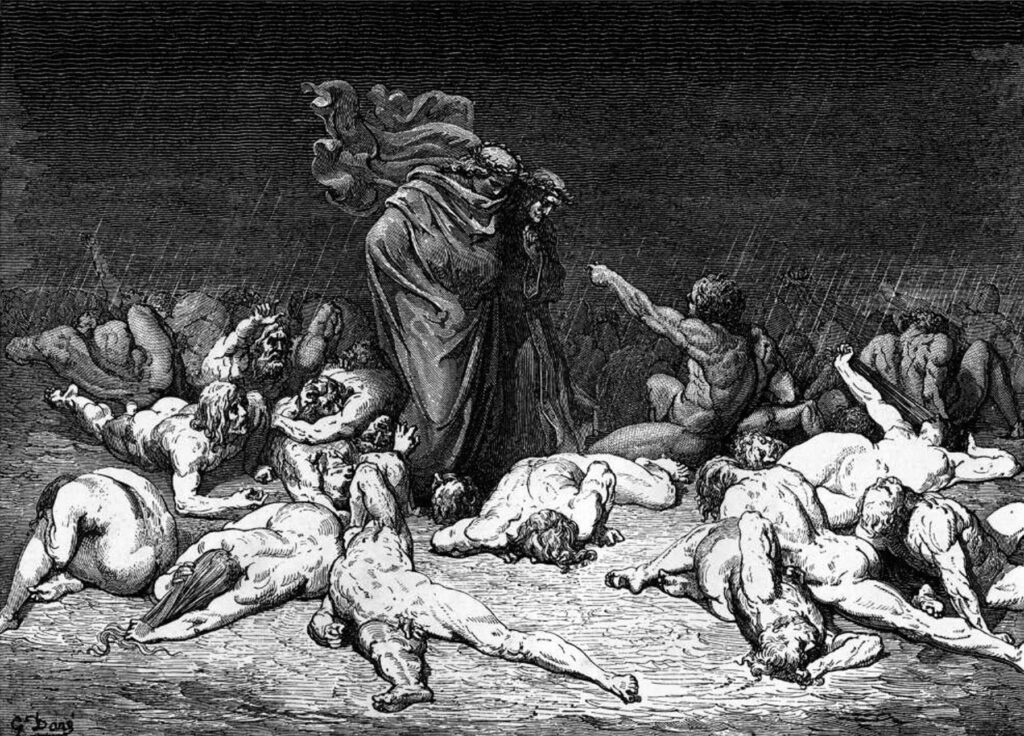

As they proceed, Dante describes the cold, heavy, and incessant rain that pours down in this circle, accompanied by hail, snow, and filthy water. The atmosphere is one of darkness and despair. The damned souls lie in the putrid sludge, experiencing extreme discomfort, and are guarded by Cerberus, the monstrous three-headed dog from Greek mythology. Cerberus viciously claws and bites at the souls, symbolizing the self-destructive nature of their sin – gluttony.

Virgil, in an attempt to pacify Cerberus, picks up a handful of mud and throws it into the beast’s mouths, allowing the poets to pass safely. As they walk through the disgusting mire, Dante notices that the spirits are unrecognizable due to their disfigurement from the punishment. He soon encounters the soul of Ciacco, a former acquaintance from Florence, who is now a gluttonous sinner. Despite his miserable state, Ciacco recognizes Dante and requests to speak with him.

Ciacco prophesies about the political turmoil in Florence, describing the conflict between the two rival factions, the White Guelphs and the Black Guelphs. He foretells that the White Guelphs, Dante’s own faction, will be exiled from the city. This prediction aligns with the historical reality, as Dante was indeed exiled from Florence in 1302. Ciacco also laments the moral decay of Florence, attributing the city’s decline to the sins of its inhabitants.

Dante, deeply affected by Ciacco’s words, inquires about the fate of other prominent Florentines. Ciacco explains that many of them are suffering in lower circles of Hell, enduring even worse punishments for their sins. He then requests Dante to remember his name and plight when he returns to the world of the living. As the conversation concludes, Ciacco returns to the muddy slush, disappearing from sight.

Distressed by the revelation of his homeland’s future, Dante asks Virgil about the damned souls’ capacity to foresee future events. Virgil explains that the spirits have no knowledge of the present but can glimpse the future, albeit imperfectly. However, once Judgment Day arrives, their ability to foresee the future will cease.

As the Canto draws to a close, Virgil leads Dante to the next circle of Hell, where they will continue their journey and witness the punishments of other sinners.

Canto VII – The Fourth Circle, Avarice (Plutus)

The Prodigal Churchment | Virgil’s Views About Fortune | The Styx

Canto VII is a witness to the punishments of two types of sinners: the avaricious and the prodigal, and the wrathful and sullen.

The Canto begins with Virgil and Dante at the edge of the Fourth Circle of Hell, where they encounter Plutus, the god of wealth in classical mythology, who tries to block their path with a nonsensical incantation. Virgil rebukes Plutus, reminding him of their divine mission, and the beast collapses in fear, allowing them to continue.

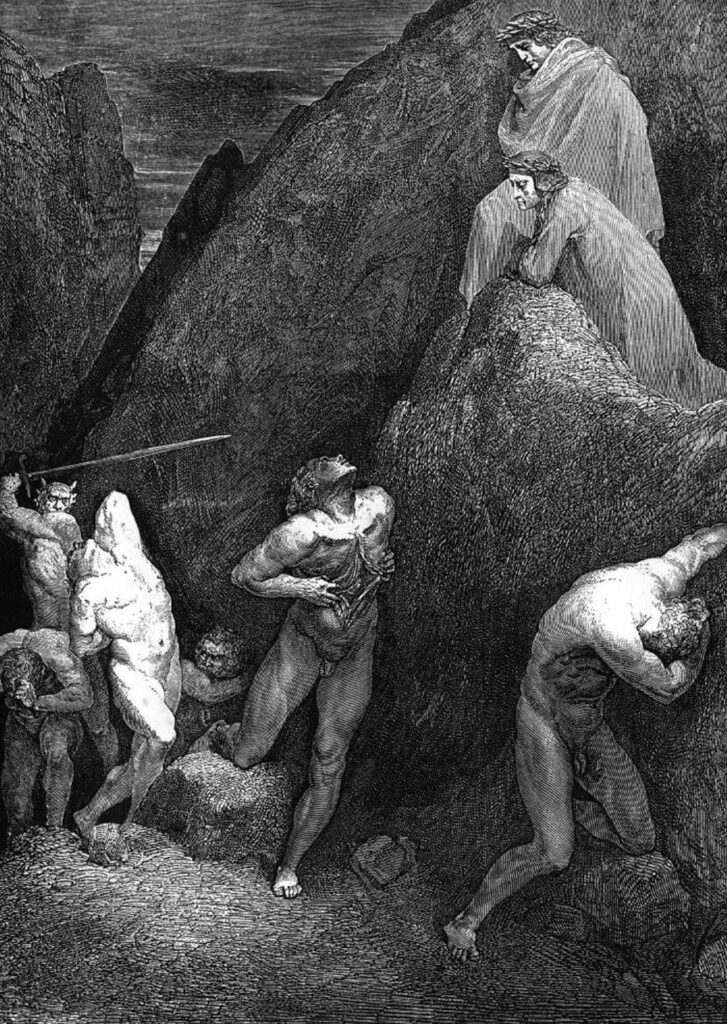

The Fourth Circle houses the Avaricious and the Prodigal, those who either hoarded possessions or squandered wealth. These sinners are condemned to eternally joust with massive weights which they push with their chests. The hoarders and wasters cannot stop clashing into one another, demonstrating the senseless conflict and the futile nature of their respective sins.

Virgil explains to Dante that Fortune, a divine entity, controls the distribution of earthly goods according to a grand divine plan that humans cannot comprehend. She shifts wealth between nations without care for human pleas or prayers, maintaining a balance. Dante then asks about the identities of the sinners, but Virgil asserts that their mortal identities are insignificant as they are now unrecognizable and their fame has faded on Earth.

The pair then moves towards the Fifth Circle, where the river Styx is located. This is the place for the Wrathful, who are seen fighting each other on the surface of the muddy waters, and the Sullen, who gurgle beneath the water’s surface. These sinners are those who expressed their anger violently or repressed it in life, resulting in their respective punishments.

While still in the boat with Phlegyas, a figure from classical mythology who represents sudden wrath, Dante recognizes one of the wrathful souls as Filippo Argenti, a former Florentine citizen known for his anger and violent nature. Dante shows no sympathy for him, and Argenti is torn apart by the other wrathful souls. This marks a moment of moral confusion for Dante as he indulges in the very sin he sees punished.

After a brief altercation with Filippo, Dante and Virgil are surprised by a sudden trembling of the Earth. The Canto ends with Virgil reassuring Dante that he will soon understand the reason behind the earthquake, setting the stage for their approach to the city of Dis in the subsequent Canto.

Canto VII explores the broader theme of divine justice. Here, Dante suggests that the human understanding of wealth and anger is inherently flawed, and that divine justice serves as a corrective to these misunderstandings. The punishments witnessed are fitting ‘contrapasso’ – they are the distorted reflections of the sins committed in life.

Canto VIII, The Firth Circle, Wrath (Phlegyas)

Filippo Argenti | View of the City of Dis | Fallen Angels Obstruct Dante

As Canto VIII begins, Dante and Virgil have reached the banks of the Styx, the fifth circle of Hell, where the wrathful and sullen sinners are punished. They’re waiting for the ferryman, Phlegyas, to take them across the river.

Dante first perceives, in the dim light, some bubbles breaking on the surface of the marsh. Virgil explains that these are the sullen, those who sulked in life without joy, now submerged beneath the mire and mud of the Styx. Their groans echo hollowly from beneath the water’s surface.

