On July 12, 2024, I completed the first reading of the full Deuterocanon (Apocrypha) from cover to cover. This was the entire collection of books, which includes some that appear within the Catholic and Orthodox canons of scripture. Historically, among Protestant traditions, this was also the case until publishers dropped it. Although the 66 books of the Protestant bible never included the Deuterocanon as Scripture. This reading was from the NRSV in the New Oxford Annotated Bible (NOAB), although it was not the preferred translation; however, the reading was completed cover to cover. From now on, the reading would be from the RSV, King James, and Geneva Bibles because of the unwanted theological liberalism rendered by the NRSV “translators.”

The Apocrypha, a collection of ancient Jewish writings not universally recognized within the biblical canon, offers a fascinating glimpse into the intertestamental period—the centuries between the Old and New Testaments. These texts, which include books such as Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Sirach, and the Maccabees, provide invaluable historical, cultural, and theological insights. Their narratives and teachings illuminate the diverse religious landscape of Second Temple Judaism, revealing the dynamic interplay of faith, tradition, and community during a time of profound change and upheaval. For scholars and lay readers alike, the Apocrypha serves as a critical bridge, enriching our understanding of the milieu in which early Christianity emerged.

This compilation, though not uniformly accepted across all Christian traditions, has had a significant impact on theological discourse and ecclesiastical history. In the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, the Apocrypha is revered as part of the sacred Scriptures, integral to the fabric of liturgical life and doctrinal teaching. Conversely, in the Protestant tradition, these books are often viewed as valuable but non-canonical, appreciated for their historical and ethical content rather than doctrinal authority. This divergence in canonical status underscores the complex nature of the biblical canon and invites readers to explore the Apocrypha with a critical yet appreciative eye, recognizing its role in the broader narrative of Judeo-Christian thought.

Introduction

The Apocrypha, as a collection of intertestamental books, holds varying degrees of significance across different Christian traditions, namely Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant. From a Protestant perspective, the Apocrypha is generally viewed with skepticism and is not considered part of the canonical Scriptures. Protestants, particularly those influenced by the Reformation, adhere to the principle of sola scriptura and limit the Bible to the 66 books found in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. They argue that the Apocrypha, while potentially useful for historical and moral instruction, does not possess the divine inspiration attributed to the canonical books. This view is rooted in the belief that the Apocrypha contains teachings and practices, such as prayers for the dead, which are inconsistent with Protestant doctrine.

In contrast, the Catholic Church includes the Apocrypha, referred to as the Deuterocanonical books, within its canon of Scripture. These texts were affirmed at the Council of Trent in the mid-16th century as an integral part of the biblical canon. Catholics view the Apocrypha as divinely inspired and valuable for doctrine, liturgy, and moral teaching. For example, books like Tobit and Wisdom are cited for their profound spiritual and ethical lessons, which are seen as harmonious with the broader teachings of the Bible. The Catholic Church regards these books as authoritative, supporting doctrines such as purgatory and the intercession of saints, which are less emphasized or rejected by Protestant traditions.

The Eastern Orthodox Church also recognizes the Apocrypha, though with some variations in the specific books included compared to the Catholic canon. Orthodox Christians refer to these texts as Anagignoskomena, meaning “worthy of reading,” and include them in their liturgical practices and spiritual life. The Orthodox tradition, like the Catholic, holds these writings in high regard for their theological, liturgical, and historical contributions. The Apocrypha provides a bridge between the Old and New Testaments, offering insights into the religious and cultural milieu of the Jewish people in the centuries leading up to the advent of Christ. This perspective underscores the holistic view of Scripture within Orthodoxy, where the Apocrypha enriches the spiritual and doctrinal landscape of the faith.

Despite the differing views on the Apocrypha’s canonical status, all three traditions recognize the historical and literary value of these texts. Protestants may study the Apocrypha for its historical context and literary merit, while Catholics and Orthodox Christians integrate these writings more fully into their theological frameworks and devotional practices. The varying acceptance of the Apocrypha highlights the broader divergences in biblical interpretation and theological emphasis among these branches of Christianity, reflecting their unique historical and doctrinal developments. Ultimately, the Apocrypha remains a testament to the rich and complex history of the biblical canon and its interpretation across Christian traditions.

Tobit

The Book of Tobit, a captivating narrative within the Apocrypha, unfolds the story of Tobit, a devout and charitable Israelite living in Nineveh during the Assyrian exile. Tobit, known for his piety and acts of kindness, such as burying the dead, faces a series of misfortunes, including blindness inflicted by bird droppings and the loss of his wealth. Despite his suffering, Tobit’s faith remains steadfast, and his prayers for deliverance are central to the narrative. The story also introduces his son, Tobias, who embarks on a journey that intertwines themes of faith, divine intervention, and familial duty.

