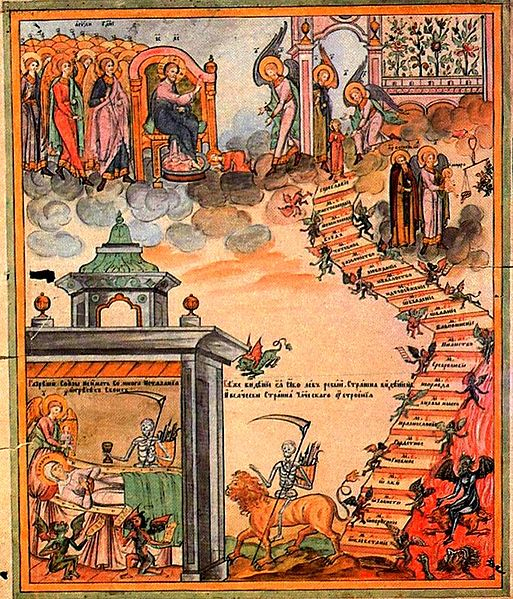

Tollhouses, in Eastern Orthodox theology, refer to a somewhat controversial and debated concept about the soul’s journey after death. The term “tollhouse” is a bit of a metaphor, suggesting that just as one might have to stop at various toll stations along a road, the soul encounters various spiritual “stations” after departing from the body, where it is tested or judged for its deeds, sins, and virtues before reaching its final destination.

Here’s a general overview of the Eastern Orthodox perspective:

- Theology and Origin: The concept is rooted in various patristic writings, liturgical texts, and the lives of the saints. Descriptions of the tollhouses are often allegorical or symbolic, highlighting the soul’s encounters with demons who accuse it of various sins. The prayers of the Church, the intercessions of the saints, and the merits of one’s own life can assist the soul as it journeys through these tollhouses.

- Number and Nature: There are often said to be 20 tollhouses, each corresponding to a particular sin or vice. The demons at each tollhouse try to capture the soul, pointing out the sins it committed in life. If the soul is found wanting or unprepared, it can be dragged down to Hell.

- Controversy: The concept of tollhouses is not universally accepted within the Eastern Orthodox Church. Some view the teaching as a useful allegory or pedagogical tool that underscores the seriousness of sin and the need for repentance. Others see it as a literal depiction of the afterlife. Still, others find it problematic or non-canonical and reject it outright. The degree of acceptance varies among different Orthodox jurisdictions, theologians, and laity.

- Modern Debates: The subject has sparked debates in modern times, especially with the advent of the internet where theological discussions can spread rapidly. Some argue that the tollhouses have been an accepted part of Orthodox teaching for centuries, while others believe that they have been given undue emphasis or misinterpreted in contemporary discussions.

It’s essential to understand that the tollhouses, whether taken literally or allegorically, represent just one aspect of the rich tapestry of Eastern Orthodox eschatology and soteriology. If you’re interested in diving deeper into this topic, it would be beneficial to consult both primary sources (like the Church Fathers and liturgical texts) and secondary discussions (contemporary Orthodox theologians and scholars) to get a comprehensive understanding.

Concept of Tollhouses

The concept of the tollhouses in Eastern Orthodox theology, as mentioned previously, is not universally accepted or standardized across the entire Orthodox world. However, the concept often describes a journey through 20 tollhouses, each representing a specific sin.

Here’s a list of the 20 tollhouses, based on various sources that describe them:

- Murder: This concerns not only physical murder but also includes anger and hatred.

- Adultery: This includes not just the physical act but also lustful thoughts.

- Theft: Greed, stealing, and unlawful possessions.

- Lying: Dishonesty in all its forms.

- Bribery: Love of money and the willingness to compromise integrity for gain.

- Slander: Speaking ill or falsely about others.

- Pride: An inflated sense of self and disdain for others.

- Boasting: Excessive pride in one’s achievements.

- Scoffing: Mocking or deriding others, especially concerning faith.

- Unbelief: Lack of faith or trust in God.

- Witchcraft: Invoking or dealing with evil spirits or practices.

- Envy: Jealousy of others and their accomplishments or possessions.

- Gluttony: Overindulgence in food or drink.

- Laziness: Avoiding work or spiritual duties.

- Usury: Unfair financial practices, especially charging excessive interest.

- Injustice: Unfair treatment of others.

- Ruthlessness: Cruelty or the desire to harm others.

- Mindlessness: Neglect of one’s duties, especially spiritual ones.

- Robbery: Taking from others unlawfully.

- Fornication: Illicit sexual relations.

This sequence might slightly differ depending on the source, but these are the commonly cited sins associated with the tollhouses. It’s worth noting again that while some believers might consider the journey through the tollhouses to be a literal event that souls undergo after death, others view it allegorically, symbolizing the spiritual challenges and consequences of sin in this life.

