This post examines how Puritans of the 17th-century thought and wrote about the biblical topics of sin and repentance. As this topic is explored from historical writings of well-known Puritans of their time, various additional perspectives from numerous sources also come into view. While the views and writings of Puritans Thomas Watson and John Owen are central to this post, their convictions about sin and repentance are of tremendous significance. Their teachings, lectures, sermons, and literary work are voluminous as these two men devoted themselves to God, family, and ministry. They shared a deep and abiding concern for the human condition as people separated from God by their sin were cause for alarm.

Introduction

Historically, the Puritans of England were a people who were protestant in faith with a biblically-centered view of life, faith, and practice. They were of the Reformed heritage of belief and confession, which had a bearing on their lifestyle, worship, faith, and practice. As people who sought and lived simple lives, they were an interconnected community of believers who valued education as they lived with a strong work ethic. Watson and Owen, who were leaders as pastors and theologians of their time, often engaged in culture against social pressures and were outspoken on the urgent message of the gospel. They were among numerous Puritans, common, notable, and well-known, who loved God’s word, the fellowship of believers, the sharing of their faith, the communion of the saints, devotion to prayer, and worship in church and among family. They were moved by the Spirit and inner motivation to live as spiritually anointed people consecrated from England’s and greater Europe’s society. They lived out the gospel’s implications to holy living and a commitment to love God and one another. The Puritans have a well-known reputation for an orderly life faithful to God by the authority of Scripture and the inner presence of the Holy Spirit.

Background

The history of the Puritans from the Reformer’s roots extending back to the Roman Catholic Church (RCC) involved the Church of England (COE) and its leadership. As this history was contentious, the specific issues and objections of the Puritans centered upon Catholicism as a whole system of belief. As Catholicism propagated the term “protestants” as a pejorative to non-Catholic Christians, the Puritans, in turn, wrote and spoke of Catholics as “papists.” The separation between the Catholics of tradition, which confer authority of the magisterium alongside the Scripture, and Christians, who place the supremacy of Scripture as the center of holy living, faith, and obedience, was squarely centered upon where authority rests. While the RCC and COE believed that ultimate spiritual authority is shared between Scripture, tradition, and the catechism of the magisterium, Puritans of the 17th century strenuously objected common to the doctrines and biblical beliefs of the Reformers.

Thomas Watson was a highly educated preacher and writer, having attended and graduated from Emmanuel College, among other Puritans of the time. John Owen, a highly popular author and speaker was thoroughly educated and influential before, during, and after serving as vice-chancellor of Oxford University. Watson and Owen were at the public’s service as ministers but never really were accepted in their own country as such, according to J.C. Ryle (1816 – 1900), a widely known Anglican Bishop of England. The Puritans, educated, influential, and fearless of men, greatly feared God in their life and work, as evidenced by their writing, preaching, and pastoral duties. English Puritan ministers numbered in the hundreds with far more congregant believers, including Scottish and Dutch populations served by men as non-conformists of the Church of England, the Church of Scotland, and the Roman Catholic Church.

The inner sense of Puritan devotion to God and His Word brought the ministers to a place of outspoken concern that urged people to know God, love Him, and serve Him from growing faith, devotion, and obedience. The Puritan interest in personal sanctification was intense, and their spiritual development involved lasting attention to holy living. The presence of sin in a believer’s life was intolerable. The presence of sin in an individual, the community, and the church was a frequent object of piercing attention, particularly among the leadership of Puritans, Watson, and Owen. Their views were spoken and written about at length concerning the specifics of sin and the urgent need for repentance. The immediate specifics about sin and repentance as a soteriological concern were pressing. Not purely as a general interest, as both Watson and Owen significantly contributed to Puritan theology and doctrine, but as a practical matter. To them, it just was not enough to write about the anthropological concerns about the sinful human condition. The prevailing concern was about what that meant to anyone who must repent for reconciliation to set a new course in pursuit of God and rebirth into a spiritual life of regeneration for the right standing of the growing converted.

17th Century Puritan Thought on Sin

To the Puritans, sin in the life of the regenerate and unregenerate alike was a major and lasting concern. The development of Puritan theology about the effects of sin arises from a biblical conviction that it is corruptive as it separates the soul from God, the Creator. The imputation of Adam’s guilt upon persons down through redemptive history is rooted in Puritan thought as it had explanatory power about its indwelling and inherently corrosive effects (Romans 5:12-21).1 Anthony Burgess (1600 – 1663), another Puritan of the 17th century, wrote in his Treatise of Original Sin about the necessity of Christ’s imputation of His righteousness in believers as developed within the Puritan doctrine of justification. His treatise examined the necessity of Christ’s imputation of His righteousness as Adam’s sin imputed his guilt upon humanity.2 Within Puritan thought, sin was imputed and inherent in persons, whether redeemed or not. Yet it was by mercy made necessary to redress that guilt through the “washing of regeneration” (Titus 3:5 NASB) by a covenant of grace that God implemented through the work of Christ Jesus. Puritan thought on the depth and profound meaning of the gospel continues to have a bearing upon soteriological doctrines in the church today as Scripture reveals Christ’s work inclusive of atonement “for the sins of many” (Hebrews 9:28).

The “atonement” concerning sin is often understood as “at” and “one” as it is derived from the English use of both terms and their meaning. The term “atonement” is an etymological marker that describes reconciliation between God and sinners made effective through the death of Jesus Christ on the cross.3 This definition of atonement has an explicit meaning that is thoroughly historical and biblical. From the earliest books of the Torah and throughout the canon of Scripture, readers can find acts of atonement as a redemptive matter to recover people from their sins. Whether through sacrificial offerings (Exodus 29:37, Leviticus 5:6), to the imagery of John’s revelatory vision (Revelation 5:9), readers recognize the atoning work of God through His incarnate presence to reclaim humanity from the separation of imputed and inherent sin. His work is a means of deliverance to return people to Himself for his glory and the salvation of a regenerated people He decides to bring to Himself. It is necessary to become regenerated from a corrupted nature and clothed with another to enjoy Christ eternally.4

Thomas Watson

Thomas Watson (1620-1686) was an English, Puritan preacher and author. He was among the thousands of Puritan ministers ejected from their parishes by the Church of England (COE). From the Restoration of Charles II, the monarch of the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland, the State used its power to remove Puritan ministers from the COE to enforce conformity to its doctrines and liturgical practices. The State sought to assert its place within the COE under the pretense of Christian unity among the Anglo kingdoms. As the COE separated from the Roman Catholic Church in Europe, it sought to impose its form of prescribed worship throughout the kingdoms according to State dictates. The Church of England and the government of England under Charles II betrayed faithful ministers of Christ by instituting the Clarendon Code. The Clarendon Code was a State-enforced public “cancellation” of individuals who did not conform to the COE but instead held to emergent and formative Reformed traditions centered upon the exclusive authority of biblical meaning toward faith and practice.

