Dante Alighieri’s “Purgatorio,” the second cantica of his monumental epic poem “The Divine Comedy,” continues the journey of the poem’s protagonist—Dante himself—through the afterlife. Having traversed the depths of Hell in “Inferno,” Dante and his guide, the Roman poet Virgil, ascend to Purgatory, a realm where repentant souls undergo purification to prepare for their entrance into Paradise. Written in the early 14th century, “Purgatorio” is a rich tapestry of medieval theology, philosophy, political commentary, and poetic innovation.

Introduction

“Purgatorio” is structured around the concept of penance and redemption. The mountain of Purgatory, situated on an island in the southern hemisphere, opposite Jerusalem, is described as the only piece of land in that part of the world, formed when the earth recoiled from the sinful impact of Lucifer’s fall and rose up to create a place of purification. This mountain is divided into terraces, each dedicated to the purgation of one of the seven capital sins, in accordance with medieval Catholic doctrine.

Dante’s portrayal of Purgatory is ingrained with hope and the possibility of redemption, a stark contrast to the despairing and immutable punishments of Hell. The souls in Purgatory, though suffering, are characterized by their willingness to undergo penance and their joy in anticipation of eventual salvation. This fundamentally optimistic view reflects the poem’s underlying theological premise that God’s justice is tempered with mercy, and that repentance can lead to forgiveness and divine grace.