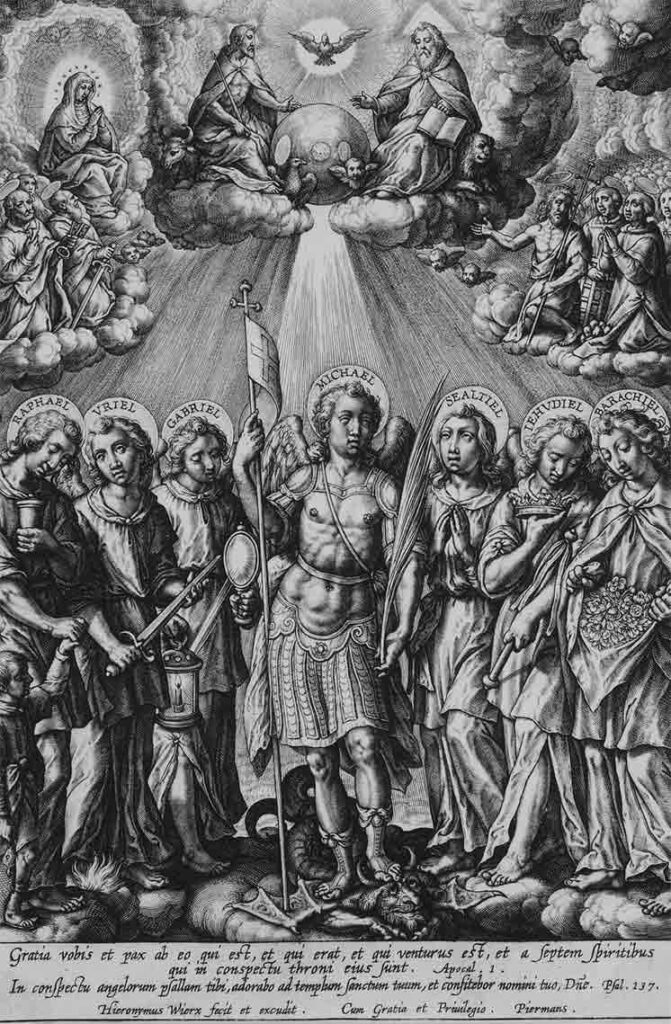

Tobias’ journey is marked by divine guidance in the form of the archangel Raphael, who, disguised as a human, accompanies him. The narrative intricately weaves their adventures, including Tobias’ encounter with Sarah, a relative plagued by a demon that has killed her previous seven husbands. Through Raphael’s counsel and the use of a fish’s gall, heart, and liver, Tobias is able to exorcise the demon and safely marry Sarah. This segment of the story underscores the power of faith and divine assistance, highlighting the importance of trust in God’s providence and the efficacy of prayer.

Upon returning home, Tobias uses the gall of the fish to cure his father’s blindness, further reinforcing the theme of divine intervention and the restoration of fortunes through faith and obedience. Tobit and his family, now reunited and healed, offer prayers of thanksgiving, acknowledging God’s mercy and justice. The narrative concludes with Tobit’s instructions to his son to live righteously, to practice almsgiving, and to remain faithful to God’s commandments. The story of Tobit thus serves as a didactic tale, emphasizing the virtues of piety, charity, and steadfast faith amidst trials.

The Book of Tobit, while not included in the canonical Hebrew Bible, is esteemed within the Catholic and Orthodox traditions for its spiritual and moral teachings. Its themes of divine providence, the efficacy of prayer, and the triumph of righteousness over adversity resonate deeply within these communities. For Protestant readers, Tobit offers a rich narrative that, while not doctrinally authoritative, provides valuable insights into the faith and practices of Jewish communities during the Second Temple period. Overall, the Book of Tobit remains a timeless story of faith, family, and divine intervention, enriching the tapestry of biblical literature and offering profound lessons on the human experience and divine grace.

Judith

The Book of Judith, a compelling narrative within the Apocrypha, tells the story of a heroic Jewish widow named Judith who delivers her people from the threat of the Assyrian army. Set during the time of the Babylonian exile, the tale begins with the Assyrian King Nebuchadnezzar’s general, Holofernes, leading a massive campaign to subjugate the rebellious nations of the West. The Assyrian forces lay siege to the city of Bethulia, a strategic location critical to the defense of Judea. The people of Bethulia, under severe duress and facing imminent starvation, begin to despair, questioning God’s protection and considering surrender.

In this moment of crisis, Judith emerges as a beacon of faith and courage. A pious and wealthy widow known for her devoutness and beauty, Judith chastises the leaders of Bethulia for their lack of faith and boldly asserts that God will deliver them. She devises a daring plan to infiltrate the enemy camp and assassinate Holofernes, thus demoralizing the Assyrian forces and saving her city. Clad in her finest garments and accompanied by her maid, Judith sets out to the enemy camp, where she gains the trust of the Assyrians by pretending to defect and offering valuable intelligence.

Holofernes, captivated by Judith’s beauty and guile, invites her to a banquet in his tent, where he plans to seduce her. Judith seizes the opportunity when Holofernes becomes inebriated and falls into a deep sleep. With unwavering resolve, she decapitates him with his own sword, placing his head in a food sack. Judith and her maid then stealthily return to Bethulia with their grisly trophy. Upon her return, Judith’s people are astonished and jubilant, praising God for their miraculous deliverance. The head of Holofernes is displayed on the city walls, causing panic and confusion among the Assyrian troops, who subsequently retreat in disarray.

Judith’s act of bravery and faith not only saves Bethulia but also reinforces the power of steadfast belief in God’s deliverance. Her story highlights themes of divine justice, the strength of the weak, and the role of women in God’s plan, challenging the traditional gender roles of the time. Judith’s unwavering faith and tactical brilliance make her an enduring symbol of courage and piety in the face of overwhelming odds. Her actions demonstrate that deliverance can come from the most unexpected sources and that faith, combined with decisive action, can overcome even the most formidable of adversaries.

The Book of Judith, while not considered canonical by Protestant traditions, holds a significant place within the Catholic and Orthodox canons, where it is esteemed for its moral and theological lessons. It serves as a powerful narrative of faith and deliverance, illustrating the virtues of courage, wisdom, and unwavering trust in God. For all readers, Judith’s story provides a profound reflection on the dynamics of power, faith, and divine intervention, enriching the broader tapestry of biblical literature with its dramatic and inspiring account of one woman’s pivotal role in the salvation of her people.

Additions to Esther

The Additions to Esther, found in the Apocrypha, enhance the canonical Book of Esther with six supplementary sections that provide deeper theological and literary context. These additions, not present in the Hebrew version but included in the Greek Septuagint, aim to offer a more explicit portrayal of divine intervention and Jewish piety. They serve to highlight the underlying religious themes that are only subtly implied in the canonical text, thereby enriching the narrative with prayers, dreams, and divine actions that underscore the providential care of God for His people.