Free Church Persons (“non-conformist protestants”) were actively persecuted by penal laws that involved forfeiture, civil penalties, criminal sanctions, and cultural isolation that excluded ministers from public life and society. For example, university degrees and access to public services were some of the fallout of the political dismissal and removal of ministers faithful to the gospel and holy living according to the imperatives of Christ and supremacy and sufficiency of God’s Word. Various historical figures of notable reputations have assailed the actions of the COE, and over time “England succumbed to a culture of liberalism, overrun with cold, dead churches awash in apostasy and spiritual darkness.”5

Among the thousands of other Puritans scattered after the Great Ejection of August 24th, 1662, Thomas Watson continued to minister privately without ordination within the Anglican church. After Thomas Watson was removed by dismissal, according to the Church of England and the State’s use of force, the COE never recovered, just as J.C. Ryle speculated. Three years after the Great Ejection, the bubonic plague struck England and killed over 100,000 people. Shortly after, London was engulfed in a large fire that destroyed over 13,000 homes, nearly one hundred churches, and St Paul’s Cathedral. The Church of England has been fraught with controversy and apostasy for centuries and has fallen out of communion with other Anglican churches in various countries. The Church of England continues to self-assert its authority over Scripture as it grows into an ecclesial agency for public interests in service of the State. The Anglican church today is nothing close to what it once was with its historically influential members (C.S. Lewis, John Stott, J.C. Ryle, N.T. Wright, and others).

Thomas Watson continued ministry after being removed from his London parish after the Great Ejection but continued to preach privately. He was educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he was noted for remarkably intense study. In 1646 he commenced a 16-year pastorate at St. Stephen’s, Walbrook. While Watson held strong Presbyterian views during the civil war; however, in 1651, he was imprisoned briefly with some other ministers for his share in Christopher Love’s plot to recall Charles II of England. He was released on June 30th, 1652, and was formally reinstated as vicar of St. Stephen’s Walbrook. He obtained great fame and popularity as a preacher until the Great Ejection, when he was removed from the Church of England for nonconformity. Notwithstanding the rigor of the acts against dissenters, Watson continued to exercise his ministry privately as the opportunity presented itself. After preaching there for several years, his health declined, and he retired to Barnston, Essex, where he died suddenly while praying in private. He was buried on July 28th, 1686.

The Effects of Sin Upon Persons

Watson offers nine specific considerations concerning the effects of sin on persons. Beginning with the shame it causes, across the pages of his questions and discourse, his verbatim thoughts from the 1600s are outlined as follows:6

1. Every sin makes us guilty, and guilt usually breeds shame.

2. In every sin, there is much unthankfulness, and that is matter of shame.

3. Sin hath made us naked, and that may breed shame.

4. Our sins have put Christ to shame, and shall not we be ashamed?

5. Many sins which we commit, are by the special instigation of the Devil, and will not this cause shame?

6. Sin, like Cyrcies enchanting cup, turns men into beasts, and is not that matter of shame?

7. In every sin, there is folly (Jeremiah 4:22).

8. That which may make us blush, is, that the sins we commit are far worse than the sins of the Heathen (Indian): we act against more light

9. Our sins are worse than the sins of the Devils.

a. The angels never sinned against Christ’s blood

b. The devils never sinned against God’s patience

c. The devils never sinned against examples made for them by any fallen before

Watson further points out that sin is not an offense as a singular one-off as it often is, but a condition prevalent within as a whole. He clarifies that before a person can come to Christ, he must first come to himself, as persons are veiled by ignorance and self-love and cannot see the deformity of their souls. It darkens the intellect and reasoning. Moreover, justification of sin, indifference to it, and crafting a theology to suit one’s interests from socially loaded interpretations of Scripture forms iterative self-deluded thought about sin and its consequences.

To further understand the effects of sin within the Puritan mind, it is helpful to recognize it as a personified enemy (Genesis 4:7). To review the theological meaning or definition of sin without secular taint or influence requires a summary of historical doctrine rooted in Scripture. To thoroughly hate and loathe sin, it is necessary to attempt a meager view of what it is as a personified enemy. As sin in all its forms is an enemy to believers, it is enough to only see it as evil thoughts, feelings, words, actions, and omissions that violate the moral standard of God. Sin is the transgression of something forbidden, or it ignores something required by God’s law or character. Yet, Apostle Paul’s understanding of sin involves an analysis of anthropology and soteriology from his written letter to the church in Rome (Rom 7-8). While he writes of sin as an echo personified, actual human sinning always remains in full view of resistance against God. To this extent, its personification helps us recognize sin as the totality of human failure and depravity.7 Moreover, to quote Puritan Ralph Venning (1622-1674), “Sin is worse than Hell.… There is more evil in it, than good in all the Creation.”8 He elaborates further to explain that there is more evil in sin that hurts people than all of the good within Creation that does us good.

To Watson, the absence of shame among the impenitent places them farther from repentance. The unjust know no shame (Zephaniah 3:5), and many sin away the capacity to know or feel shame. Historically, the LORD branded His people, the Israelites, due to their shame. That they had no shame was their shame. They were branded that way (Jeremiah 6:15). Worse yet, Watson observes that those without shame grow to become proud of their sins and glory in them (Philippians 3:19). More plainly, those without shame can come to parade their offenses against God and become proud of them. To the believer, Watson urges the penitent to blush, as described by Ezra (Ezra 9:6). Believers who claim Yahweh as their God without shame stemming from personal sin live or think by the hypocrisy that affects their view of His grace.

To further recognize the severity of sin, Watson observed that the frequency of sin a person commits has a bearing upon the difficulty in which it is possible to repent. Watson compares the Angel with a flaming sword and a person’s conscience to contrast the severity of succumbing to temptation. Finally, to make his point scripturally grounded, he references Job 24:13, where there is the prospect of sinning against the light. As light is necessary for the growth of trees to produce fruit, it cannot, as sin darkens the soul against it. As Watson vividly illustrates, sin within an impenitent bears a fruitless, barren, and desolate heart and cannot intake the grace, mercy, and provision to recover. While Apostle Paul informs his readers, “where sin increased, grace abounded all the more” (Romans 5:20), Watson illustrates the blacksmith’s metal plunged into the fire, where it does not melt or become refined and has little hope. The tree cannot produce fruit as it is darkened and whithered by sin. It becomes cursed and does not bear fruit (Mark 11:15-21). Watson clearly distinguishes the condition of persons affected by sin as those who sin for want of the light compared to sinning against the light (Job 24:13). However, Watson does not offer a written rationale here about Christ Jesus’s urging for forgiveness up to seventy-seven times (ESV, NIV, NRSV, NRSVCE, NABRE) or seventy times seven (LSB, NASB, ERV, KJV, NKJV, HCSB, RSV, ASV, AV1873, RSV2CE, ESV-CE, CSB, NLT, LEB) in Matthew 18:21-22 to render forgiveness to the penitent.

Persons’ Proper View of Sin

From the Puritan perspective, it is necessary to understand that numerous evils explain what sin truly is. The scope and depth of offense concerning sin are immeasurable, but its effects help readers understand what it is by what it does. At least from a human perspective, sin has tangible effects as it has a bearing on people at various levels. However, as the view of sin is from a horizontal perspective, it is urgent to recognize it as a vertical matter between God and people, which is of grave importance. While sin estranges people from God (Isaiah 1:4, Jeremiah 2:5), it is a matter of walking contrary to God and His intentions. To Watson, with every step the soul goes further from God, the nearer it approaches misery and darkness.

