Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480–547 AD) is one of the most significant figures in the history of Western monasticism and Christian spirituality. Born in the region of Nursia (modern Norcia, Italy), he came from a family of noble lineage in a society recovering from the fall of the Western Roman Empire. This was a time of political fragmentation, social instability, and cultural transformation, as the remnants of Roman authority were replaced by Germanic kingdoms. Benedict was sent to Rome for his education, as was customary for the sons of aristocratic families. There, he was expected to receive a classical education in rhetoric and philosophy, preparing him for a career in law or public administration. However, Benedict grew disillusioned with the moral decadence and corruption he witnessed in Roman society, which led him to abandon his studies and retreat into solitude to seek God.

After leaving Rome, Benedict lived as a hermit in a cave near Subiaco, dedicating himself to prayer, fasting, and ascetic discipline. His reputation for holiness and wisdom quickly grew, and he began to attract disciples who sought to emulate his way of life. Initially reluctant to take on leadership roles, Benedict eventually accepted the task of guiding these followers, forming a monastic community. This marked the beginning of his legacy as the founder of Western monasticism. His time at Subiaco, however, was not without challenges; he faced opposition, even attempts on his life, from those envious of his growing influence. These conflicts led him to leave Subiaco and establish a new monastery at Monte Cassino around 529 AD, which became the center of his spiritual and organizational work.

At Monte Cassino, Benedict developed his most enduring contribution to Christian monasticism: the Rule of Saint Benedict. This text provided a framework for communal monastic life, balancing prayer, work (ora et labora), and study within a stable, disciplined environment. The Rule emphasized humility, obedience, and the sanctification of daily life, providing clear instructions for the governance of monastic communities. Benedict’s vision of monasticism was practical, adaptable, and deeply rooted in Scripture, particularly the Psalms. It avoided extremes of asceticism and encouraged moderation, fostering a sense of stability and order that was sorely needed in the chaotic socio-political context of early medieval Europe. His Rule would later become the standard for monastic life throughout the Western Church, profoundly shaping the spiritual and cultural development of Christendom.

Saint Benedict’s influence extended far beyond his lifetime. He is venerated as the “Father of Western Monasticism” and was named a patron saint of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964. His emphasis on community, discipline, and the pursuit of holiness became a stabilizing force in a time of turmoil, as Benedictine monasteries preserved classical learning, provided spiritual guidance, and served as centers of social and economic activity. Benedict’s legacy reflects the transformative power of faith in a world in need of renewal, offering a model of Christian life that has inspired countless generations. His life and work stand as a testament to the enduring relevance of spiritual discipline and communal harmony in times of cultural upheaval.

The Rule of Saint Benedict

The Rule of Saint Benedict is one of the most influential texts in Western Christianity, providing a comprehensive guide to monastic life that balances spiritual devotion, communal harmony, and practical governance. Written by Saint Benedict of Nursia around AD 530, the Rule consists of 73 chapters detailing the structure, responsibilities, and spiritual practices of a monastic community. Benedict’s approach emphasizes the cultivation of humility, obedience, and discipline under the leadership of an Abbot, whose role is central to the monastery’s success. The Rule establishes a system of governance, prayer, and labor that has shaped monasticism for centuries, creating a stable framework for spiritual growth and communal life in a turbulent post-Roman world.

The Abbot, discussed extensively in Chapters 2, 3, 64, and others, is the spiritual and administrative leader of the monastery. Benedict emphasizes that the Abbot must be a man of exceptional wisdom, humility, and holiness, who governs as Christ’s representative. Chapter 2 specifies that the Abbot’s authority must serve the spiritual welfare of the monks, balancing discipline with compassion. He is expected to “teach by deeds rather than words” and to ensure that his instructions reflect both divine law and practical wisdom. Chapter 64 further outlines that the Abbot’s election should be based on merit rather than rank, emphasizing the centrality of virtue in leadership. The Abbot is also responsible for resolving disputes, interpreting the Rule, and guiding monks in their spiritual journey, making him the keystone of Benedictine monastic life.

The role of the Prior, addressed in Chapter 65, is subordinate to the Abbot, but nonetheless significant in maintaining the smooth functioning of the monastery. Benedict warns against giving the Prior too much autonomy, as this can lead to rivalry and discord within the community. The Prior is appointed to assist the Abbot in managing the daily operations of the monastery, ensuring the monks adhere to the Rule and fulfill their responsibilities. However, the Rule cautions against the Prior undermining the Abbot’s authority, reflecting Benedict’s concern for unity and order within the monastic hierarchy. This chapter exemplifies Benedict’s pragmatic approach to leadership, emphasizing accountability and collaboration among those in positions of authority.

In Chapter 62, Benedict addresses the presence of a Priest within the monastery. The Priest is tasked with celebrating the sacraments and providing spiritual guidance, but he is subject to the same discipline and humility as any other monk. Benedict emphasizes that no monk, regardless of clerical rank, is exempt from obedience or the communal practices outlined in the Rule. This insistence on equality underscores Benedict’s rejection of pride and ambition, which he saw as antithetical to the monastic ideal. The Priest is not granted any special privileges beyond his liturgical role, reflecting the egalitarian spirit of the Rule and the primacy of spiritual over hierarchical concerns.