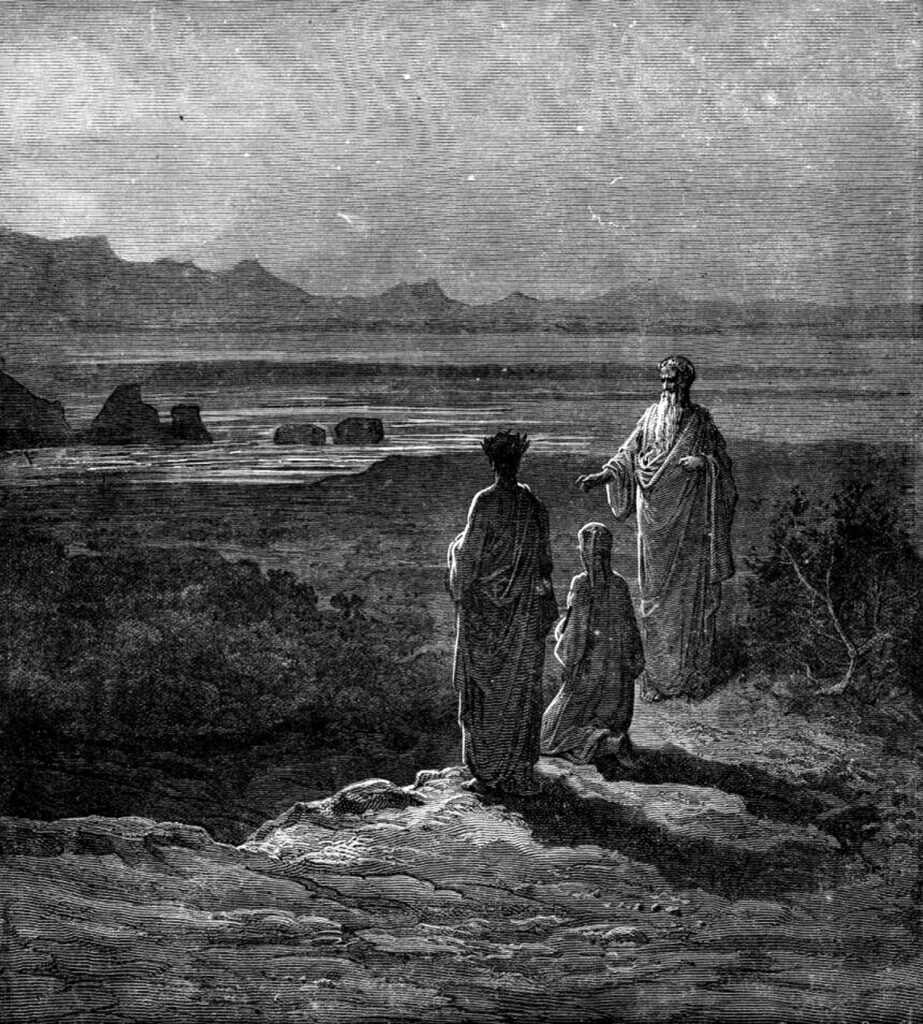

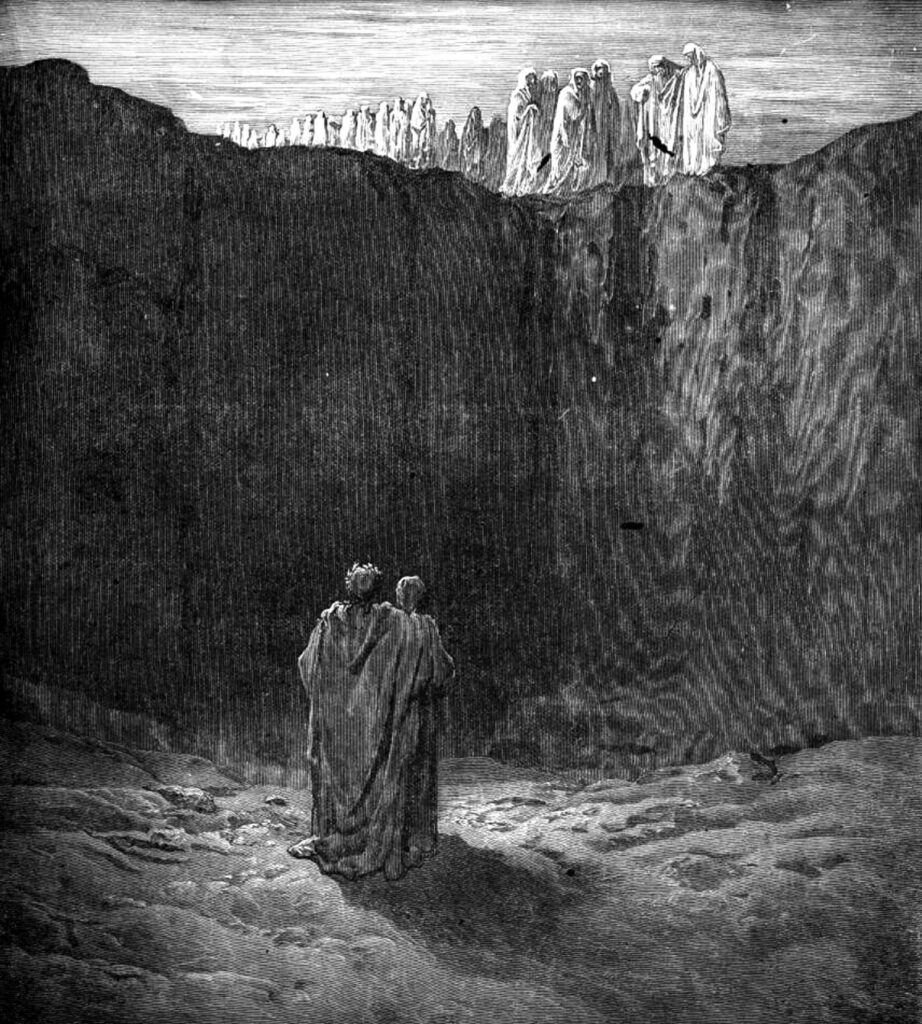

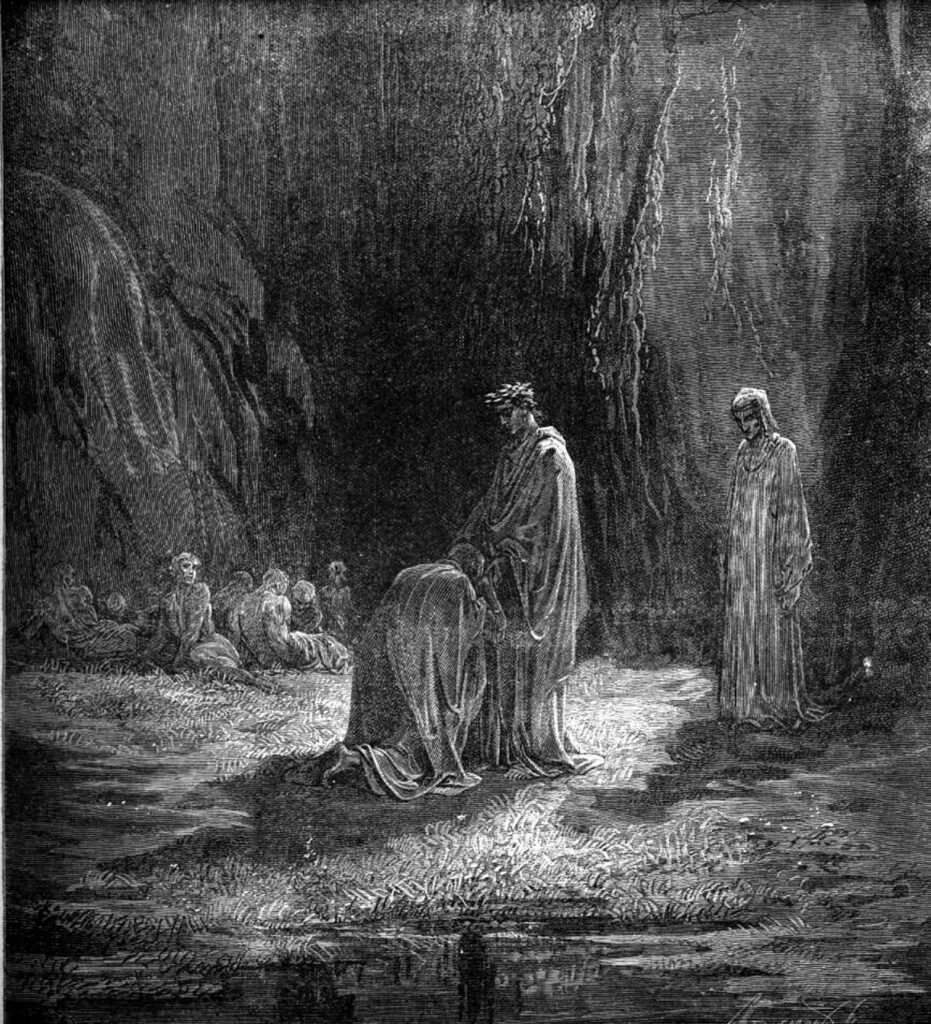

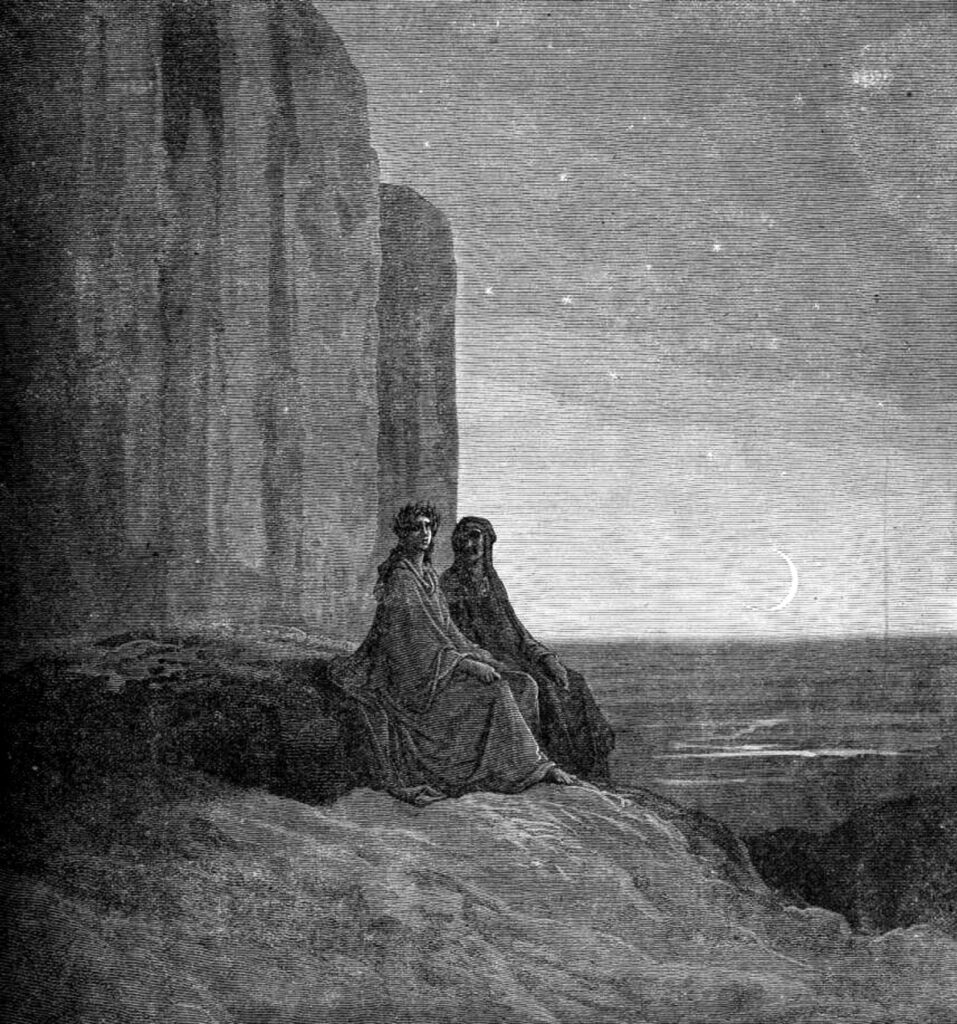

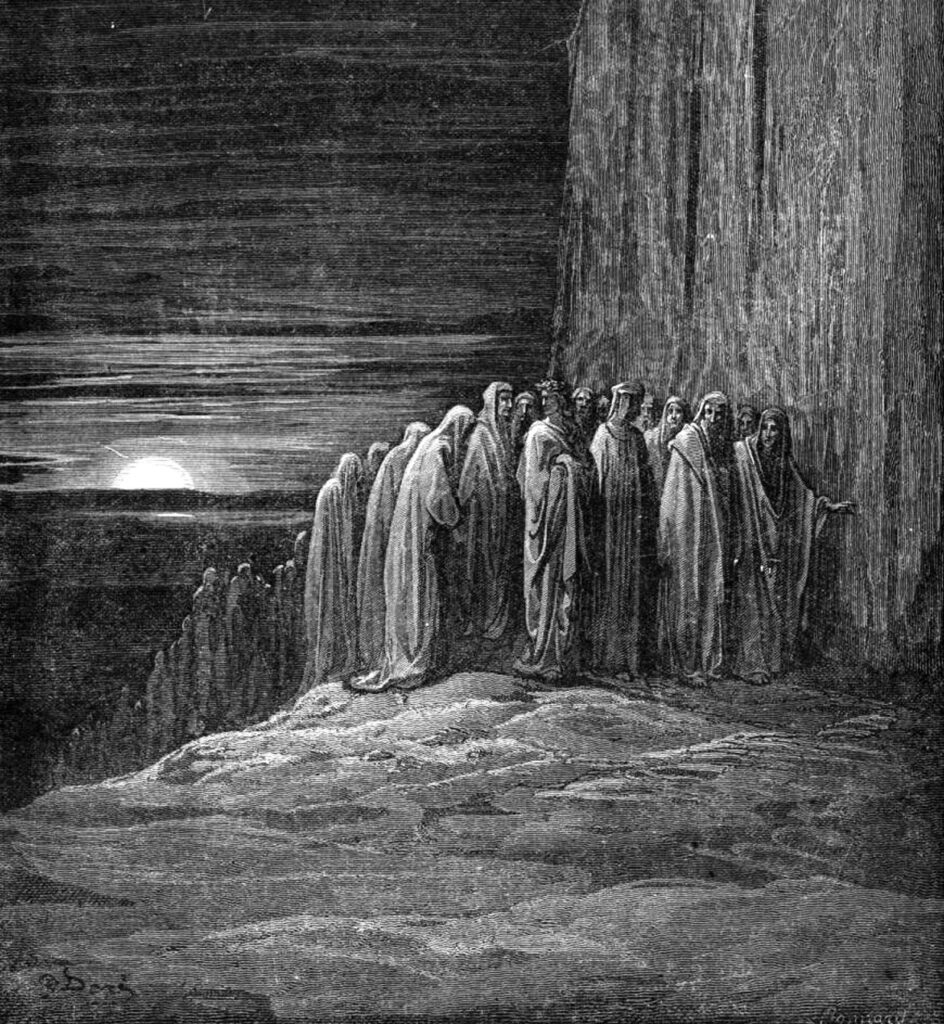

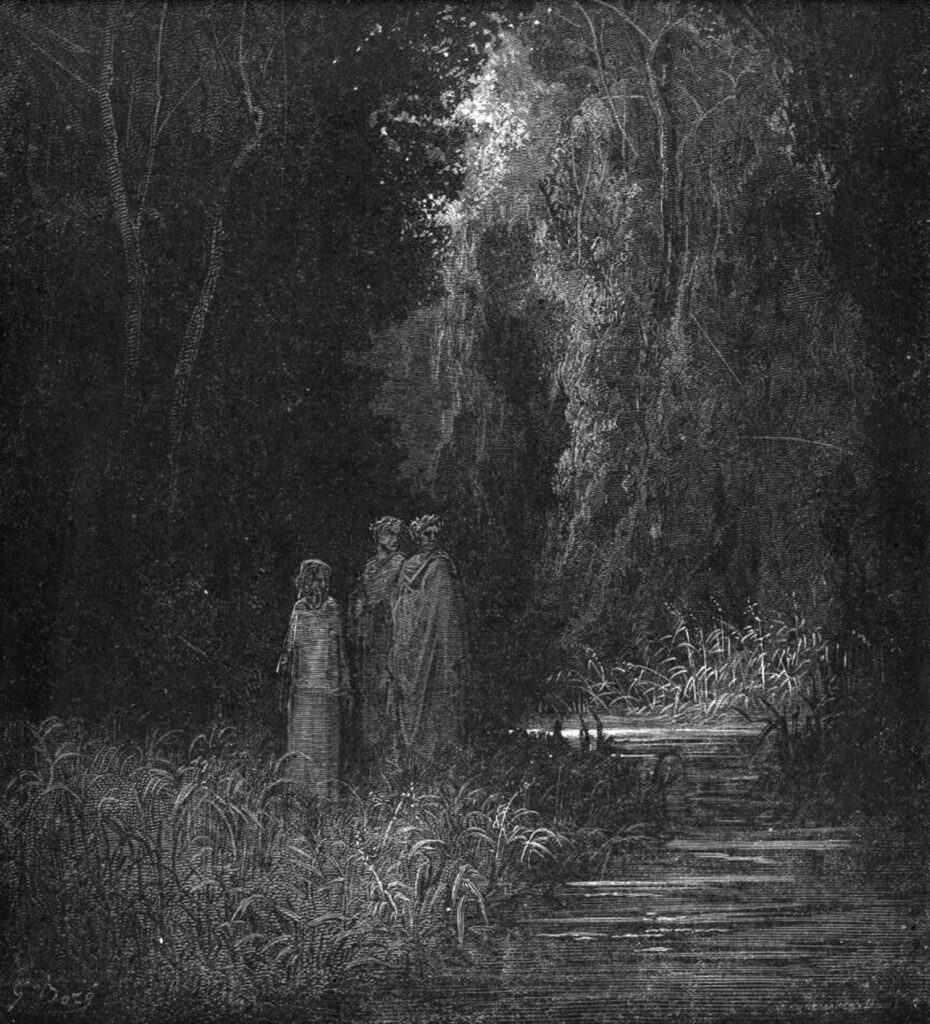

“Purgatorio” begins with Dante and Virgil emerging from the infernal regions to behold the stars once again, symbolizing hope and divine guidance. They find themselves at the foot of the Mountain of Purgatory on Easter morning, signifying