One of the significant additions includes Mordecai’s dream, which foreshadows the impending danger to the Jewish people and their eventual deliverance. This dream sets the tone for the narrative, emphasizing that the events about to unfold are under divine orchestration. Mordecai’s subsequent discovery of the plot against the king, another addition, portrays him as a righteous and vigilant figure whose actions are divinely guided. These elements underscore the theme of divine justice, as Mordecai’s faithfulness leads to his rise in favor and the protection of his people.

The additions also include prayers by Mordecai and Esther, which are absent in the Hebrew text. These prayers reveal their deep faith and reliance on God during times of crisis. Mordecai’s prayer reflects his anguish and plea for divine intervention, while Esther’s prayer before approaching the king underscores her courage and dependence on God’s deliverance. These prayers provide a theological depth to the characters, illustrating their piety and the role of faith in their actions. This portrayal aligns with the broader Jewish tradition of fasting, prayer, and seeking God’s guidance in moments of peril.

Another critical addition is the expanded version of Esther’s audience with the king, where she faints due to the immense pressure and fear of her task. This humanizes her character, showing her vulnerability and the extraordinary courage she musters to save her people. The narrative culminates in the triumph of the Jewish people, with additional details of their celebration and the institution of Purim as a lasting memorial of their deliverance. The Additions to Esther, thus, enrich the canonical story by infusing it with explicit references to God’s providence, the piety of its protagonists, and the religious significance of their actions, providing a more robust theological framework that resonates with the themes of divine justice and faithfulness.

The Wisdom of Solomon

The Wisdom of Solomon, an esteemed work within the Apocrypha, offers profound reflections on the nature of wisdom, righteousness, and the destiny of the soul. Attributed traditionally to King Solomon, though likely composed much later, this text serves as a philosophical and theological treatise that blends Jewish theology with Hellenistic philosophy. Its primary purpose is to extol the virtues of wisdom as a divine gift and to encourage righteous living by highlighting the rewards of virtue and the consequences of wickedness.

The book opens with a passionate discourse on the love of righteousness and the pursuit of wisdom. Wisdom is personified as a divine, all-encompassing force that guides and sustains the righteous. This wisdom, the text asserts, is more valuable than any earthly possession, offering true immortality and a profound connection with the divine. The author emphasizes that wisdom leads to a virtuous life, aligning one’s actions with God’s will and bringing harmony and peace to the soul. This philosophical underpinning is interwoven with practical advice on living a moral and upright life, underscoring the importance of seeking wisdom above all else.

As the narrative progresses, the Wisdom of Solomon delves into the fate of the righteous versus the wicked. The text assures the faithful that the righteous will be rewarded with eternal life and divine favor, even if they suffer in this world. Conversely, the wicked, despite their earthly success, will ultimately face divine judgment and punishment. This dichotomy serves to comfort and encourage the faithful, affirming that true justice is meted out by God and that righteousness will be vindicated. The vivid descriptions of the afterlife and the divine retribution awaiting the wicked highlight the moral seriousness with which the text approaches the concepts of justice and recompense.

The latter part of the book reflects on the history of Israel, celebrating God’s wisdom and intervention in the lives of the patriarchs and the deliverance of the Israelites from Egypt. This historical reflection serves as a testament to God’s enduring faithfulness and the power of wisdom throughout the ages. The narrative recounts how wisdom guided and protected the chosen people, leading them to freedom and prosperity. By connecting the philosophical musings on wisdom with concrete historical examples, the Wisdom of Solomon reinforces its central theme: that wisdom is a guiding force in both personal righteousness and the broader narrative of salvation history.

In summary, the Wisdom of Solomon stands as a rich, multifaceted text that marries Jewish theology with Hellenistic thought, offering profound insights into the nature of wisdom and its paramount importance in the life of the faithful. It provides a robust framework for understanding the moral and spiritual dimensions of human existence, advocating for a life led by divine wisdom and righteousness. Through its eloquent prose and deep philosophical reflections, the Wisdom of Solomon continues to inspire and instruct readers on the path to a virtuous and meaningful life.

Sirach

The Book of Sirach, also known as Ecclesiasticus, is a profound work within the Apocrypha that offers a comprehensive collection of ethical teachings and practical wisdom. Written by Jesus ben Sirach in the early second century BC, this text aims to provide guidance on how to live a righteous and fulfilling life in accordance with Jewish tradition and the fear of God. Unlike the more abstract philosophical musings found in other wisdom literature, Sirach is deeply rooted in the practical realities of daily life, addressing a wide array of topics including family, friendship, speech, work, and piety.

Opening with a poetic tribute to wisdom, Sirach presents wisdom as a divine attribute, accessible to those who seek it earnestly and live righteously. The text emphasizes that true wisdom begins with the fear of the Lord, a theme that recurs throughout the book. This foundational principle sets the tone for the subsequent teachings, which are presented in a series of maxims and reflective passages. Sirach’s approach is both didactic and pastoral, offering counsel that is meant to be applied in various aspects of personal and communal life. The emphasis on wisdom as a guiding force is evident in its practical advice and moral exhortations.One of the central themes in Sirach is the importance of honoring and respecting one’s parents, a reflection of the text’s strong emphasis on family values. The author extols filial piety, portraying it as a vital aspect of righteousness that brings blessings and longevity. In addition to family relationships, Sirach provides extensive advice on friendship, cautioning against false friends and extolling the virtues of loyalty and integrity. The book’s teachings on speech and conduct are equally comprehensive, advocating for honesty, humility, and discretion as key virtues. This pragmatic wisdom is designed to foster harmonious and just relationships within the community.The Book of Sirach also addresses the ethical dimensions of wealth and poverty, work and leisure. It advocates for a balanced approach to material possessions, warning against both greed and laziness. The author underscores the dignity of labor and the importance of generosity, urging readers to be mindful of the needs of the poor and to practice charity. Sirach’s insights into the human condition are both timeless and culturally specific, reflecting the social and economic realities of Jewish life in the Hellenistic period. The text’s nuanced understanding of human behavior and social ethics is conveyed with a sense of urgency and moral clarity.Concluding with hymns of praise and prayers, Sirach reaffirms its overarching theme of divine wisdom and reverence for God. The final chapters include a eulogy of Israel’s great ancestors, linking the teachings of the book to the broader narrative of Jewish history and tradition. This historical perspective reinforces the continuity of wisdom across generations and highlights the enduring relevance of the book’s teachings. Through its blend of practical advice, moral instruction, and theological reflection, the Book of Sirach offers a rich and multifaceted guide to living a life of virtue and piety, making it a valuable resource for both ancient and modern readers seeking to navigate the complexities of human existence with wisdom and faith.

