Over a series of sessions, I attended a course of lectures on the Prayer Rule from an Orthodox perspective. I didn’t go looking for something new or exotic. I came already convinced that prayer isn’t an add-on to the Christian life but the center of it, and already cautious of approaches that turn prayer into a method or a system to master. What these lectures kept returning to, again and again, was something much simpler and harder: prayer orders a life because it brings the whole person—body, attention, time, and desire—before God every day. Repentance, thanksgiving, intercession, the Jesus Prayer, and spiritual reading were not treated as separate devotions you pick and choose from, but as parts of a single pattern meant to be lived together.

I was also hearing these lectures after earlier reading in Martin Thornton’s work on an Anglican Rule of Life, where he reasons that a prayer rule is not private spirituality but a steady way of sharing in the Church’s life through time, common prayer, and sacrament. Thornton helped me see that love doesn’t remain love for long without some kind of shape, and that without that shape, devotion tends to slide into impulse or inconsistency. The Orthodox material didn’t overturn that; it pushed it further. Where Thornton writes with measured restraint about balance and stability, these lectures were more direct, especially about repentance, bodily prayer, and staying attentive to God. What follows isn’t an argument between traditions, but a straightforward account of what was taught, checked against Scripture, and received as a serious and demanding way of living a life of prayer.

These notes are from the lecture series on The Prayer Rule located here at Patristic Nectar.

Lecture I – Importance of a Prayer Rule

The opening lecture made a clear point from the start: the prayer rule isn’t mainly about organization or discipline. It’s about presence. Prayer was described as the basic way a person actually stands before God in reality, not in theory. If prayer isn’t there, nothing else quite holds.

One thing emphasized early was that no two prayer rules are identical. A rule has to fit a real person with real limits, not an imagined version of ourselves. That said, prayer isn’t something we simply design on our own. Christ Himself assumes prayer as part of following Him. When He speaks about prayer, fasting, and almsgiving, He doesn’t treat them as optional. They are simply part of life with God.

Prayer was also described as something God does in us before it is something we do for God. Paul’s language about the Spirit praying within us matters here. The fact that someone prays at all is already evidence of grace at work. Quoting the fathers, the lecturer made the point that God gives prayer to those who pray. Prayer reveals that something has already been given.

From there, the lecture pressed into love. Prayer isn’t neutral. It shows where love actually lives. Saying “I love God” means very little if there is no space in life given to prayer. This wasn’t presented gently. The claim was simple and uncomfortable: if I don’t pray, I don’t love God. Prayer is how love is practiced, not how it’s described.

That seriousness carried over into commitment. A prayer rule isn’t a hope or a preference. It’s a resolve. The language used was strong: missing the prayer rule is a matter for repentance, not excuse. At the same time, the rule has to be realistic. It must be something that can actually be kept, and only expanded slowly over time.

Morning and evening prayers were recommended as a basic starting point. Additional prayer can happen during the day when time allows, but the emphasis wasn’t on quantity. It was on attention. Inherited prayers—from Scripture and the saints—were described as gifts. They say things we couldn’t invent on our own. As we pray them attentively, they slowly become ours.

The lecture also outlined the basic shape of prayer: when and where we pray, how we pray, and whether prayer is offered alone or with others. Bodily prayer was included from the beginning. Bows and prostrations aren’t meant to be dramatic. They wake the body up and remind it what’s happening. The body learns humility even before the mind does.

Thanksgiving, intercession, and the Jesus Prayer complete the structure. Prayer, we were told, is the highest human work—not because it makes us impressive, but because it places us where we belong. Like breathing, it’s not optional if life is going to continue.

My Notes on Lecture I

- A personal reality of presence and existence.

- Every person’s prayer rule is unique. Unique to a person’s experience and strength.

- The rule is taught to us by the LORD Himself.

- Prayer with almsgiving and fasting is what the LORD assumes per Christ in scripture.

- The Holy Spirit prays within those who are baptized, per Paul in scripture.

- ‘God grants the prayer of he who prays.’ Evagrius in Philokalia.