Suddenly, the boatman Phlegyas, a figure from classical mythology known for his quick temper, arrives. He chastises Dante for still being alive but is silenced by Virgil, who assures him that their journey is willed from above. Phlegyas allows them to board his skiff, albeit begrudgingly. As they cross the Styx, the marsh appears alive with the wrathful who are perpetually fighting each other.

During the crossing, a muddy soul emerges from the Styx, recognizing Dante. This sinner is Filippo Argenti, a former political enemy of Dante from Florence. Dante responds with contempt, refusing to acknowledge Argenti and instead condemning him to his deserved torment. Dante’s intense reaction shows his disgust and anger for those who have betrayed Florence, and this is one of the rare moments in the Inferno where Dante shows no sympathy for a damned soul. In fact, he openly enjoys the punishment Argenti is receiving.

Just as the episode with Filippo Argenti ends, a commotion begins on the far side of the river. Dante sees many fiery lights moving in the distance, and the entire city of Dis, the great capital of Hell, comes into view. Dante questions Virgil about the lights, and Virgil explains that they belong to emissaries from the city of Dis, who are coming to oppose Dante’s further journey into the deeper parts of Hell.

Canto VIII ends in suspense as Dante and Virgil approach the city and prepare to face the challenges that await them. Dante expresses his fear and doubts about their journey to Virgil, a theme that continues in the next Canto, as Dante’s journey into the heart of Hell is challenged by its most powerful denizens.

Throughout Canto VIII, Dante presents a vision of Hell that is not just physically tormenting, but also psychologically punishing. The wrathful and sullen are not merely suffering physical discomfort but are subjected to an existence that reflects the fruitless anger and joyless despair that characterized their lives. Similarly, Dante’s encounter with Filippo Argenti reflects the lasting impact of earthly conflict, while the looming confrontation at the gates of Dis indicates the spiritual resistance to repentance and divine justice.

Canto IX – The City of Dis

The Furies and Medusa | Messenger from Heaven | Entry to Dis

This Canto begins with Dante and Virgil standing outside the gates of the city of Dis, also known as the City of Hell. This location signifies the entrance to Lower Hell, which houses the deeper, more sinful circles. Dante and Virgil find their path blocked by fallen angels who refuse to let them pass.

As they approach the gates, Dante is suddenly overcome with fear, an emotion that recurs throughout the Canto. His apprehension stems from an awareness of the gravity of the situation and his realization that this journey is unlike any other, and its implications are life-altering. Virgil, usually the confident guide, also shows signs of anxiety and unease, which further exacerbates Dante’s fear.

Virgil tries to negotiate with the fallen angels for passage, but to no avail. Dante’s spirits plummet when he sees Virgil’s attempts to reason with the angels fail. It’s a moment of crisis in their journey, the first time that Virgil’s rhetorical skills have failed them. Dante even fears abandonment by Virgil, who for him is not only a guide but also a moral compass and a source of comfort. This uncertainty adds a psychological complexity to the narrative.

As Dante despairs, Virgil reassures him that a divine messenger from Heaven is on the way to intervene. These moments of waiting are tense and filled with anticipation. Dante’s fear subsides somewhat, but the atmosphere remains heavy with trepidation.

Indeed, a divine messenger eventually appears, radiating an intense light, symbolizing divine intervention and goodness. This messenger reproaches the rebellious angels and effortlessly opens the gates of the city that they had been guarding so fiercely. The ease with which the messenger accomplishes this task emphasizes the absolute power of divine authority.

With the path cleared, Dante and Virgil enter the city. As they pass through, they see tombs engulfed in flames. These tombs belong to the heretics, punished in the sixth circle of Hell for their denial of immortality. This sight leaves a deep impression on Dante and sets the tone for their journey further into Hell.

The Canto ends on a cliffhanger as Dante faints from the overpowering fumes emanating from the tombs. This ends the ninth Canto of Dante’s Inferno, highlighting a journey fraught with fear, tension, and anticipation.

In summary, Canto IX portrays a critical turning point in Dante’s journey through Hell, with the protagonist and his guide encountering significant obstacles that are overcome through divine intervention. This Canto explores themes of fear, divine power, rebellion, and the eternal consequences of disbelief.

Canto X – The Sixth Circle, Heresy

Cavalcante Cavalcanti | Farinata Prophesies Dante’s Exile | The Prophetic Vision of the Damned

Canto X of Dante’s “Inferno” commences with Dante and Virgil’s entry into the Sixth Circle of Hell, the realm designated for the punishment of heretics. As Dante observes the structure of this circle, he likens it to the sepulchers found in his home city of Florence, which sets an eerie and grotesque atmosphere.

The Sixth Circle, a vast, gloomy cemetery, is filled with open flaming tombs. The tombs torment the condemned with perpetual fires, symbolizing their heretical views that led them astray during their lives on Earth. Dante inquires as to the identities of those suffering within these fiery sepulchers, to which Virgil responds that the most prominent among them are from Epicurus and his followers, who, in denying the immortality of the soul, committed heresy against Church doctrine.

They come across one open tomb from which a voice emerges, questioning Dante about the state of Florence. This voice belongs to Farinata degli Uberti, a nobleman and former military leader in Florence, who was charged with heresy posthumously. Despite their political differences in life (Farinata was a Ghibelline leader and Dante a Guelph), Farinata treats Dante with a certain respect and shows great interest in the political state of their city, demonstrating his continued attachment to his earthly life.

Their conversation is interrupted by another damned soul, Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti, father of Dante’s dear friend and poet, Guido Cavalcanti. Cavalcante rises from the same tomb as Farinata and is anguished to think that his son might also be dead, based on Dante’s lack of mention of Guido. Dante starts to reassure Cavalcante that his son is alive, but before he can finish his sentence, Cavalcante, already too despairing, sinks back into his tomb.

Farinata, ignoring this exchange, resumes their conversation about Florence. Dante probes him about his knowledge of the future, as the souls in Hell are said to possess. Farinata explains that while they can see the future, they are unable to see the present, creating an unusual perspective of time.

The canto ends with Farinata predicting Dante’s difficult journey back to Florence. The two poets then continue on their journey, leaving the fiery graves behind them. This canto is marked by political commentary, theological discourse, and explorations of familial relationships and personal legacies, all set in the grim landscape of the Sixth Circle of Hell.

Canto XI – The Lower and Upper Circles of Hell

The Lower Circles | The Upper Circles | Virgil Explains Ursury

Canto XI is a pivotal section of this narrative where Dante and his guide, Virgil, pause at the edge of the Seventh Circle to acclimate themselves to the horrendous stench rising from the pit below. This canto provides a detailed explanation of the sinners’ classification and punishments, and the architecture of Hell itself, according to the guiding philosophy of the epic.

The canto starts with Dante and Virgil standing near the broken rocks of the Seventh Circle’s edge. Here, the stench from the pit of Hell, which contains the sinners of the lower Circles, is so overwhelming that they cannot proceed further without becoming accustomed to it. This stench emanates from the bodies of the sinners below who are punished for their sins of violence.

During this pause, Dante takes the opportunity to ask Virgil about the structure of Hell and the divisions of sins according to their severity. He mentions that he didn’t see any punishment for the avaricious or the prodigal in the upper Circles, prompting Virgil to explain the layout and categorization of sins in Hell, according to the philosophy of Aristotle.

Virgil explains that all sins stem from love – either excessive love, deficient love, or misdirected love. He describes the three divisions of Hell in accordance with this theory. The first is “Incontinence”, which includes lust, gluttony, and greed – sins that involve not being able to control one’s desires. The second is “Violence”, which includes sins against others, oneself, and God or nature. The third is “Fraud” or “Malice”, which includes sins of betrayal and deceit.

It’s explained that the sins of incontinence, though grave, are less serious than the sins of violence, and the sins of violence are less serious than the sins of fraud. This hierarchy stems from the understanding that sins of incontinence are more human in nature and less malicious, while sins of violence and fraud involve malice and a direct, conscious intent to do harm.

Virgil also explains the subdivisions within these divisions, describing specific punishments for each kind of sin. He tells Dante about the different circles of Hell that are reserved for the sins of violence, which include violence against neighbors, oneself, and God, nature, and art.

Inferno Canto XI also mentions the sinners who are punished outside of Hell – the Virtuous Pagans and the Unbaptized, who, though not sinful, did not know Christ. It also alludes to the structure of Purgatory and its divisions based on the seven deadly sins.

Lastly, in the shadow of the towering figure of the ancient Theban prophet Tiresias’s daughter, Manto, who wandered the world after her father’s death, Virgil briefly recounts the founding of his native city, Mantua. This provides a rare moment of personal history within the grand theological and moral narrative.

After this detailed discourse, as the duo has become accustomed to the stench, they prepare to descend further into Hell, ending Canto XI.

Overall, this canto serves as an essential exposition of the organization of Hell, explaining Dante’s moral philosophy and laying the foundation for the punishments and torments that are to come in the lower Circles.

Canto XII – The Seventh Circle, Violence I

The First Ring | The Tyrants, Murderers, and Warriors | The Minotaurs

Canto XII begins with Dante and Virgil descending into the seventh circle of Hell. The seventh circle is divided into three rings, which house those who have committed violence against others, against themselves, and against God. Canto XII focuses primarily on the first ring.