Theologically, sin is described in Scripture as having wages. When Apostle Paul wrote to Romans that “the wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23), he chose the term “wage” to convey the idea of payment for sin. The semantic range of the Greek term for wages (opsōnia) is very limited, but it refers to the idea of payment or compensation for a rendered act of a worker or soldier.9 Where a person who sins renders payment for it, and its currency comes in the form of death. For both imputed guilt of sin through Adam and inherent sin in a person’s life, death is an inevitable consequence, and it serves as a payment for rendered wrong against God, oneself, and others. While the first sin we know about originates from Satan as attempting to elevate himself above God, the effects of sin on humanity extend back to Eden. As the spiritual death of Adam and Eve accompanied their decay and death, so does it to everyone without Christ.10

The theological topic of hamartiology is the study of sin. It is a biblical and systematic theology topic with numerous intertextual references rendered within Scripture throughout revelatory history. With numerous fields of thought among historical Puritan writings and theologians today, a contemporary and popular systematic theology defines sin as follows: “Sin is any failure to conform to the moral law of God in act, attitude, or nature. Sin is here defined in relation to God and his moral law. Sin includes not only individual acts, such as stealing, lying, and committing murder, but also attitudes that are contrary to the attitudes God requires of us.”11 Sin more explicitly understood as disobedience to the ten commandments (Exodus 20:1-17) extended more broadly from Christ Jesus’ sermon on the mount found within the gospel of Matthew, chapters 5 through 7 reveal to us that the intentions of the thoughts and heart also constitute sin. In the New Testament context and throughout Scripture, God incarnate reveals the spirit of the law and grace through all covenants. Particularly from the protoevangelion to the eschaton, Christ Jesus fulfills the law (Matthew 5:17-20) and renders His righteousness to sinners saved by grace through faith (Ephesians 2:8-9).

To the Puritan way of thinking about sin, it is a manner of being that must be “mortified.” The old English term “mortification” is a Puritan way of saying “put to death.” As old English translators interpreted Apostle Paul, “For if ye live after the flesh, ye shall die: but if ye through the Spirit do mortify the deeds of the body, ye shall live” (Romans 8:13 KJV). It is this reference that “putting to death” the deeds of the flesh are widened to mean “putting to death sin,” or as phrased by Puritan John Owen and John MacArthur Jr., “the mortification of sin”12 to convey the proper gravity of the total message.

John Owen

John Owen (1616 – 1683) also wrote about the “Mortification of Sin” to aid the reader’s views about sin and the severity of its effects and what it does. Before beginning with Owen’s views representing Puritan thought on sin, a brief introduction of him is in order. As John Owen was called the “prince of the English divines,” “a genius with learning second only to Calvin’s,” and “indisputably the leading proponent of high Calvinism in England in the late seventeenth century,”13 he demonstrated at an early age his trajectory to become an astute theologian, speaker, author, and pastor. Owen was an effective advocate for Reformed theology and Puritan piety. His life was remarkable as a shepherd, manager of university groups, statesman, chaplain, minister, and author of numerous works. His speaking drew numerous people to him as his messages were impressive and of considerable influence to people of political and religious power. He was also a chaplain to thousands of soldiers involved in harrowing conflicts who pleaded for Parliament’s mercy upon the Irish from English soldiers trained and ministered to around Puritan piety.

Owen’s family and career were difficult with trials and hardships compared to others during the Puritan era. Of 11 children born to him and his wife Mary Rooke, ten did not survive past their infancy. Their daughter, who did survive into adulthood, did not live a full life and died of tuberculosis (consumption) just after marriage. His career in ministry was fruitful but often was accompanied by uncertainty, instability, and disappointment. While interpersonal relationships from early in Owen’s career for years into midlife were characteristically productive and rewarding, he eventually became estranged from the fellowship of colleagues related to the Great Ejection imposed by the Church of England.

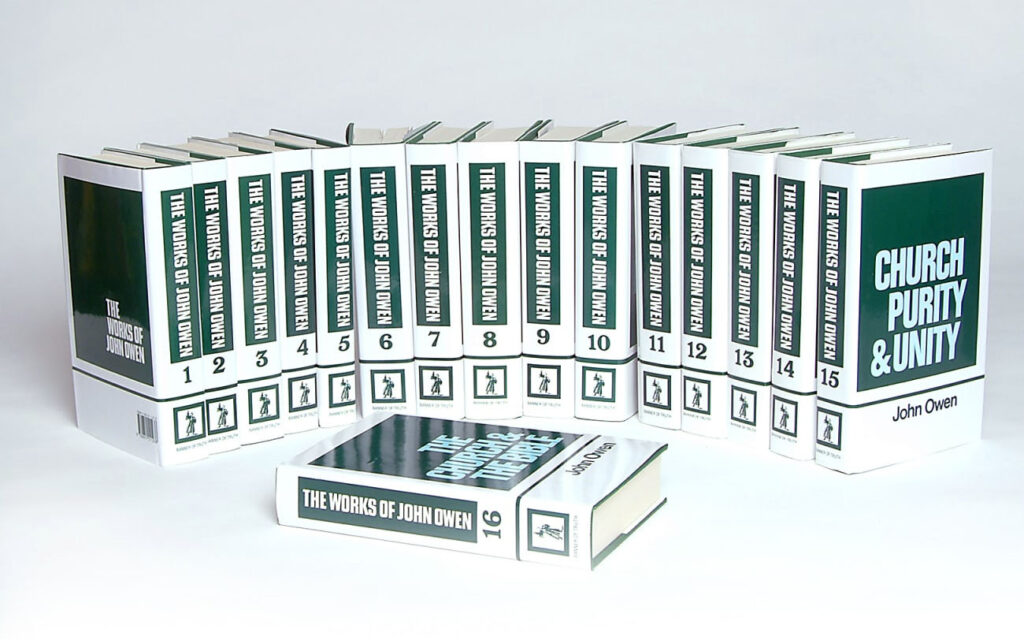

During his later years, he was without interpersonal influence, even while invited to serve in ministry elsewhere and support fellow ministers where he could. Instead, he wrote volumes that were published and remain in print today. His work ranges from more theological topics that further develop doctrines within the Church. He wrote a Biblical Theology, treatises, expositional commentaries, and practical guides to godly living. His many sermons were later transcribed and published for church development, instruction, and advancement.14 The following correspondence quoted verbatim gives the reader a sense of sentiment and scale.

TO MRS COOKE OF STOKE NEWINGTON

MADAM,—Four years ago the world was favoured, through your means, with a volume of Dr. Owen’s sermons which never before appeared in print; and it is at your instance that the following Sacramental Discourses of that same venerable divine are now made public. Hereby, madam, you at once express your high value and just esteem for the memory and works of that incomparable author, with your generous concern and prevailing desire of being serviceable to the cause of Christ;—a cause much more dear to you than all the worldly possessions with which the providence of God has blessed you.

With the greatest sincerity it may be said, your constant affection to the habitation of God’s house,—your steady adherence to the peculiar doctrines of Christianity,—your kind regards to the faithful ministers of the gospel,—your extensive benevolence to the indigent and the distressed,—your affability to all you converse with,—and, in a word, your readiness to every good work, are so spread abroad, that, as the apostle says to the Thessalonians, “There is no need to speak any thing.”

That the Lord would prolong your valuable life, daily refresh your soul with the dew of his grace, and enable you, when the hour of death approaches, to rejoice in the full prospect of eternal life through our Lord Jesus Christ, is the prayer.