resurrection and new beginnings. The poem is structured as an ascent up the mountain, with each terrace purging a specific sin through penance uniquely tailored to its nature.

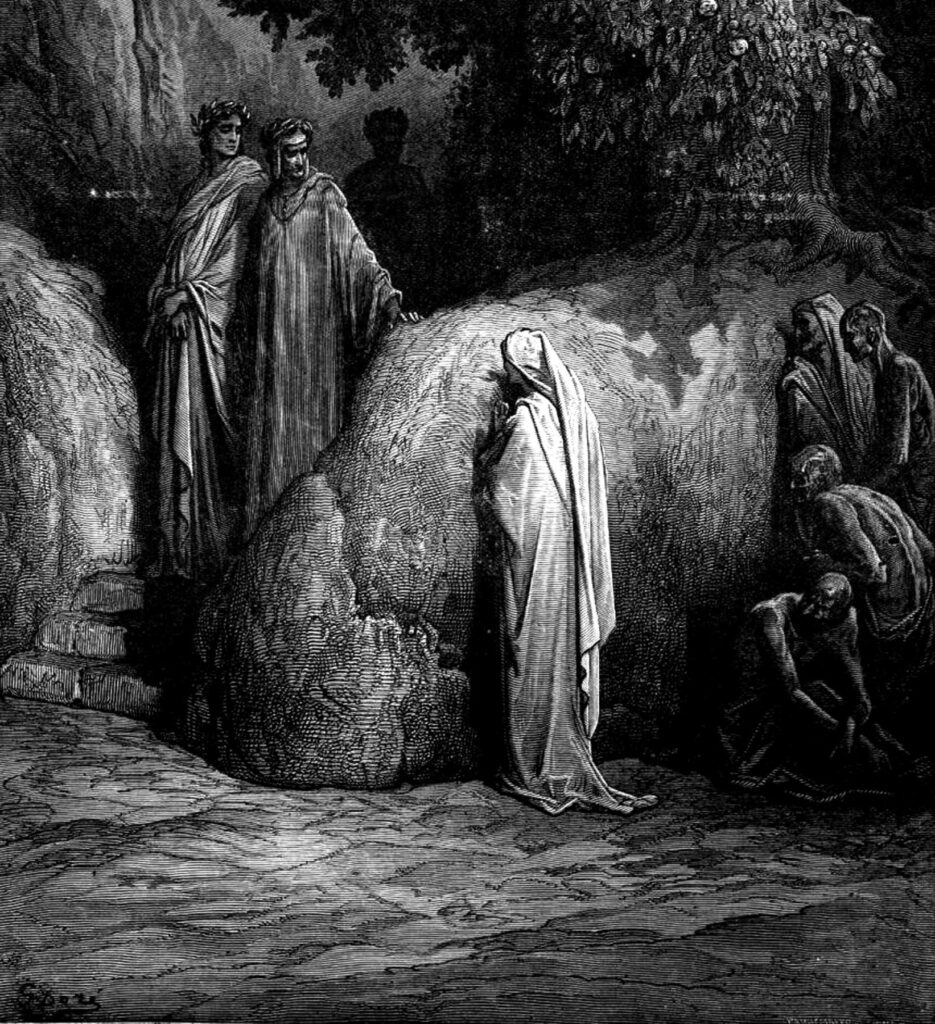

The journey begins at the shores of the island, where the souls who delayed their repentance until the end of their lives arrive, eager to begin their purification. Dante and Virgil meet Cato of Utica, a guardian of Purgatory, who instructs them on how to proceed.