Baruch

The Book of Baruch, a poignant and reflective text within the Apocrypha, presents itself as a series of writings attributed to Baruch, the scribe and confidant of the prophet Jeremiah. This book is set against the backdrop of the Babylonian Exile, capturing the deep sorrow and repentance of the Jewish people as they grapple with the consequences of their disobedience to God. Baruch opens with a heartfelt confession of sins and a plea for mercy, encapsulating the collective lament of the exiled community. The narrative poignantly underscores the themes of repentance, divine justice, and hope for restoration, reflecting the profound theological insights of its time.

The text transitions into a reflection on wisdom, emphasizing its divine origin and the importance of seeking it to understand God’s ways and commandments. This section of Baruch parallels the wisdom literature tradition, presenting wisdom as the guiding light that leads to a righteous and fulfilling life. The book stresses that true wisdom is found in adherence to God’s law, a message intended to guide the exiled Jews back to faithful living. Baruch’s emphasis on wisdom serves both as a call to repentance and a reminder of the path to spiritual renewal, highlighting the enduring covenant between God and His people.

Concluding with a prayer for deliverance and a poetic reflection on the future restoration of Jerusalem, the Book of Baruch offers a vision of hope and redemption. This hopeful outlook is not merely wishful thinking but is grounded in the steadfast belief in God’s promises and the faithfulness of His covenant. The imagery of a restored Jerusalem serves as a powerful symbol of the ultimate reconciliation between God and His people. Through its blend of confession, wisdom, and prophecy, the Book of Baruch stands as a testament to the enduring faith of the Jewish people during one of their darkest periods, providing a profound meditation on sin, repentance, and divine mercy that resonates through the ages.

The Letter of Jeremiah

The Letter of Jeremiah, a distinct text within the Apocrypha, addresses the Jewish exiles in Babylon with a powerful admonition against idolatry. Purportedly written by the prophet Jeremiah, this letter vividly critiques the futility and absurdity of worshiping idols, a practice rampant in the Babylonian empire. The text’s primary purpose is to fortify the Jewish exiles’ faith, urging them to resist the surrounding culture’s influence and remain steadfast in their devotion to the one true God. The letter underscores the impotence of idols, portraying them as lifeless objects made by human hands that cannot speak, move, or save their worshipers.

Through a series of satirical and scornful descriptions, the Letter of Jeremiah systematically dismantles the credibility and allure of idol worship. The text mocks the rituals and customs surrounding idols, highlighting their inability to protect themselves or their devotees. By emphasizing the irrationality of fearing or venerating these inert figures, the letter aims to expose the hollowness of pagan practices. This critique is not merely an intellectual exercise but a pastoral exhortation, intended to prevent the Jewish exiles from falling into apostasy and to maintain their religious identity amidst a foreign and hostile environment.

In its closing sections, the Letter of Jeremiah reaffirms the enduring covenant between God and His people, emphasizing that their trials in exile are a test of faith rather than abandonment. The letter encourages the exiles to look beyond their immediate hardships and trust in God’s ultimate deliverance and justice. This message of steadfast faith and resilience is a clarion call for the exiles to hold fast to their ancestral traditions and worship the true God. By denouncing idolatry and reaffirming the exclusive worship of Yahweh, the Letter of Jeremiah provides a profound theological and moral directive, reinforcing the distinct identity and spiritual integrity of the Jewish community in exile.

Azariah and the Three Jews

The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews, found within the Apocrypha, enrich the narrative of the fiery furnace in the Book of Daniel with profound expressions of faith and divine deliverance. This text is set during the Babylonian captivity and centers on the unwavering devotion of Azariah (Abednego) and his companions, Hananiah (Shadrach) and Mishael (Meshach). As they are cast into the furnace for refusing to worship Nebuchadnezzar’s golden image, Azariah offers a fervent prayer, acknowledging the sins of the Jewish people and pleading for God’s mercy. His prayer reflects a deep sense of repentance and trust in God’s justice and compassion, setting a spiritual tone that underscores the narrative’s theological depth.

Amidst the flames, the three young men are joined by an angelic figure, who ensures their safety, allowing them to sing a triumphant hymn of praise. This Song of the Three Jews is a jubilant celebration of God’s creation and His enduring faithfulness. The hymn exalts God’s omnipotence and benevolence, calling upon all elements of the universe to join in praising the Creator. This doxology not only underscores the miraculous nature of their deliverance but also serves as a powerful testament to their unshakeable faith and the universal recognition of God’s sovereignty. The juxtaposition of their dire situation with their ecstatic praise highlights the transformative power of faith and divine intervention.

The narrative concludes with the astonishment of King Nebuchadnezzar and his acknowledgment of the power of the God of Israel. The miraculous preservation of Azariah and his companions leads to a decree that honors and exalts their God, demonstrating the impact of their witness on the broader pagan world. The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews, thus, serve as an enduring testament to the themes of repentance, divine mercy, and the power of faith in the face of persecution. This text enriches the canonical account with its vivid portrayal of piety and divine deliverance, offering readers a profound reflection on the sustaining power of worship and the presence of God amid trials.