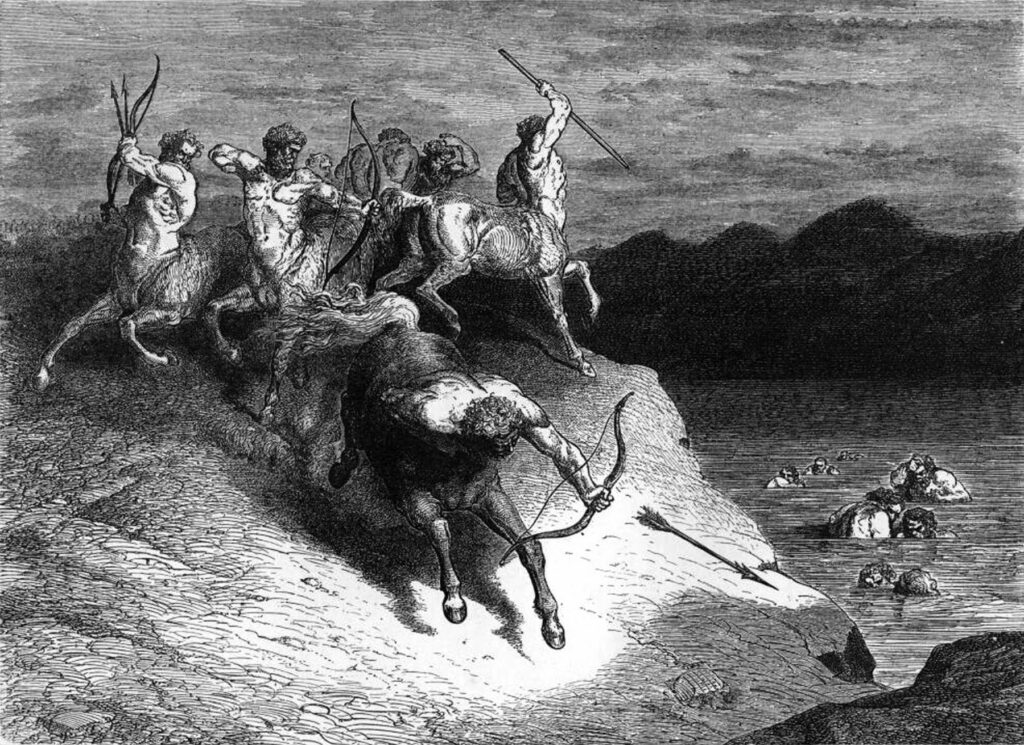

As the two companions approach the edge of the cliff overlooking this new circle, they encounter the monstrous Minotaur. The Minotaur, a creature from Greek mythology, is the guardian of this ring. Dante’s guide, Virgil, distracts the Minotaur with a clever verbal taunt, allowing the pair to sneak past him and safely down the cliff.

The cliff they descend is a landslide caused by the great earthquake that occurred when Christ died, a direct reference to the biblical account of Christ’s crucifixion. This is a recurring theme in Dante’s journey, where historical and biblical events have physically shaped the landscape of Hell.

Once at the bottom, they find the river of boiling blood, the Phlegethon, a horrific scene depicting divine retribution for violence. The sinners immersed in the river are those who have been violent against their neighbors. The level at which each sinner is submerged in the river corresponds to the degree of violence they committed in life. For instance, Attila the Hun, known as the “Scourge of God,” is completely submerged, while others less notorious might only be submerged to their waist or ankles.

This river is patrolled by Centaurs, creatures that are half man, half horse, who shoot arrows at any sinner attempting to rise higher out of the boiling blood than their sins allow. Chiron, the chief Centaur, recognizes Virgil and Dante as living beings, an anomaly in Hell. Virgil explains their journey, after which Chiron assigns another Centaur, Nessus, to guide them across the river.

While they are crossing the river, Nessus points out several notable sinners, including Alexander the Great and Dionysius I of Syracuse, notorious for their violent rule. Also pointed out is Guy de Montfort, responsible for a politically motivated murder in the church.

Once they reach the other side of the river, Nessus leaves Dante and Virgil to continue their journey into the deeper parts of Hell. The canto ends on an ominous note, with Dante and Virgil walking away alone into the dense, dark forest that marks the beginning of the second ring of the seventh circle, where those who were violent against themselves, the suicides, are punished.

In Canto XII, Dante emphasizes the concept of contrapasso, or the law of divine justice, by ensuring the punishment fits the sin. The violent sinners eternally endure the violence they inflicted in life, submerged in boiling blood. This also demonstrates Dante’s belief that violence against others is one of the worst sins a person can commit. The inclusion of notable figures from history and mythology further shows the indiscriminate nature of divine judgment. Dante’s Inferno, and especially this canto, acts as a moral lesson and a reflection on divine justice and the nature of sin and punishment.

Canto XIII – The Seventh Circle, Violence II

The Second Ring | The Suicides | The Harpies

In Canto XIII of Dante and Virgil descend into the second ring of the seventh circle where those who committed violence against themselves (the suicides) are punished.

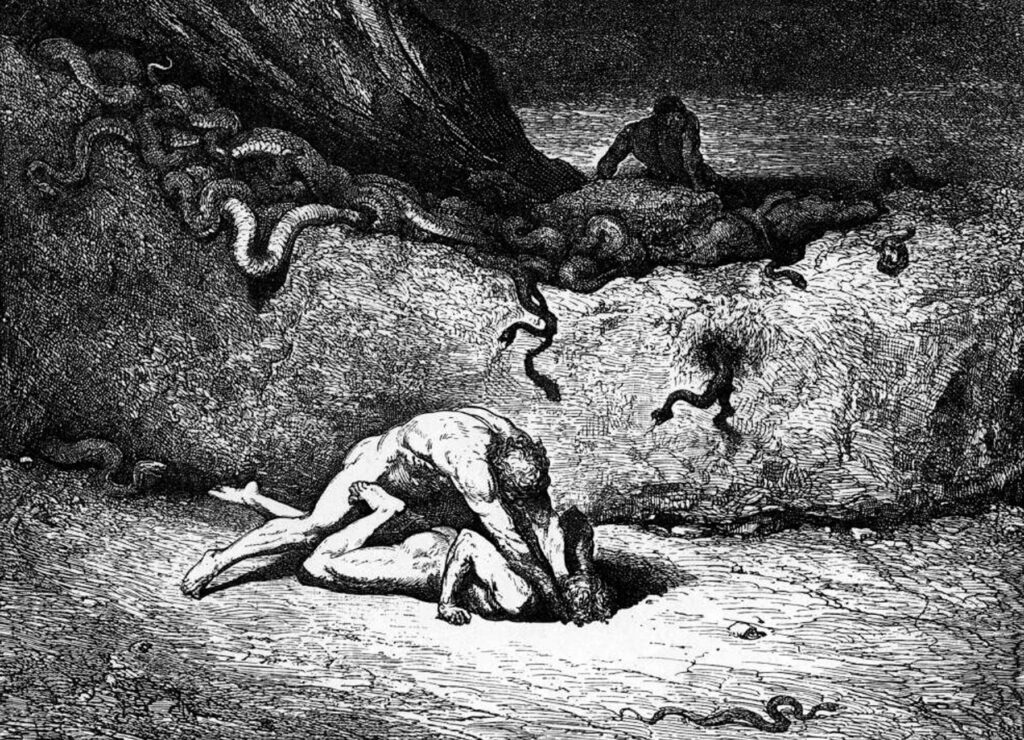

The Canto begins with the poets entering a dark and twisted forest. Unlike any earthly woods, the trees in this grove are black, gnarled, and devoid of green foliage. Instead of birdsong, the air is filled with wailing and shrieks of despair. Dante is surprised to find no wildlife, only strange, harpy-like creatures perched in the trees. These creatures, the harpies, feed on the trees and cause them pain, a fitting symbol of self-destruction that resonates with the sin of suicide.

Curious and confused, Dante breaks off a twig from one of the trees. Instead of sap, blood oozes out, and the tree cries out in pain. The tree is actually the soul of Pier delle Vigne, once a trusted advisor to Emperor Frederick II. Pier shares his tragic story, explaining how envy led to his false accusation of treason, after which he fell into despair and took his own life. In Hell, he’s been transformed into a tree and is constantly tormented by the harpies.

Dante, deeply moved by Pier’s tale, listens as he explains the punishment of suicides in Hell. Their souls fall here as seeds, sprouting into trees. They can never retrieve their bodies as these are rejected by the earth, and they must endure this torment for eternity, unable to express their pain unless their branches are broken, releasing their words in the form of bloody sap.

Shortly after, Dante and Virgil encounter another pair of souls: Lano da Siena and Jacomo da Sant’Andrea, punished in this ring for squandering their wealth. They are not transformed into trees but are chased and torn to pieces by ferocious dogs over and over again. This is a fitting punishment for their reckless disregard for their material possessions in life, which Dante equates to a form of self-violence.

Finally, Dante and Virgil leave this gruesome forest. The Canto ends as Dante follows Virgil, reflecting on the cruel fate of the souls they encountered. This journey deepens Dante’s understanding of sin and its repercussions, fueling his sympathy for the damned and igniting his wrath against the sin that led them there.

Canto XIII presents a vivid and harrowing depiction of self-destruction, offering a damning commentary on despair and reckless waste. It interrogates the morality of suicide and squandering, inviting the reader to ponder the consequences of violence against oneself, either through bodily harm or through reckless misuse of one’s resources.

