Today, I completed reading St. Athanasius’s On the Incarnation to understand the meaning of Theosis, or Union with Christ. This writing from St. Athanasius of Alexandria is a masterpiece of early Christian theology, offering a deep reflection on the central mystery of the Christian faith: the Word of God becoming flesh. Written in the 4th century, this treatise provides a clear and compelling explanation of why the Incarnation of Christ was necessary and how it accomplished the salvation of humanity. For Athanasius, the Incarnation is a historical event and a necessary point along God’s redemptive plan. He took on human nature to heal, restore, and elevate it. Christ united God and humanity by becoming man, opening the way for believers to share in the divine life (2 Peter 1:4).

Introduction

Athanasius anchors his argument in the doctrine of theosis, the idea that humanity is called to participate in the divine nature. He famously summarizes this profound truth with the statement, “God became man so that man might become god.” In his view, humanity’s original purpose was to live in communion with God, reflecting His image and likeness. However, sin disrupted this union, plunging humanity into corruption and death. Through the Incarnation, Christ reversed this tragic trajectory. By taking on human flesh, He sanctified it, defeating death through His death and resurrection. In doing so, He restored humanity’s capacity to become like God—not in essence, but by grace (energia) through union with Him.

On the Incarnation offers more than just theological insight; it presents a vision of the Christian life as a transformative journey. The Incarnation is not merely an abstract theological concept but the foundation of a believer’s hope. Through Christ’s assumption of human nature, every person is invited to participate in His divine life. This process, known as theosis, is both a gift and a calling, requiring the believer’s active response in faith, repentance, and love. For Athanasius, the Incarnation is the ultimate demonstration of God’s love, revealing a Creator so committed to His creation that He became one with it to redeem and glorify it. In these pages, readers find a defense of the Christian faith and an invitation to experience its transformative power.

Preface: C.S. Lewis’s Perspectives

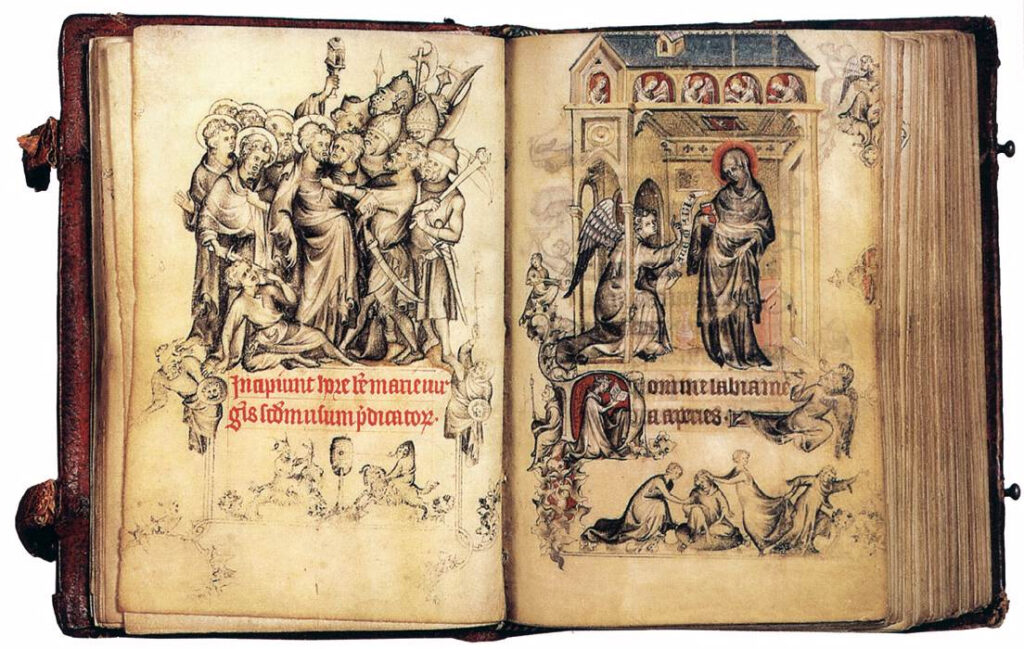

C.S. Lewis’s book preface highlights the timeless value of reading classical theological works, particularly those of the Church Fathers. He reasons that modern Christians rely too heavily on contemporary authors, who are shaped by the same cultural and intellectual limitations as their readers. Lewis emphasizes that reading “old books” provides a broader and more balanced perspective, allowing readers to encounter ideas untainted by the biases of the modern era. He praises On the Incarnation for its clarity and depth, describing it as a work that addresses universal truths of the Christian faith without being bogged down by later theological controversies or denominational divisions. For Lewis, St. Athanasius offers an unfiltered glimpse into the early Church’s understanding of the Incarnation, providing modern readers with spiritual nourishment and doctrinal stability.

