The book Dispensationalism: Essential Beliefs & Common Myths is a short-written work by Michael Vlach that explains Dispensational theology in terms of what it means to believe in it (i.e., essential beliefs) or its principles concerning its core features. It is also a defense of the theology as its adherents are aware of criticisms developed by its proponents. While the history of dispensationalism is traced in detail, the origination of its framework as a system of eschatological and ecclesiological belief comes from various influential figures in recent decades. Namely, John Nelson Darby, C.I. Scofield, and Charles Ryrie, among others, were primarily responsible for the advancement of dispensationalism as a way to understand the administration of covenants within eras of time that established linear rationale concerning end times. Considering that God’s whole counsel is exhaustive in terms of events (past, present, and future), dispensationalism suggests that there is a sensus plenior understanding from God’s perspective of what is to occur either descriptively or prescriptively.

To capture the available clarity of meaning and to understand how eschatological events unfold, the Scriptural basis of what the biblical writers conveyed is formed and traced where dispensationalists fit together historical periods toward future expectations—especially concerning the second coming and Christ’s presence on Earth during a millennial period. Dispensationalists do not accept the millennial period of eschatological concern situated in heaven (Rev 20:1-5). Among the several essential beliefs that Vlach outlines, he clarifies that dispensationalism includes a “future earthly millennial kingdom”.

Essentials

As Dr. Vlach informs his readers about the essential beliefs of dispensationalism, he does so with precision to explain the views and positions of dispensationalists. While I do not know enough about the claims and assertions of dispensationalists, I only offer this review to understand what it is and how it compares to its rival in the form of Covenant Theology. Dr. Vlach presents several points about what is at the heart of dispensationalism.1 Among them, there are key points of interest about the framework to include:

- The literal meaning of the Old Testament as interpreted by original authorial intent and the meaning of a passage is retained in its plain reading

- Israel’s status as a nation and distinct people of God is not superseded

- The church doesn’t replace Israel to assume its identity as a new Israel

- Jews and Gentiles alike are in spiritual unity concerning salvation while Israel remains a future nation

- A future earthly kingdom includes a redeemed and restored nation of Israel and will attain a functional role unique to it as a people

- The “seed of Abraham” promises include both Israel of the Old and New Covenants and the Church of the New Covenant – both are not mutually exclusive as the “seed of Abraham” as the phrase applies to both Jews and Gentiles

A careful review of these points appears to rest upon Israel as a nation during the church age and its eschatological role and status according to the literal interpretation of Scripture. According to Vlach, these are essential beliefs at the heart of dispensationalism. Each point is covered at length to explain their contribution to the correct understanding of dispensationalism. These are core principles to grasp and accept as a believer in the dispensational framework and further understand dispensations along a linear timeline of redemptive history. To firmly understand the meaning and implications of dispensationalism, each of these critical points within the outline must hold throughout the interpretive analysis of the system. To get a more explicit definition that describes the term “dispensationalism,” it is helpful to consult a dictionary for clarity of understanding.

As Dr. Vlach makes further efforts to identify the myths surrounding dispensationalism, he identifies with explicit detail, including citations, misconceptions about what it is, and what theological commitments are necessary to accept the system as valid. First, a handbook definition of the “dispensationalism” term is fitting:

Dispensationalism: “A system of theology popularized mainly in twentieth-century North America, especially through the influence of the Scofield Reference Bible. The dispensationalism delineated by Scofield suggested that God works with humans in distinct ways (dispensations) through history; that God has a distinct plan for Israel over against the church; that the Bible, especially predictive prophecy, needs to be interpreted literally; that the church will be secretly raptured from earth seven years prior to Christ’s second coming; and that Christ will rule with Israel during a literal thousand-year earthly reign. Contemporary, or progressive, dispensationalism remains thoroughly premillennial but rejects the ontological distinction between Israel and the church as two peoples of God, seeing them instead as two salvation-historical embodiments of a single people.”2

A noticeably different definition compared to how Dr. Vlach defined the term:

Dispensationalism: “A system of theology primarily concerned with the doctrines of ecclesiology and eschatology that emphasizes applying historical-grammatical hermeneutics to all passages of Scripture (including the entire Old Testament). It affirms a distinction between Israel and the church, and a future salvation and restoration of the nation Israel in a future earthly kingdom under Jesus the Messiah as the basis for a worldwide kingdom that brings blessings to all nations.“3

Myths

As further consideration is given to the points about dispensationalism, Dr. Vlach writes about several myths concerning the theological framework. From descriptions about what it is to what dispensationalism is not specifically. Dr. Vlach offers responses to counter assertions by those opposed to dispensationalism. Or at least segments of the theology as it developed from the 20th century onward. Several myths were identified to refute people’s objections to individual tenets of dispensationalism. Objection claims were substantiated by numerous citations serving as a collection of valuable references upon which the pioneers of dispensationalism stood. To Dr. Vlach’s credit, he cites journal articles and monographs that articulate the specific objections from well-known and credible scholars, academics, and church leaders as each objection is named and described, interacting around the specifics in defense of dispensationalism. The objections Dr. Vlach sought to discredit include the following:

- Soteriology: Dispensationalism infers multiple paths to Salvation

- Synergism: Dispensationalism is linked to Arminianism

- Ethics and Morality: Dispensationalism is linked to Antinomianism

- Faith and Practice: Dispensationalism eventually falls into Non-lordship Salvation

- Theology: Dispensationalism is chiefly about several dispensational eras

These came from multiple sources, and there was a period when the proponents of dispensationalism were in rigorous defense of theology more recently advocated and supported within the 20th century.

Continuity & Discontinuity

The book continues with the section entitled, Continuity and Discontinuity in Dispensationalism. While Dr. Vlach acknowledges a discontinuity that appears between eras of time, he also stresses there are points of continuity throughout redemptive history. First, about the storyline of the Old Testament and the fulfillment of Christ’s coming at the beginning and end of the church age. The presence of the Kingdom of God on Earth with the Messiah, Israel, and its status, role, and land among the nations, the salvific work accomplished among believing Gentiles, salvation by grace through faith alone, the Day of the Lord, and the use of the Old Testament from the New together constitute areas of continuity within dispensationalism. Interestingly, Vlach writes of eight areas of continuity interwoven throughout redemptive history yet does not include the various covenants.

There are also various areas of discontinuity acknowledged within dispensationalism. Namely, Israel and the church, the Mosaic covenant to the new covenant, dispensations (eras of administrative time), the people of God, and the role of the Holy Spirit are individually listed as points of discontinuity. These points of discontinuity are not stops and starts along their presence throughout history. Instead, each instance of discontinuity arrives at points in time as sequenced by linear arrival. As a rebuttal or balance to the notion of change and disconnect as transitions happen from one dispensation to another, there is a transition of states countered by periods, events, or conditions of continuity. John S. Feinberg’s “Systems of Discontinuity,” in his work Continuity and Discontinuity: Perspectives on the Relationship Between the Old and New Testaments (Crossway, 1988), identified dispensationalism as a discontinuity system because of the distinction between Israel and the church.

Rather than blur the lines of distinction between Israel and the church, a system of discontinuity is stood up to preserve Israel’s unique status and role. In comparison to the dismissal or absence of distinction in correlation to the arrival of the Kingdom of God on Earth through the Messiah of Jews and Gentiles, a principle of continuity is set in place alongside Feinberg’s observations about a discontinuous system as dispensationalism. What appears as an effort to preserve Israel as a protective measure of a separate people (c.f. The Jerusalem Council of Acts 15), disparate continuous and discontinuous parsing of time is set as a governing framework of what occurs as an administrative structure along God’s sovereignty. God’s plan dispensationalists cast or follow in this way honor God’s historically unique people of Israel.