Canto XIV – The Seventh Circle, Violence III

The Third Ring | The Blasphemers | The Burning Desert

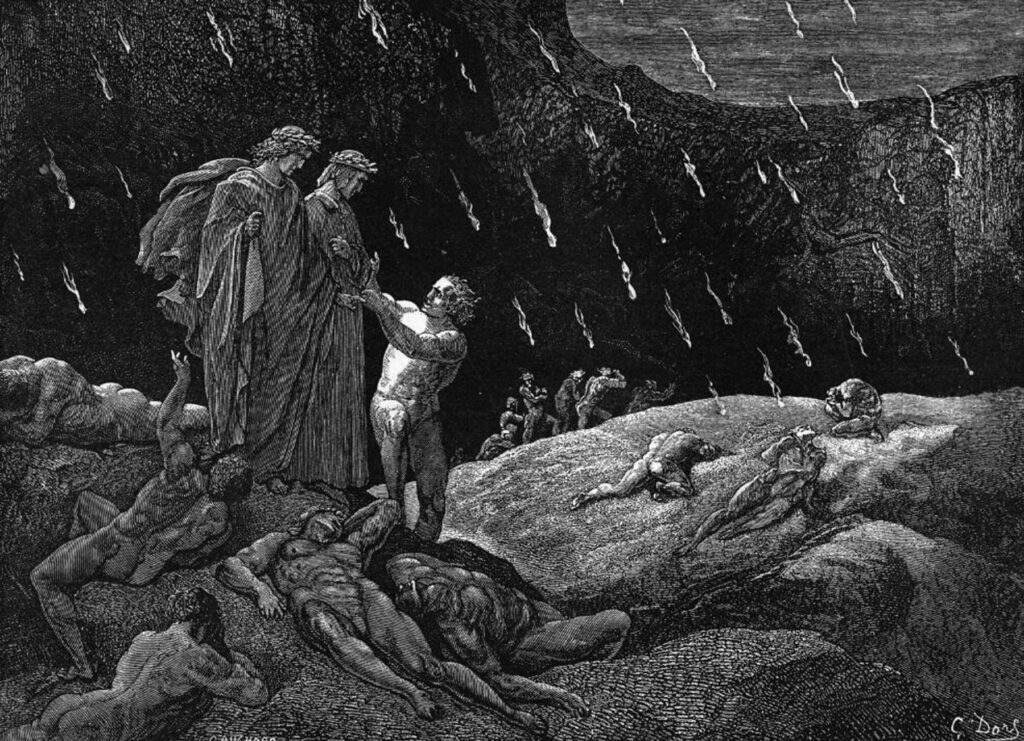

The Canto begins with Dante and Virgil on the edge of a dry, desert-like plane. Dante hears Virgil, his guide, encouraging him to witness the consequences of sin around him. The plane is fiery and hot, similar to the climate of the Sahara. The soil is burning and there are flakes of fire, similar to snowflakes, falling from the sky. These flames are burning the souls of the sinners who wander aimlessly, naked, in this blazing desert.

Virgil tells Dante that the desert is the home of the blasphemers (those who have shown contempt or lack of reverence for God), the sodomites (those who have committed sexual acts against nature), and the usurers (those who have gained wealth through interest and extortion). All three groups are considered to have committed violence against God, either directly or indirectly.

One particular sinner, Capaneus, is lying supine on the burning ground, scorched by the continuous rain of fire. He was one of the seven kings who besieged Thebes and he is eternally punished for his blasphemy against Jupiter (Zeus). Capaneus’ defiance towards God remains unchanged even in Hell. He continues to curse the deity, which only increases his suffering. Dante reflects on the theme of divine justice, noting that the pride and defiance of Capaneus only make his punishment more severe.

Following their encounter with Capaneus, Virgil explains to Dante the divine structure of the universe. He describes how the universe, the earth, and the underworld are linked by a common center of gravity. This explanation includes the mythological story of the old world, the ancient Greek conception of the earth and the sea, and the fall of Lucifer.

Virgil then guides Dante to the edge of the burning desert, towards the third ring of the Seventh Circle, which is a river of boiling blood. To avoid the burning sand and the rain of fire, they walk along a narrow path. Virgil also reveals that the fiery desert was created by the fall of Lucifer, whose massive displacement of land created the underworld.

The Canto marks the transition to the next part of the Seventh Circle. Canto XIV is rich with symbolism and allegory, emphasizing the punishments fitting the sins committed, and further demonstrating Dante’s understanding of divine justice.

Canto XV – The Seventh Circle, Violence IV

Dante’s Fate | The Sodomites | The Rain of Fire

Canto XV begins as Dante and Virgil emerge onto the burning sands of the seventh circle of Hell, reserved for those who were violent against nature and the divine order, including the sin of sodomy. This Canto is particularly significant as Dante encounters his teacher, Brunetto Latini, a known figure in Florentine politics and intellectual circles, among the damned.

As they walk along the fiery sands, they are forced to avoid falling flakes of fire, reminiscent of a summer storm, only far more dangerous. Dante compares these flakes to the flames that destroyed the Biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. Dante and Virgil must tread carefully along the sand to avoid the rain of fire.

Suddenly, Dante is recognized by one of the sinners running in the fiery sand, who turns out to be Brunetto Latini. Latini is presented with an aura of reverence and dignity, despite the grotesque nature of his punishment. Seeing him in such a state, Dante is filled with sympathy and respect for his old teacher, demonstrating the humanizing influence of past relationships even in Hell’s ghastly environment.

Latini, for his part, is also pleased to see Dante and inquires about his journey. When he learns of Dante’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and eventually Heaven, guided by divine power, he offers Dante advice and prophecy about his future. He foretells that Dante will face disloyalty and enmity from the Florentines, a prediction that aligns with Dante’s own experiences of political exile from Florence.

Despite the respect Dante has for Latini, he doesn’t mitigate or downplay the nature of his sin. Dante even compares Latini to both the classical hero Achilles, who was willing to accept his fate, and the Greek philosopher Socrates, who chose death over dishonor. It’s worth noting that the encounters between Dante and the damned often serve as moral and ethical inquiries about earthly life, as well as reflections on his own experiences.

The canto ends with Latini asking Dante to remember his treasured work, “Tesoretto,” and then hurrying off to resume his punishment. As he watches his old mentor leave, Dante reflects on the transient nature of earthly fame and achievements.

Canto XV, therefore, presents a mix of emotions and moral considerations for Dante and the readers, exploring themes of fate, justice, respect, and the enduring value (or lack thereof) of intellectual pursuits and achievements. This encounter emphasizes the personal connection between Dante the character and the souls he encounters in Hell, lending a deeper layer of complexity to his journey through the Inferno.

Canto XVI – The Seventh Circle, Violence V

The Third Ring | The Sodomites | The Monster Geryon

This circle is divided into three rings, and in Canto XVI, they are moving through the third ring, the Violent Against God (the blasphemers), Nature, and Art (the sodomites). Here’s a detailed summary:

At the beginning of Canto XVI, Dante and Virgil find themselves on the edge of a great waterfall, which descends into the eighth circle of Hell. Dante uses the image of the waterfall to illustrate the physical descent of the river Phlegethon. Dante takes a cord from around his waist and drops it into the abyss at Virgil’s instruction, although the reason for doing so is not immediately apparent.

As they prepare to continue their descent, Dante is approached by a group of three shades who recognize him as a fellow countryman. These spirits, who were prominent citizens and military men in Florence during their earthly lives, are now damned to the third ring of the Seventh Circle for the sin of sodomy. They are Jacopo Rusticucci, Guido Guerra, and Tegghiaio Aldobrandi. Each one of these spirits is eager to hear news about their beloved city, Florence, from Dante, who is a contemporary Florentine.

During their conversation, Dante addresses the issue of fame and honor, observing that those who are esteemed on Earth might be suffering in Hell, and those suffering on Earth may be enjoying the highest blessings in the afterlife. This reflection presents a stark contrast to the conventional medieval notion of fame and glory.

Dante empathizes with these spirits as they discuss the misfortunes and moral decay of Florence. The spirits offer their regret and dismay over the current state of the city and its political and moral degradation. Dante’s encounter with these damned spirits is tinged with an unusual degree of compassion and camaraderie, given their shared Florentine heritage.

In a demonstration of pity and respect, Dante promises to keep their names alive on Earth. This not only underscores the importance of remembrance and legacy but also highlights Dante’s ability to command the narrative of those he meets in Hell.

While they’re speaking, the spirits run continuously to avoid being scorched by the burning sand, further emphasizing the restless torment they endure for their sins.

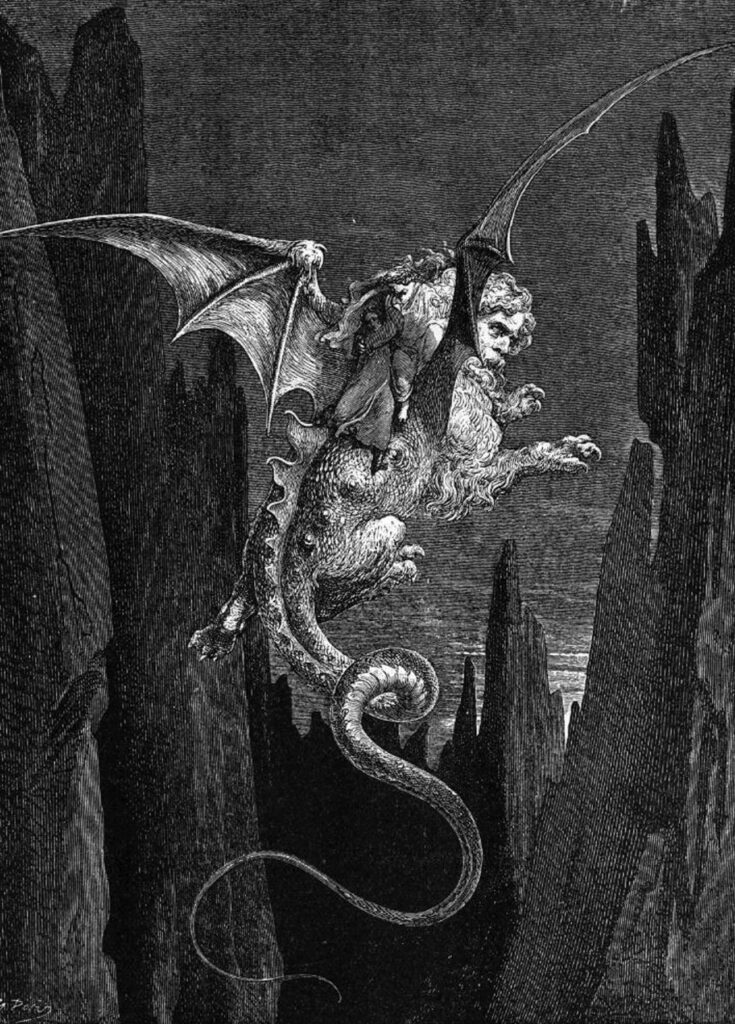

As they conclude their conversation, Virgil praises Dante for his emotional depth and ability to empathize. However, the time has come to move on, and Virgil informs Dante of their path ahead. They’re to be carried downward by a monstrous creature, Geryon, a symbol of Fraud, whose presence suggests their forthcoming journey into the circle of the fraudulent and malicious.