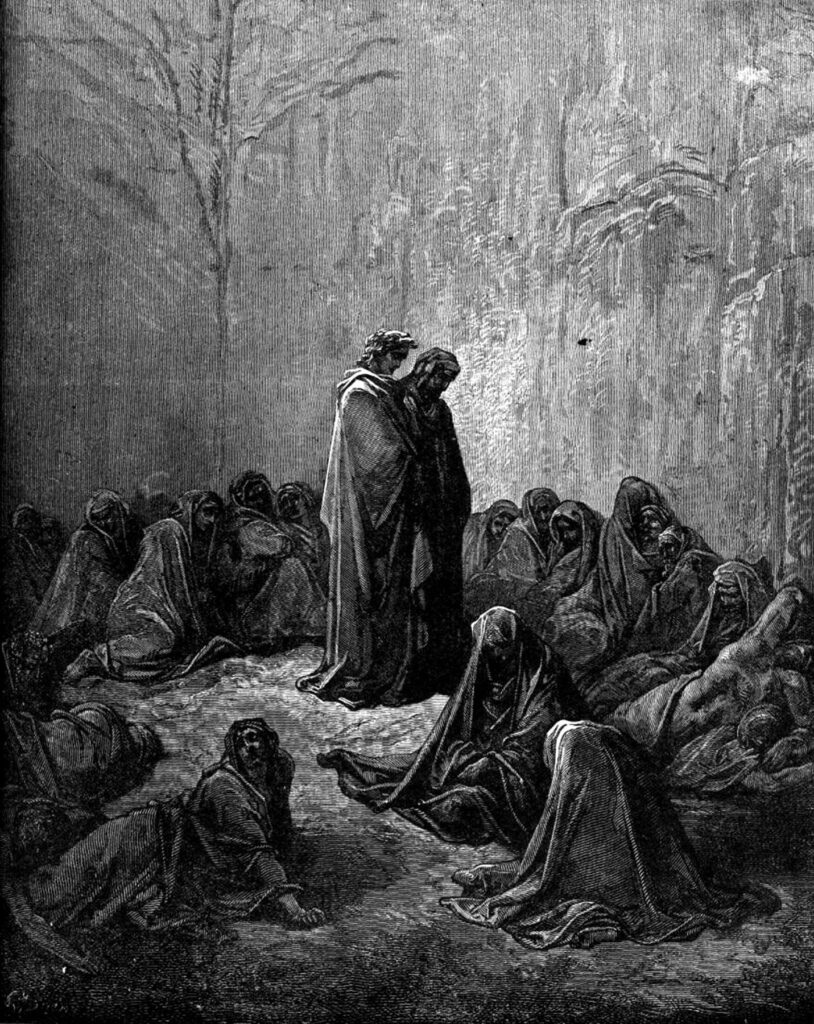

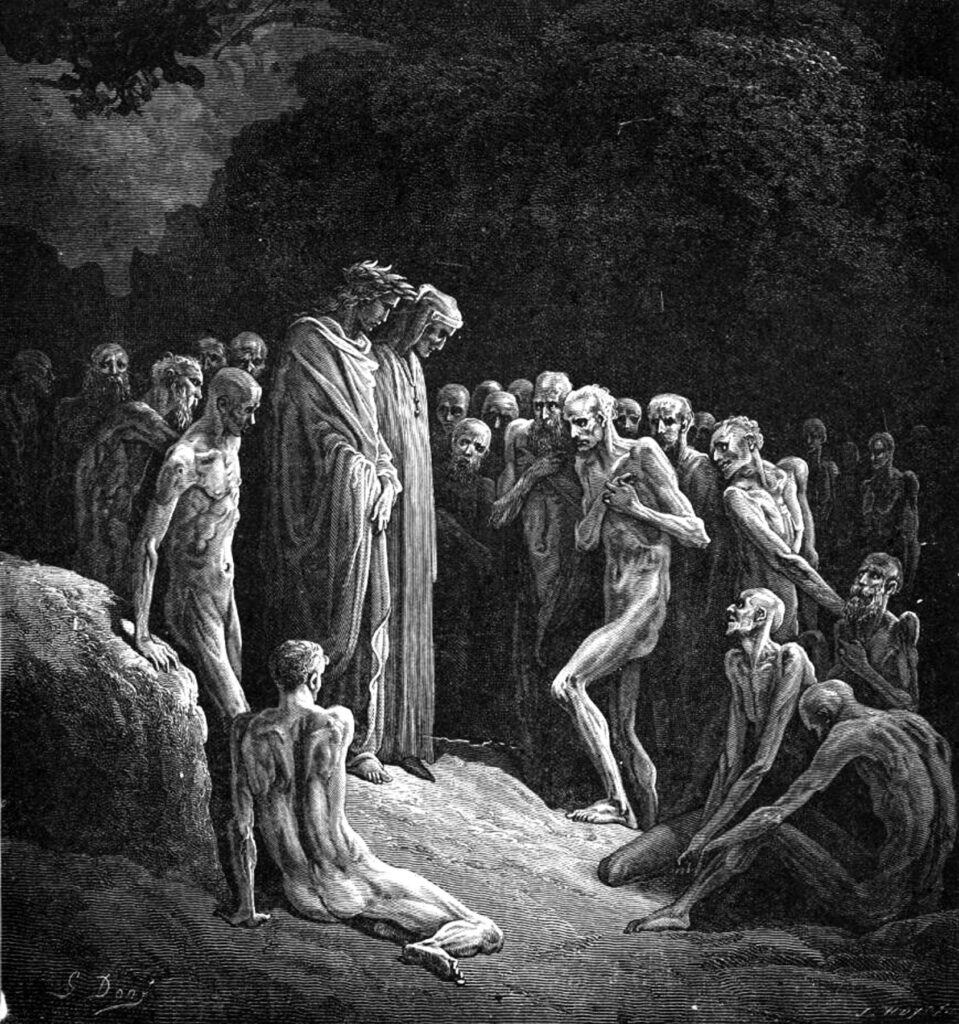

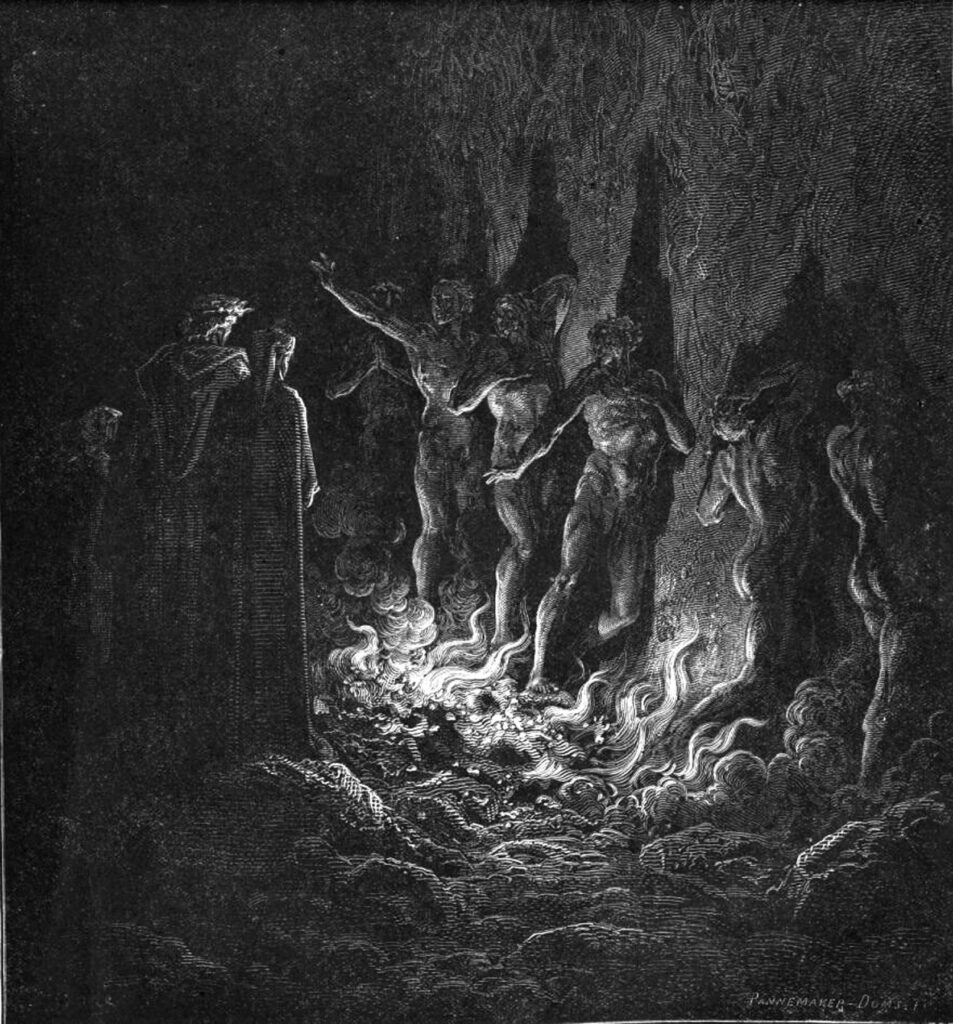

As they ascend, Dante encounters souls suffering penance for the sins of pride, envy, wrath, sloth, avarice, gluttony, and lust. These souls willingly endure their punishments as they reflect on their earthly sins and learn the virtues that counteract them. Notable is the transformation in the nature of the punishments, which, unlike the torments of Hell, are corrective and restorative rather than punitive.