The Rule also details the expectations for monks of various roles and statuses, ensuring that every member contributes to the life of the community. Chapters 8–20 focus on the Divine Office, requiring monks to engage in communal prayer at regular intervals throughout the day and night. This disciplined rhythm of prayer reflects the monastic commitment to placing God at the center of life. Chapter 48 addresses manual labor, emphasizing its spiritual value alongside prayer, as encapsulated in the Benedictine motto, ora et labora (pray and work). This chapter ensures that every monk, regardless of age or rank, participates in both spiritual and physical work, fostering humility and communal interdependence.

Benedict also provides guidance for the treatment of younger or weaker monks, demonstrating his pastoral sensitivity. Chapters 37 and 38 emphasize that provisions should be made for the elderly, the sick, and the young, ensuring they are not overburdened by the Rule’s demands. The inclusion of these compassionate instructions reflects Benedict’s understanding that monastic discipline must be tempered with mercy to accommodate individual needs. At the same time, Chapter 58 outlines the rigorous process for accepting new monks, emphasizing the seriousness of the monastic vocation and the commitment required to live under the Rule.

The Rule is deeply rooted in Scripture, drawing on biblical principles to guide monastic governance and spiritual practices. For instance, Chapter 7 on humility echoes Philippians 2:8, calling monks to emulate Christ’s obedience and self-emptying. Chapters on communal prayer and psalmody reflect the Psalms’ central role in the spiritual life, ensuring that Scripture permeates every aspect of monastic devotion. Benedict’s Rule harmonizes the spiritual and practical dimensions of monastic life, creating a framework that cultivates holiness while addressing the realities of communal living.

The Rule of Saint Benedict offers a detailed and balanced vision of monastic life, rooted in spiritual discipline, communal harmony, and wise governance. Through its chapters on the roles of the Abbot, Prior, Priest, and monks, the Rule establishes a hierarchy that promotes accountability while supporting a spirit of humility and service. Its blend of pastoral sensitivity and rigorous discipline reflects Benedict’s profound understanding of human nature and his commitment to creating a sustainable model for Christian living. The enduring influence of the Rule attests to its timeless wisdom, shaping not only monasticism but also broader Christian spirituality and communal structures for over 1,500 years.

The Life of the Benedictine Monk

The Rule of Saint Benedict provides a detailed framework for the daily life of a monk, centering around the Divine Office, a series of eight services of prayer and worship that structure the day. This daily rhythm, known as the Liturgy of the Hours, reflects the monastic commitment to ceaseless prayer and communion with God. The eight services are strategically spaced throughout the day and night, embodying the Psalmist’s call to “pray without ceasing” (Psalm 119:164). In addition to these liturgical obligations, the Rule balances prayer with work (ora et labora), study, and rest, ensuring a harmonious and disciplined life that fosters spiritual growth.

