With the Hellenization of numerous territories throughout the Mediterranean world, ancient Judea, Samaria, Galilee, and Northern Regions of Israel were immersed in Greek culture and philosophical thought. Widespread was Greek philosophy’s influence in places such as Decapolis, Antioch, and beyond Asia Minor. Even to the extent of Alexandria, Egypt, where Judeaus Philo originated, one could say that what Hellenization was to Judaism is what Gnosticism became to Christianity.1 The influence of Greek philosophical thought upon Judaism was largely speculative, and it touched on every area of Jewish life. More specifically, lifestyle, worldview, religion, ethics, social and interpersonal settings, a focus on individualism became a way to “help” humanity2 from a humanistic standpoint.

Introduction

An overall comparison to the revealed truth of Scripture suggests opposing intentionality. The sharp contrast between Hellenistic philosophical schools and centuries of covenantal life among Jews introduced harmful speculations (2 Tim 2:23). Naturalistic observations and presuppositions brought about “reasoned” conclusions, which also guided conduct, thought, and communication. Philo himself formed an allegorical and symbolic hermeneutic to selectively harmonize the Mosaic covenant with Greek philosophy.

As Philo was a Hellenized Jew, he embraced some facets of Greek culture and its worldview that sought to “teach people how to live.” 2 From foundations of lifestyle to soul-care, Greek philosophy emerged as a religion that produced beliefs and practices as a hollow counterfeit to what Yahweh instructed of the Jews. Caesar Augustus intended to bring Greek philosophy and culture to the “barbarian people” of Israel.3 An early form of imperialism was a leavening of religious and social life within Jewish society.

With Greek philosophy and culture exported to Eastern Mediterranean areas, new and different ideas were lived out and advocated by individuals and communities to affect religious, political, social, and civic life. Together they were a portable method of exported assimilation. It was a self-contradictory people-centered way of reason about the nature of existence, creation, and humanity’s purpose. Hellenization and Greek philosophy had a corrosive and corruptive influence on the Judaic way of life. It held itself out as a symbiosis, yet it was a dilution against Jewish covenantal obligations.

The further in time one goes in the examination of surrounding Hellenization and Greek culture, the emergence of Gnosticism first appear among Christian and Jewish sects. As a form of heretical influence upon the Church and early believers in Christ, it has its roots from within Greek philosophy and religion.

The Nag Hammadi Library

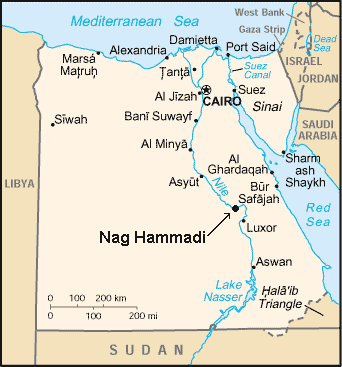

According to Wikipedia, Nag Hammadi (/ˌnɑːɡ həˈmɑːdi/ NAHG hə-MAH-dee; Arabic: نجع حمادى Najʿ Ḥammādī) is a city in Egypt. It is located on the west bank of the Nile river in the Qena Governorate, about 50 miles north-west of Luxor. It had a population of close to 43,000 as of 2007. The Nag Hammadi Library is a collection of writings that were discovered and gave further insights into early Christianity and Gnosticism.

Source References: Nag Hammadi Library of Codices

| Number of Codex, Tractate, Page, and Lines | Name of Tractate | Literary Form | Affiliations |

|---|---|---|---|

| I,1 A,1-B,10 | Prayer of Apostle Paul | Prayer | Valentinian |

| I,2 1,1–16,30 | Apocryphon of James | Apocalypse set in an Epistle | |

| I,3 16,31–43,24 | Gospel of Truth | Meditation or Homily | Valentinian |

| I,4 43,25–50,18 | Epistle to Rheginus Treatise on the Resurrection | Epistolary Treatise | Valentinian |

| I,5 51,1–138,27 | Tripartite Tractate | Theological Treatise | Valentinian |

| II,1 1,1–32,9 | Apocryphon of John | Apocalypse-Revelation Discourse | Sethian |