Lewis also reflects on the accessibility of Athanasius’ writing, noting its simplicity and directness despite addressing profound theological topics. He acknowledges that some readers might initially find the ancient style challenging but assures them that perseverance will reward them with a richer understanding of the Christian faith. The preface concludes with a call to engage directly with primary sources like Athanasius’ work rather than relying solely on secondary interpretations. Lewis sees On the Incarnation as an essential read for any Christian seeking to understand the mystery of the Word made flesh and its implications for faith and life. Through his preface, Lewis not only endorses the work but also encourages readers to cultivate a habit of learning from the foundational writings of Christianity.

Introduction: John Behr’s Perspectives

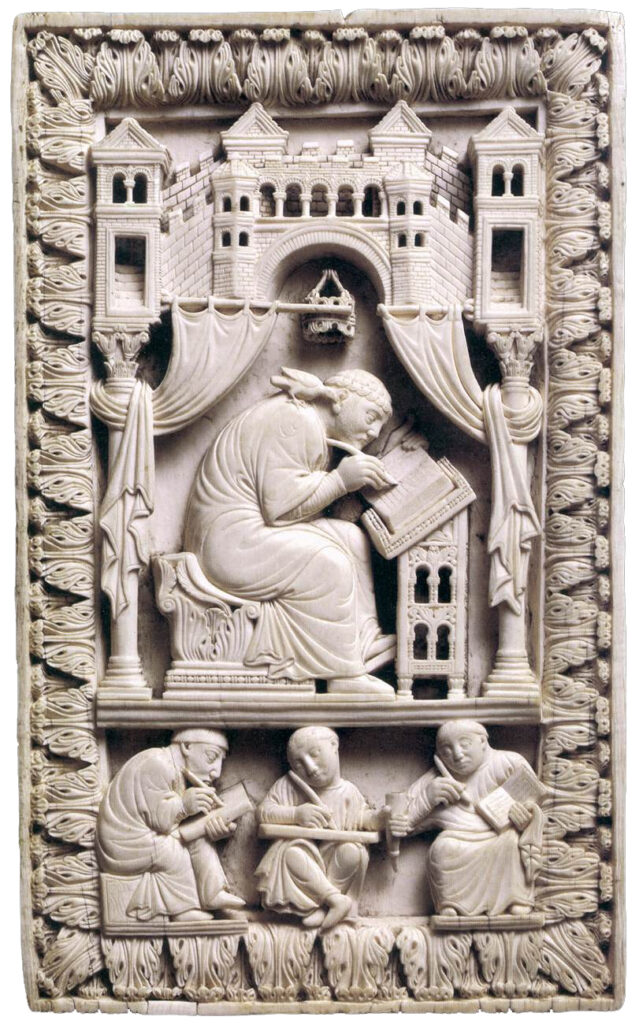

In his background profile of St. Athanasius, Behr presents Athanasius as one of the most influential figures in early Christianity, revered for his theological brilliance and unwavering defense of orthodox doctrine. Born in the late 3rd century and serving as Bishop of Alexandria during a tumultuous period, Athanasius is best known for his unwavering opposition to Arianism, which denied the full divinity of Christ. Behr highlights Athanasius’ role at the First Council of Nicaea (325 AD), where he championed the Nicene Creed, affirming the Son as “of one essence with the Father.” Despite enduring repeated exiles and political opposition, Athanasius remained steadfast in his commitment to preserving the faith of the Church. His writings, particularly On the Incarnation, reflect his profound theological insight, emphasizing the unity of creation, redemption, and humanity’s call to theosis through Christ. Behr underscores Athanasius’ enduring legacy as a defender of truth and a central figure in shaping Christian dogma and theology.