Intriguingly, Canto XVI ends with a cliffhanger, as Dante and Virgil are about to climb onto the monstrous Geryon and descend into the Eighth Circle of Hell, the realm of the fraudulent. The reader is left in suspense, awaiting the duo’s further descent into the infernal depths.

Throughout Canto XVI, Dante further explores the themes of societal decay, the ephemeral nature of earthly fame and glory, and the personal tragedy of damnation. His interaction with the spirits of his fellow Florentines offers a poignant commentary on the state of Florence and humanity’s capacity for self-destruction.

Canto XVII – The Eighth Circle, Fraud

Dante’s Fear | The Usurers | Malebolge

Canto XVII is set in the Eighth Circle of Hell, the Malebolge, dedicated to those guilty of fraud. This canto marks a transitional phase in Dante’s journey and is unique in its vivid imagery and poignant depiction of the sinners and their punishments.

At the beginning of Canto XVII, we find Dante and his guide Virgil on the burning sandy bank where the sodomites reside, having just left his old teacher Brunetto Latini in Canto XV and the usurers in Canto XVI. Dante and Virgil are approached by three sinners from Florence whom Dante recognizes. They are seen running through the flames for eternity, their punishment for their sodomy.

The duo then moves on towards the next chasm, where the usurers, those who lent money at excessive interest rates, are punished. Their hands are eternally ablaze, symbolizing the destructive potential of their greed. As they approach the edge of this chasm, Virgil instructs Dante to unfasten a cord he’s been wearing around his waist. Dante does so and Virgil casts it into the abyss. The reason for this action isn’t immediately apparent.

A unique and monstrous creature emerges – Geryon, the Monster of Fraud. In Dante’s allegory, Geryon represents fraudulent dealings. He is depicted as a terrifying beast with the face of an innocent man, the paws of a lion, a poisonous tail of a scorpion, and a body covered in the markings of a reptile. Virgil, aware that they must use Geryon to descend to the next circle, leaves Dante to talk to the creature.

While Virgil negotiates their passage, Dante is directed by his guide to observe the usurers further. Each usurer, Dante notices, has a purse around his neck, and on each purse is a heraldic device. These symbols indicate the family identity of each sinner, all of whom are so consumed by their greed that they have lost their individual identities. This observation by Dante demonstrates his scorn for the practice of usury, which he views as a perversion of nature and art, a theme that recurs throughout the Divine Comedy.

After the observations, Virgil returns, successful in his negotiation. He instructs Dante to mount Geryon, who functions as an infernal vehicle. Dante does as he is told, but not without fear. Virgil reassures him and joins him on Geryon’s back. After this, Geryon takes off from the cliff and spirals into the terrifying abyss of the Eighth Circle, embodying a deceitful flight. Dante compares the descent to a falcon returning to its handler.

The canto concludes with a terrifying yet intriguing flight into the next circle. Dante’s gaze is fixed below, where he can see the sinners of the Tenth Pouch of the Eighth Circle, the falsifiers, who will be the subject of his exploration in the upcoming cantos. Dante’s fear and anticipation set the stage for the forthcoming scenes of the Inferno. The canto is a showcase of Dante’s brilliant imaginative prowess and his ability to weave together elements of fear, anticipation, and moral critique.

Canto XVIII – The Eighth Circle, Seduction

The First & Second Chasms | The Pimps and Seducers | The Flatterers

At the start of Canto XVIII, Dante and Virgil are standing on the edge of the abyss that leads to the eighth circle of Hell, often referred to as Malebolge, which translates from Italian as “evil ditches.” This circle is designed like an amphitheater and is divided into ten concentric ditches or trenches, each separated by a stone bridge, and each one punishing a different type of fraud.

The first ditch houses the panderers (pimps) and the seducers, who are being driven by demons with whips. Dante recognizes one of the sinners as Venedico Caccianemico, a Guelph from Bologna, who sold his own sister to the Marquis d’Este. Venedico tries to justify his actions, but Dante doesn’t listen and lets him continue to be whipped. Another sinner, Jason of the Argonauts, is also identified here. He deceived and abandoned several women, including Hypsipyle and Medea, during his life.

Next, Dante and Virgil come across the second ditch. This is the place where those guilty of flattery are punished. They are immersed in a river of human excrement, which symbolizes the false words they used in their earthly life. Dante recognizes a flatterer, Thaïs, a woman of ancient history, who flattered her lover excessively.

Throughout the journey, Virgil explains the divine justice behind each punishment. The sinners, during their lifetime, treated others as less than human. Now, in Hell, they are reduced to an inhuman state. For Dante, these graphic and severe punishments are not intended to incite horror, but to demonstrate the consequences of human choices that reject divine love and moral goodness.

While crossing the bridge to the third bolgia, Virgil also teaches Dante about Fortune, a divine entity, who maintains a balance in worldly goods, despite humans blaming her for their own failings.

The canto ends with Dante preparing to describe the next ditch, home to those who committed simony, a sin that involves selling ecclesiastical pardons, offices, or roles. Here, Dante gives a brief glimpse of Pope Nicholas III, who mistook Dante for Boniface VIII, his successor. This glimpse foreshadows the biting criticism of the Church that Dante will present in the next Canto.

In Canto XVIII of “Inferno,” Dante continues his moral investigation and critique of human failings. The vivid images and raw scenes force readers to contemplate the relationship between actions in life and their consequences in the afterlife.

Canto XIX – The Eighth Circle, Simony

The Third Chasm | The Simoniacs | The Sellers of Pardons

It’s in this canto that Dante and his guide, the ancient Roman poet Virgil, explore the fourth pouch of the Eighth Circle of Hell, which is home to the simoniacs — people who have committed simony, or the buying and selling of ecclesiastical pardons, offices, or indulgences.

The canto begins with Dante’s scornful address to the Simoniacs, who have turned a sacred office into a marketplace. He compares them to Simon Magus, a figure from the New Testament who tried to buy the power of the Holy Spirit from the apostles, a story from which the term “simony” derives.