Susanna

The Book of Susanna, a captivating addition to the Apocrypha, presents a dramatic tale of virtue, corruption, and divine justice set during the Babylonian exile. Susanna, a beautiful and devout woman, becomes the target of two lustful elders who conspire to force her into committing adultery. When Susanna resolutely refuses their advances, the elders falsely accuse her of infidelity, leveraging their positions of authority to substantiate their lies. The community, initially deceived by the elders’ status and the gravity of the accusation, condemns Susanna to death, illustrating the perilous consequences of corrupt leadership and false testimony.

As Susanna faces execution, she offers a fervent prayer to God, declaring her innocence and pleading for deliverance. Her faith and righteousness shine through as she remains steadfast in the face of imminent death, trusting in divine justice. At this crucial moment, the young prophet Daniel intervenes, inspired by God to expose the elders’ deceit. He brilliantly cross-examines the elders separately, revealing inconsistencies in their testimonies about the alleged tryst’s location. Daniel’s clever interrogation not only vindicates Susanna but also condemns the false accusers, who are sentenced to the punishment they sought for her. This turn of events highlights the themes of divine wisdom and justice prevailing over human corruption.

The vindication of Susanna serves as a powerful narrative of integrity and divine intervention. Her story underscores the importance of maintaining faith and righteousness, even when facing grave injustice. It also emphasizes the role of divine providence in protecting the innocent and punishing the wicked. The community’s swift shift from condemning Susanna to celebrating her innocence and punishing the corrupt elders illustrates the restoration of moral order and the community’s ultimate recognition of true justice.

The Book of Susanna, while not part of the Hebrew Bible, holds significant moral and theological lessons within the Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Its narrative underscores the dangers of false witness and the abuse of power, while celebrating the triumph of truth and righteousness through divine intervention. Susanna’s story serves as an enduring reminder of the power of faith and the importance of justice, resonating with readers as a testament to the enduring struggle between corruption and integrity. Through its dramatic and engaging narrative, the Book of Susanna offers a profound reflection on the themes of virtue, faith, and divine justice, enriching the broader tapestry of biblical literature with its timeless message.

Bel and the Dragon

The Book of Bel and the Dragon, an intriguing narrative within the Apocrypha, provides a compelling critique of idolatry and a testament to the power of faith. This text is an extension of the Book of Daniel, featuring the prophet Daniel’s encounters with pagan worship in Babylon. The story unfolds with Daniel challenging the worship of the Babylonian god Bel. The priests of Bel deceive the king into believing that the idol consumes vast amounts of food and drink daily. Daniel, confident in the futility of idol worship, sets a trap to expose the deceit. By secretly scattering ashes on the temple floor, Daniel reveals the footprints of the priests and their families, proving that they, not Bel, consumed the offerings. This clever exposure of the fraud underscores the impotence of idols and the cunning of their worshippers.

Following the downfall of Bel, Daniel confronts another form of idolatry in the worship of a dragon revered as a god. To demonstrate the dragon’s mortality, Daniel feeds it a concoction that causes the dragon to burst open, again proving the futility of idolatry. This act further cements Daniel’s position as a steadfast proponent of monotheism and a relentless adversary of false gods. The narrative then takes a dramatic turn as the enraged populace, infuriated by the destruction of their gods, demands Daniel’s execution. He is cast into a lion’s den, a familiar scenario echoing earlier biblical accounts of his faith and divine deliverance.

In a miraculous turn, Daniel is once again preserved by divine intervention, remaining unharmed in the lion’s den. This final episode reinforces the overarching theme of God’s supremacy and protection over those who remain faithful. The narrative concludes with the conversion of the king, who acknowledges the power of Daniel’s God and orders the execution of those who conspired against him. The Book of Bel and the Dragon, through its vivid storytelling and dramatic confrontations, vividly illustrates the folly of idol worship and the unwavering faith of Daniel. It serves as a powerful reminder of the triumph of monotheism and the protection granted to the faithful, enriching the Danielic tradition with its bold affirmation of divine justice and providence.

1 Maccabees

The First Book of Maccabees, a significant historical text within the Apocrypha, recounts the Jewish struggle for independence against the oppressive Seleucid Empire during the second century B.C. The narrative opens with the death of Alexander the Great and the subsequent division of his empire, setting the stage for the rise of the Seleucid King Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Antiochus’s harsh policies, including the desecration of the Jewish Temple and the imposition of Hellenistic practices, provoke widespread rebellion among the Jewish people. This period of intense persecution and religious suppression ignites the fervent resistance led by Mattathias, a devout priest, and his five sons.

Mattathias’s defiance begins with a dramatic refusal to perform pagan sacrifices, an act of rebellion that sets off the Maccabean Revolt. Upon his death, leadership passes to his son Judas Maccabeus, who emerges as a formidable military commander. Known for his tactical genius, Judas leads the Jewish forces in a series of stunning victories against the superior Seleucid armies. The text vividly describes these battles, emphasizing Judas’s strategic use of guerrilla warfare and his unwavering faith. His leadership not only secures key military successes but also leads to the purification and rededication of the desecrated Temple, an event commemorated by the festival of Hanukkah.

As Judas’s campaign progresses, his objectives expand from mere survival to the establishment of Jewish autonomy. Despite facing numerous challenges, including internal dissent and external threats, Judas skillfully navigates these obstacles, forming alliances with powerful entities like the Roman Republic. These diplomatic efforts are portrayed as crucial in bolstering the Jewish cause, reflecting the Maccabean leadership’s political acumen. The narrative celebrates Judas’s victories, which reassert Jewish control over Jerusalem and its surrounding regions, symbolizing a significant restoration of Jewish sovereignty.