Against the Gentiles

In his analysis of Against the Gentiles, Behr emphasizes its foundational role in St. Athanasius’ theological framework, presenting the Incarnation as the ultimate answer to humanity’s search for truth. Behr highlights Athanasius’ critique of paganism, arguing that idolatry and polytheism are corruptions of humanity’s innate knowledge of God, rooted in creation. According to Athanasius, failing to honor the Creator leads to moral decay and a false understanding of reality. Behr notes how Athanasius systematically demonstrates that the Incarnation restores humanity’s capacity to know God by revealing the divine Logos, who created and redeems the world. This work sets the stage for On the Incarnation, where Athanasius expands upon the divine remedy for human corruption through Christ. Behr emphasizes how Against the Gentiles and On the Incarnation form a cohesive apologetic and theological argument, establishing Athanasius as a profound defender of Christian truth.

On the Incarnation

Behr further delves into what is termed “the apology of the cross,” presenting it as a profound theological defense of the Incarnation and crucifixion. Behr explains that Athanasius views the cross not merely as an instrument of death but as a demonstration of divine wisdom and power. The crucifixion, in this light, is an apology or a defense, showing that what appears as weakness or defeat is, in reality, the ultimate victory over death and sin. This perspective reframes the narrative of the cross from one of humiliation to one of divine triumph, where Christ’s voluntary submission to death reveals the depth of God’s love and His sovereignty over all creation, including death itself.

Behr also explores Athanasius’s view of the divine works of Christ, which are central to understanding the purpose of the Incarnation. Athanasius argues that Christ accomplishes the renewal of human nature through His divine works. The Incarnation is seen as God’s intimate involvement in humanity’s existence, where Christ sanctifies it by taking on human flesh. This act of becoming human allows Christ to heal the corruption caused by sin from within humanity itself, offering a path to Theosis, where humans can partake in the divine life.

The divine predicament, as Behr interprets Athanasius, involves the necessity for God to reconcile humanity to Himself in a way that esteems humanity as image bearers, which the Incarnation and the works of Christ recover and preserve. The divine predicament was to challenge how a just God can forgive sin without undermining His justice or the integrity of the moral order He created. Through his apology of the cross, Athanasius provides a solution where God, in Christ, becomes subject to death, thus defeating it from the inside. This act of divine self-giving not only satisfies justice but also demonstrates love, thereby resolving the divine predicament by fulfilling the Law, defeating death, and making it possible for humans to be reconciled with God. Behr stresses that this view transforms our understanding of God’s interaction with the world, emphasizing that the divine works of Christ are not merely about retribution for sin but about the restoration and elevation of human nature to divine union.

In the second part of “The Divine Dilemma,” the Incarnation resolves humanity’s plight of corruption and death. Athanasius identifies a divine “dilemma”: how could God remain true to His justice, which demands the consequences of sin (death), while also fulfilling His love for humanity by restoring it to life? Behr highlights Athanasius’ answer that the Word of God, through His Incarnation, addresses this dilemma by taking on human nature and offering Himself as a perfect sacrifice. Through His death on the cross, Christ fulfills the demands of justice by bearing the penalty of sin, while simultaneously manifesting the love of God by defeating death and restoring humanity to its intended state of immortality. Behr underscores how Athanasius integrates creation, fall, and redemption into a cohesive vision, where the Incarnation is not merely a response to sin but the ultimate expression of God’s eternal purpose for humanity: union with Him through theosis.

In his discussion of the second part of “The Divine Dilemma,” Behr further emphasizes St. Athanasius’ insight into how God’s wisdom intimately connects the Passion to the Incarnation. Behr explains that Athanasius views the Word’s taking on flesh as inherently tied to His suffering and death, which were not incidental but essential to God’s plan for the restoration of humanity. Through the Passion, the Word fulfills the demands of justice by taking upon Himself the penalty of human sin, while His Incarnation ensures that this act of self-offering is both divine and universal in its redemptive scope. Behr highlights how Athanasius frames the Passion as the culmination of the Incarnation, demonstrating God’s wisdom in addressing humanity’s corruption not through mere power but by entering fully into human frailty to heal and transform it from within. This profound connection reveals the Incarnation and the Passion as two inseparable aspects of God’s salvific plan, showing the unity of divine justice and love in the person of Christ.

The Life of Anthony

Saint Anthony’s ascetic life reflects the theological significance of the Incarnation, particularly concerning the preservation and sustainment of the body. Behr emphasizes that for Athanasius, Antony’s life demonstrates the transformative power of Christ’s Incarnation, as Antony’s discipline and holiness exemplify humanity’s restoration through Christ. Antony’s ascetic practices, centered on prayer, fasting, and solitude, reveal a life fully aligned with the divine, showcasing how the body—once subject to corruption—is preserved and sustained by participation in the life of the Incarnate Word. Behr points out that Antony’s triumph over bodily passions and the frailties of the flesh is a direct result of Christ’s victory over death and corruption, which Athanasius attributes to the Incarnation’s sanctification of human nature.