Madam,

Of your affectionate and obedient servant,

RICHARD WINTER

TOOKE’S COURT, CURSITOR STREET

March 4, 1760.

From among the numerous volumes and sermons that originated from Owen, this segment of the post captures some of his thoughts on the subject of sin just as it concerned Watson and various other Puritans. Aside from Owen’s work entitled Indwelling Sin, an exposition of Psalm 130, he wrote The Mortification of Sin, as earlier indicated in this post, to correct the “dangerous mistakes” of various ministers who had fallen into error.15 While Owen’s treatise on the mortification of sin is embedded deep within this volume of work, it is also separated out as informative subject matter for modern readers to process personal understanding and application.

Sin as a Mortal Enemy

John Owen wrote his treatise on killing sin many years before its publication in 1862. Still, the subject matter was carried forward differently and directly for a more thorough understanding within the Puritan church in England. Owen’s effort included a comprehensive message concerning what Apostle Paul wrote to the churches in Rome and Colossae. Specifically, the 17th-century Puritan was highly concerned about the presence of sin in the lives of believers, and he wrote a widely read examination of what putting sin to death looks like. While the mortification of sin was John Owen’s pressing concern, he offered encouragement, exhortation, clarity, and guidance to understand what sin is and does. He had specific thoughts about what it is to eradicate its root by the Spirit and the involvement of the believer’s intentional will. In old English parlance familiar to Owen:

“For if ye live after the flesh, ye shall die: but if ye through the Spirit do mortify the deeds of the body, ye shall live.” – Romans 8:13 KJV

“Mortify therefore your members which are upon the earth; fornication, uncleanness, inordinate affection, evil concupiscence, and covetousness, which is idolatry: For which things’ sake the wrath of God cometh on the children of disobedience.” – Colossians 3:5-6 KJV

Sin is so grave that it eternally damns people, according to Scripture. Owen, just as Paul did, wrote of “mortifying” it. As mortification is an old English translation rendering, it corresponds to “putting to death” among modern translations (ESV, NIV, NKJV, HCSB, and more). The term “mortify” is translated the same in both references in Romans 8:13 and Colossians 3:5, while their Greek root terms are different.

Furthermore, to Owen, mortification, or to mortify, is understood from multiple perspectives, all consistent in meaning. The act of self-denial or the “putting to death” of sinful instincts or cravings is to render a person free from sin to live in the power of the Holy Spirit. The NT stresses that this act of humiliation comes about through the grace of God. It is the result of, not the condition for, conversion. The key passages Paul wrote correspond to numerous principles Owen stressed as they support the Reformed tradition together.

To further elaborate, mortification is “the process of ‘putting to death’ one’s sinful nature as the old self continually struggles because of the reality of indwelling sin. This process takes place in the lives of believers who, while they have been set free from sin’s dominion by the indwelling Holy Spirit who unites them to Christ, are called to live in light of God’s grace.”16 As persons actively work out their salvation, “if it is truly part of sanctification, it must be accomplished through the Spirit of Christ in dynamic interplay with a believer’s response of repentance; mere human effort does not result in increased freedom from sin, even if it changes outward behavior.”

To Owen’s discourse in his volume on mortification, while a person could successfully overcome sinful behaviors, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the instincts and cravings were put to death. Compared to Reformed theology, Catholicism also emphasizes Galatians 5:24, where it is necessary to “crucify the flesh.”17 As some English translations render “consider as dead” (NASB, LSB) in a passive sense, many other translations (including various Catholic translations) are active with the “put to death” language. For example, the “Little Rock Catholic Study Bible,” “New American Bible: Revised Edition” (NABRE), “The Revised Standard Version, Catholic Edition” (RSVCE), “Douay-Rheims Bible” as mortify (D-R), and the “Ignatius Bible: Revised Standard Version, Second Catholic Edition” (RSV2CE) all express the same meaning. When delving further into the definition of the terms nekroō (νεκρόω) in Colossians 3:5 and thanatoō (θανατόω) in Romans 8:13, they both correlate to the “put to death” sense of meaning. The Louw-Nida Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament ties both terms together as figurative in suggestive meaning where intended readers understood the original root manuscripts as conventional figures of speech to communicate the same idea.18

Owen is clear in his volume that mortification is not a passive posture of sin in the flesh as mere recognition or consideration from a believer. He stresses that it is an active conscious effort of someone as a converted person who became a believer by faith and repentance. However, he also recognizes that the process of mortification is lifelong, and it depends solely upon the Spirit of Christ to definitively accomplish the continued crucifixion of sin in the life of a believer. The believer is participative by necessity but is not the practical and final means of mortification. The Spirit of Christ is who does the work. As sin was put to death in the sacrifice and resurrection of Christ Jesus, the law of death is applied to sin itself in the lives of believers. Where there Spirit lives within believers, there is the law of life by the Spirit as long as there is no yield to sin. That sin is persistently, iteratively, and ruthlessly killed actively about particular offenses. Mortification is “the slaying of the disease of the soul, and by slaying this disease, it restores and invigorates the soul’s true life.”19 Still, mortifying the flesh is an intentional effort of faith, necessary to sanctify believers who work out their salvation with fear and trembling (Phil 2:12-13).

Sin in the Life of a Believer

As it is impossible to earn salvation through works or efforts that yield positive outcomes and the removal of sins, if efforts of mortification are not by faith, they are of no spiritual value. Owen asserts that such progress involves the replacement of sins with others in the absence of necessary faith through the heart of a believer concerning the treacherous and destructive nature of sin. Under the authority of God’s Word as written by the Holy Spirit through the Apostle Paul, those who live by the flesh will die. In contrast, those who live by the Spirit shall live. To be more explicit, regarding the term “flesh” (Rom 8:13 KJV), John Chrysostom (347 – 407 A.D., Archbishop of Constantinople) refers to it as follows: “what Paul means by the flesh in this passage is not the essence of the body but a life which is carnal and worldly, serving self-indulgence and extravagance to the full.”20

Owen’s readers might also remember Jesus’s parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). And specifically, verse 25: “But Abraham said, ‘Child, remember that you in your lifetime received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner bad things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in anguish (see Luke 6:24; Job 21:13; Ps. 17:14). The comparative man who fared “sumptuously” (Luke 16:19) was condemned. Where the rich man in the parable was delighted, glad, and enjoying himself in celebration and rejoicing by dining and merriment, there was apparent opulence that highlighted the disparity between him and Lazarus.

A surface reading of Owen’s treatise on sin to get a topical understanding of what he wrote doesn’t offer the best outcome for retention and application. More fully grasping what Owen wrote here concerning the killing of sin is challenging because it is a large and weighty subject. So this is a volume to iterate upon as John Owen is so widely read and studied for evident reasons. Nevertheless, his pressing concern about the lifelong urgency of killing sin within is not just a daily call to repentance but a persistent and ruthless inward campaign to find and destroy anything remotely innate or inherent that raises itself against God and the Spirit of Christ.

17th Century Puritan Thought on Repentance

Of particular interest during the Puritan era was the persecution of the Church of England while they were called to repentance by numerous people of the Reformed tradition. Numerous Puritan figures, such as Thomas Watson and John Owen, spoke and wrote of the urgency of persons to repentance. That effort extended to academic institutions, churches, parishes, and individuals in a desperate spiritual condition, estranged from God and proper worship for ongoing discipleship and sanctification befitting the Kingdom. The Puritan chorus of repentance was loud and clear, whether on a corporate scale or to individuals.