As social gospel advocates or the church itself at times historically leverages soteriological imperatives around salvation attained by faith and ecclesiological efforts, the system of dispensationalism is suspect as a manner in which biblical principles and storylines are leveraged to preserve Israel’s role and status before God and throughout humanity. While Israel’s unique and permanent role and status are accurate and correct throughout redemptive history and eschatological prophecy, the use of Scripture to form continuous and discontinuous systems must withstand high levels of scrutiny as a matter of exegetical integrity. For example, Paul’s letter to Timothy about “rightly dividing” the word of truth in 2 Timothy 2:15 doesn’t, in context, appear to be informing readers about eras of discontinuity. Instead, Paul’s message to Timothy was about properly handling Scripture as the word of truth to function as a worker who honorably resolves disputes as approved by God.

To draw comparisons between covenant and dispensational theology, Dr. Vlach makes an excellent point that both perspectives recognize the weight of meaning within Hebrews 1:1-2.

“Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world.” – Hebrews 1:1-2

To highlight the actual means and differences to which God has verbally expressed His intentions and interests, there are distinctions inherent in “at many times and in many ways” that calls attention to the authority of His Word. The term “Polymerōs” translates to “at many times,” defined as “in many parts” with “Polytropōs” as “many ways.”4 The Greek translation, in this sense, indicates many portions or allotments by which God speaks as a manner of revelation to accomplish His purposes and objectives.

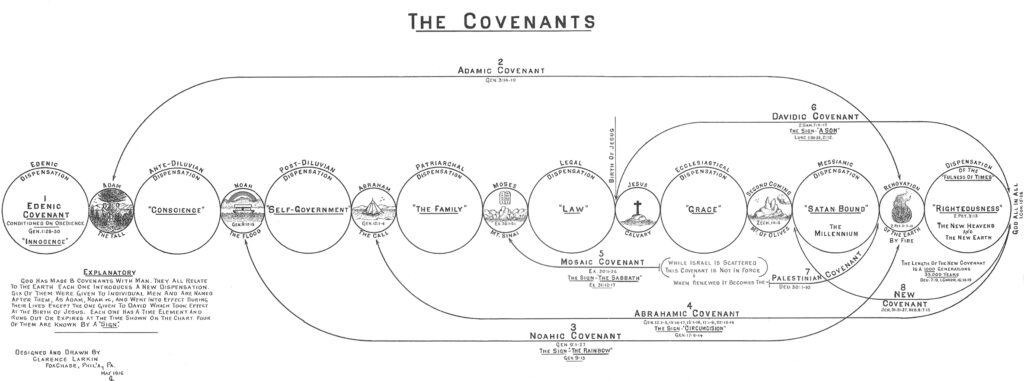

Furthermore, Dr. Vlach makes clear, in his view, that biblical hermeneutics and storyline are the most fundamental differences between covenant and dispensation theology. While both covenantalists and dispensationalists affirm various covenants through redemptive history, there are three that covenant theology generally views as most important. In contrast to the covenants identified by Clarence Larkin (1850-1924), a dispensationalist, the three overarching covenants of covenant theology recognized as the “covenant of redemption,” the “covenant of works,” and the “covenant of grace” sometimes distill down to covenants of works and grace. Clarence Larkin’s covenants, according to his “The Covenants” illustration, there are eight covenants as follows: 5

- Edenic Covenant

- Adamic Covenant

- Noahic Covenant

- Abrahamic Covenant

- Mosaic Covenant

- Davidic Covenant

- Palestinian Covenant

- New Covenant

Figure: Covenants of “Dispensational Truth, by Clarence Larkin.

Covenants interspersed among various dispensations in accordance with the dispensation theology of the 20th century.

Citations

____________________

1 Vlach, Michael. Dispensationalism: Essential Beliefs and Common Myths: Revised and Updated (p. 31). Theological Studies Press. Kindle Edition.

2 Stanley Grenz, David Guretzki, and Cherith Fee Nordling, Pocket Dictionary of Theological Terms (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1999), 39–40.

3 Vlach, Michael. Dispensationalism: Essential Beliefs and Common Myths: Revised and Updated (p. 93). Theological Studies Press. Kindle Edition.

4 William Arndt et al., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 847.

5 Clarence Larkin, Dispensational Truth, or “God’s Plan and Purpose in the Ages: Charts“ (Philadelphia, PA: Clarence Larkin, 1918).