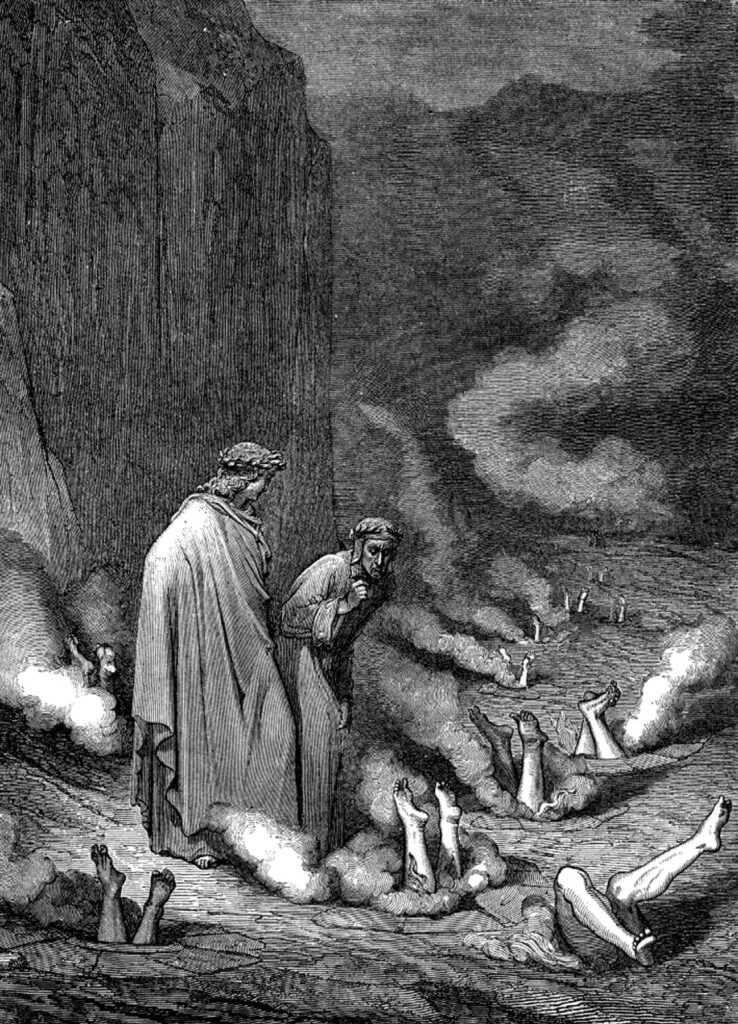

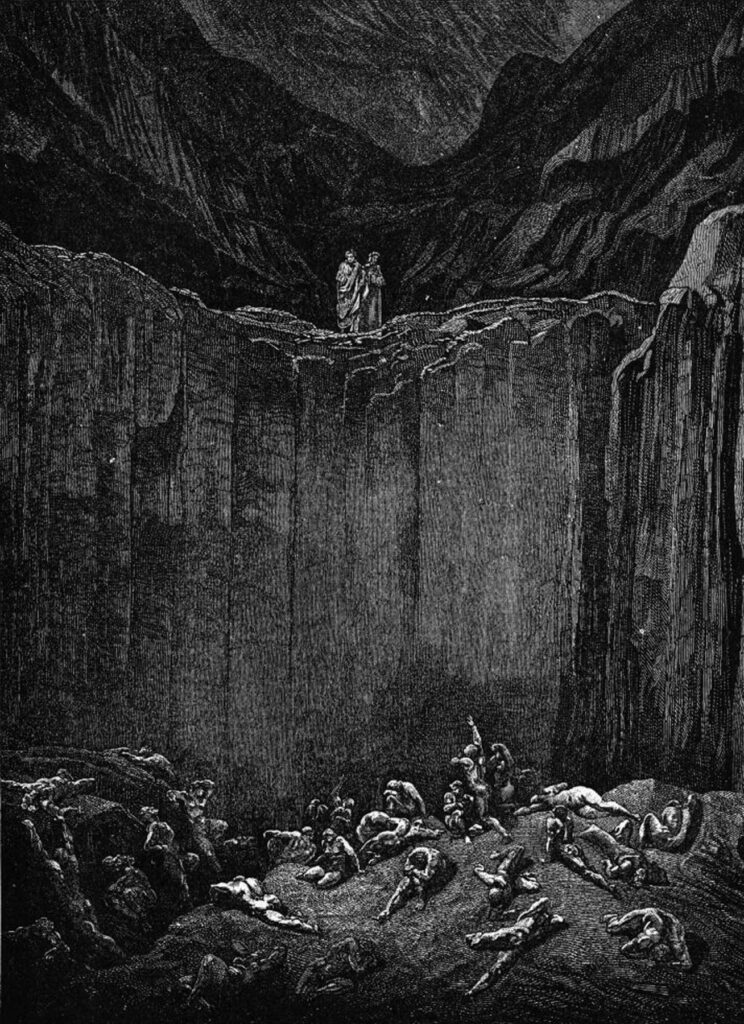

Dante and Virgil see the sinners buried headfirst in rock with their feet sticking out, ablaze with flames. This punishment is a gruesome, ironic inversion of the sacrament of baptism, which symbolizes spiritual rebirth through immersion in water. Instead, these sinners are buried in earth, with the flames symbolizing not the Holy Spirit, but the divine wrath they have earned.

The two travelers come across Pope Nicholas III, who mistakes Dante for his successor, Pope Boniface VIII. Dante uses this opportunity to critique the corruption in the Church, as both popes were accused of simony during their papacies. Nicholas laments his fate and predicts the arrival of Boniface, stating that he too will soon endure the same punishment. He also foretells the coming of a third simoniac pope, Clement V.

During his conversation with Nicholas, Dante voices his disgust at the way the Church’s spiritual authority has been exploited for personal gain, calling it a perversion of its intended purpose. He views this corruption as not just sinful but also as a betrayal of the faith.

When Nicholas finishes his predictions, he returns to his punishment, and Virgil lifts Dante to descend to the fifth pouch. Before they leave, Dante delivers a passionate critique of the corruption and greed that have infected the Church.

Canto XIX is a particularly poignant part of Dante’s journey through Hell as it emphasizes the poet’s fury at the corruption within the Church. His use of real historical figures cements the reality of the sins committed and provides a powerful critique of the individuals involved and the institutions that allowed such transgressions.

Canto XX – The Eighth Circle, Astrology

The Fourth Chasm | The Seers & Sorcerers | The Astrologers, Fortune Tellers

Dante and Virgil have just left the fifth pouch of the Eighth Circle, the Malebolge, where corrupt politicians are punished, and now they arrive at the sixth pouch. Here, Dante employs various literary devices to present a dramatic exploration of the condition of fortune-tellers and diviners, who are damned for their attempts to see the future, a divine prerogative.

Canto XX starts with a strong note of horror, conveyed through Dante’s invocations of Manto, the daughter of Tiresias, a legendary prophet from Thebes. Dante is horrified by the sight he beholds: the souls of fortune-tellers and diviners are grotesquely deformed with their heads twisted backwards on their bodies, a justifiable divine retribution for trying to see too far ahead in their lifetime.

They weep profusely, and their tears fall on their buttocks along the twisted path they walk backwards, as their punishment is to move forward while looking back, signifying a reversed reflection of their sinful lives. Their eyes, once used to predict the future illegally, are blinded by their own tears. In this way, Dante’s depiction offers a harsh critique of those who, in his view, overstep their human boundaries and attempt to usurp divine powers.

During their progression through this canto, Dante recognizes many souls who were known for their prophetic abilities in life, including Amphiaraus, Tiresias, Aruns, and Manto. He also sees the legendary soothsayers and augurs from the classical and biblical world. Each of these characters provides a different perspective on the general theme of forbidden knowledge, while also helping to flesh out Dante’s vision of the Christian afterlife.

One of the most emotionally powerful moments in this canto is Dante’s encounter with the shade of Michael Scot, a famous scholar, and astrologer. Dante is moved to pity at his condition, sparking a rebuke from Virgil who warns him against feeling sympathy for the damned.

In addition, the narrative is paused to allow Dante to provide an aside on the founding of Mantua, his beloved home city. This digression serves as a counterpoint to the bleak atmosphere of the Canto, illuminating Dante’s love for his hometown.

Despite its brutal depictions, Canto XX also includes moments of poetic beauty and philosophical reflection. Throughout the canto, Dante discusses the notion of free will and divine providence, highlighting his belief in the necessity of respecting divine law and the limitations placed on human knowledge.

The canto ends with Dante and Virgil moving on to the next pouch, continuing their journey through Hell. Thus, Canto XX presents an in-depth exploration of the themes of sin, punishment, and divine justice, providing a harsh critique of those who would attempt to see beyond their human limitations.

Canto XXI – The Eighth Circle, Evil Authority

The Fifth Chasm | The Sellers of Public Offices | The Barrators | Demon Escorts

The twenty-first canto presents a highly vivid and dramatic continuation of Dante’s journey through Hell with his guide, Virgil. The journey takes them into the fifth chasm of the eighth circle, Malebolge, where corrupt politicians are punished.

This canto begins with a sudden transition in tone from its preceding one, adopting a comic-like approach that underscores the grotesque reality of Hell. Dante employs humor as a satirical tool against the corruption prevalent in his contemporary Florentine politics.

Our protagonists observe that the fifth chasm is filled with boiling pitch, symbolizing the sticky fingers and dark secrets of corrupt politicians. The “black devils,” or the Malebranche, serve as tormentors here. These demons, carrying prongs, chase and hook the damned souls, ensuring they remain submerged in the pitch. The punishment mirrors their sins; as they concealed their corrupt deeds in life, they must now hide in the pitch from the merciless devils.

A new devil, Barbariccia, is introduced as the leader of the Malebranche. Just as Dante and Virgil are trying to proceed, they encounter this group of devils. The devils are intrigued but apprehensive of Dante, as he’s a living being in Hell.

Seeing this, Virgil steps in, asking to speak with their leader. With his wisdom and eloquence, Virgil persuades Barbariccia to let them pass safely, explaining their journey is willed on high. Struck by these words, Barbariccia consults his comrades, and they agree to guide Dante and Virgil across the chasm.

The devils then arrange themselves in a grotesque procession. To signal their agreement, Barbariccia grotesquely contorts his body, wrapping his arms around his belly and releasing a blast of sound from his behind, a parody of the angelic trumpet. This is a comic element that Dante uses to show the perverse and lowly nature of these demons.

The canto concludes with the devils escorting Dante and Virgil to the edge of the next chasm. One of the devils, Cagnazzo, suspects Dante and Virgil’s motives and raises his concern. However, before any resolution, another sinner surfaces from the pitch, which distracts the devils and creates a cliffhanger that leads into the next canto.

Through Canto XXI, Dante offers a biting commentary on political corruption, emphasizing its insidious, sticky nature and the inevitable divine punishment. This canto is noteworthy for its tone shift, adding a layer of comic relief to the horrific scenes while underscoring the ignoble nature of the damned.

Canto XXII – The Eighth Circle, Corruption

The Fifth Chasm | The Barrators | The Demons | Malebranche

This Canto presents a vivid narrative of their encounter with the barrators (corrupt officials) in the fifth pouch of the Eighth Circle of Hell.

The Canto begins with Dante comparing the gathering of sinners to a group of frogs slipping away at the approach of a water snake, using this analogy to describe the damned souls in the boiling pitch. Dante’s guide, the ancient Roman poet Virgil, has just persuaded a devil, Malacoda, to send some of his minions to guide the pair safely along the cliffs surrounding the pitch-filled pouch. The devils, or “Malebranche,” are eager to torment the barrators, souls who sold political offices for personal gain.

The two poets and their demonic escorts move along the cliffs where Dante observes the sinners. Virgil counsels Dante to hide behind a rock so he can negotiate their safe passage. As Virgil discusses their journey with the leader of the Malebranche, Cagnazzo, another demon named Barbariccia organizes the rest of the demons into a protective troop around Dante.

Suddenly, one of the barrators emerges from the pitch. A demon, Graffiacane, immediately hooks and drags him up to the surface. The sinner is identified as an official from Navarre who is quick to betray his fellow sinners in the hopes of lessening his own torture. He mentions two Italian grafters, Friar Gomita, a Galluran who took bribes to let prisoners escape, and Michel Zanche, another corrupt official from Sardinia.