Thomas Watson

To include Watson’s work on repentance, he wrote correspondence to readers about its importance. He wrote that biblical repentance should not be spoken of as difficult and offered various influential people’s perspectives about what it does and why it is so necessary. He wrote that excellent things deserve labor, and it is better to enter Heaven with difficulty than to Hell easily. He inferred that repentance is difficult by comparison, but not to draw upon the reader’s attention or the impenitent to dissuade its necessity somehow. Watson used figurative illustrations often and one of digging for gold through ore to indicate that the effort of repentance is not worth discussion or concern by comparison because gold is the object of labor. The work of digging or smelting is not meant to dwell upon, contemplate, or resist. Repentance involves difficulty, but it is incredibly inappropriate and off-minded to think of it as such compared to what it yields. In so many words, Watson highlights that the absence of repentance in a person means a life of misery, scorn, and alienation from God.

Watson further stresses that accepting repentance as urgent and perpetual is of utmost necessity. Making peace with God on this side of the grave is putting sins to their death as a figurative act of drowning them in a deluge of water rather than having the soul burn in a symbolic unquenchable fire. Watson calls readers to consider what the Saints of old have done to imbitter themselves against sin, sacrifice their lusts, and put on sackcloth of the heart in the hope of the white robes of purity. Example after example, Watson’s reader is presented with historical figures who repented by bemoaning and humbling themselves to prevent and correct unacceptable thoughts and behaviors hideous before God.

Watson’s treatise on repentance is supported by a helpful understanding as it is biblically and confessionally defined. As Scripture carries the greatest and final weight of authority in terms of intended meaning rendered by the Holy Spirit through the biblical writers, the Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF) larger catechism offers the following (WLC Q76):

What is repentance unto life?

Repentance unto life is a saving grace, (2 Tim. 2:25) wrought in the heart of a sinner by the Spirit (Zech. 12:10) and word of God, (Acts 11:18,20–21) whereby, out of the sight and sense, not only of the danger, (Ezek. 18:28,30,32, Luke 15:17–18, Hos. 2:6–7) but also of the filthiness and odiousness of his sins, (Ezek. 36:31, Isa. 30:22) and upon the apprehension of God’s mercy in Christ to such as are penitent, (Joel 2:12–13) he so grieves for (Jer. 31:18–19) and hates his sins, (2 Cor. 7:11) as that he turns from them all to God, (Acts 26:18, Ezek. 14:6, 1 Kings 8:47–48) purposing and endeavouring constantly to walk with him in all the ways of new obedience. (Ps. 119:6,59,128, Luke 1:6, 2 Kings 23:25)21

The WCF is a confessional document that helps define individuals’ beliefs aligned with the biblical meaning of topics rooted in the Scriptures’ authoritative supremacy. Biblically, repentance is a critical element of conversion. To define and understand “conversion,” it must include faith and repentance, as commonly understood by the Greek term metanoia (μετανοέω).22

As the gospel reader first sees the term in the opening proclamation of Jesus’ ministry (Matt 4:17), it is defined through various cultural and Old Testament correlated references. Moreover, the term conveys the idea that it is about changing one’s mind with a feeling of remorse (Matt 3:2, 4:17, 11:21, Mark 1:15, 6:12, Luke 10:13, Acts 17:30, 26:20). While it is essential to recognize that repentance involves a change of mind, it also includes a changing of the will. It is the turning away from something as the conscious effort of a whole person away from personal self-destructive thoughts and behaviors offensive to God and people.

Unacceptable thoughts, words, and actions, biblically referred to as “sin,” are rejected as a whole toward a life commitment of faith to God through Christ. This is conversion. As one internally moves from one state of rejection (or indifference) involving a life of sin and selfishness to a faith commitment and devotion, Christ becomes Lord and King to a believer who chooses to surrender through grace. Conversion is by faith and a rejection of sin in part and as a whole, both retroactively and in the future, as defined through the pages of Scripture according to the intent of the biblical authors and not by reader-response interpretation.

Watson sets up a proposition within his treatise on repentance. He further makes biblically certain in his text, The Doctrine of Repentance, “Christ has purchased by His blood repenting sinners who shall be saved.” He reinforces that those who are made alive in Christ by a seed of faith have the spiritual capacity to repent, and as they do, they put to death sin as a prevailing matter of eternal consequence. Those who sin in the absence of the gospel of grace for repentance shall spiritually die without recourse (Galatians 3:10). Among the first and last words Jesus spoke from the pages of Scripture was “repent” (Matt 3:2, Luke 24:47). In fact, this was the urgency of the Apostles as they were sent out and preached, “people should repent” (Mark 6:12 ESV). They proclaimed that all should undergo a change of heart and mind. To abandon their former disposition with a new self, course of behavior, and regret over former life choices and dispositions. The abundance of their message concerning repentance was recorded in numerous locations throughout the New Testament (μετανοέω metanoeō repent (36x); Matt 3:2; 4:17; 11:20–21; 12:41; Mark 1:15; 6:12; Luke 10:13; 11:32; 13:3, 5; 15:7, 10; 16:30; 17:3–4; Acts 2:38; 3:19; 8:22; 17:30; 26:20; 2 Cor 12:21, Rev 2:5, 16, 21–22; 3:3, 19; 9:20–21; 16:9, 11).

Watson did not wish to argue whether or not faith or repentance comes first, while he was inclined to think that faith does precede repentance. He only sets the proposition that all people should repent, as conveyed by Christ Jesus and the urgency of the Apostles. The blood of Christ and the gospel of grace makes salvation to eternal life possible as people would repent. As persons repent and live by faith, they are saved by God’s doing, not their own. From grace and faith, people are saved through no other means (Ephesians 2:8-9). However, it is clear that without repentance, people will spiritually perish. Watson makes this point clear, as does Scripture. Watson wrote, “sin and die,” where the covenant of works (Mosaic law) offered no admittance through repentance. The law required personal, perfect, and perpetual obedience, where all eventually came under a curse. Under the new covenant of grace, Christians are solemnly urged to repent and be converted so that their sins may be blotted out (Acts 3:19).

Confession and Authentic Repentance

From Watson’s perspective, it is necessary to understand counterfeit repentance compared to authentic repentance, and to this end, he zeroes in on what false repentance is. He provides three critical specifics and examples that inform readers about what is necessary to recognize and understand what repentance is not. As a warning about what not to conclude concerning changes in behavior, attitudes, and motives, the absence of repentance remains in a person from three sources of false thinking about the matter. An unrepentant heart within a person represents no inward heart change about sin. As a person may delude himself with counterfeit repentance, these are the three warnings Watson wrote about:

Counterfeit Repentance: “Legal Terror”

Pain and trouble are not sufficient for repentance. Repentance requires a change of heart. If there is no change of heart, there is no repentance. An internal awareness of guilt that a person cognitively recognizes does not in itself mean that a change of heart has occurred. Watson contrasts self-aware guilt to an “infusion of grace” that infers the authenticity of repentance from Divine initiative and human reception. The differences between Reformed and Catholic doctrines of justification involve a change in the status of believers about how they are justified. While Reformed doctrine on justification holds to the principle of imputation of Christ’s righteousness to people of faith, Catholic doctrine decreed that justification involves an infused grace that changes a person’s internal nature and inclinations for sanctification and the remission of sins all at once (Council of Trent Decree concerning Justification, session 6, chapter 7).23 Whereas to Protestants, Christ’s righteousness is imputed into a believer once as a final justification (simul justus et peccator), to Catholics, infused righteousness is changed righteousness within the life of a believer as a result of faith and baptism.24 Here, Watson’s use of the phrase “infused grace” indicates a constituent gift of God that includes the ability of a believer to repent according to Divine intent and action (Ezek 36:27). More specifically, Watson wrote that infused grace breeds repentance.25

Counterfeit Repentance: “Resolution Against Sin”

To reject sin as a matter of self-determination and effort isn’t repentance. It is self-will that doesn’t accompany heart change from behaviors, thoughts, actions, or omissions offensive to God and contrary to what He expects. Counterfeit repentance in this form is a commitment to stop sinning, but for the wrong reasons. Resolutions against sin under these circumstances don’t hold, and some sins are replaced by others where the state of a person is the same or worse than before.

