Today I completed the book Don Quixote, having followed its long, wayward path across more than a thousand pages. The book—written in two parts, in 1605 and 1615 by Miguel de Cervantes—is often claimed to be the most widely read work of fiction after the Bible. This may well be so, and if true, it is not for lighthearted reasons. Although presented as a comedy and often mistaken for one, this novel is a complex and unsettling mirror. It reflects the absurdity, contradictions, and injustice of human life in a manner far too serious for the shallow category of satire.

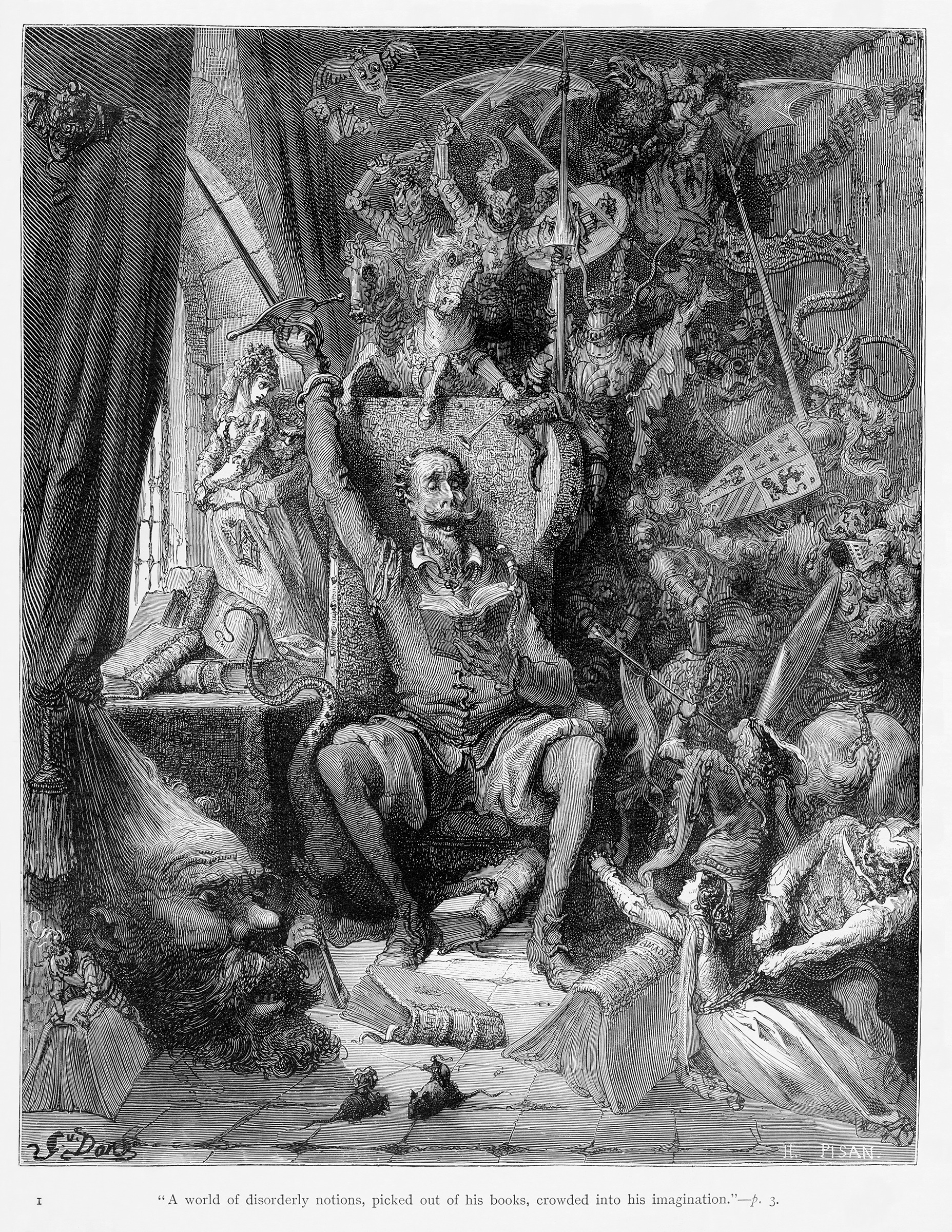

The structure of the book defies linear momentum. Its episodes, while described with the form of “adventures,” are more properly events of coincidence and accident—adventures of meaningless happenstance, of encounters that go nowhere, resolve little, and yet always leave some small impress on the heart. Many scenes concern rescues: not from dragons or giants, but from beatings, poverty, unjust punishment, or the boredom of ordinary life. Cervantes shows us a knight who, though driven by delusion, becomes a source of relief for common people—at least when he is not unintentionally compounding their troubles. His madness, born from obsessive reading of chivalric romances, is both cause and occasion of these acts of rescue.

It is striking how characters in the book often find themselves bewildered by Don Quixote. They are lost in amazement at a man whose mind weaves together sound logic, superior insight, and utter folly without any clear seam between them. This mixture is not merely the device of a humorous madman—it is a portrait of how humans often live, and think, and justify themselves. Through Quixote, Cervantes depicts a mind not unlike our own: grasping for virtue, flailing in confusion, self-deceived, yet somehow noble.