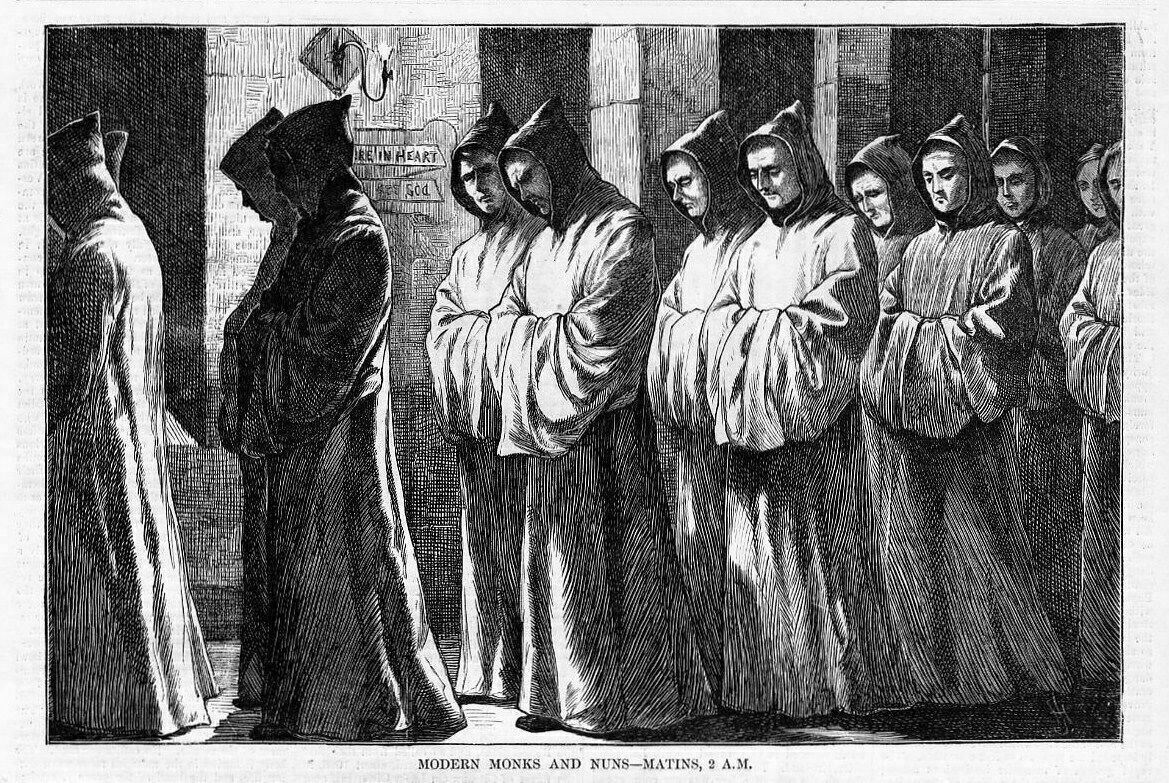

The day begins in the pre-dawn hours with Vigils (or Matins), the first and most solemn prayer service of the day. Taking place around 2 or 3 a.m., Vigils are devoted to extended readings from Scripture and the Church Fathers, combined with psalmody and hymns. This service reflects the monastic ideal of being spiritually vigilant and ready for Christ’s return, in accordance with Psalm 63:6, “I meditate on You in the watches of the night.” The length of Vigils varies depending on the season, with longer readings during winter to fill the extended hours of darkness.

After a brief rest or personal prayer time, monks gather for Lauds, the morning service held at sunrise. Lauds is characterized by a spirit of praise and thanksgiving, celebrating the light of a new day as a symbol of Christ, the “light of the world” (John 8:12). This service includes the chanting of psalms, a hymn, and specific prayers such as the Benedictus (Luke 1:68–79), which praises God’s redemptive work. Lauds sets the tone for the day, reminding the monks of their primary purpose: to glorify God in all things.

Throughout the working hours of the day, monks pause for three shorter services: Prime, Terce, and Sext, named for their timing at the first, third, and sixth hours after sunrise (approximately 6 a.m., 9 a.m., and noon). These services consist of a few psalms, prayers, and a brief reading, providing spiritual nourishment and focus amidst the day’s labor. Terce, in particular, recalls the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost (Acts 2:15) and is associated with seeking the Spirit’s guidance and strength for the tasks ahead. Sext, occurring at midday, offers a moment of reflection and prayerful intercession during the heat and busyness of the day.

Mid-afternoon brings None, the service held at the ninth hour (around 3 p.m.), which marks the transition from the workday to the evening hours. Like the other “little hours,” None is brief but deeply meaningful, providing an opportunity to recall Christ’s suffering and death, which took place at this time (Matthew 27:46). This service reminds the monks of the centrality of Christ’s Passion in their spiritual lives, inspiring them to persevere in their labors and prayers.

As the day winds down, the monks gather for Vespers, the evening service of thanksgiving and reflection. Vespers include the chanting of psalms, hymns, and the Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55), a song of praise that expresses gratitude for God’s saving work. This service, held at sunset, serves as a moment of communal reflection on the blessings of the day and a reminder of the divine providence that sustains all life. It also sets the stage for a peaceful and contemplative evening, preparing the monks for their final prayers before rest.

The final service of the day is Compline, which takes place just before bedtime. This service is kept by simplicity and quiet reverence, offering prayers for protection and peace through the night. The chanting of Psalm 4:8—“In peace I will lie down and sleep, for you alone, Lord, make me dwell in safety”—expresses trust in God’s care. Compline includes an examination of conscience, allowing monks to reflect on their actions and seek forgiveness for any failings before retiring for the night.

| Prayer Rule | Sanctified Time |

|---|---|

| The Night Vigil | Shortly after midnight |

| Lauds (“praise”) | Shortly before daybreak |

| Prime (“first”) | The first hour of the day, sunrise |

| Terce (“third”) | The third hour of the day, midmorning |

| Sext (“sixth”) | The sixth hour of the day, midday |

| None (“ninth”) | The ninth hour of the day, midafternoon |

| Vespers (“evening”) | The early evening |

| Compline (“completion”) | The final service of the day, just before bedtime |

Benedict, St.. The Rule of St. Benedict: An Introduction to the Contemplative Life (p. xxvii). St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Through this structured rhythm of prayer, the Rule of Saint Benedict threads the sacred into the fabric of daily life, ensuring that every moment is oriented toward God. The eight services not only fulfill the biblical exhortation to continual prayer but also create a spiritual atmosphere that transforms mundane activities into acts of worship. This disciplined schedule reflects Benedict’s profound understanding of human nature, balancing physical, mental, and spiritual needs while fostering a deep sense of communal unity and personal holiness. It remains a timeless model of devotion and order, inspiring monastic communities and Christian life across centuries.