- Resolutions against sin aren’t because sin is sinful but because it is painful. There remains no change of heart, conviction, remorse, or awareness of offended God, whom a person sins against.

- Motivation to stop sinning from a position of alarm over judgment, evil, death, and Hell doesn’t win over a person’s love of sin. Love of sin will prevail over the dread of its consequences.

The sin of one type or another continues to surface because the old heart has not changed. New temptations continually overcome the old heart.

Counterfeit Repentance: “Leaving Sinful Ways”

A person who leaves numerous sins behind with a more righteous lifestyle doesn’t mean a person is repentant. Without a heart change, the person still in sin remains unrepentant. Watson wrote of leaving sin “from the strength of grace” compared to leaving on moral grounds. Selectively, some sins are retained while others are dropped and exchanged for others. The inclinations of the heart and its affections have not changed when a person remains captive to the appeal and love of sin. As Watson wrote that infused grace causes a cessation of sinful acts, grace is a gift and enablement of consistent holy living.

As it is necessary to understand what repentance is not, it is also essential to recognize what it is from Watson’s treatise. In comparison, Watson wrote more extensively on authentic repentance and the necessity of it than in all other chapters. He organized his thoughts into several categories where they must all be present for repentance to retain its virtue. He composed these categories as ingredients with Scripture references accompanying Watson’s points. Assertions and rationale about sin and the necessity of repentance resonate from his time to us who encounter his exhortations, rebukes, and encouragements. Beginning with these ingredients of repentance, we must fully grasp its meaning while checking our heart’s condition and motivations. All taken together, sin is the issue, and it bears acceptance that it is also a mortal enemy.

Watson wrote of the ingredients of authentic repentance as a mix of elements in contrast to counterfeit repentance. They are sequential or linear understandings to include the proper and correct view of sin, sorrow for it, the consequential experience of shame, personal hatred of sin, and finally, to turn from sin as a new life direction. Watson’s writings were formed from written lectures on the topic of repentance, including these categorical elements, and his materials were often presented pastorally. However, between all these points, Watson wrote at length about his views and verbal illustrations with Scriptural references to support his continued pressing argument. The inference was that readers were expected to retain the thread of rationale to hold together all ingredients without reinforcement and continued underlying support.

It is necessary to confess known sins before Lord when a believer becomes aware of them. This, too, is necessary for repentance. In confession, Watson makes the point that confession is self-accusation before God, where the adversary has no strength of argument against believers as they have already taxed themselves of pride, passion, and infidelity. Confession is a way to prove that we have judged and sentenced ourselves (1 Corinthians 11:31). Accusation of ourselves is, as Watson puts it, —me me adsum qui feci in me convertite ferrum26— (Me, I am here that I have done, turn the iron upon me). As Paul wrote to the church at Corinth, we will not be judged if we judge ourselves. By Cyprian, judicio, quod poenitentiae humanae severitas protulit, aliquid justitia coelestis apponit (to the judgment which the severity of human penitence brought forth, adds something of heavenly justice). Yet as we read various confessions within the biblical record, Watson makes a series of observations about what true confession is:

- Confession is voluntary as it acknowledges sin against God and Heaven.

- Confession is with deep resentment, burden, and compunction against sin.

- Confession must be sincere.

- Confession is without particularity.

- Confession is from an acknowledgment that the penitent is polluted by sin.

- Confession of sin is with all its circumstances and aggravations

- Confession is a charge upon ourselves so as to clear God that He has done no wrong.

- Confession is with a resolution never to act on them again.

To further understand the purpose of confession, Watson elaborates upon two areas of thought that demonstrate why rightful confession is necessary for repentance. In contrast, on the one hand, there is appeal and protest in prayer with partial confession, yet on the other, sincerity. So, as confession is a necessary ingredient in repentance, Watson wrote that four types of people do not fully accept the range and depth of it. And while Watson makes a compelling point about each, it does appear that they are not necessarily mutually exclusive from one another. Watson further frames his treatise around the idea of indictments. There are four of them against persons as if they were in a court of law to prosecute the abstention of full confessions that inhibit or block effective personal repentance.

- Hidden Sins – While it is possible to conceal sins from people, keeping them hidden from God is impossible.

- Partial Confessions – There is no expectation to confess a catalog of unknown sins but those we know about. All of them best we can where all sins shall be confessed, and nothing held back.

- Minced Words – Equivocations, Extenuating Circumstances, and Excuses (Genesis 3:12, 1 Samuel 15:24).

- Arguments – Self-justification and special pleading efforts at vindication (John 4:9).

In contrast to “repentance” of self-determination, penitents are sincere in confessing the specifics of their sin to demonstrate the heart and mind of repentance fully. The uses of confession in these ways are magnificent as they are by design and redemptive intent. They are pleasing to God and cause angels to rejoice. To outline Watson’s views of favorable repentance, they are as follows:

- Confession gives glory to God.

- Confession is a means to humble the soul.

- Confession gives vent to a troubled heart.

- Confession purges out sin.

- Confession of sin endears Christ to the soul.

- Confession of sin makes way for pardon.

- Confession is reasonable and easy.

It is rational to reconcile with your Creator, who enables you to live peaceably with people who are hostile to you and who themselves consider you their enemy. While evil people of darkness live in enmity with people of faith, grace, and repentance, it is unreasonable for forgiven believers to reciprocate by hatred. As God forgives believers who confess their sins, He expects us to forgive others. Christ requires that we forgive others (Matt 6:14-15) and love those who live in enmity with people (Matt 5:43-45) who live by the authority of His Word.

The first covenant (Mosaic law) compared to the second covenant (covenant of grace) is night and day different. The first covenant required death and sacrifice. While in the second, Christ is the atoning mediator who redeems believers and makes possible the covenant of grace for the redemption of humanity (i.e., those who would call upon him and convert by faith and repentance). By humble confession, Christ is our surety. Watson wrote, only acknowledge your iniquity, indict yourself, and you will be sure of mercy.

To whom we confess sin is of concern, as Watson wrote about the papists and hearers of confessions from believers who turn to people rather than God, who promises them forgiveness and cleansing (1 John 1:9). While we are instructed to “confess sins one to another” (James 5:16), Catholic priests do not confess to the people as the people confess to the priests. Like the common man, Priests certainly confess their sins to one another, but confession is not reciprocal as a body of believers from one class structure to another. Priests do not confess specific sins to believers of a congregation or mass, as do believers who appear before priests at confession for absolution. The Catholic church and priests aligned with the State are ready to hear confessions of sins against God and others but also sins against social order and the contradictory interests of the State, which insists upon its citizens’ loyalty above God (Eph 6:12). Confession in this way is a form of State surveillance.