- The one who prays demonstrates that he has God’s gift of prayer.

- Deeper, sincerely, authentically.

- The prayer rule shows us love for God. It shows us where we stand. If we pray to God, we love God. If we don’t, we don’t love God. ‘The time and practice of prayer shows love for God.’ – John Climacus. If we don’t pray, we don’t love.

- Prayer is a matter of love. If we don’t pray, we do not love God.

- Unshakable personal commitment. It’s not a hope. It’s a law—a personal resolve, no matter what.

- Never miss your prayer rule for any reason whatsoever. To violate is a sin to confess.

- The prayer rule fulfills the highest commandment.

- To say you love God are empty words without a personal prayer life.

- To keep the commandments is to keep in prayer.

- The prayer rule should be accomplishable or doable. Reasonable to perform as a measure of strength. Fashion rules to strengthen and expand over time as advancement becomes possible.

- Morning and evening prayers as a simple starting point, then separate prayers during free time if/as possible. Feel them. Don’t just recite them. Assimilate their meaning as if they came from our minds and hearts. This is the glory of the prayers of the saints and the scriptures.

- We inherit prayers that are inspired that we could never invent ourselves. When we speak them, they’re ours as we come to understand them.

- The parts of the prayer are: a.)when, b.)where, c.)how, and d.)why. Family prayer is separate.

- Prayers consist of opening invocations.

- Rule of prostrations or bows. Usually during the trisagion. Usually at the beginning of your prayers. They wake you up. Bodily prayer of contrition. Deepest humility. Creates within you a spirit of contrition. To water the rest of your prayers.

- Thanksgiving is the heart of prayer, acknowledging the benefits received for God’s glory and your salvation. Fills you with joy.

- Followed by intercessions.

- Usually ends with the Jesus prayer. Because that’s our hope: that the prayer will stay with us. This is the prayer that never really stops, to keep it alive.

- Prayer, according to the holy fathers, is the highest of all human endeavors. To be a co-creator of the God of reality. It’s the deifying virtue.

- Prayer is like breathing.

Scripture References

Prayer as assumed, commanded, and relational

Matthew 6:5–8 — “When you pray…” prayer is assumed by Christ, not optional

Luke 18:1 — the necessity of continual prayer

Psalm 27:8 — seeking the presence of the Lord as relational reality

Prayer as Spirit-given and Spirit-led

Romans 8:26–27 — the Spirit intercedes within believers

Galatians 4:6 — filial prayer produced by the Spirit

Prayer as love and obedience

John 14:15 — love expressed in obedience

John 15:10 — abiding in Christ through obedience

Deuteronomy 6:5 — loving God with heart, soul, and strength

Revelation 2:4–5 — neglect of love revealed through neglect of devotion

Prayer as continual, disciplined commitment

Psalm 55:17 — evening, morning, and noon prayer

Daniel 6:10 — fixed prayer discipline regardless of cost

Colossians 4:2 — perseverance and watchfulness in prayer

Lecture II – Repentance & Bodily Prayer

The second lecture made it clear that prayer is learned. No one knows how to pray naturally. We learn by being taught, by imitating those who pray faithfully, and by submitting ourselves to instruction over time.

The lecturer described prayerlessness as the defining feature of secular life. Not disbelief exactly, but life lived as though prayer were unnecessary. Against that, the saints place prayer at the center of everything.

This led directly into bodily worship. The body isn’t a problem to work around. It’s part of the offering. Scripture assumes that prayer involves posture—standing, kneeling, bowing, lifting hands, remaining still. All of these teach the heart something before the heart knows how to teach itself.

Saint Theophan’s description of the stages of prayer was brought in here: bodily prayer, attentive prayer, and prayer of the heart. Bodily prayer isn’t something to rush past. It sets the conditions for everything that follows.

Prostrations were explained carefully. They cultivate humility and repentance. They aren’t used on Sundays because Sunday is a day of resurrection and dignity, but they are used during the week and especially during Lent. Two forms were described: the full prostration and the smaller bow, or metania.