Behr further connects Antony’s life to the theological framework of On the Incarnation, showing how the saint’s asceticism serves as a practical witness to the Word’s transformative work in creation. Through the Incarnation, Christ not only redeems the soul but also renews the body, enabling it to partake in divine life. Anthony’s 20-year-long spiritual struggles in the desert, particularly against demonic forces, highlight the reality of this renewal, as his purified body becomes a vessel of divine strength and grace. Behr argues that Anthony’s ability to sustain himself with minimal physical nourishment and his resilience against physical temptations underscore the Incarnation’s power to preserve and uplift the body as part of God’s redemptive plan. Anthony’s life thus serves as a concrete example of the potential for human beings to live in harmony with the divine image, overcoming the effects of sin and corruption.

In conclusion, Behr presents Anthony’s life as a profound testimony to the Incarnation’s impact on the whole person—body and soul—illustrating the Word’s restorative work in creation. The preservation and sustainment of Anthony’s body through divine grace point to the Incarnation’s purpose of uniting humanity with God, not only spiritually but physically as well. Antony’s ascetic practices, far from being mere personal piety, reveal the universal truth that through Christ’s Incarnation, death, and resurrection, the human body is no longer bound by corruption but is sustained and preserved by divine life. Behr highlights that The Life of Antony offers readers an invitation to reflect on their own lives in light of the Incarnation, encouraging them to seek the transformation of their entire being through the life-giving power of the Word made flesh.

Dilemma: Life and Death

St. Athanasius’s discourse about the Divine Dilemma regarding Life and Death focuses on humanity’s fall into corruption and God’s response through the Incarnation. Athanasius begins by explaining that humanity was created in the image of God, intended for eternal communion with Him. However, through sin, humanity chose disobedience, leading to separation from God, spiritual corruption, and the inevitability of death. Athanasius frames the dilemma: God’s justice required that humanity face the consequences of sin (death), yet His goodness and love could not allow His creation to perish entirely. This tension between justice and mercy sets the stage for the divine solution: the Word of God taking on flesh to restore humanity and defeat death.

Athanasius explains that only the Incarnation could resolve this dilemma. The Word, who created humanity, enters creation to renew it from within. By assuming human nature, the Word sanctifies it, reversing the corruption brought about by sin. In His death on the cross, Christ fulfills the demands of justice by taking the penalty of death upon Himself, while simultaneously manifesting God’s love by offering humanity a path back to life. Athanasius emphasizes that this act is not arbitrary but reflects God’s wisdom: the divine Word, as both fully God and fully human, bridges the gap between mortal humanity and the immortal God. Through His resurrection, Christ destroys the power of death, offering all who are united with Him a share in His victory and the promise of eternal life.

In conclusion, St. Athanasius presents the Divine Dilemma as a profound revelation of God’s character, where justice and mercy are perfectly united in the Incarnation. The solution to the dilemma—the Word made flesh—demonstrates God’s commitment to His creation and His desire to restore humanity to its original purpose: life in communion with Him. Athanasius’ exploration of life and death in this context provides a theological foundation for understanding salvation, showing that through Christ’s Incarnation, death, and resurrection, the human condition is transformed, and the way to eternal life is opened. This teaching remains a cornerstone of Christian soteriology, illustrating the depth of God’s love and the profound significance of the Incarnation.

Dilemma: Knowledge and Ignorance

St. Athanasius addresses the Divine Dilemma regarding Knowledge and Ignorance, focusing on humanity’s loss of the knowledge of God due to sin and the Incarnation as God’s solution to restore it. Athanasius begins by explaining that humanity was created with the capacity to know God, as bearers of His image. This knowledge was meant to be nurtured through communion with Him. However, through sin, humanity turned away from God, resulting in spiritual ignorance and idolatry. Instead of perceiving God through creation, humans began to worship the creation itself, falling into error and losing sight of their Creator. This ignorance not only distorted their understanding of God but also led to moral and spiritual corruption, alienating humanity further from the divine purpose.