Watson made the point that confession to priests is a profitable endeavor. Opening the mouth of a parishioner through guilt and the admission of guilt renders a return on effort in the form of restitution for absolution. For a price, donation as penance is Watson’s point about the folly of confession to some Catholic priests disinterested in restoring one believer to God, people, and the church. Watson does not support confessions to priests as given by papist doctrine.

The Necessity and Conditions of Repentance

The call to repentance is not a request toward people inclined to hear a passing suggestion. Both Watson and Owen spoke of repentance as imperative, necessary, urgent, and salvific. Moreover, Watson offers specifics about why repentance is a necessity.

- God, with ultimate authority, instructs and directs all people to repent (Acts 17:30). This is a command. Yet, it is reminiscent of the famous quote from Augustine, “Thou commandest continency (self-control); give what Thou commandest, and command what Thou wilt.”27 The work of repentance is a sovereign work of God through the free will of people. Paradoxically, to the command to repent, it is a gift granted (2 Tim 2:25).

- God will not accept anyone unless there is repentance (Ex 23:7, Isa 1:16, 2 Cor 6:14).

- People who continue in impenitence are not within Christ’s commission (see his commission, Isa. 61:1). He has been sent to the brokenhearted. As Watson puts it, “if ever Christ brings men to Heaven, it shall be through Hell’s gates” (Acts 5:31). It is Watson’s view that Christ will not save someone regardless of a person’s repentant heart.28

- We have, by sin, wronged God. By repentance, we humble and judge ourselves for the sin committed. We set to our seal that God is righteous if He should destroy us: thus, we give glory to God and do what is in us to restore his honor.

Watson further continues, “if God should save men without repentance, making no discrimination, then by this rule he must save all; not only men, but Devils, as Origen once held; and so consequently the decrees of Election and Reprobation must fall to the ground; which how diametrically opposite it is to sacred writ, let all judge.

At this point, it is necessary to make side observations about the role of Scripture in terms of its necessity toward repentance. It was Origen’s understanding that the Scriptural text is “sacramental,” according to Torjesen in her work, Hermeneutical procedure and theological structure in Origen’s exegesis (Patristische Texte und Studien). 29 She references de Lubac in her work about the literal and spiritual nature of interpretation. Henri de Lubac was a progressive Catholic priest early in life. Still, he later became accepted and admired after the second Vatican council and a lengthy period of alienation and censorship from the Catholic church.

While it is of interest to understand what de Lubac’s views were of Origen and the necessity of mysticism, there is significant thought and interest about the spiritually transformative nature of Scripture. The work and presence of the Holy Spirit are written as mystical to converted readers the text, and Gohl makes the following written assertion:

“For Origen, when Christians come into contact with the text, they are coming into contact with the Logos (Christ Jesus) Himself. Through this contact, the Logos instructs and transforms the Christian soul into His own likeness (2 Corinthians 3:18).”30 As this reference corresponds to Colossians 3:16 (“Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly…”), Origen’s views are better supported by James 1:21, which informs readers, “humbly accept the word God has planted in your hearts, for it has the power to save your souls.”

John Owen

The introduction of John Owen given earlier in this post offers some limited insight into his thoughts concerning sin. Yet further throughout his volumes are topics of justification and sanctification that involve the doctrines of repentance. Regeneration, saving faith, and conversion translate to the work of the Spirit, as repentance is given as a gift to believers who place their faith in Christ Jesus and draw near to Him in surrender. Owen makes clear the work of the Spirit within the believer to render the work of repentance and sanctification.

The Laboring of Repentance

Owen’s views about labor for repentance largely appear within his writings concerning apostasy. More specifically, concerning a departure from the holiness of the gospel, as warned about at length, to render an understanding of its consequences. To Owen, repentance was about abandoning sin for the right reasons and adopting holy living by forsaking known habitual sins. To overcome sin by continually striving against it until gone was to repent of it in Owen’s mind. The virtues of faith, love and various others intermingled with repentance as it is integral to remaining in a state of open-hearted confession and transparency before God as indwelling sin is perpetually put to death. While the Spirit is at work in the believer to mortify sin, the believer is mentally, physically, and spiritually exerting effort against the personal sin nature. Not merely by its actions or outcomes but to the source or root of it to cut off affections and inclinations from a changed heart that yields to the interests of God. The spirit is made alive with thoughts and intentions acted upon to recognize sin, and patterns of sin, that get attention to thwart it and cut it off. To Owen, this is an outworking of personal exertion and an inworking of the Spirit to judge and burn away what remains persistent (Isaiah 4:4). The cause and effect of mortification of sin and repentance are by the Spirit of God upon the spirit of a person. The Spirit, as the cause, presents affected outcomes to persons yielded to God through faith by grace.

Owen raises the question about how we are exhorted to repentance if it is to be the work of the Spirit alone. The question of obedience compared to the work of the Spirit appears as a paradox. On the one hand, He “works in us to will and to do of his own good pleasure” (Phil 2:13), while on the other hand, the Spirit works “all our works in us” (Isa. 26:12).

The Place of Granted Repentance

Owen is thoroughly clear and understood concerning his views about the work of Christ as a gift to believers who live by faith. He further reinforces this rationale from the John 15:5 passage: “Without Christ we can do nothing.” From the gift of repentance given to persons, the actual work of the Spirit is within and upon believers. Where the Spirit acts upon and within a person is the work of the Spirit alone. Incredibly, while Watson and Owen highlight the call to repentance, just as Christ Jesus did (Matthew 4:17), it is clear from Luke, “This One God exalted to His right hand as a Leader and a Savior, to grant repentance to Israel, and forgiveness of sins” (Acts 5:31 LSB). This giving of repentance extends from Christ as the Father has exalted Him. The Spirit that proceeds from the Father and Christ is the source of power to produce repentance and the killing of indwelling sin to assure personal sanctification.

The work of the Spirit as the helper is the gift of God from Christ the Son as God the Father has exalted Him to elevated stature and glory. In keeping with the rationale of repentance given as a gift, it is granted as an action that leads to knowledge of the truth (2 Timothy 2:25). When this question is asked of Owen concerning sanctification, “What is repentance?” He answers, “Godly sorrow for every known sin committed against God, with a firm purpose of heart to cleave unto him for the future, in the killing of sin, the quickening of all graces, to walk before him in newness of life.” He again follows up with a new question: “Can we do this ourselves?” With a definitive answer, “No; it is a special gift and grace of God, which he bestoweth on whom he pleaseth.” As it is written, it is God’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom (Luke 12:32), so it is with the gift of repentance to His pleasure, interests, and glory.

Conclusion

This research project was an exhilarating, sobering, and joyful experience. The Puritans of the 17th century offer a deep and rich perspective on godly living from the Reformed tradition we can all aspire to reach. There is much to learn from Puritan theology and their way of life. John Owen and Thomas Watson were gifted among numerous ministers of the Puritan era. They lived through an appointed time in history that God used to bring the message of sin and repentance to their generation and numerous others that extend across generations. The message to the people and the church of England concerning sin and repentance is just as relevant today as it was back during their time. Owen and Watson’s views are centered squarely on Scripture and not on tradition or a certain class of theology to which they are obligated to abide. The refreshing perspectives of careful and biblical thought from the Puritans of the 17th century offer a model of ministry, exposition, and work ethic that resonates strongly within the church today.