Patristic Sources of Tollhouses in Orthodox Theology

The concept of the tollhouses, as found in Eastern Orthodox theology, has patristic roots, although the precise nature and interpretation of these sources remain subjects of debate among scholars and theologians. Here’s a brief overview of some of the patristic sources that have been associated with the tollhouse concept:

- St. Athanasius the Great: In his work “On the Incarnation,” St. Athanasius describes how Christ’s incarnation saves humans from the powers of the air and the fear of death.

- St. John Chrysostom: He spoke about demons accusing souls of sins as they ascend to heaven. However, his descriptions don’t lay out a specific system of tollhouses.

- St. Cyril of Alexandria: He wrote about the aerial spirits that seek to hinder the ascension of souls.

- St. Basil the Great: In his homilies, St. Basil makes reference to fearsome powers that challenge souls after death.

- St. Gregory the Dialogist (Pope Gregory the Great): In his “Dialogues,” he tells of the vision of a certain soldier who saw souls being tested by various demonic challenges as they ascended.

- St. Macarius of Egypt: In his homilies, St. Macarius speaks of the soul’s journey after death and the spirits it encounters.

- The Shepherd of Hermas: This early Christian work, while not considered canonical Scripture, was widely read in the early Church. It contains visions and revelations, including depictions of spirits and challenges faced after death.

- The Vision of St. Theodora: This is one of the more detailed and specific patristic sources that describe the tollhouses. St. Theodora’s vision outlines a sequence of tollhouses and the sins associated with each one.

- St. Ephrem the Syrian: His writings also contain references to the soul’s ascent and the demonic challenges it faces.

It’s crucial to note a few things:

- These references often do not explicitly describe a structured set of “tollhouses” in the way that later Orthodox tradition sometimes depicts them. Instead, they offer more general images of aerial spirits or demons accusing or challenging souls.

- Interpretation varies. Not all Orthodox theologians or scholars agree on the exact meaning or importance of these patristic references concerning the tollhouse concept.

- The tollhouse concept is part of a broader tapestry of teachings about the afterlife, judgment, and the soul’s journey. It should be studied in the context of Orthodox soteriology and eschatology as a whole.

If you are interested in the patristic foundations of this concept in depth, it would be wise to read these sources directly and consult Orthodox theological studies on the subject.

Who Were the Patristics?

The term “Patristics” refers to the study of the Church Fathers (or “Patres” in Latin), who were influential Christian theologians and writers primarily from the 1st to the 8th century AD. The Church Fathers played a critical role in shaping Christian doctrine, defending the faith against heresies, and articulating theological concepts in the early Church. They are highly respected in various Christian traditions, including Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and certain Protestant denominations.

The Church Fathers can be generally categorized into several groups based on time periods and regional contexts:

- Apostolic Fathers (Late 1st to Early 2nd century): These are the earliest Christian writers who are believed to have had direct or indirect connections to the Apostles. Key figures include:

- St. Clement of Rome

- St. Ignatius of Antioch

- St. Polycarp of Smyrna

- The author(s) of the Didache

- The author of the “Shepherd of Hermas”

- Ante-Nicene Fathers (2nd to early 4th century): These are the Church Fathers who lived before the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. They defended the faith against early heresies and began formulating theology in a more systematic way.

- St. Justin Martyr

- St. Irenaeus of Lyons

- Tertullian

- Origen

- St. Cyprian of Carthage

- Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (4th to 8th century): These theologians lived after the First Council of Nicaea and during the subsequent ecumenical councils. They dealt with the Arian controversy and other theological challenges.

- St. Athanasius the Great

- The Cappadocian Fathers: St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, and St. Gregory of Nyssa

- St. John Chrysostom

- St. Ambrose of Milan

- St. Jerome

- St. Augustine of Hippo

- St. Cyril of Alexandria

- St. John of Damascus (often considered the last of the Greek Fathers)

- Desert Fathers: These were early Christian monks and ascetics who lived in the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. They are known for their teachings on Christian spirituality and asceticism. Notable figures include:

- St. Anthony the Great

- St. Pachomius

- Evagrius Ponticus

- St. John Cassian

- Western Fathers and Eastern Fathers: The Church Fathers can also be divided based on their geographical and linguistic contexts. Latin-speaking theologians from the Western Roman Empire are often termed “Western Fathers,” while Greek-speaking theologians from the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) are termed “Eastern Fathers.”

The writings and teachings of the Church Fathers have been fundamental in shaping Christian doctrine, liturgy, spirituality, and exegesis. They are frequently cited in theological discussions and remain a vital part of the Christian tradition.

Comments are closed.