Quantity, again, was said to be a matter of personal ability or choice. One person may make a few prostrations—another more. The point isn’t exhaustion. It’s reverence, attentiveness, and honesty. Without humility, bodily prayer becomes dangerous. With humility, it trains the whole person.

My Notes on Lecture II

- Prayer is a learned virtue by the holy spirit. We know how prayer went by how we feel inside. Learned by study. Learned by imitation of those accomplished and those more innocent. And to consult with a spiritual elder.

- The lack of prayer defines secular life most. The plague of secular life is prayerlessness.

- Discipline of prayer is the central concern of the saints. This is the keeping of holy tradition. Praying the way they pray (both holy fathers and mothers).

- The Philokalia is on the spiritual life. The common theme is prayer. It’s an apostolic spiritual life. It’s the old, rich wine, and nobody wants the new wine.

- Catechumens learn to pray as the experienced.

- Praying is what it means to be spiritual.

- It is to be in communion with the Holy Spirit.

- Becoming spiritual is cultivating the presence of the Holy Spirit.

- Bodily worship is how we use our bodies in prayer—offering of prayers of body and soul.

- Saint Theophan the Recluse (the path to salvation): three stages of prayer. 1 – bodily prayer, 2 – attentive prayer, 3 – feeling prayer of the heart

- Rom 12:1 rationale for bodily prayer (to include prostrations)

- Bodily positions: bowing to the ground, kneeling, bowing at the waist, standing, hands lifted, arms outstretched, bowing of the head, making the sign of the cross, sleeping on the ground, and singing. All of these are bodily acts of prayer and worship.

- There are over 200 references in scripture about bodily prayer.

- Kathisma (sitting) Psalms or Hymns: There are some cases in which it is appropriate for prayer. The church prescribes sitting during extended psalmody during vespers and orthros (Kathisma – a collection of psalms; 150 psalms are broken into 20 Kathisma. 1. read in vespers, 2. in orthros service). “Kathisma” in Greek means to sit. When doing your prayer rope with the Jesus prayer, do it while seated, relaxed, and undisturbed.

- Akathist Songs: On the Fridays of Lent. Hymn to the Mother of God. You don’t sit.

- Bodily worship is part of who we are. We’re not just souls in shells. We are embodied souls.

- A heart’s disposition is in cooperation with bodily actions of humility. Your body can lead the way.

- Bodily worship fosters an interior disposition through the connection among the body, soul, and mind.

- Bowing to the ground furthers humility. It gives birth to repentance and contrition. It’s body language as expression.

- Prostrations are not made on Sunday as to the dignity of man. It’s the Lord’s day, a day of resurrection, and it’s a celebration of the dignity of man.

- On weekdays or during Lent, you’ll see prostrations. Proscribed in the Lenten services and chiefly in the prayer of Saint Ephrem the Syrian.

- Muslim’s got prostrations from the Christian church.

- In individual prayer, prostrations are usually appointed where they are. Usually at the beginning of the Trisagion prayer, and the Lord’s prayer. Because it enables the person to wake up and to scatter prayers into the person where they’re offered in compunction.

- Two kinds of prostration: Great (full) Prostration and Metania (repentance in Greek). Full prostration while looking at an icon of Jesus Christ, and making the sign of the cross while reciting the Jesus Prayer. Then, making a full bow to the ground and touching the forehead to the ground. Then, coming up to continue or stop.

- Metania is a small prostration from the waist while making the sign of the cross, praying the Jesus prayer, and touching the ground. Metania during Pascha. No great (full) prostrations during Pascha.

- Ignatius says ascetic prayers have a different taste after bows (the arena) because you’ve put yourself in a mode of compunction.

- Quantity is person-specific: 1, 3, 5, 10,… as bodily worship. But not to exhaust you, but they must be reverent and unhurried. Can be used for both the Jesus prayer and intercession.

- Prostrations are used as an act of humility toward others. To others before them, asking for forgiveness. It’s the extremity of humility.