Citations

________________________________

1 Joel R. Beeke and Mark Jones, A Puritan Theology: Doctrine for Life (Grand Rapids, MI: Reformation Heritage Books, 2012), 205

2 Anthony Burgess, A Treatise of Original Sin … Proving That It Is, by Pregnant Texts of Scripture Vindicated from False Glosses / by Anthony Burgess, Early English Books Online (London: s.n, 1658), 46.

3 Donald K. McKim, The Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms, Second Edition, Revised and Expanded. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014), 22.

4 Stephen Charnock, The Complete Works of Stephen Charnock, vol. 3 (Edinburgh; London; Dublin: James Nichol; James Nisbet and Co.; W. Robertson; G. Herbert, 1864–1866), 15.

5 John MacArthur, “The Danger of Calling the Church to Repent,” April 11th, 2022, https://www.gty.org/library/blog/B181008/the-danger-of-calling-the-church-to-repent. Accessed 12/02/2022.

6 Thomas Watson, The Doctrine of Repentance, Useful for These Times by Tho. Watson, Early English Books Online (London: R.W. for Thomas Parkhurst .., 1668), 42.

7 M. de Jonge, “Sin,” ed. Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. van der Horst, Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (Leiden; Boston; Köln; Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge: Brill; Eerdmans, 1999), 782.

8 Ralph Venning, “Sin, the Plague of Plagues, or, Sinful sin, the Worst of Evil,” 1669, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo2/A64834.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext. Cambridge University Library. Accessed 02/19/2023.

9 William Arndt et al., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 747.

10 John MacArthur and Richard Mayhue, eds., Biblical Doctrine: A Systematic Summary of Bible Truth (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2017), 475.

11 Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine, Second Edition. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Academic, 2020), 619.

12 John F. MacArthur Jr., “Mortification of Sin,” Master’s Seminary Journal 5, no. 1 (1994): 4.

13 Joel R. Beeke and Randall J. Pederson, Meet the Puritans: With a Guide to Modern Reprints (Grand Rapids, MI: Reformation Heritage Books, 2006), 455.

14 John Owen, The Works of John Owen, ed. William H. Goold, vol. 9 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, n.d.), 519.

15 John Owen, The Works of John Owen, ed. William H. Goold, vol. 6 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, n.d.), 2.

16 Kelly M. Kapic and Wesley Vander Lugt, Pocket Dictionary of the Reformed Tradition, The IVP Pocket Reference Series (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2013), 76.

17 Charles G. Herbermann, Edward A. Pace, et al., eds., “Mortification,” The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church (New York: The Encyclopedia Press; The Universal Knowledge Foundation, 1907–1913).

18 Johannes P. Louw and Eugene Albert Nida, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains (New York: United Bible Societies, 1996), 660.

19 Ibid. Herbermann.

20 John Chrysostom, “Homilies of St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, on the Epistle of St. Paul to the Romans,” in Saint Chrysostom: Homilies on the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistle to the Romans, ed. Philip Schaff, trans. J. B. Morris, W. H. Simcox, and George B. Stevens, vol. 11, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1889), 434–435.

21 The Westminster Larger Catechism: With Scripture Proofs. (Oak Harbor, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1996).

22 Ibid. William Arndt et al. 640.

23 Theodore Alois Buckley, The Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent (London: George Routledge and Co., 1851), 33-34.

24 Michael Glazier and Monika K. Hellwig, The Modern Catholic Encyclopedia (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2004), 453

25 Ibid. Watson, 9.

26 P. Vergilius (Virgil) Maro, “Bucolics, Aeneid, and Georgics Of Vergil,” ed. J. B. Greenough (Medford, MA: Ginn & Co., 1900).

27 Augustine of Hippo, “The Confessions of St. Augustin,” in The Confessions and Letters of St. Augustin with a Sketch of His Life and Work, ed. Philip Schaff, trans. J. G. Pilkington, vol. 1, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1886), 155.

28 Ibid. Watson, 76.

29 Justin M. Gohl, “Origen,” ed. John D. Barry et al., The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

30 Ibid.

31 John Owen, The Works of John Owen, ed. William H. Goold, vol. 6 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, n.d.), 20.

32 John Owen, The Works of John Owen, ed. William H. Goold, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, n.d.), 487–488.

Bibliography

- Alois Buckley, Theodore. The Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent. London: George Routledge, 1851.

- Arndt, William et al. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Beale, G.K., and D.A. Carson. Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007.

- Beeke, Joel R, and Mark Jones. A Puritan Theology: Doctrine for Life. Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2012.

- Burgess, Anthony. A Treatise of Original Sin … Proving That It Is, by Pregnant Texts of Scripture Vindicated from False Glosses. London: Early English Books Online, 1658.

- Charnock, Stephen. The Complete Works of Stephen Charnock, Vol. 3. Edinburgh; London; Dublin: James Nichol; James Nisbet and Co., 1864–1866.

- Chrysostom, John. “Homilies of St John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, on the Epistle of St. Paul to the Romans.” In A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, by Philip Schaff, J.B. Morris, W.H. Simcox, & George B Stevens, 434-435. New York: Christian Literature Company, 1889.

- de Jonge, M. “Sin.” In Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, by Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, & Peter W van der Horst, 782. Leiden, Boston, Koln, Grand Rapids, Cambridge: Brill, 1999.

Glazier, Michael, and Monika K Hellwig. The Modern Catholic Encyclopedia. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2004. - Herbermann, Charles G, and Edward A Pace. “Mortification.” In The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. New York: The Encyclopedia Press, 1907-1913.

- Hippo, Augustine of. “The Confessions of St. Augustin.” In The Confessions and Letters of St. Augustin with a Sketch of His Life and Work, Vol. 1, by Philip Schaff, & J.G. Pilkington, 155. Buffalo: Christian Literature Company, 1886.

- Kapic, Kelly M., and Wesley Vander Lugt. Pocket Dictionary of the Reformed Tradition. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2013.

- Logos Research Systems, Inc. The Westminister Larger Catechism: With Scripture Proofs. Oak Harbor, 1996.

- Louw, Johannes P, and Albert Eugene Nida. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains. New York: United Bible Societies, 1996.

- MacArthur, John F. Jr. “Mortification of Sin.” The Master’s Seminary Journal 5, No.1, Spring 1994: 2-22.

- Maro, P. Vergilius. Bucolics, Aeneid, and Georgics of Vergil. Medford: Ginn & Co. 1900, 1900.

- McKim, Donald K. The Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms, Second Edition, Revised and Expanded. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014.

- Owen, John. The Works of John Owen, Vol. 1. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, N.D.

- —. The Works of John Owen, Vol. 6. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, N.D.

- —. The Works of John Owen, Vol. 9. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, N.D.

- R, Beeke Joel, and Randall J Pederson. Meet the Puritans: With a Guide to Modern Reprints. Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2006.

- EEBO – Early English Books Online. 1669. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo2/A64834.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext (accessed 02 19, 2023).