Notes & Reflection

Many of the episodes are interpersonal confrontations, and Cervantes does not hesitate to expose how society mocks and abuses the well-intentioned. The very structure of the book invites the reader to witness, even participate in, the humiliation of Quixote and Sancho. In some cases, this invitation becomes a quiet indictment. The reader laughs, and then wonders why. This is especially apparent in the long section involving the Duke and Duchess, who, as members of the noble class, orchestrate cruel hoaxes upon the knight and his squire purely for amusement. Their wickedness is not impulsive but leisurely—entertainment bred of too much power and too little conscience. They are repugnant not merely for what they do, but for the ease with which they do it. My reaction toward them was not amusement, but contempt.

Beneath the surface of jests, lies often hide. Quixote, for all his speeches on virtue and honor, is not above dishonesty when it serves his narrative or shields his pride. Sancho, more transparent in motive, lies with similar ease to gain food, shelter, or prestige. These are not holy men. They are fallible, sometimes laughable, and often self-deceiving. Yet in the strange bond they share, there is real transformation. From a place of initial animosity, Quixote and Sancho come, gradually, to love one another—first through hardship, then through shared delusion, and finally in a mutual loyalty that grows independent of whether either believes in the other’s fantasies. This progression is one of the most human and redeeming threads in the book.

The novel is also filled with figures who appear only briefly, but leave lasting moral impressions. Claudia Jerónima’s lament reveals the cruelty and irrational torment of jealousy—a moment of raw pathos standing apart from the jesting tone around it. Ana Félix emerges as a portrait of ineffable mercy and quiet strength, whose actions lead to the reconciliation of enemies and the restoration of a broken family. Within the world of bandits, outlaws, and betrayers, she stands as a counterpoint—beauty by virtue, honor in faithfulness, and generosity where no reward is expected.

Quixote’s encounter with Roque Guinart, a leader of bandits, draws a stark contrast. One is a deluded hero, the other a criminal who obeys the cruel logic of his chosen life. Both are trapped in self-created myths—Quixote of righteous knighthood, Roque of villainy, “forced by obligation.” Each man justifies his course, and each lives within the hollow of that self-justification. There is little difference between hero and villain when both are governed by fiction.

The episode of Sancho’s governorship—an elaborate prank meant to mock him—unmasks the pretensions of power. It also reveals that simplicity, humility, and the absence of ambition are often closer to peace than success or control. The peasants, again and again, appear in the background as those who suffer the least from delusions, and who live with a kind of quiet dignity that neither Quixote nor his persecutors understand.

The narrative closes with Samson Carrasco, the “rational” young graduate of the village, who dons armor as the Knight of the White Moon and defeats Quixote in a duel—not for glory, but to force him home and bring his madness to an end. It is a calculated violence, cloaked in benevolence. Whether Carrasco does right or not remains unsettled. He acts with logic and apparent concern, but the method is force. He wins, but at the cost of Quixote’s heart.

In the end, the novel closes not with triumph or defeat, but with relinquishment. Don Quixote, now Alonso Quixano again, returns home, falls ill, and recovers his reason just before death. He renounces the books that once consumed him. His final act is not adventure, but a will: quiet, penitent, and aware that the world he sought to shape could not be changed by dreams. Still, he did dream. And that may have made all the difference.

Book Review

Cervantes has written a book not about madness, but about men—how they seek meaning, how they harm, how they hope. Through its contrasts—truth and illusion, dignity and mockery, humble reality and inflated imagination—it reveals not a farce but a reckoning. It is a book written to make one laugh, but also to wound, and to wonder whether the fool who seeks to do right is really the madman at all.

Written in two parts, it tells the tale of an aging nobleman named Alonso Quixano who becomes so obsessed with books about knights and chivalry that he loses touch with reality. Believing himself to be a knight-errant, he adopts the name Don Quixote, dons a rusty suit of armor, and sets off on a quest to right wrongs, defend the helpless, and win the love of his idealized lady, Dulcinea del Toboso. But his greatest battles are not against dragons or evil sorcerers—they are against windmills, which he mistakes for giants, and against a world that refuses to recognize his noble quest.

At its core, Don Quixote is a tale about the collision between dreams and reality. Don Quixote’s grand ideals lead to a series of absurd and often hilarious misadventures. He charges at flocks of sheep, thinking they are enemy armies, and attacks a group of windmills, convinced they are towering giants. His delusions invite laughter, but there is a deeper side to his story. Cervantes masterfully balances comedy and tragedy, allowing readers to laugh at the foolishness of his hero while also feeling sympathy for his impossible dreams. Don Quixote’s madness is both absurd and heroic, a reminder of how our ideals can inspire us even when they mislead us.

