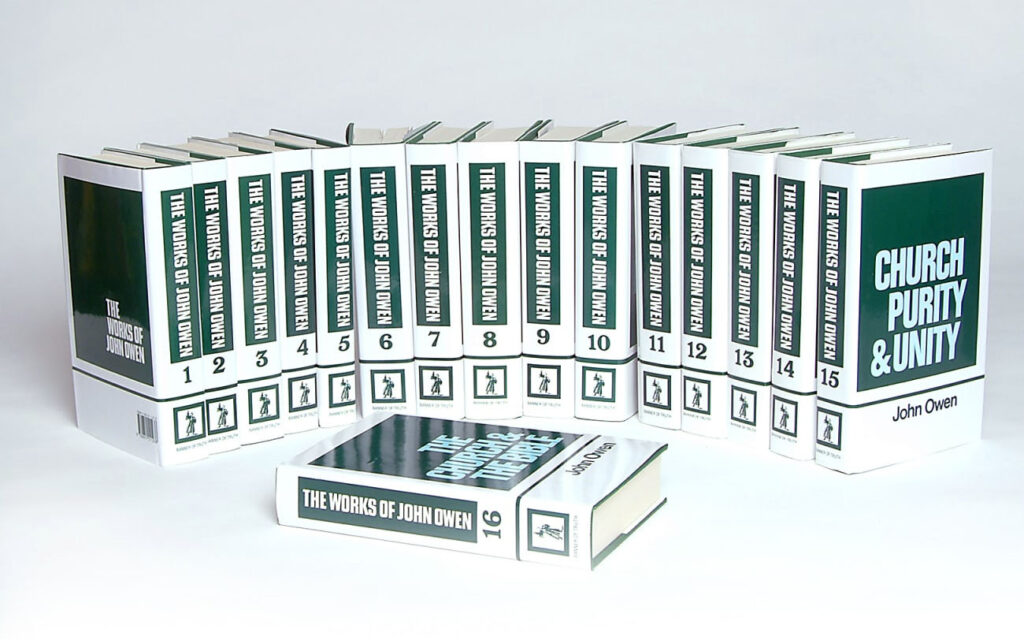

For quite a long time, I’ve had an abridged version of John Owen’s The Mortification of Sin published by Banner of Truth. Its length is only about 130 pages, and it spans 14 short chapters, just like the unabridged version. However, it was written in significantly different prose to retain thoughts throughout the structural layout and format of the book. As it was so different and written this way as “easy to read” (as indicated by its cover), the editor (Richard Rushing) updated John Owen’s old English literary expression to modern terms and phrases. The text changes went quite a bit further than that compared to Owen’s written work. So, I turned my attention to the unabridged version and went through that until completion. The written copy I have is from The Works of John Owen Volume 6 of 16, part 1 (“The Mortification of Sin in Believers”).1 John Owen wrote this treatise on killing sin many years before this publication date of 1862, but the subject matter was carried forward differently and directly for a more thorough understanding.

While this book section, The Mortification of Sin in Believers, is short, it is highly dense in meaning and urgency. This first pass was an effort to clear through the book (section 1 of volume 6) without analyzing or stopping time to dwell upon anything. The overall effort was to get the message and meaning as a read-through about a Puritan’s perspective concerning what the Apostle Paul wrote to the churches in Rome and Colossae. Specifically, the 17th-century puritan was highly concerned about the presence of sin in the lives of believers, and he wrote a widely read examination of what putting sin to death looks like. While the mortification of sin was John Owen’s pressing concern, he offered encouragement, exhortation, clarity, and guidance to understand what sin is and does. He had specific thoughts about what it is to eradicate its root by the Spirit and the involvement of the believer’s intentional will.

“For if ye live after the flesh, ye shall die: but if ye through the Spirit do mortify the deeds of the body, ye shall live.” – Romans 8:13 KJV

“Mortify therefore your members which are upon the earth; fornication, uncleanness, inordinate affection, evil concupiscence, and covetousness, which is idolatry: For which things’ sake the wrath of God cometh on the children of disobedience.” – Colossians 3:5-6 KJV

This is not a book that is simply readable once as a pass-through without much contemplation and self-reflection. Sin is so grave that it eternally damns people, according to scripture. Owen, just as Paul did, wrote of “mortifying” it. As mortification is an old English translation rendering, it corresponds to “putting to death” among modern translations (ESV, NIV, NKJV, HCSB, and more). The term “mortify” is translated the same in both references in Romans 8:13 and Colossians 3:5, while their Greek root terms are different.

Furthermore, mortification, or mortify, is understood from multiple perspectives, all consistent in meaning. “The act of self-denial or the “putting to death” of sinful instincts or cravings in order to have freedom from sin and to live in the power of the Holy Spirit. The NT stresses that this act of humiliation comes about through the grace of God. It is the result of, not the condition for, conversion.” The key passages Paul wrote correspond to numerous principles Owen stressed as they together support the Reformed tradition.