Throughout “Purgatorio,” Dante the pilgrim undergoes significant spiritual growth, learning from the examples of the penitent souls and contemplating the nature of sin and redemption. His encounters with various historical and mythological figures continue to provide commentary on contemporary Italian politics, the nature of art and poetry, and the complexities of human virtue and vice.

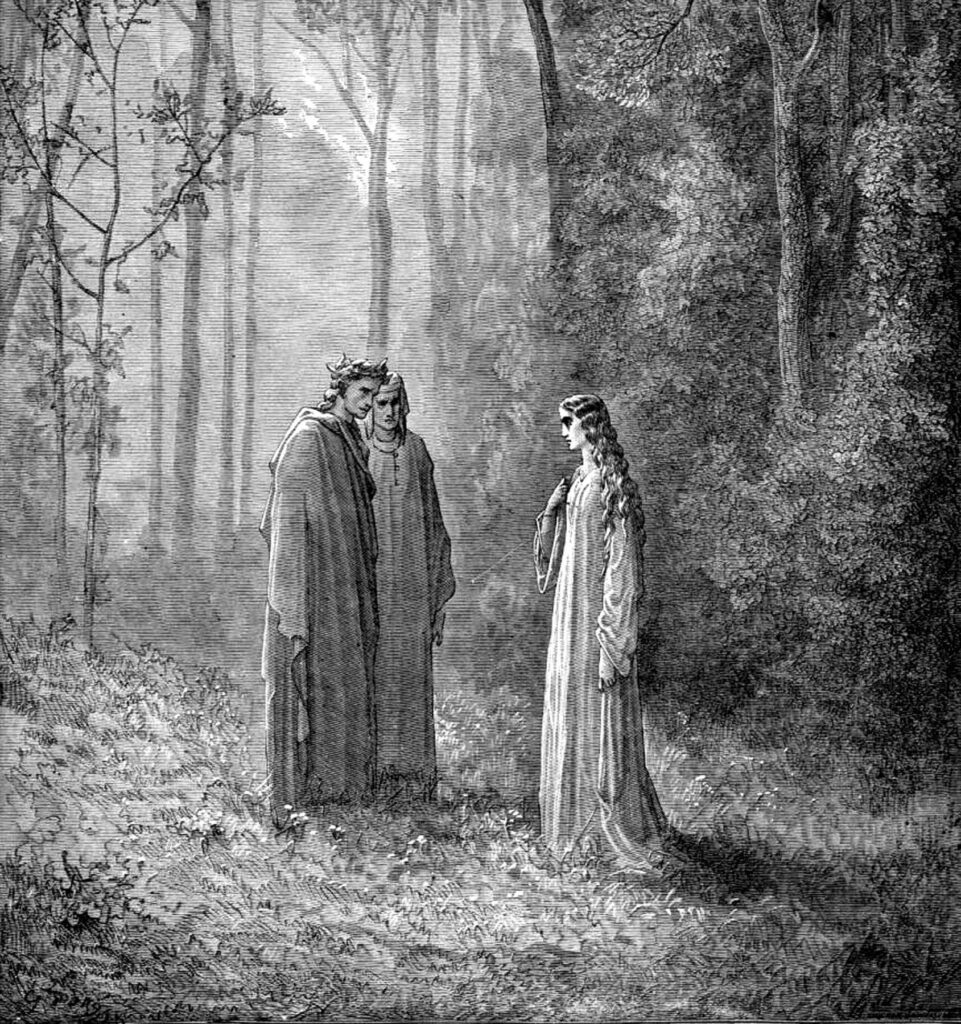

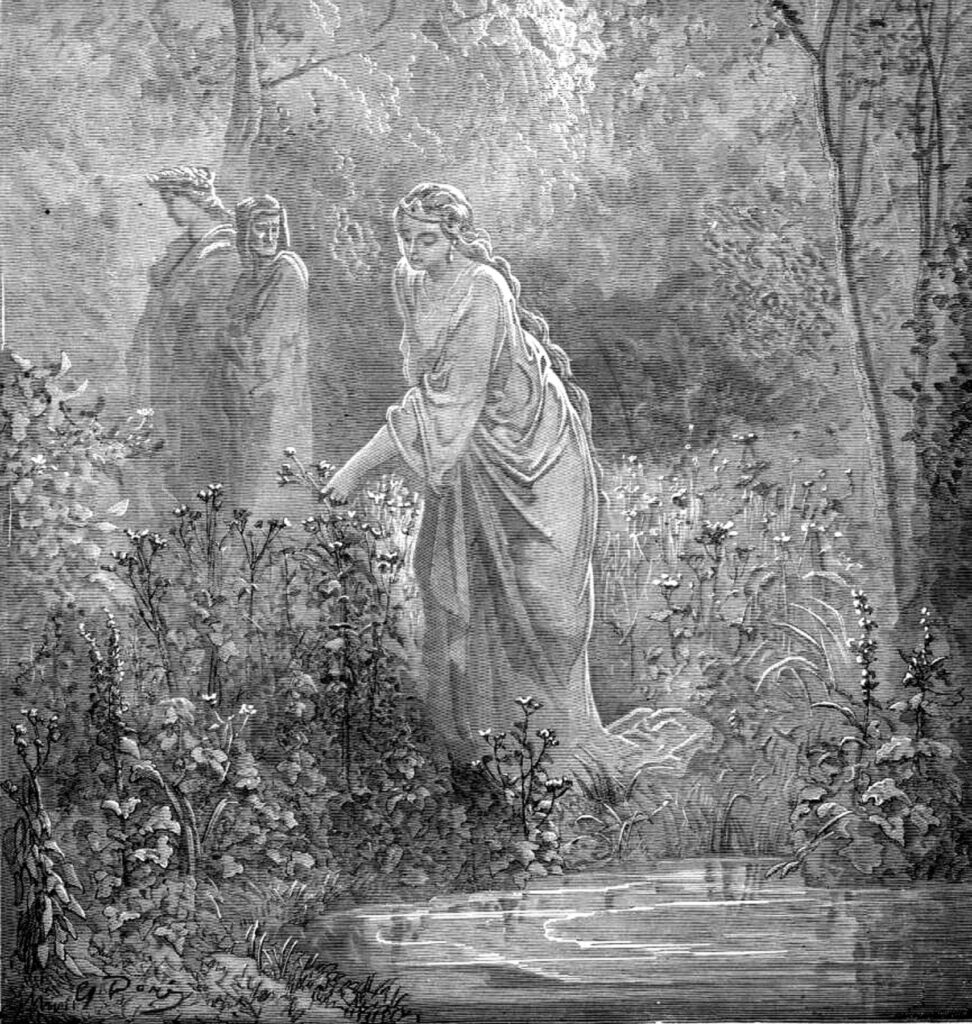

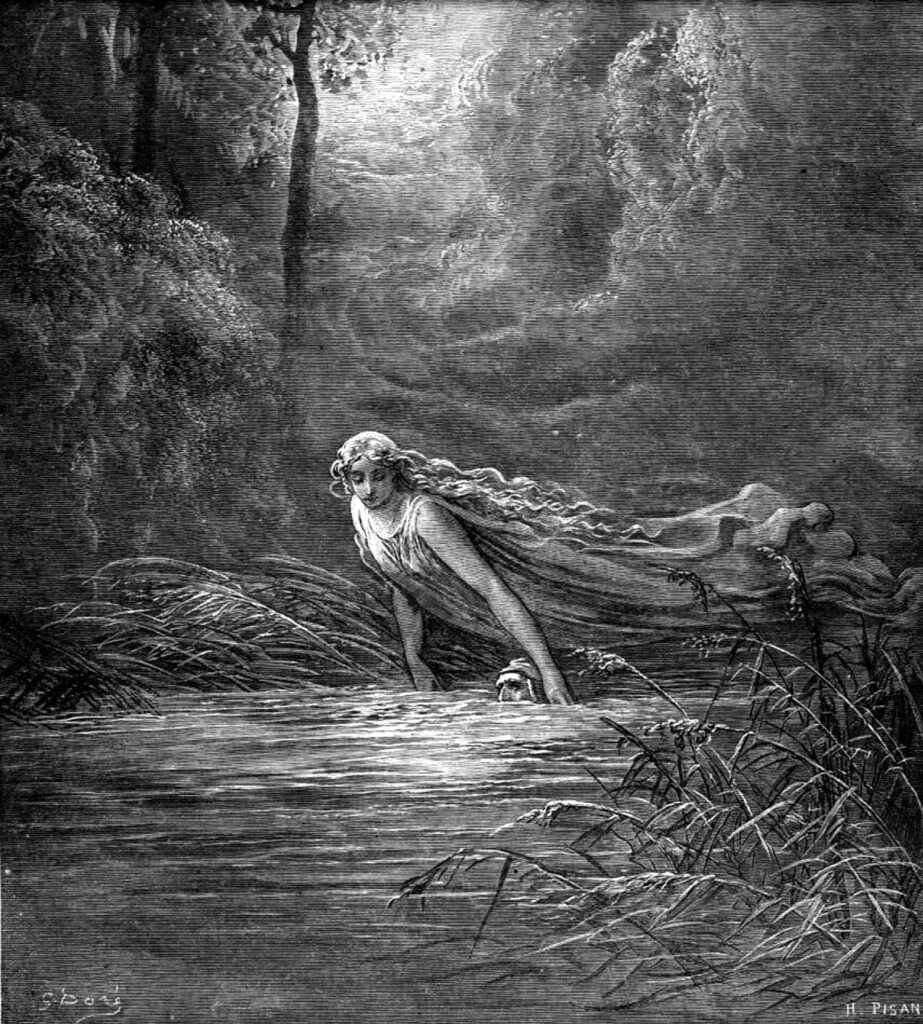

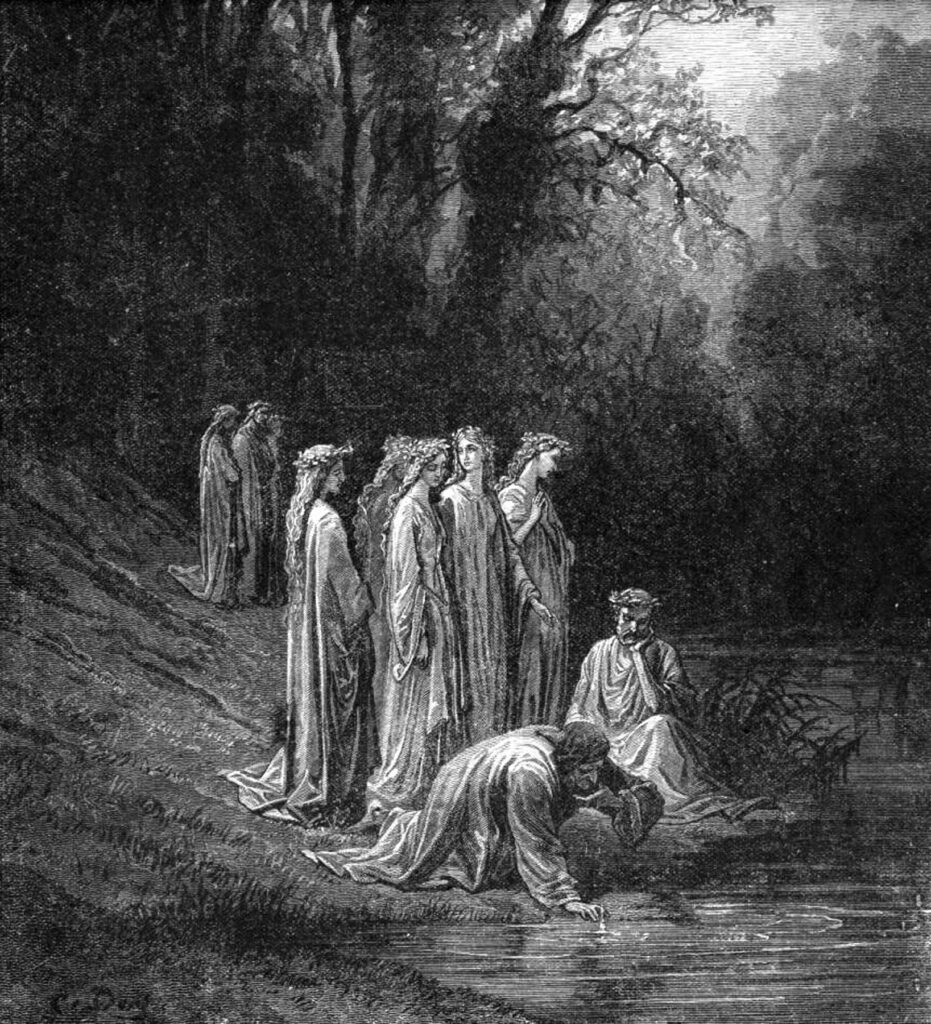

The summit of the mountain is the Earthly Paradise or the Garden of Eden, where Dante is cleansed in the waters of the Lethe, erasing the memory of his sins, and the Eunoe, which enhances the memory of his good deeds. Here, Virgil, representing human reason, must leave Dante’s side, as he cannot enter Paradise. Dante meets Beatrice, his lost love and the symbol of divine grace, who will guide him through the final realm of his journey—Paradise.

Canto I – The Shores of Purgatory

Ante-Purgatory | Dante and Virgil arrive on the shores of Purgatory, greeted by Cato. Cato instructs Virgil to clean Dante’s face and gird him with a reed, symbolizing humility. They begin their journey up the mountain, leaving behind the dark forest of Hell.

Canto I, the second part of his Divine Comedy, marks the transition from the despair of Hell to the hopeful journey through Purgatory, where souls are purified before their ascent to Paradise. This canto sets the stage for the spiritual regeneration and moral reformation that Purgatory symbolizes, reflecting themes of repentance, divine justice, and the possibility of redemption.

The canto opens with Dante and his guide, the Roman poet Virgil, emerging from Hell to see the stars once again, signifying hope and divine guidance. They find themselves at the shore of a mountainous island, the Mount of Purgatory, the only land in the southern hemisphere according to medieval cosmology. The shift from the dark, infernal regions to the serene, starlit landscape of Purgatory signifies a transition from sin to the potential for salvation.