The novel’s humor is heightened by the contrast between Don Quixote and his loyal squire, Sancho Panza. Sancho is a practical, down-to-earth peasant who follows his master, hoping for wealth and adventure, but soon finds himself caught up in Don Quixote’s fantasies. As the two travel together, their bond grows, and Sancho evolves from a mere sidekick to a true friend. He is often the voice of reason, but even he is swept up in the dream of becoming a governor of an island, one of Don Quixote’s many promises.

In this review, Part One and Part Two of the novel cover how Don Quixote’s dreams turn into a mix of comedy, chaos, and heartbreak. From his earliest quests to his final, somber return home, you will see how his story is not just about a madman chasing imaginary giants, but about the power of dreams, the bond of friendship, and the deluded struggle between who we are and who we want to be.

Part One

In Part One of Don Quixote, the story begins with Alonso Quixano, an aging gentleman, who becomes obsessed with books of chivalry. His mind consumed by tales of knights, dragons, and heroic quests, he becomes a knight-errant, renaming himself Don Quixote de la Mancha. He dons old armor, mounts his thin horse, Rocinante, and sets off on a quest to defend the helpless and right wrongs. Before leaving, he selects a local peasant woman, Aldonza Lorenzo, as his lady love, renaming her Dulcinea del Toboso, though she knows nothing of his devotion.

Don Quixote’s first misadventures are disastrous. He attacks a group of merchants for refusing to declare Dulcinea as the most beautiful lady in the world, but they beat him senseless. After a humiliating return home, he recruits a simple but loyal farmer named Sancho Panza as his squire, promising him wealth and the governorship of an island. Together, they set out again, and their adventures became even more absurd. Don Quixote mistakes windmills for giants and attacks them, only to be knocked to the ground. He battles a flock of sheep, believing them to be an enemy army, and charges a funeral procession, thinking it is a band of evil enchanters.

Throughout Part One, Don Quixote’s distorted view of the world leads to endless chaos. He is knighted by a bemused innkeeper who goes along with his madness. At one point, he frees a group of chained galley slaves, believing them to be oppressed men, only for them to rob him and Sancho. His imagination is so powerful that even when he is beaten, he reinterprets his defeats as glorious battles. Meanwhile, Sancho, though practical and often fearful, becomes more caught up in his master’s fantasies, hoping for the island he has been promised.

The story takes a turn when Don Quixote’s friends — the local priest and the barber — decide they must rescue him from his madness. They burn many of his beloved books of chivalry and scheme to bring him back home. Eventually, they capture him, convince him he is under an enchantment, and carry him back in a makeshift cage. But even as he returns home, Don Quixote’s spirit is unbroken, and his mind is still filled with dreams of heroic adventure.

Part Two

Part Two begins with our famous knight recovering at home after his chaotic adventures. But his passion for chivalry hasn’t faded. His loyal squire, Sancho Panza, soon convinces him to set out again, this time with even grander dreams. But unlike their first journey, this time they are famous. News of their mad exploits has spread, and they are recognized wherever they go. Their fame is both a blessing and a curse because now they meet people who have read about them and are eager to play tricks on them.

Their adventures take them to a grand duke and duchess who, knowing of Don Quixote’s madness, decide to amuse themselves by playing cruel pranks on the knight and his squire. They convince Sancho that he has been made governor of an island, but the “island” is just a small village, and his rule is a series of humiliating tests and tricks. Despite his simple wisdom, Sancho quickly discovers that ruling isn’t as easy as he imagined, and the weight of responsibility crushes his enthusiasm. Eventually, he gives up his governorship and returns to Don Quixote, wiser but disillusioned.

Meanwhile, Don Quixote faces his trials. He is tricked into believing that Dulcinea, his ideal lady love, has been transformed into an ugly peasant girl by an evil enchantment. This cruel joke breaks his heart, but he refuses to give up hope, vowing to lift the curse through his heroism. His faith in his chivalric ideals remains strong, even though the world around him seems determined to mock him. He battles imaginary enemies, defends the honor of ladies who don’t need his help, and gives long, noble speeches about virtue and honor that often fall on deaf ears.

One of the most significant encounters in Part Two is with the Knight of the White Moon, who challenges Don Quixote to a duel. The knight defeats him and forces him to promise to return home and abandon his adventures. Broken and humiliated, Don Quixote has no choice but to keep his word. With Sancho by his side, he begins the sad journey back to his village, no longer the bold and deluded knight but a weary old man struggling with the loss of his dreams.

As they near home, Don Quixote’s strength fades. His spirit is broken, and he begins to see the world for what it really is. When he finally reaches his village, he falls ill, and in his final days, he recovers his sanity. He renounces his knightly fantasies, claims his true name, Alonso Quixano, and makes his will. He asks for forgiveness from his friends and Sancho, declaring that he now despises the lies of chivalric books that once consumed his life.

Don Quixote dies peacefully, a man who tried to live by impossible ideals in a world that mocked them. Sancho, devastated, tries to comfort him, still dreaming of more adventures, but Don Quixote has made peace with reality. His death marks the end of an extraordinary tale of madness, friendship, and the clash between dreams and the real world.

Comments are closed.