- Must be done with a humble and loving heart; without these, they’re more harmful and can lead to grotesque pride.

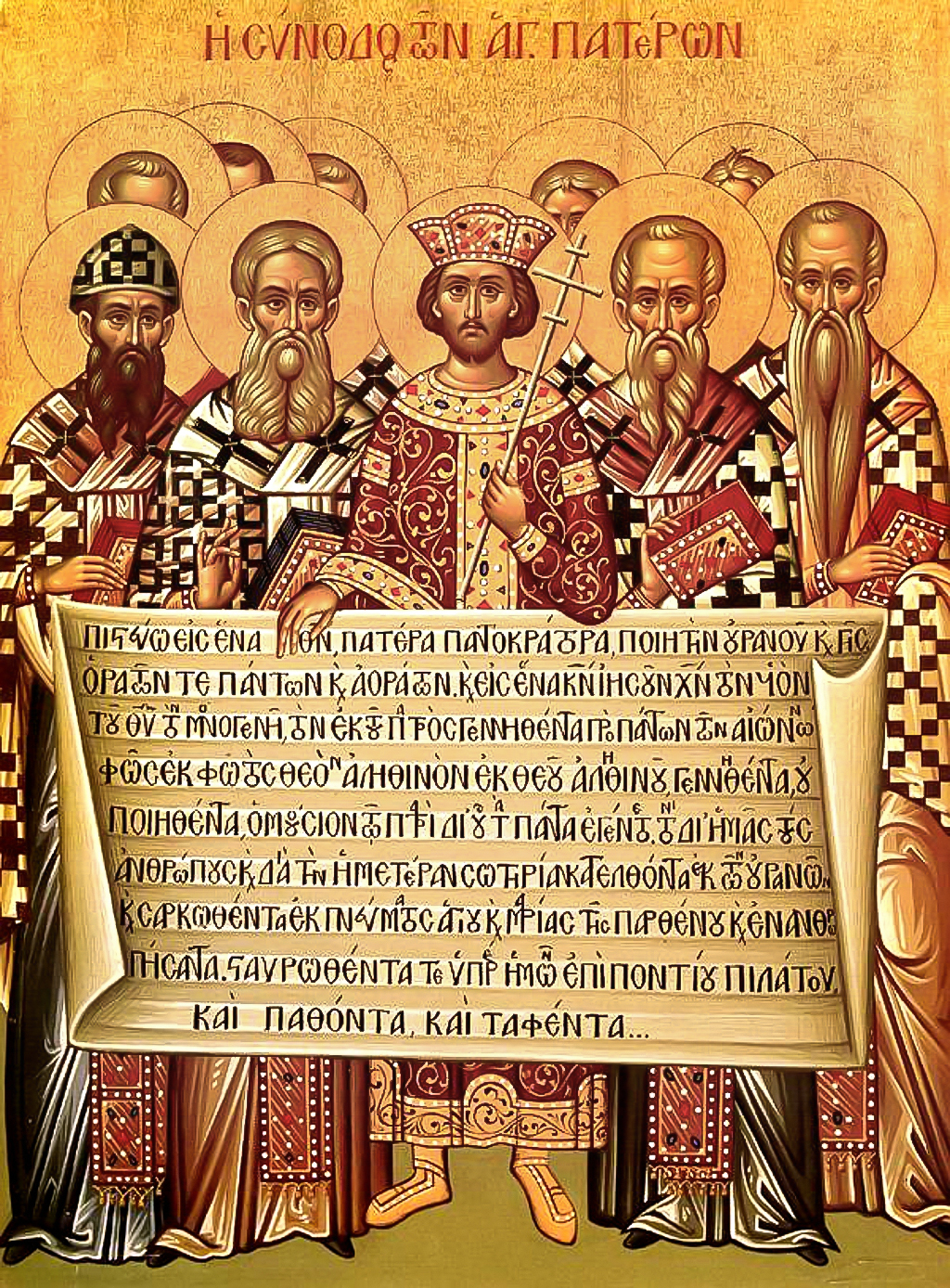

- We pray what we believe and believe what we pray (Prosper of Aquitaine (c. 390–455), Lex orandi, lex credendi (“The law of prayer is the law of belief.”)). Prosper of Aquitaine, a disciple and defender of Augustine of Hippo, during the Pelagian controversy.