As Dante and Virgil commence their ascent, they encounter Cato of Utica, a Roman statesman and stoic philosopher who serves as the guardian of the shores of Purgatory. Cato’s presence is significant; despite being a pagan, he is depicted as a virtuous soul, embodying the ideals of liberty and moral integrity. His role as a guardian emphasizes the themes of discipline and moral rectitude required for the souls undergoing purification.

Cato questions Virgil about their journey and, upon learning of their divine sanction, instructs them to cleanse Dante’s face and gird him with a reed, symbolizing humility and readiness for the purgatorial ascent. This act of cleansing and preparation signifies the shedding of earthly vanities and the initial steps towards spiritual purification.

The imagery in Canto I is rich with symbolic meaning:

The Stars: The visibility of stars, obscured in Hell, symbolizes divine grace and guidance, as well as the eternal nature of the soul’s journey towards God.

The Reed: The humble reed, which Virgil girds around Dante, contrasts with the proud and rigid reeds often used for crowns, emphasizing the importance of humility in the soul’s purification.

Cleansing: The act of washing Dante’s face with dew and girding him with a reed symbolizes the initial purification necessary for entering Purgatory, representing repentance and the renunciation of past sins.

Dante’s Emotional and Spiritual State

Dante’s reactions throughout Canto I reflect his emotional and spiritual transformation. The sight of the stars fills him with hope, contrasting with the despair he felt in Hell. His encounter with Cato, and his compliance with the rituals of cleansing and preparation, demonstrate his willingness to undergo the arduous process of purification. Dante’s humility and acceptance of divine will are crucial themes that will be further explored throughout “Purgatorio.”