Mortification:

The process of “putting to death” one’s sinful nature as the old self, which continually struggles because of the reality of indwelling sin. This process takes place in the lives of believers who, while they have been set free from sin’s dominion by the indwelling Holy Spirit who unites them to Christ, are called to live in light of God’s grace as they actively work out their salvation. …. if it is truly part of sanctification, it must be accomplished through the Spirit of Christ in dynamic interplay with a believer’s response of repentance; mere human effort does not result in increased freedom from sin, even if it changes outward behavior.2

To Owen’s point in his book, while a person could successfully overcome sinful behaviors, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the instincts and cravings were put to death. Compared to Reformed theology, Catholicism also emphasizes Galatians 5:24, where it is necessary to “crucify the flesh.”3 As some English translations render “consider as dead” (NASB, LSB) in a passive sense, many other translations (including various Catholic translations) are active with the “put to death” language. For example, the “Little Rock Catholic Study Bible,” “New American Bible: Revised Edition” (NABRE), “The Revised Standard Version, Catholic Edition” (RSVCE), “Douay-Rheims Bible” as mortify (D-R), and the “Ignatius Bible: Revised Standard Version, Second Catholic Edition” (RSV2CE) all express the same meaning. When delving further into the definition of the terms nekroō (νεκρόω) in Colossians 3:5 and thanatoō (θανατόω) in Romans 8:13, they both correlate to the “put to death” sense of meaning. The Louw-Nida Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament ties both terms together as figurative in suggestive meaning where intended readers understood the original root manuscripts as conventional figures of speech to communicate the same idea.4

Owen is clear in his book that mortification is not a passive posture of sin in the flesh as mere recognition or consideration from a believer. He stresses that it is an active conscious effort of someone as a converted person who became a believer by faith and repentance. However, he also recognizes that the process of mortification is lifelong, and it depends solely upon the Spirit of Christ to definitively accomplish the continued crucifixion of sin in the life of a believer. The believer is participative by necessity but is not the practical and final means of mortification. The Spirit of Christ is who does the work. As sin was put to death in the sacrifice and resurrection of Christ Jesus, the law of death is applied to sin itself in the lives of believers. Where there Spirit lives within believers, there is the law of life by the Spirit as long as there is no yield to sin. That sin is persistently, iteratively, and ruthlessly killed actively about particular offenses. Mortification is “the slaying of the disease of the soul, and by slaying this disease, it restores and invigorates the soul’s true life.” 5

To further give careful thought about directions, general rules, assertions, means, and the heart, it is of salvific concern to camp on Owen’s written views as supported by scripture. He doesn’t attempt to assign weight to tradition or works of the law. Still, that mortification of the flesh is an intentional effort of faith, necessary to sanctify believers who work out their salvation with fear and trembling (Phil 2:12-13). As it is impossible to earn salvation through works or efforts that yield positive outcomes and the removal of sins, if efforts of mortification are not by faith, they are of no spiritual value. Owen asserts that such progress involves the replacement of sins with others in the absence of necessary faith through the heart of a believer concerning the treacherous and destructive nature of sin. Under the authority of God’s Word as written by the Holy Spirit through the Apostle Paul, those who live by the flesh will die. In contrast, those who live by the Spirit shall live. To be more explicit, regarding the term “flesh” (Rom 8:13 KJV), John Chrysostom (347 – 407 A.D., Archbishop of Constantinople) refers to it as follows: “what Paul means by the flesh in this passage is not the essence of the body but a life which is carnal and worldly, serving self-indulgence and extravagance to the full.” 6

Owen’s readers might also remember Jesus’s parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). And specifically, verse 25: “But Abraham said, ‘Child, remember that you in your lifetime received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner bad things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in anguish (see Luke 6:24; Job 21:13; Ps. 17:14). The comparative man who fared “sumptuously” (Luke 16:19) was condemned. Where the rich man in the parable was delighted, glad, and enjoying himself in celebration and rejoicing by dining and merriment, there was apparent opulence that highlighted the disparity between him and Lazarus.

While this is a short book review on the unabridged version of The Mortification of Sin, it is about the abridged version from Banner of Truth Trust and the more comprehensive version in volume 6 from T&T Clark as part of the sixteen-volume set published in 1862 (MDCCCLXII). The first pass through the book is insufficient for a reader to grasp the necessary points of study and understand the subject matter. A surface reading to get a topical understanding of what Owen wrote doesn’t support the best in terms of retention and application. To more fully grasp what Owen wrote here concerning the killing of sin is a weighty subject. Whether a reader’s immersion in the text is through the abridged or unabridged version, this is a book to iterate upon. My first time through this book thoroughly informed me about why John Owen is so widely read and studied. Nevertheless, his pressing concern about the lifelong urgency of killing sin within is not a daily call to repentance but a persistent and ruthless inward campaign to find and destroy anything innate that raises itself against God and the Spirit of Christ.

Citations

___________________________________________

1 John Owen, The Works of John Owen, ed. William H. Goold, vol. 6 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, n.d., 1862).

2 Kelly M. Kapic and Wesley Vander Lugt, Pocket Dictionary of the Reformed Tradition, The IVP Pocket Reference Series (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2013), 76.

3 Charles G. Herbermann, Edward A. Pace, et al., eds., “Mortification,” The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church (New York: The Encyclopedia Press; The Universal Knowledge Foundation, 1907–1913).

4 Johannes P. Louw and Eugene Albert Nida, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains (New York: United Bible Societies, 1996), 660.

5 Ibid. Herbermann.

6 John Chrysostom, “Homilies of St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, on the Epistle of St. Paul to the Romans,” in Saint Chrysostom: Homilies on the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistle to the Romans, ed. Philip Schaff, trans. J. B. Morris, W. H. Simcox, and George B. Stevens, vol. 11, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1889), 434–435.