- Position of lowliness to proclaim the faith. Bodily acts are expressions of the heart. Without expressions of the heart, they’re occasions of great pride.

- After the six Psalms are said, no sign of the cross is made. The worshiper remains still, as it’s a solemn time of judgment.

Scripture References

Prayer as learned, disciplined, and cultivated

Luke 11:1 — “Lord, teach us to pray”

Hebrews 5:14 — virtue trained by habitual practice

Proverbs 13:20 — formation through wise companionship

Prayerlessness as defining secular life

Psalm 10:4 — life lived without reference to God

Hosea 7:14 — hearts that do not truly cry out to God

Bodily worship commanded and assumed

Romans 12:1 — bodily offering as spiritual worship

Psalm 95:6 — bowing and kneeling before the Lord

1 Corinthians 6:19–20 — the body belonging to God

Prostration, humility, and contrition

Ezra 9:5–6 — kneeling and bodily repentance

Nehemiah 9:5 — posture accompanying corporate worship

Luke 18:13 — bodily posture of repentance and humility

Liturgical restraint and reverence

Habakkuk 2:20 — silence before the Lord

Ecclesiastes 5:1–2 — guarded speech and posture in worship

Lecture III – Thanksgiving and Praise

If repentance tells the truth about us, thanksgiving tells the truth about God. The third lecture insisted that prayer without thanksgiving doesn’t line up with reality. Gratitude isn’t optional. It’s how prayer becomes truthful.

Paul’s repeated calls to give thanks always were highlighted here. Gratitude is the Spirit’s work in us. To withhold thanksgiving isn’t neutrality; it’s resistance.

The prayer of Saint Basil was given as a model. It begins with praise and thanks before any request. God is thanked not only for visible blessings, but for mercy that goes unseen—especially the simple fact of waking up each day under grace and not judgment.

Thankfulness depends on humility. Pride assumes entitlement. Gratitude recognizes mercy. The lecture didn’t avoid saying plainly that realizing we are not in hell is already reason for thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving was extended to everything: creation, the Church, family, friends, teachers, saints, even hardship and correction. Chastisement was described as mercy when it leads us back to God.

The Eucharist itself was named as the center of this posture. Thanksgiving isn’t just personal feeling. It’s the Church’s public way of standing before God. Learning gratitude, we were told, prepares us for heaven, where thanksgiving is the language spoken.

A Basilian Prayer from the Antiochian Prayer Book

We bless thee, O God most high and Lord of mercies, who ever workest great and mysterious deeds for us, glorious, wonderful, and numberless who providest us with sleep as a rest from our infirmities and as a repose for our bodies tired by labor We thank thee that thou hast not destroved us in our transgressions, but in thy love toward mankind thou hast raised us up, as we lay in despair, that we may glorify thy majesty. We entreat thine infinite goodness, enlighten the eyes of our understanding and raise up our minds from the heavy sleep of indolence; open our mouths and fill them with thy praise, that we may unceasingly sing and confess thee, who art God glorified in all and by all, the eternal Father, with thine only-begotten Son and thine all-holy and good and life-giving Spirit, now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen.

My Notes on Lecture III

- Prayers must be permeated by thanksgiving if they’re going to be acceptable to Him. They’re to be offered to Him with an attitude of Thanksgiving.

- It should be ceaseless. Apostle Paul has repeatedly written on this in his letters to the church.

- Rejoicing and giving thanks is the work of the Spirit within us. Without giving thanks, we’re suppressing the work of the Spirit within us. It’s a form of quenching.

- Saint Basil – Applied to morning devotions, (pg 14 of red prayer book) as a model. Beginning with adoration.