The book also delves into the struggles and challenges that follow Judas’s death in battle. His brothers Jonathan and Simon continue the fight, demonstrating remarkable resilience and adaptability. Jonathan’s tenure as high priest and leader is marked by a blend of military engagements and political negotiations, securing the stability and survival of the Jewish state. Simon’s leadership heralds a period of relative peace and consolidation, during which the Hasmonean dynasty is firmly established. His reign is characterized by effective governance, the fortification of cities, and the enhancement of religious and civic life, marking a high point in Jewish self-governance.

The First Book of Maccabees does not shy away from depicting the complexities of leadership and the often harsh realities of the fight for freedom. The narrative highlights the internal divisions and external pressures that continually threaten the stability of the Jewish state. Yet, through the perseverance and faith of the Maccabean leaders, the book conveys a powerful message of hope and resilience. Their ability to maintain their cultural and religious identity in the face of overwhelming odds is a central theme, offering readers an inspiring account of determination and divine providence.

Overall, the First Book of Maccabees stands as a monumental work that captures the essence of the Jewish struggle for independence and the enduring spirit of resistance against oppression. Its detailed recounting of historical events, combined with its portrayal of the Maccabean leaders’ faith and courage, provides a rich and nuanced understanding of this pivotal period in Jewish history. The narrative not only commemorates the military and political achievements of the Maccabees but also underscores the profound religious and cultural significance of their fight for freedom. Through its compelling storytelling, the First Book of Maccabees offers a timeless testament to the power of faith, the pursuit of justice, and the unyielding quest for autonomy.

2 Maccabees

The Second Book of Maccabees, an essential historical and religious text within the Apocrypha, presents a detailed and dramatic account of the Jewish struggle for religious freedom against the Seleucid Empire. Unlike the First Book of Maccabees, which focuses on a chronological historical narrative, the Second Book of Maccabees offers a more theological and moral perspective, emphasizing the themes of martyrdom, divine intervention, and the sanctity of the Jewish Temple. The book begins with two letters addressed to the Jews in Egypt, encouraging them to celebrate the feast of Hanukkah and recounting the purification of the Temple under Judas Maccabeus. This introduction sets the tone for the subsequent narrative, highlighting the religious significance of the events described.

The narrative proper opens with the reign of the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes and his aggressive efforts to Hellenize the Jewish population. The desecration of the Temple and the suppression of Jewish religious practices provoke widespread outrage and resistance. The book vividly depicts the cruel persecutions inflicted upon the Jews, emphasizing the moral and spiritual resilience of those who remain faithful to their traditions. One of the most poignant sections recounts the martyrdom of Eleazar, an elderly scribe, and a mother and her seven sons, who endure horrific tortures rather than violate their faith. These stories of martyrdom serve to inspire and fortify the Jewish community, underscoring the profound conviction that fidelity to God outweighs even the threat of death.

As the narrative progresses, Judas Maccabeus emerges as a central figure, leading the Jewish resistance with remarkable courage and strategic acumen. The book details his military campaigns, including the miraculous victories attributed to divine intervention. The liberation of Jerusalem and the rededication of the Temple are portrayed as pivotal moments, symbolizing the triumph of faith and divine justice over oppression. The narrative highlights the purification and restoration of the Temple, reinforcing its centrality to Jewish religious life and identity. Judas’s leadership is depicted not only in terms of his military prowess but also his unwavering commitment to the preservation of Jewish law and worship.

One of the distinguishing features of the Second Book of Maccabees is its emphasis on the theological interpretation of events. The author frequently attributes successes and failures to the will of God, illustrating the belief in divine providence and retribution. This perspective is evident in the accounts of supernatural occurrences, such as heavenly visions and angelic interventions, which serve to validate the righteousness of the Jewish cause. The book also underscores the importance of prayer, fasting, and other religious observances as means of seeking God’s favor and protection. This theological framework provides a deeper understanding of the spiritual dimensions of the Maccabean struggle.

The latter part of the book focuses on the continued conflicts under the leadership of Judas and his brothers, as well as the internal divisions within the Jewish community. The narrative does not shy away from depicting the complexities and challenges of maintaining unity and faith in the face of external threats and internal strife. The deaths of key figures, including Judas Maccabeus, are portrayed with a sense of tragic heroism, reflecting the high cost of the struggle for religious and political autonomy. The book concludes with a reflection on the enduring legacy of the Maccabean revolt, emphasizing the importance of remembering and honoring those who sacrificed their lives for the preservation of their faith.

In summary, the Second Book of Maccabees offers a rich and multifaceted account of the Jewish resistance against Seleucid oppression, blending historical narrative with theological reflection. Through its vivid portrayal of martyrdom, divine intervention, and the sanctity of the Temple, the book underscores the central themes of faith, perseverance, and divine justice. It serves as a powerful testament to the resilience of the Jewish people and their unwavering commitment to their religious identity and traditions. The Second Book of Maccabees not only commemorates the heroism of the Maccabean leaders but also provides profound insights into the spiritual and moral dimensions of their struggle, making it a timeless and inspiring work for readers of all generations.

3 Maccabees

The Third Book of Maccabees, distinct from its predecessors in focus and content, provides a gripping narrative centered on the plight of the Jewish community in Egypt under the reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator. Unlike the previous Maccabean texts, which chronicle the military and religious struggles against the Seleucid Empire, this book delves into the experiences of Jews in the diaspora, specifically their persecution and subsequent divine deliverance. The story unfolds with Ptolemy’s visit to Jerusalem after his victory over Antiochus III at the Battle of Raphia. His curiosity leads him to attempt entry into the Holy of Holies, a sacrilegious act prevented by divine intervention, which leaves him humiliated and enraged against the Jewish people.