| II,2 32,10–51,28 | Gospel of Thomas** | Sayings Collection | |

| II,3 51,29–86,19 | Gospel of Philip | Theological Statements | Valentinian |

| II,4 86,20–97,23 | Hypostasis [Nature] of the Archons | Apocalypse (in part) | Sethian |

| II,5 97,24–127,17 | On the Origin of the World | Theological Treatise | |

| II,6 127,18–137,27 | Exegesis on the Soul | Exhortation | Valentinian? |

| II,7 138,1–145,19 | Book of Thomas the Contender | Revelation Dialogue | |

| III,1 1,1–40,11 | Apocryphon of John | (See II,1) | Sethian |

| III,2 40,12–69,20 | Gospel of the Egyptians** | Theological Treatise-Liturgy | Sethian |

| III,3 70,1–90,13 | Eugnostos the Blessed | Epistolary Treatise | Non-Christian |

| III,4 90,14–119,18 | Sophia of Jesus Christ | Apocalypse—Dialogue | Christianized version of III,3 |

| III,5 120,1–147,23 | Dialogue of the Saviour | Revelation Dialogue | |

| IV,I 1,1–49,28 | Apocryphon of John | (See II,1) | |

| IV,2 50,1–81,2 | Gospel of the Egyptians | (See III,2) | |

| V,I 1,1–17,18 | Eugnostos the Blessed | (See III,3) | |

| V,2 17,19–24,9 | Apocalypse of Paul** | Apocalypse | |

| V,3 24,10–44,10 | First Apocalypse of James | Apocalypse—Dialogue | Valentinian |

| V,4 44,11–63,32 | Second Apocalypse of James | Apocalypse | |

| V,5 64,1–85,32 | Apocalypse of Adam | Apocalypse | Sethian—Non-Christian |

| VI,1 1,1–12,22 | Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles | Acts | |

| VI,2 13,1–21,32 | Thunder, Perfect Mind | Revelation Discourse | Sethian |

| VI,3 22,1–35,24 | Authoritative Teaching | Theological Treatise | Valentinian? |

| VI,4 36,1–48,15 | Concept of our Great Power | Apocalypse | |

| VI,5 48,16–51,23 | Plato, Republic 588B–589B | ||

| VI,6 52,1–63,32 | Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth | Revelation Dialogue | Hermetic |

| VI,7 63,33–65,7 | Prayer of Thanksgiving | Prayer | Hermetic |

| VI,8 65,15–78,43 | Asclepius 21–29 | Apocalypse/Dialogue | |

| VII,1 1,1–49,9 | Paraphrase of Shem | Apocalypse | |

| VII,2 49,10–70,12 | Second Treatise of the Great Seth | Apocalypse/Dialogue | |

| VII,3 70,13–84,14 | Apocalypse of Peter** | Apocalypse | |

| VII,4 84,15–118,7 | Teachings of Silvanus | Wisdom Sayings | Non-Gnostic |

| VII,5 118,10–127,27 | Three Steles of Seth | Apocalypse—Hymnic Prayers | Sethian—Non-Christian |

| VIII,1 1,1–132,9 | Zostrianos | Apocalypse | Sethian—Non-Christian |

| VIII,2 132,10–140,27 | Letter of Peter to Philip | Apocalypse set in an Epistle | |

| IX,1 1,1–27,10 | Melchizedek | Apocalypse | Sethian |

| IX,2 27,11–29,5 | Thought of Norea | Hymn? | Sethian |

| IX,3 29,6–74,30 | Testimony of Truth | Homily | Valentinian sect |

| X,1 1,1–68,18 | Marsanes | Apocalypse | Sethian—Non-Christian |

| XI,1 1,1–21,35 | Interpretation of Knowledge | Homily | Valentinian |

| XI,2 22,1–44,37 | Valentinian Exposition (including On Anointing, On Baptism, and On the Eucharist) | Catechism? | Valentinian |

| XI,3 45,1–69,20 | Allogenes | Apocalypse | Sethian—Non-Christian |

| XI,4 69,21–72,33 | Hypsiphrone | Apocalypse? | |

| XII,1 15,1–34,28 | Sentences of Sextus | Wisdom Sayings | Non-Gnostic |

| XII,2 53,19–60,30 | Gospel of Truth | (See I,3) | |

| XIII,3 | Fragments | ||

| XIII,1 35,1–50,24 | Trimorphic Protennoia | Revelation Discourse | Sethian |

| XIII,2 50,25–34 | On the Origin of the World | (See II,5) | |

The Berlin Gnostic Codex is closely related and contains the following:

| Number of Codex, Tractate, Page, and Lines | Name of Tractate | Literary Form | Affiliations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BG 8502,1 7,1–19,5 | Gospel of Mary | Resurrection Gospel/Dialogue and Revelation Discourse | |

| BG 8502,2 19,6–77,7 | Apocryphon of John | (See II,1) | |

| BG 8502,3 77,8–127,12 | Sophia of Jesus Christ | (See III,4) | |

| BG 8502,4 128,1–141,7 | Acts of Peter | Acts | |

“The charts above list all of the tractates in the Nag Hammadi Library, with some indication of literary and doctrinal affinities. The Nag Hammadi documents are cited by codex number (in Roman numeral), tractate number in the codex (Arabic numeral), page, and line numbers of the manuscript.

The Gospel of Thomas is a collection of 112 to 118 (according to different editions) sayings attributed to Jesus, some of which were already known in Greek from a collection in the Oxyrhynchus Papyri. The Gospel of Thomas is perhaps the earliest of the new texts in the collection and demonstrates the existence of collections of sayings of Jesus (a sayings gospel) in the early church. It has a strong encratite or ascetic tone but otherwise is not so pronouncedly Gnostic, although clearly consistent with Gnostic understandings. Although scholarly opinion seems to incline toward emphasizing the extent of the independence of the Gospel of Thomas from the Synoptic Gospels, the age and originality of its individual sayings in relation to the canonical Gospels are much debated.

The Gospel of Truth may be identified with a work of that name that Irenaeus attributes to the followers of Valentinus (Against Heresies 3.11.9). It is not properly a “Gospel,” but a meditation on the truth of redemption. Its theme is that the human state is ignorance, and salvation is by the knowledge imparted by Jesus.

The Gospel of Philip is another sayings or discourse gospel, also from Valentinian circles. It offers information on liturgical practices.

The Apocryphon of John appears to have been one of the most popular of the Gnostic works, for three copies of it were found at Nag Hammadi and one other was previously known. It provides a close parallel to the Gnostic system described in Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.29.

The Epistle to Rheginus, On the Resurrection, sets forth a position close to that of the orthodox in terminology but emphasizes a resurrection of the soul.

The Apocryphon of James, like many documents in the collection, is a post-resurrection revelation of Jesus. He gives blessings and woes through Peter and James. It is argued that the work derives from a sayings collection independent of the New Testament.

The Hypostasis of the Archons describes the efforts of the world rulers to deceive humankind in Genesis 1–6. The myth is close to that of the Ophites or Sethians in Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.30.

The Tripartite Tractate is the most ambitious and comprehensive theological undertaking in the Nag Hammadi corpus. It has points of contact with the Valentinian teacher Heracleon and attempts to present Gnostic teaching, in response to orthodox criticism, in a way more acceptable to the great church.

Eugnostos the Blessed and The Sophia of Jesus Christ are two versions of the same document, the former a letter by a teacher to his disciples and the latter a revelation discourse of Jesus to his followers. The former is important as a non-Christian form of Gnosticism whereas the latter is a Christianized version of the same.

These writings give us more of the inner religious spirit of Gnosticism, whereas the heresiologists concentrated on the bizarre and on the outer structure of the Gnostic systems. Otherwise, the new finds correspond to the picture given by the Christian authors in its main outlines. The non-Christian nature of many tenets of Gnosticism is evident, although it attached itself to the Christian revelation. The concern with the Old Testament points to an area of proximity to Judaism if not to a specifically Jewish origin.” 4

Citations

1 Everett Ferguson, Backgrounds of Early Christianity, Third Edition. (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2003), 308.

2 Ibid, 323.

3 Aaron Valdizan, Historical Background of the New Testament Course Notes, (Unpublished Course Notes, The Master’s University, 2018), 69

4 Everett Ferguson, Backgrounds of Early Christianity, Third Edition. (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2003), 305–306.

Comments are closed.