Athanasius argues that the Incarnation was necessary to resolve this dilemma and restore humanity’s knowledge of God. While God had revealed Himself through the Law, the prophets, and creation, these means were insufficient to overcome humanity’s ignorance. Therefore, the Word of God took on flesh and entered creation so that humanity could once again recognize and know Him. By assuming human form, Christ made the invisible God visible and accessible to all. Athanasius emphasizes that the Incarnation provides a direct and tangible revelation of God’s character, will, and purpose. Through His teachings, miracles, and ultimate sacrifice, Christ not only revealed the truth about God but also demonstrated God’s profound love for humanity.

In conclusion, Athanasius presents this Divine Dilemma regarding Knowledge and Ignorance as a fundamental aspect of humanity’s fall and redemption. The Incarnation resolves this dilemma by re-establishing the relationship between Creator and creation, enabling humanity to rediscover the true knowledge of God. Through Christ, Athanasius argues, humanity is restored to its original purpose, empowered to know and worship God as intended. This renewal of knowledge transforms not only the intellect but also the heart and soul, leading believers back to the divine life for which they were created. Athanasius’ reflections on this dilemma underscore the Incarnation’s pivotal role in overcoming humanity’s estrangement from God and restoring the fullness of divine truth.

Death and Resurrection

St. Athanasius presents the Death and Resurrection of the Body as central to God’s plan of salvation, achieved through the Incarnation of the Word. Athanasius begins by addressing the problem of death, which entered the world through humanity’s sin and disobedience. Created in the image of God and intended for immortality, humanity’s turning away from God led to separation from the source of life, resulting in corruption and physical death. Athanasius emphasizes that death was not part of God’s original plan but a consequence of humanity’s fall, necessitating divine intervention to restore life. The Word’s taking on of human flesh was the means by which God could directly confront death and overcome it from within.

Athanasius explains that through His death on the cross, Christ defeated the power of death, fulfilling the demands of justice and nullifying death’s hold on humanity. By willingly entering death, the Word transformed it into a gateway to eternal life. Athanasius underscores that Christ’s resurrection is not merely a miraculous event but the definitive act that restores the body and soul to their intended harmony. The resurrection of Christ’s body is both the proof and the firstfruits of the universal resurrection, guaranteeing that those united with Him will also rise to eternal life. Athanasius highlights that the Incarnation was essential for this victory, as only the Word made flesh could redeem human nature and conquer death.

Finally, St. Athanasius portrays the Death and Resurrection of the Body as the culmination of the Incarnation’s salvific purpose. By taking on a mortal body, Christ sanctified human nature and reversed the effects of sin and death. His resurrection ensures the eventual resurrection of all believers, restoring the body to its original dignity and purpose in communion with God. Athanasius’ teaching on this subject underscores the transformative power of the Incarnation and its implications for both individual and cosmic redemption. Through the death and resurrection of Christ, the ultimate enemy—death itself—is defeated, and the hope of eternal life is secured for all who participate in the life of the Incarnate Word.

Conclusion

On the Incarnation by St. Athanasius is a theological masterpiece that presents a profound explanation of the mystery of the Word made flesh. Written in the 4th century, this immensely important work defends the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation as the cornerstone of Christology as a necessary dogma for biblical belief. Athanasius begins by addressing humanity’s fall into sin and its devastating consequences—corruption, ignorance, and death. He explains that humanity, created in the image of God and meant for eternal communion with Him, had turned away from the Creator, forfeiting its intended purpose. The Incarnation, Athanasius reasons, is God’s ultimate response to this crisis: the Word of God takes on human nature, entering creation to heal, restore, and elevate it. By assuming flesh, Christ sanctifies humanity, overcomes death through His own death, and opens the way for humanity to participate in the divine life.

Athanasius also emphasizes the cosmic and universal scope of the Incarnation. He presents it as not only a remedy for sin but also a renewal of creation itself, revealing the love, wisdom, and justice of God. Through His life, death, and resurrection, Christ reveals God’s character, defeats the power of sin and death, and restores humanity’s ability to know and worship God rightly. Athanasius portrays the Incarnation as the ultimate demonstration of God’s justice, fulfilling the demands of divine law, and His mercy, offering salvation to all. The book’s enduring appeal lies in its theological clarity, spiritual depth, and relevance to the Christian life, as it portrays the Incarnation as the pivotal act through which God reconciles and transforms creation, inviting humanity into eternal communion with Him.