The king’s wrath manifests in severe decrees aimed at suppressing the Jewish population in Alexandria. Ptolemy orders the registration of all Jews and their assembly in the city’s hippodrome, intending to mark them with ivy leaves, signifying their allegiance to Dionysus. However, the Jews, adhering to their faith, refuse, leading to their brutal treatment. The narrative vividly describes their suffering, including imprisonment and the threat of mass execution by intoxicated elephants. This scenario underscores the Jews’ steadfastness in their faith and their unwavering refusal to abandon their religious identity despite the king’s relentless persecution.

At the critical moment of their impending execution, divine intervention once again plays a pivotal role. An angel appears, causing the elephants to turn against Ptolemy’s own troops, a miraculous event that saves the Jews from certain death. This dramatic deliverance is a powerful testament to the protective power of God and His faithfulness to His people. The king, struck by these supernatural occurrences, has a change of heart, and not only releases the Jews but also bestows upon them honors and privileges, recognizing the might of their God. This turn of events highlights the themes of divine justice and mercy, reinforcing the belief in God’s active role in the lives of the faithful.

The Third Book of Maccabees concludes with the Jewish community celebrating their deliverance, establishing a day of thanksgiving and commemorating their miraculous salvation. This narrative, rich with themes of faith, persecution, and divine deliverance, offers a unique perspective on the Jewish experience in the diaspora. It emphasizes the power of steadfast faith and the belief in divine protection against overwhelming odds. The book serves as a reminder of the enduring covenant between God and His people, providing a source of hope and inspiration for those facing oppression. Through its dramatic storytelling and theological insights, the Third Book of Maccabees enriches the Apocryphal canon, offering profound lessons on faith, resilience, and divine providence.

4 Maccabees

The Fourth Book of Maccabees, an evocative text within the Apocrypha, offers a unique blend of history, philosophy, and theology, focusing on the concept of reason over passion. Set against the backdrop of the brutal persecution of Jews under the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, this book is framed as a philosophical discourse that underscores the supremacy of pious reason over the irrational impulses of fear and pain. The narrative centers on the martyrdom of Eleazar, a venerable scribe, and a mother and her seven sons, whose steadfast faith and reasoned courage exemplify the triumph of religious conviction over physical suffering.

The narrative begins with an exploration of the philosophical idea that reason, when guided by piety, has the power to conquer the passions, even in the face of extreme torture. Eleazar’s martyrdom is presented as a profound demonstration of this principle. Despite being subjected to horrific tortures, Eleazar remains resolute, choosing to endure suffering rather than betray his faith. His unwavering stance serves as an exemplary model of rational piety, illustrating how reason can fortify the soul against the most severe trials. The text delves into his internal resolve, portraying him as a paragon of virtuous rationality.

The story then shifts to the harrowing account of the mother and her seven sons, who are similarly tortured for refusing to violate their religious laws. Each son, in turn, expresses their commitment to their faith and the belief in divine justice, enduring unimaginable pain with remarkable composure. The mother, witnessing her sons’ sufferings, encourages them to remain steadfast, drawing strength from her own deep faith and rational conviction. Her profound speeches to her sons and the calm acceptance of their fate by each young man underscore the central theme that pious reason can overcome the most intense physical and emotional anguish.

Concluding with reflections on the significance of these martyrs’ sacrifices, the Fourth Book of Maccabees highlights the inspirational power of their example. The text asserts that their martyrdom not only demonstrates the supremacy of reason over passion but also serves to strengthen and purify the broader Jewish community. Their acts of faith and reason are presented as a form of spiritual victory, affirming the eternal rewards that await those who remain true to their religious convictions. Through its philosophical discourse and vivid narrative, the Fourth Book of Maccabees offers a profound meditation on the interplay between faith, reason, and the human capacity to endure suffering for a higher cause. This work enriches the Apocryphal literature with its unique blend of philosophical rigor and theological depth, providing timeless lessons on the power of reasoned faith.

1 Esdras

The First Book of Esdras, an engaging historical text within the Apocrypha, revisits and expands upon the events surrounding the return of the Jewish exiles from Babylon and the subsequent restoration of Jerusalem and its Temple. The narrative begins with the reign of King Josiah of Judah, detailing his religious reforms and the celebration of the Passover, which are portrayed as a return to the faithful worship of God. This opening sets a tone of religious renewal and highlights the importance of adherence to the Law.

As the story progresses, the focus shifts to the period following the fall of Jerusalem, emphasizing the pivotal role of Zerubbabel and Jeshua in leading the first wave of exiles back to their homeland under the decree of King Cyrus of Persia. This return is marked by the laying of the foundation for the Second Temple amidst great rejoicing, but also facing opposition from local adversaries. The narrative underscores the challenges and setbacks faced by the Jewish community as they strive to rebuild their sacred city and reestablish their religious practices. The perseverance and faith of the returning exiles are central themes, illustrating their unwavering commitment to their heritage and their God.

One of the unique elements of the First Book of Esdras is the inclusion of the famous tale of the debate before King Darius, which is not found in the canonical books of Ezra and Nehemiah. This story features a contest between three young bodyguards of King Darius, each presenting a different argument on what is the strongest force in the world. Zerubbabel, one of the contestants, argues that women and truth are the strongest. His eloquent and persuasive argument, especially highlighting the power of truth, wins the contest, and as a reward, he secures the king’s support for the Jewish people and their efforts to rebuild Jerusalem. This episode not only adds a literary and philosophical dimension to the narrative but also serves to reinforce the themes of wisdom and divine providence.

The book concludes with the successful completion of the Temple reconstruction under the leadership of Zerubbabel and the high priest Jeshua, despite ongoing obstacles. The narrative praises the communal efforts and the renewed dedication to the Law, reflecting a period of spiritual revival and national restoration. The First Book of Esdras, with its blend of historical recounting and unique literary additions, offers a rich portrayal of the struggles and triumphs of the Jewish people during a critical period of their history. It emphasizes themes of faith, perseverance, and the enduring power of truth, providing readers with a deeper understanding of the Jewish experience during the post-exilic era. Through its compelling storytelling and focus on divine faithfulness, the First Book of Esdras enriches the Apocryphal literature and offers timeless lessons on the resilience of faith and the importance of religious and communal identity.