- Show and voice gratitude for what you can see, and for what is unseen and innumerable.

- For how he works for every good blessing. His character superintends mercies to us.

- We must live in awe of what He has done.

- Gratitude for time, health, and a clear mind.

- Raised each morning into grace.

- To be thankful, you have to cultivate humility for use within the prayer rule. Combined with a true estimation of ourselves under the weight of sins. To wake up and recognize we’re not in hell is a point of immense gratitude.

- God lets us sleep without retribution. The magnificient never sleeping mercy of God.

- The cultivation of a humble spirit is one of the intentions of liturgical prayer.

- The proud are never thankful. They think that everything they receive, they deserve.

- Thank God for Creation, the Church, Fellowship, Priesthood, Bishop, spiritual mentors, and important people in your life. Your spouse. Your children. Guardian Angel. For the patron saint, and rejoiced in a shared name. For His patience, your friends.

- Thank Him for chastisement. And for the hardship of bearing a cross. For returning to Him by grace through repeated sinful behavior.

- The prayer rule includes prayers of thanksgiving for meals.

- After communion.

- For national blessings and holidays.

- Get a copy of the Akathist of Thanksgiving.

- Your whole approach to the divine liturgy is one of thanksgiving. The Eucharist means thanksgiving.

- To practice this gratitude that helps you to become fit for heaven.

Scripture References

Thanksgiving as essential and continual prayer

1 Thessalonians 5:16–18 — rejoicing, prayer, and thanksgiving united

Ephesians 5:18–20 — thanksgiving as evidence of the Spirit’s filling

Colossians 3:15–17 — life saturated with gratitude

Thanksgiving grounded in humility

James 1:17 — every good gift from God

Psalm 103:2 — remembering divine benefits

Luke 17:17–18 — thanklessness as spiritual failure

Thanksgiving for mercy amid sin

Lamentations 3:22–23 — mercy renewed each morning

Psalm 130:3–4 — mercy leading to reverent fear

Romans 2:4 — kindness leading to repentance

Thanksgiving fulfilled liturgically

Luke 22:19 — Eucharist instituted with thanksgiving

1 Corinthians 11:24 — thanksgiving central to communion

Lecture IV – Intercession

Intercessory prayer was treated as a responsibility, not an option. To pray is always to pray for others. Refusing to pray for others is a failure of love.

Christ’s prayer in John 17 was the model here. Intercession means standing before God for others, asking for their preservation in truth and holiness. We are instructed specifically to pray for those in authority, not because they deserve it, but because peace is a gift.

The lecturer reminded us that we aren’t Abraham. We don’t intercede as patriarchs, but as dependent members of the Church. The prayer of the righteous matters, but righteousness here means faithfulness and humility, not status.

Prayer is shared. We ask others to pray for us. We bring names to the Church. Priestly prayer carries particular weight because of the office, especially within the liturgy, but no one prays alone.

Strong attention was given to family prayer. Husbands and wives are to pray for each other daily. Parents are to pray for their children daily. Job’s practice of early prayer for his children was given as a pattern worth copying.

The lecture briefly addressed saints as intercessors. Saints are powerful not because they are impressive, but because they stand close to God. Prayer is offered only to those recognized as saints, and icons reflect this clearly.

My Notes on Lecture IV

- To pray for those we love, all men, all women. Even our enemies.

- Unceasing prayer for others always.

- To not pray for others is to sin against God Himself.

- Jesus gives us an example in John 17 of what it means to intercede for people. This is an essential part of the prayer rule.

- Pray for Kings and for those in authority. For those who govern to lead a quiet and dignified live.

- This is a tangible expression of love. We pray for those we love—a common dictum.

- Our prayers are not like those of the ancient patriarchs, such as Abraham.

- The effectual prayer of a righteous man accomplishes much (St. James).

- Labor to make our prayers count.

- Those who intercede for loved ones ask others to pray for them too.

- The prayer of a priest is powerful as it is of the office, even from the divine liturgy.

- We ask for the prayers of the prayer warriors (those who are highly practiced).