In an atmosphere of mockery and cruelty, the demons react to the Navarrese’s proposed betrayal. They create a sort of sick game in which they will allow him to swim across the pitch to summon his fellow sinners in exchange for temporary relief from his torment. He dives into the pitch, and as he swims away, the demon Alichino is supposed to chase him, but it’s a trick. The barrator doesn’t resurface where expected, leaving the demons to quarrel among themselves.

Alichino and Calcabrina, infuriated at being deceived, start to fight each other above the pitch, and, in their fury, both tumble into the boiling tar. This provides a moment of comedy and relief in an otherwise dark and punishing setting. The other devils, amused by their comrades’ foolishness, refuse to help them out, and Dante and Virgil seize this opportunity to slip away unnoticed from the chaotic scene.

This Canto showcases the destructive nature of corruption and fraud and illustrates the punitive divine justice the damned are subjected to in Hell. Dante’s depictions of the demons’ chaotic, violent, and foolish behavior also serve to further condemn the sin of barratry by equating it with such traits. In this gruesome and at times farcical narrative, Dante continues to explore themes of guilt, punishment, and the corruptive influence of power.

Canto XXIII – The Eighth Circle, Hypocrisy

The Sixth Chasm | The Hypocrites | Caiaphas

Canto XXIII finds them in the eighth circle of Hell, specifically in the fifth and sixth pouches, which are reserved for the sinners guilty of barratry (corruption by public officials) and hypocrisy, respectively.

The canto starts with the authors using similes to describe their cautious advance, likening themselves to friars who might be traveling secretly out of fear of being caught breaking the monastic rules, or to soldiers on the battlefield who tread warily to avoid falling prey to the enemy.

In the previous canto (XXII), they had seen the barrators—public officials who sold their positions or influence—immersed in a boiling pitch, and punished by demonic ‘Malebranche’ if they dared to lift themselves out of it. Fearing the wrath of these demons, Dante and Virgil flee hastily along the rocky edge of the fifth pouch.

However, the Malebranche demons, alerted to their departure, give chase. Terrified, Dante and Virgil drop down into the sixth pouch of the Eighth Circle, where the hypocrites are punished. The authors use another simile, this time comparing their frantic drop to a peasant who sees a hare in his crop field and sets out to catch it but fails. The demons, frustrated that their prey escaped, attempt to follow, but one of them, Malacoda, stops them, as he had earlier given Virgil permission to pass safely through their territory.

The hypocrites in the sixth pouch are forced to wear cloaks that are gilded and beautiful on the outside, symbolizing the deceptive outward show of their sin, but lined with heavy lead on the inside, symbolizing the weight of their deceit. These cloaks force them to move slowly and laboriously around the circular path of the pouch, crushed under their weight.

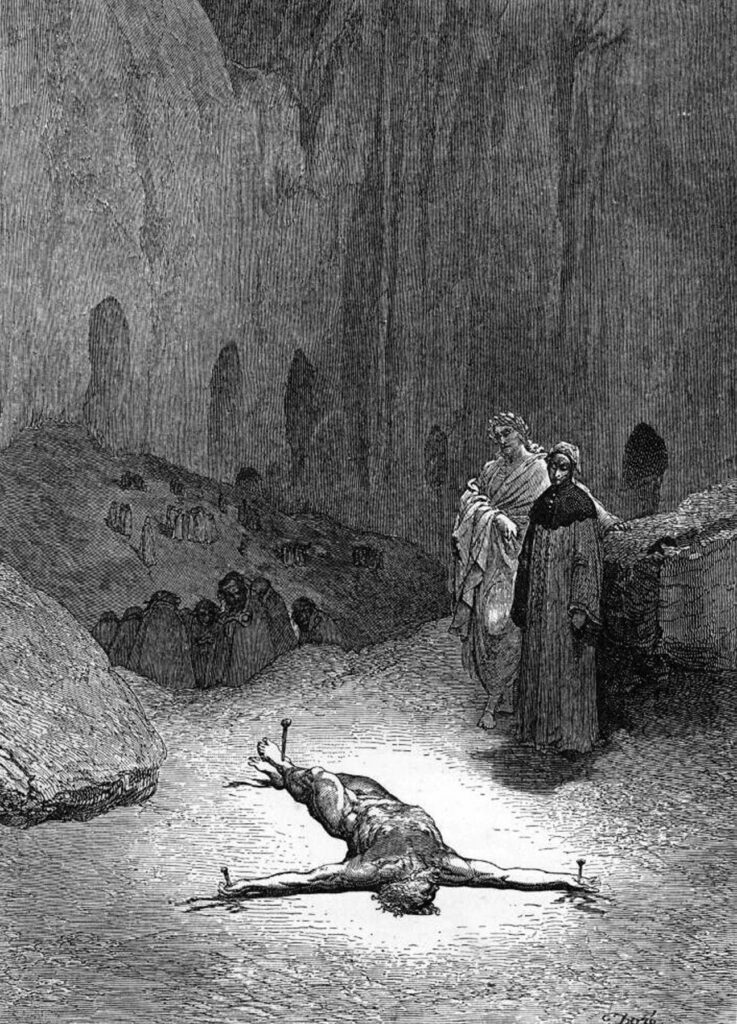

Among these damned souls, Dante recognizes two individuals, Catalano and Loderingo, members of the Jovial Friars, a florentine military order known for their corruption. They inform Dante and Virgil of the pouch’s layout and identify some of the other souls undergoing the same punishment. One particular figure they point out is Caiaphas, the high priest of the Sanhedrin, who counseled the Pharisees to crucify Jesus for the good of the people. As his punishment, he lies crucified on the ground, and the other hypocrites walk over him.

Dante responds to the sight of these sinners with sorrow and sympathy, but also with a certain sense of righteousness. He sees their punishment as a form of divine justice, fitting for the sins they committed in life. By the end of the canto, Dante and Virgil are preparing to move on, presumably to the next pouch and its unique set of punishments.

Thus, Canto XXIII presents an impactful critique of moral corruption and the outward show of virtue. It also reinforces the idea of divine justice, where the punishment corresponds symbolically to the nature of the sin, a central theme in Dante’s vision of Hell.

Canto XXIV – The Eighth Circle, Theft I

The Seventh Chasm | The Thieves | Virgil Exhorts Dante

Canto XXIV, part of Dante’s larger work, starts off with Dante and his guide, Virgil, in the Seventh Circle of Hell, where they continue their journey. This Canto is characterized by Dante’s sheer despair and his struggle to continue, as well as the punishment of thieves in the Eighth Circle, or Malebolge.

At the start of the Canto, Dante alludes to the season of rebirth and growth, spring, but then quickly contrasts it with the dismal surroundings of Hell. Dante admits that he is tired and hesitates to continue the journey, showing his human vulnerability. However, Virgil, the symbol of reason and wisdom, rebukes him sharply. He challenges Dante’s courage and manhood, reminding him of their purpose and how they must press on to complete their mission.

Chastised, Dante summons his strength and follows Virgil, climbing up the rough and craggy rocks of the next bolgia (trench). As they progress, Dante is compared to a man struggling to stay afloat in rough seas. Their journey is physically grueling, highlighting the exertion it requires to surmount sin.

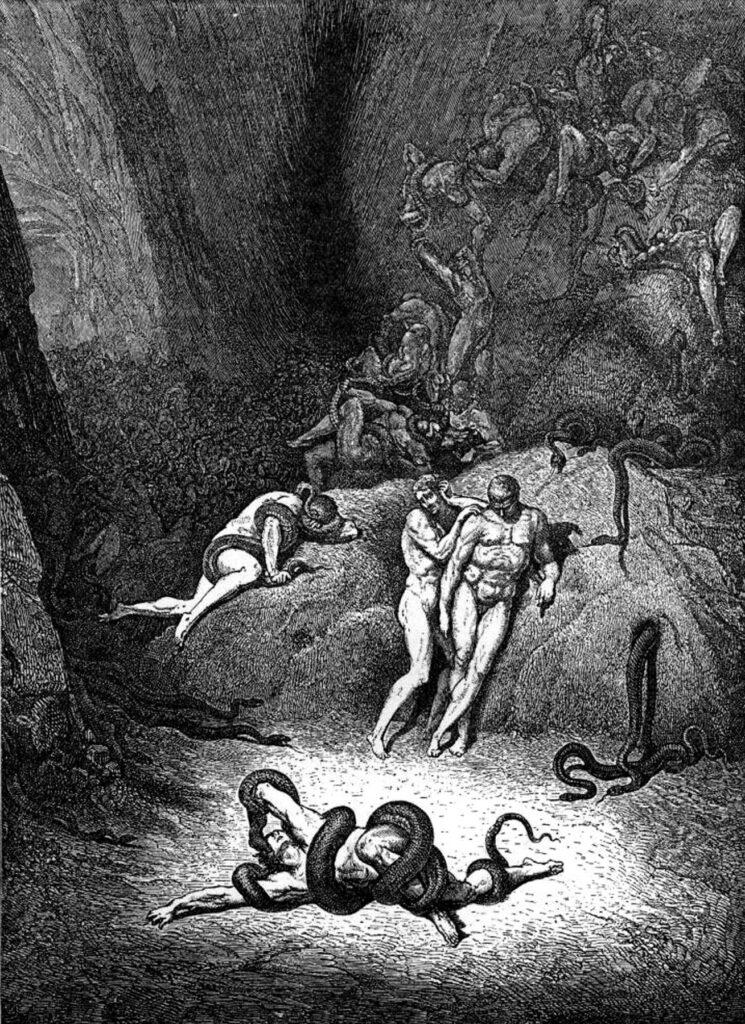

As Dante and Virgil climb, Dante spots numerous souls who are punished by being transformed into reptiles. These souls represent thieves who had disturbed the social order through their fraudulent actions in life. Their punishment in Hell is to have their identities ceaselessly stolen and transformed, just as they stole from others in life.