Canto I serves as a narrative and thematic bridge between the despair of “Inferno” and the hope of “Purgatorio.” It introduces key themes of repentance, moral integrity, and the potential for redemption, setting the tone for Dante’s journey through the purifying realms. The canto emphasizes the importance of divine grace, humility, and the willingness to undergo spiritual renewal, preparing the reader for the complex exploration of human sin and redemption that follows.

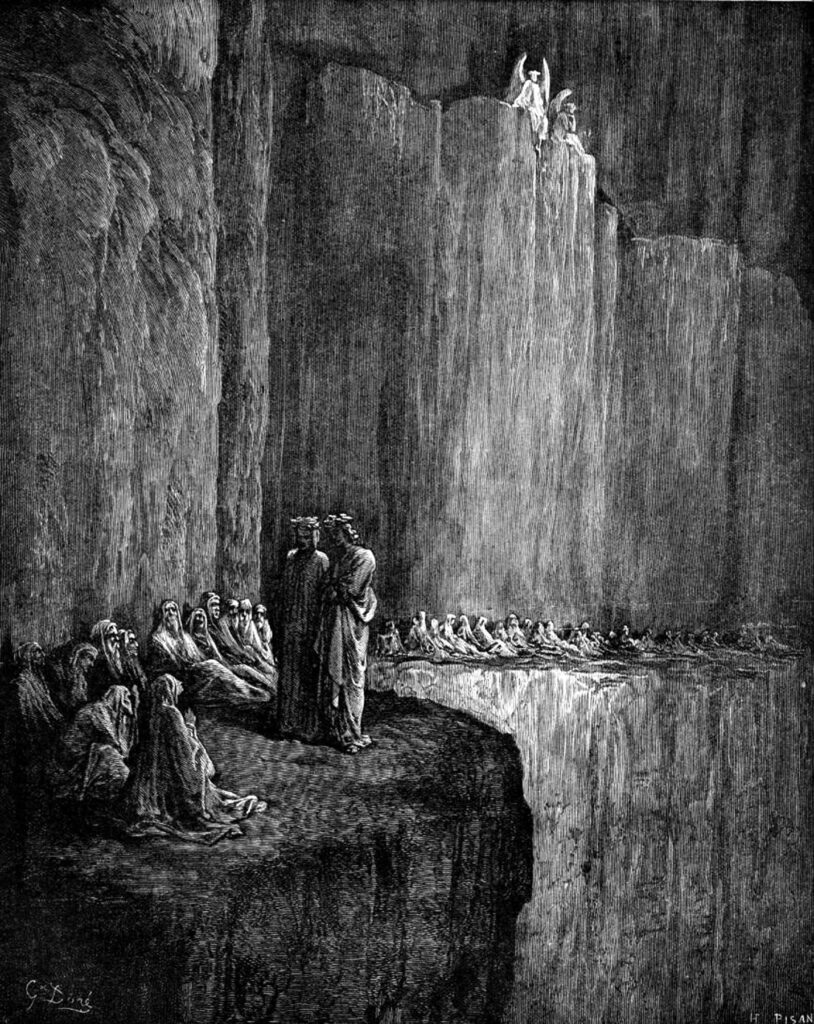

Canto II – The Angel Boatman

Ante-Purgatory | Dante and Virgil meet souls arriving by boat, guided by the Angel Boatman. Among them is Dante’s friend, Casella, who sings a hymn to comfort Dante. Cato admonishes them to continue their ascent, reminding them of their purpose.

Canto II of Dante’s “Purgatorio” is rich with themes of repentance, divine mercy, and the intercession of the saints, set against the backdrop of Dante’s continued journey through Purgatory. As the second canto of this middle section of “The Divine Comedy,” it bridges the initial awe and relief of escaping Hell with the rigorous process of purification that lies ahead for Dante and the souls in Purgatory.