- We bring the names of our loved ones to others for prayer, where numerous people pray to bring petitions before God.

- Paul requested prayer multiple times. In alignment with the will of God. To pray for dependence accordingly.

- The husband and wife pray for each other every day.

- Pray for children each day.

- Job 1:5 – Rising early in the morning according to the number of them all. For his sons continually. And this was pleasing to God. To stand before guiltless and in peace.

- Get up early each morning to pray for your children.

- A Paraklesis means supplication. An Akathist means standing. These are Greek terms.

- The Holy Fathers teach the doctrine of Divine Impassability. Yet God listens to the prayers of His people. To the fathers, such questions are unwise.

- Saints are powerful intercessors on Earth and much more powerful in heaven.

- Praying to those who are not saints is not sanctioned by the church. Icons of individuals without a halo indicate those who are not prayed to.

Scripture References

Intercession as commanded expression of love

1 Timothy 2:1–4 — intercession for all, including rulers

Matthew 5:44 — prayer for enemies

Ezekiel 22:30 — standing in the gap before God

Christ as the model intercessor

John 17 — Christ’s high-priestly intercession

Hebrews 7:25 — Christ living to intercede

Efficacy and humility in intercessory prayer

James 5:16 — righteous prayer effective

2 Corinthians 1:11 — shared intercession within the Church

Romans 15:30 — Paul’s repeated requests for prayer

Family and parental intercession

Job 1:5 — continual prayer for one’s children

Deuteronomy 6:6–7 — household spiritual responsibility

Intercession of the righteous beyond death

Revelation 5:8 — prayers of the saints before God

Revelation 8:3–4 — prayers offered in heaven

Lecture V – The Jesus Prayer

The fifth lecture focused entirely on the Jesus Prayer. It was described as the prayer that gathers everything else together, not because it replaces other prayers, but because it stays with us when formal prayer ends.

The day begins with a simple acknowledgment that the day belongs to God. Then the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me.” When the fathers speak of “the Prayer,” this is often what they mean.

The prayer is simple and focused. It gives the mind one thing to hold. Repetition builds familiarity and affection. Over time, it moves from the mouth to the mind, and from the mind into the heart.

The use of a prayer rope was encouraged, not as a technique but as help. The prayer can also be used for intercession, carrying others before God by name.

Scripture was clear here: we ask in the Name of Jesus because there is no other name by which we are saved. Saying the prayer often doesn’t heighten emotion so much as it establishes presence. Darkness recedes not through effort, but through staying near Christ.

My Notes on Lecture V

- This is the highest form of prayer.

- We insist on being with Him for each day.

- Let the first words be these. This is the day that the Lord has made. Let us rejoice and be glad in it. Then make the sign of the cross.

- Thoughts should be I belong to God and the day belongs to God.

- Recite the Jesus prayer. John of the Ladder says that the Jesus Prayer should be said upon waking and before going to sleep.

- “The Prayer” is meant as the Jesus Prayer. As found within the gospel, with a deep sense of need. “Lord, have mercy upon me.”

- It’s precious because it’s a monological prayer (a single thought to focus our attention on it).

- It’s useful throughout the day as a single thought centered on Jesus.

- To repeat this prayer is to cultivate a great affection for it.

- The demons hate this name and this practice.

- Say it often with reference. To destroy darkness within us.

- Trisagion, then prostrations at the beginning produces a spirit of compunction to fertilize the rest of the prayers. Prostrations get the blood flowing so we can remember what we’re saying.

- Then comes the Thanksgiving prayers.

- Then, petitions are at the end of our prayers.

- The Jesus prayer completes the prayer rule because the end of the prayer discipline stays with us. To keep it present within the mind. To keep it in mind.

- Keep a prayer rope with you. And say the prayer with each knot of the rope, as many times as pertaining to you.

- Keep the Jesus Prayer with you throughout your day.

- John of the Ladder says to be concentrated on the prayer. To acquire watchfulness.