As they watch, a six-footed serpent lunges at one of the damned souls, who then spontaneously combusts, only to regenerate from the ashes. This grotesque spectacle illustrates the ongoing, relentless punishment of the thieves. Another soul recognized by Dante, Vanni Fucci, is particularly ashamed to be found in this condition and predicts a future conflict in Dante’s hometown, Florence, as a way of retaliation.

As Fucci finishes his prediction, a flight of serpents descends upon him, causing Dante and Virgil to move on to the next pit of the Eighth Circle. The Canto ends on this chaotic scene, which further solidifies the terrifying atmosphere of Hell.

In conclusion, Canto XXIV of Dante’s “Inferno” explores the theme of punishment fitting the crime, as the thieves are subjected to incessant identity theft by reptiles. It also portrays Dante’s perseverance despite physical and emotional exhaustion, prompted by Virgil’s stern guidance. Dante’s human weaknesses and Virgil’s constant guidance underscore the fact that spiritual growth and moral fortitude are hard-won achievements. Moreover, Dante’s Inferno continues to critique the political and social situation of his time through the punishment of specific historical figures.

Canto XXV – The Eighth Circle, Theft II

The Seventh Chasm | The Thieves | The Grotesque Transformations

In Canto XXV, we find Dante and his guide, Virgil, in the Eighth Circle of Hell, where fraudulent sinners are punished. This circle is divided into ten Bolgias, or ditches, each one housing a different form of fraud. Specifically, they are now in the Seventh Bolgia, where the thieves are tormented.

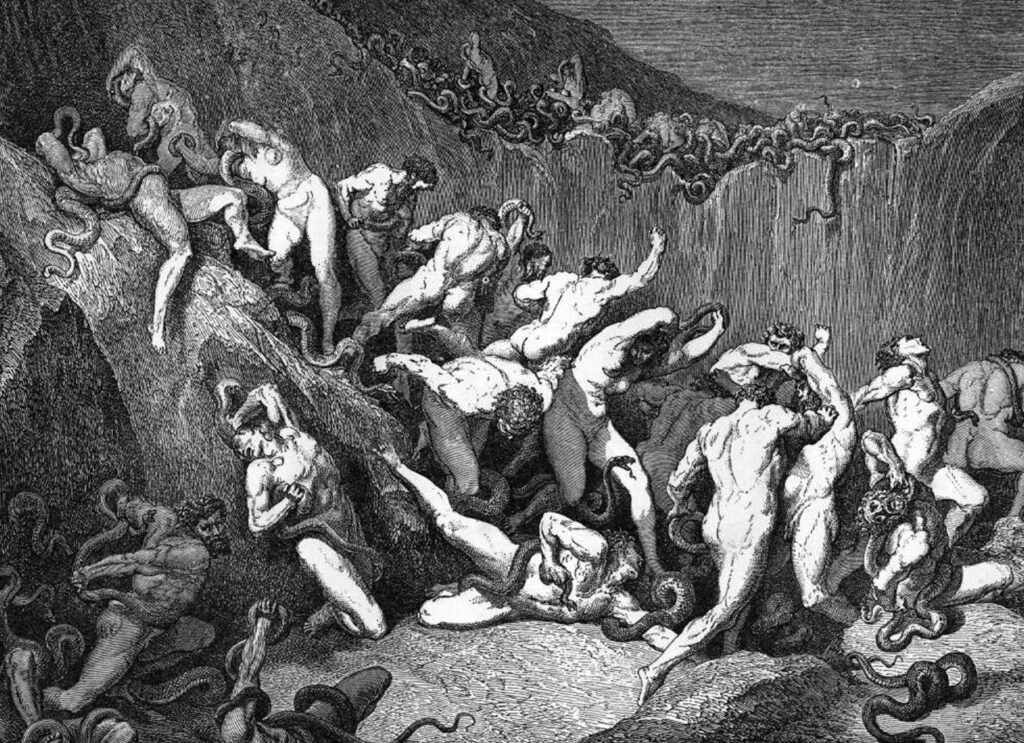

As the canto opens, Dante responds to the damned soul of Vanni Fucci, who has just prophesied Dante’s political exile, with a defiant address. He swears to make Fucci’s name infamous among the living, describing him as a thief who stole from the sacristy of a church in Pistoia. Fucci, angered and shamed, makes obscene gestures towards God, leading to his immediate punishment by a flight of serpents that swoop down and attack him.

Dante and Virgil then turn their attention to other damned souls. Suddenly, a monstrous six-legged serpent lunges at one of the sinners, Cianfa Donati. The snake grapples him, their bodies begin to meld, and undergo a horrifying metamorphosis. The serpent’s cold limbs cause the two bodies to fuse together, creating a grotesque amalgamation. This transformation highlights a central punishment in this bolgia: loss of identity, symbolizing how the thieves in their earthly lives violated others’ substance.

Then, a centaur named Cacus arrives, covered in serpents and a fire-breathing dragon. Cacus is not seen among his centaur brethren in the first circle (Limbo) as he was a thief, and thus deserving of a harsher punishment. The monstrous figure is known in Roman mythology for his theft and subsequent murder by Hercules.

Following this, Dante describes the arrival of three other damned spirits: Agnello Brunelleschi, Buoso degli Abati, and Puccio Sciancato. They are initially wary of the snakes but gradually become accustomed to the presence of the creatures, illustrating the sinners’ adaptation to their punishments.

Agnello, standing apart from the others, is suddenly merged with a serpent, creating another composite creature. At the same time, Buoso, who had been changed into a serpent previously, reappears now in human form. This transmutation further emphasizes the punishment theme of identity loss and transformation in the Seventh Bolgia.

Finally, Puccio Sciancato is recognized as the only one among the three that hasn’t undergone a metamorphosis. Dante notes that his fellow townsman is subjected to a less drastic punishment, though he doesn’t elaborate why.

Canto XXV, thus, is filled with grotesque transformations that echo the sinners’ crimes. It underscores the idea that in Hell, the punishment mirrors the crime. In this case, the thieves are continually robbed of their own identities, their human forms replaced by the serpentine bodies that once symbolized their fraudulent deeds.

Canto XXVI – The Eighth Circle, Evil Counsel I

The Eighth Chasm | The Counsellors | Ulysses and Diomede

In Canto XXVI, Dante and his guide, Virgil, traverse the eighth circle of Hell, specifically the eighth bolgia, which is populated by those guilty of fraudulent counsel. Dante uses this canto to critique the misuse of intellect and talents, represented most poignantly by the presence of the famed Greek hero Ulysses.

The canto begins with Dante’s passionate admonition against Florence, his birthplace, a city marked by discord and chaos. His invective contrasts with the overarching narrative of the canto that extols the virtues of reason and intellect.

Next, Dante and Virgil observe the damned in this bolgia, where they exist in flames, each flame housing one or more souls. Virgil informs Dante that within each flame, a sinner is tormented for eternity, the flames symbolizing the deceit they sowed in life. The punishment reflects the nature of their sins: just as their words once sparked deception, they now burn in eternal flames.

One flame, bifurcated at the top, draws Dante’s attention, and Virgil identifies the souls within it as Ulysses and Diomedes. They are bound together for eternity due to their shared culpability in devising the deceptive stratagem of the Trojan Horse, leading to the downfall of Troy.

Expressing a desire to speak with these sinners, Dante is encouraged by Virgil to temper his admiration for Ulysses, whose intellect and daring led him to disregard the boundaries set by divine will. However, Dante’s request is granted, and Virgil communicates on his behalf, asking Ulysses to recount his final journey.

Ulysses, responding in a narrative that expands upon his Homeric adventures, describes how, after the fall of Troy, he was not content to return home and live a life of peace. He confesses to rallying his crew for one final adventure to the ends of the Earth, eloquently exhorting them to seek knowledge and experience. This bold speech encapsulates Ulysses’ heroic but reckless desire for exploration and understanding, which ultimately leads to his damnation.

Against all divine prohibitions, Ulysses and his crew sailed through the Pillars of Hercules (the modern-day Strait of Gibraltar), which marked the boundary of human exploration. After a long journey, they spotted a distant mountain — Mount Purgatory, the second realm of afterlife in Dante’s cosmology. However, before they could reach it, a whirlwind sank their ship, drowning all aboard and sending Ulysses to his fiery fate in Hell.

As Ulysses’ story ends, Dante is left silent and contemplative, absorbed by the tale of the Greek hero’s final journey. This canto concludes with a feeling of melancholy, lamenting the tragic downfall of one who sought knowledge and experience but disregarded divine limits.

Thus, Canto XXVI of the Inferno serves as a cautionary tale, underscoring the dangerous consequences of misusing one’s intellect and the moral implications of transgressing divine laws in pursuit of personal ambition or curiosity. It’s a canto that, while celebrating human intellect, also warns against its unchecked application, and reflects on the consequences of our actions.

Canto XXVII – The Eighth Circle, Evil Counsel II

The Eighth Chasm | The Counsellors | The Engulfed in Flames

Canto XXVII finds Dante and his guide Virgil in the Eighth Circle of Hell, specifically in the eighth pouch. This area is reserved for fraudulent counselors or advisors, who are punished by being concealed within individual flames.

As the canto begins, Dante is still talking to the spirit of Ulysses, trapped within a flame, when another flame approaches. Virgil identifies the new arrival as Guido da Montefeltro, a Ghibelline who was born in Romagna. Montefeltro was a renowned military leader who later became a Franciscan friar.