2 Esdras

The Second Book of Esdras, a profound and complex text within the Apocrypha, delves into themes of divine justice, eschatology, and theodicy through a series of visions granted to the prophet Ezra. Written during a period of great turmoil and suffering for the Jewish people, this book addresses their existential questions and struggles, offering a deep exploration of God’s plans and the ultimate fate of humanity. The narrative begins with Ezra’s anguished prayers and laments over the fate of Israel, expressing doubts about God’s justice in light of the widespread suffering and devastation experienced by his people.

In response to Ezra’s heartfelt inquiries, an angelic figure named Uriel is sent to guide him through a series of visions and explanations. These revelations are profound and multifaceted, encompassing symbolic imagery and apocalyptic themes. One of the key visions presented to Ezra is the vision of the woman in mourning who transforms into a magnificent city, symbolizing the restoration and future glory of Jerusalem. This vision underscores the theme of transformation and redemption, offering hope amidst despair by illustrating God’s eventual plan to restore His people and their city to their former glory.

The Prayer of Manasseh

The Prayer of Manasseh, a brief but poignant text within the Apocrypha, presents a heartfelt plea for forgiveness from King Manasseh of Judah. Known for his idolatrous reign and extensive sins as recounted in the books of Kings and Chronicles, Manasseh’s prayer reflects a profound transformation and sincere repentance. This penitential prayer is believed to have been composed during his captivity in Babylon, where he is said to have recognized the gravity of his transgressions and turned back to God with genuine remorse. The text captures the essence of his contrition and his desperate appeal for divine mercy.

The prayer begins with a grand acknowledgment of God’s omnipotence and righteousness, setting a tone of reverence and humility. Manasseh confesses his sins explicitly, detailing the ways in which he has defied God’s commandments and led his people astray. He speaks of his own unworthiness and the depth of his guilt, expressing an acute awareness of the just consequences of his actions. Yet, amidst this confession, there is also a fervent plea for forgiveness, rooted in the belief in God’s boundless compassion and willingness to pardon those who sincerely repent. This duality of confession and supplication forms the core of the prayer, illustrating a profound theological understanding of sin and redemption.

The Prayer of Manasseh culminates in an impassioned appeal for divine grace, emphasizing the transformative power of genuine repentance. Manasseh’s words reflect a deep longing for restoration and a renewed relationship with God, underscoring the theme of hope and renewal even in the face of profound wrongdoing. This text, though brief, offers a powerful insight into the nature of repentance and the enduring mercy of God. It serves as a timeless reminder of the possibility of redemption and the importance of turning back to God with a contrite heart. The Prayer of Manasseh enriches the Apocryphal literature with its moving portrayal of penitence and divine forgiveness, offering valuable spiritual lessons for believers across generations.

Psalm 151

Psalm 151, an intriguing addition to the Apocrypha, is a brief yet profound piece traditionally attributed to King David. This psalm stands apart from the canonical 150 psalms found in the Hebrew Bible, offering a personal reflection on David’s early life and his divine selection as king. The psalm begins with David recounting his humble beginnings as a shepherd boy, emphasizing his youth and insignificance in the eyes of his family. Despite his lowly status, David reflects on how God chose him over his more outwardly impressive brothers, highlighting the theme of divine election and the unexpected ways in which God’s favor manifests.

The latter part of Psalm 151 celebrates David’s victory over Goliath, a defining moment that exemplifies God’s power working through him. David attributes his success not to his own strength or skill, but to the divine intervention that guided his hand. This narrative serves to reinforce the central message of the psalm: that God’s will can elevate the humble and accomplish great things through the least likely individuals. Through its intimate and personal tone, Psalm 151 offers a unique glimpse into David’s sense of divine purpose and the profound humility that accompanied his rise to prominence. This psalm enriches the Apocryphal collection by providing an additional layer of insight into the character and faith of one of the most revered figures in biblical tradition, underscoring the enduring themes of divine grace and the power of faith.

Summary

The Apocrypha, a collection of ancient texts, occupies a unique and often debated position within the broader corpus of biblical literature. These writings, which include books like Tobit, Judith, the Maccabees, and the Wisdom of Solomon, are considered canonical by the Catholic and Orthodox churches but are excluded from the Hebrew Bible and many Protestant versions of the Old Testament. The Apocrypha offers a diverse array of genres and themes, from historical narratives and wisdom literature to apocalyptic visions and prayers. Despite their varied content, these texts share a common purpose: to provide theological insights, moral teachings, and reflections on the human experience in relation to the divine.

One of the central themes of the Apocrypha is the enduring faith and resilience of the Jewish people in the face of adversity. The Books of Maccabees, for instance, recount the heroic struggle for religious freedom against the oppressive Seleucid Empire, highlighting the themes of divine providence, martyrdom, and the quest for justice. Similarly, texts like Judith and Tobit emphasize the power of faith and prayer in overcoming personal and communal crises. These narratives not only celebrate the steadfastness of the Jewish community but also offer timeless lessons on the importance of piety, courage, and trust in God’s deliverance.

In addition to historical and narrative elements, the Apocrypha is rich in wisdom literature and theological discourse. The Wisdom of Solomon and Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) provide profound reflections on the nature of wisdom, righteousness, and the human condition, blending Jewish religious thought with Hellenistic philosophical influences. The prayers and hymns found in books like the Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews, as well as the Prayer of Manasseh, underscore the themes of repentance, divine mercy, and the transformative power of faith. Through its diverse texts, the Apocrypha enriches the biblical tradition with its multifaceted exploration of faith, morality, and the relationship between humanity and the divine, offering valuable insights and spiritual guidance that resonate across different religious traditions.