- Use the prayer in the family. Let your children read it and recite it. Use a prayer rope (chotki).

- The Jesus Prayer is also for intercession, where you can pray the rope for someone. As, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon your servant, or child […name…]. Then, “by their prayers save my soul.”

- Jesus said, “Whatsoever you shall ask in My name, that will I do that the Father may be glorified in the Son. If you ask anything in My name, I will do it.

- “There is no salvation in any other name. For there is no other name under heaven given among men whereby we must be saved” (Acts 4:2).

- Repetition helps move the Jesus Prayer from our mouths to our minds.

- Noetic prayer of the mind is more developed and advanced than intentional voice.

- The prayer is pressed through the demonic and distraction by volume, persistence, and increasing intensity.

- Vices will become reduced and set aside.

Scripture References

Prayer offered in the Name of Jesus

John 14:13–14 — asking in Christ’s Name

Acts 4:12 — salvation found in no other name

Philippians 2:9–11 — the exalted Name of Jesus

Continual prayer and watchfulness

Luke 18:1 — perseverance in prayer

1 Thessalonians 5:17 — unceasing prayer

Colossians 4:2 — watchfulness through prayer

Mark 14:38 — vigilance against temptation

Repetition without vain babbling

Luke 18:13 — repeated cry for mercy

Psalm 136 — faithful repetition grounded in covenant remembrance

Lecture VI – Spiritual Reading

The final lecture made clear that prayer isn’t only spoken. It also listens. Spiritual reading belongs inside the prayer rule, not alongside it.

Scripture comes first. The writings of the saints follow. These texts aren’t read mainly for information but for formation. Chrysostom’s claim was blunt: no one is saved without taking advantage of spiritual reading.

Reading teaches us how to pray. Prayer teaches us how to read humbly. Vigil, fasting, and reading together deepen prayer.

Practical patterns were suggested—reading through Scripture steadily, reading the Psalms continually, and reading the New Testament repeatedly. Patristic works written by saints were preferred over academic treatments. Holiness matters more than novelty.

Reading was encouraged throughout daily life, even in small moments, and with family. In this way, prayer, reading, and life stop being separated.

My Notes on Lecture VI

- Spiritual reading within the prayer rule itself.

- The first degree of the priesthood is to be a reader. A reader who is obsessed with the work of studying scripture.

- Read sacred literature. Patristic literature. It is to receive grace.

- “It is not possible for anyone to be saved without taking advantage of spiritual reading.” -Chrysostom

- Spiritual books, or holy literature and sacred scripture.

- Read the works of the saints. Books that have divine thoughts.

- Mixing this type of reading with prayer helps make it more fruitful.

- Vigil, spiritual reading, and fasting, to yield improved prayer.

- Scripture and holy spiritual books help to build a conversation with the Spirit.

- Reading is included in the prayer rule.

- Patterns for reading include: reading it as the highest treasure. The reading of the scriptures is a meadow according to Chrysostom, with flowers of fragrance and fruit. Not to be read hastily.

- Read through the Bible in a year. Or the Psalter continually, or the reading manner of Sarov (NT only). Read the Epistles according to the calendar of the church.

- Reading Patristic literature: For example, the Popular Patristic Series. Most books are good, but some are horrible. Patristic literature by the Saints is preferred. Five patristic works for every academic work or monograph. Read the saints, East and West.

- Read them throughout your available time. Read with family. Before eating, or after.

Scripture References

Scripture as necessary for salvation and formation

Psalm 1:1–3 — delight in the law of the Lord

Joshua 1:8 — meditation day and night

2 Timothy 3:15–17 — Scripture forming for salvation and obedience

Scripture shaping prayer and communion

John 15:7 — God’s Word abiding shapes prayer

Psalm 119:105 — illumination through divine instruction

Attentive and reverent reading

Nehemiah 8:8 — reading with understanding

Luke 10:39 — attentive listening at the Lord’s feet

Transmission through holy teachers and saints

Hebrews 13:7 — remembering faithful leaders

Philippians 3:17 — imitation of godly examples