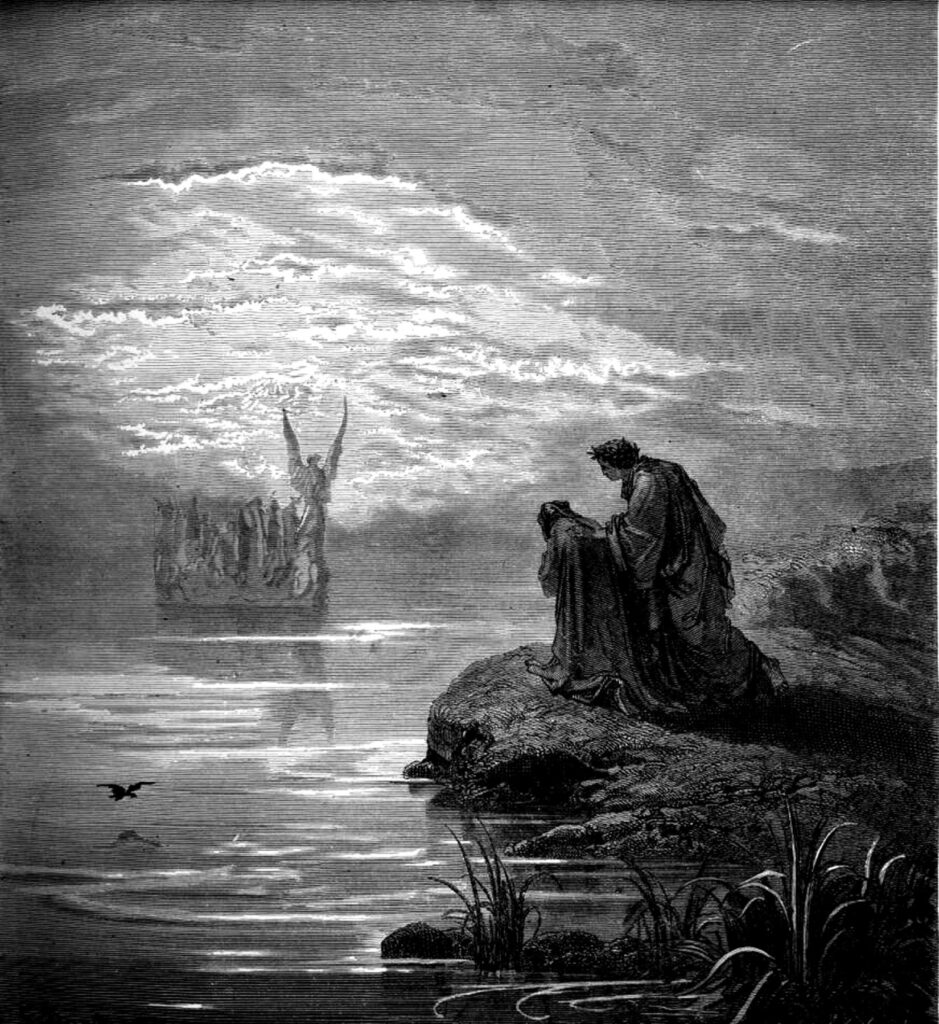

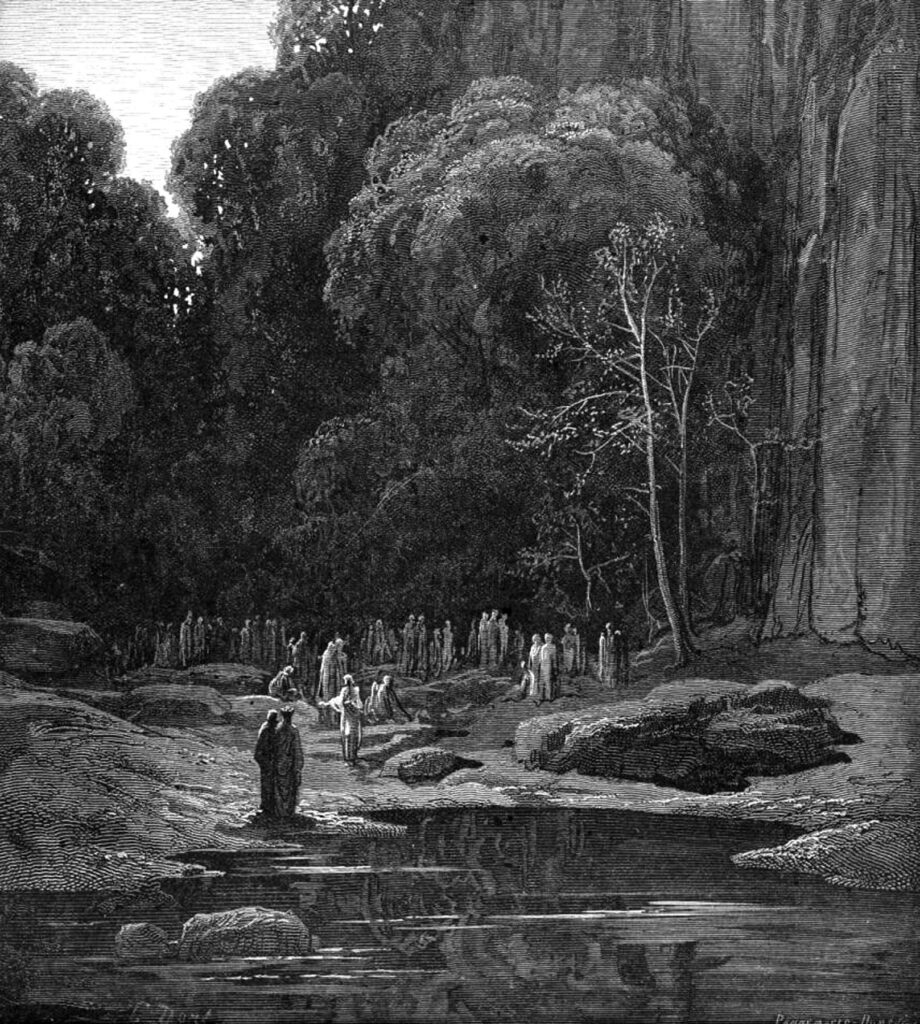

The canto opens with Dante’s invocation to the Muses, signaling the transition from the infernal to the purgatorial and highlighting the shift in tone and content. It is dawn on Easter Monday, and Dante, along with his guide Virgil, stands at the base of the Mount of Purgatory. The time and setting are significant, symbolizing rebirth and the beginning of a new phase in Dante’s spiritual journey.

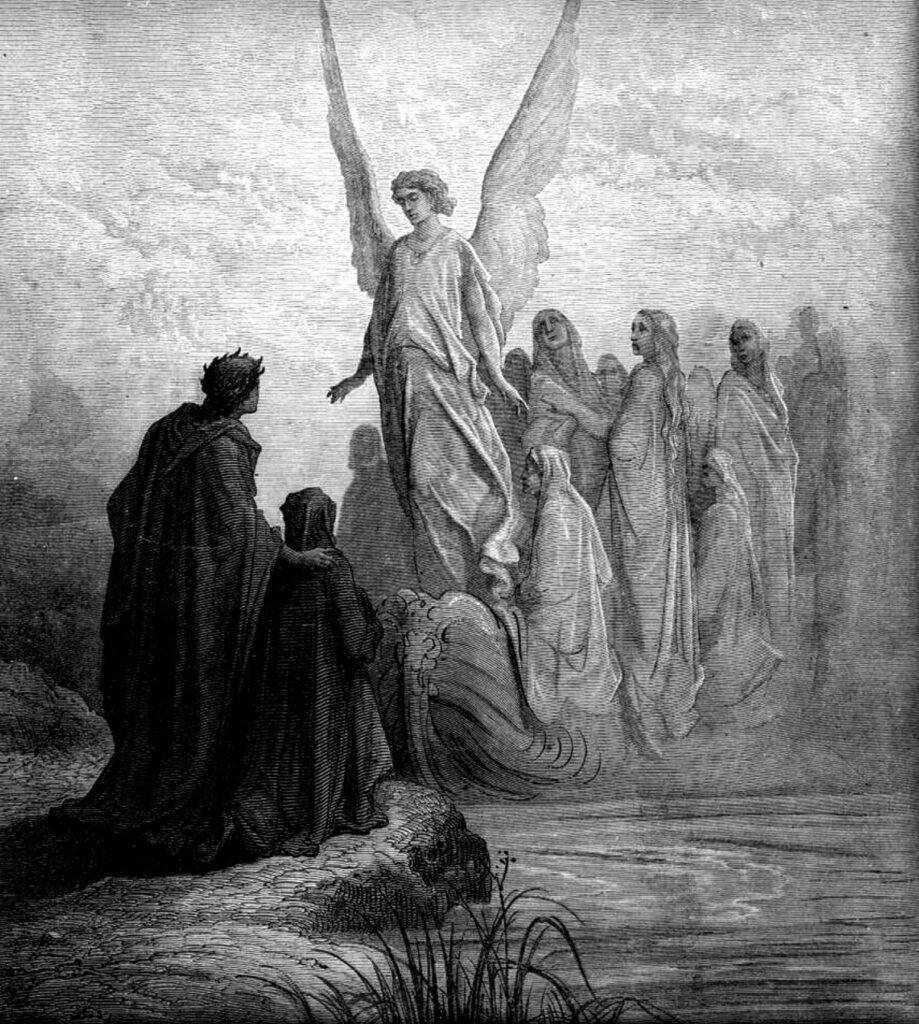

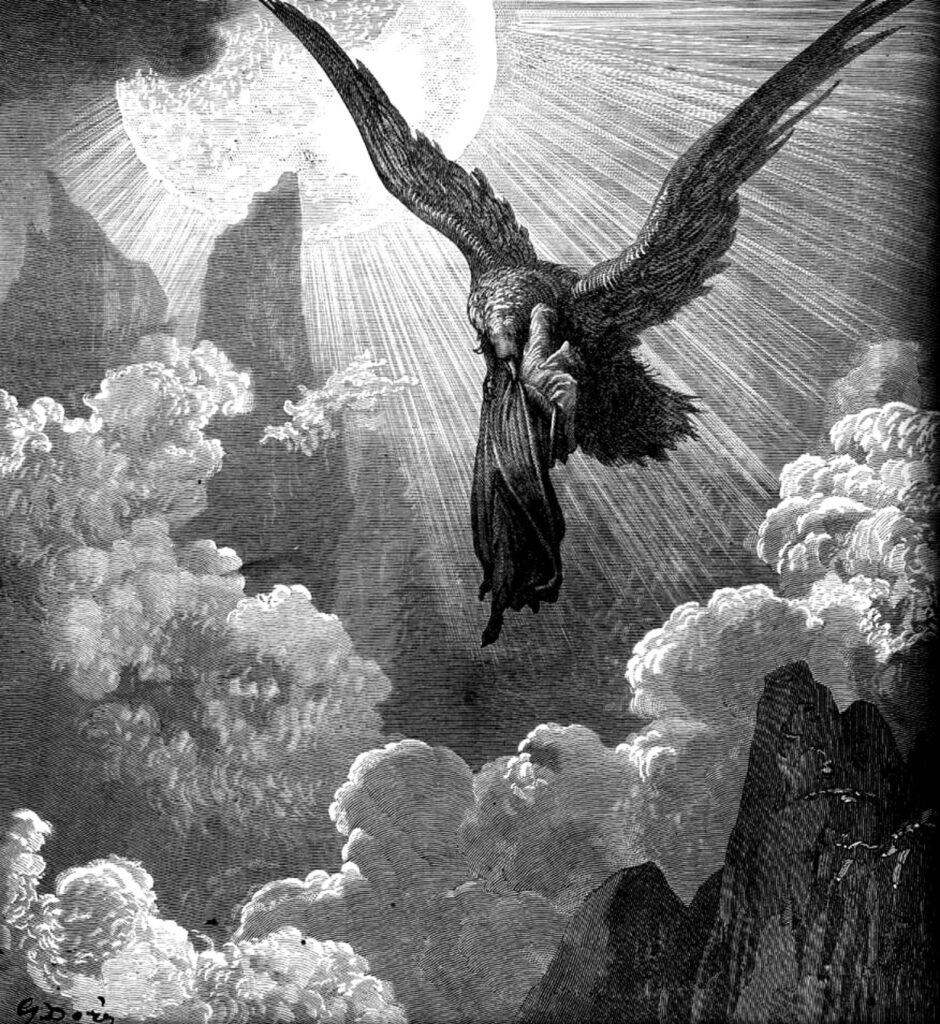

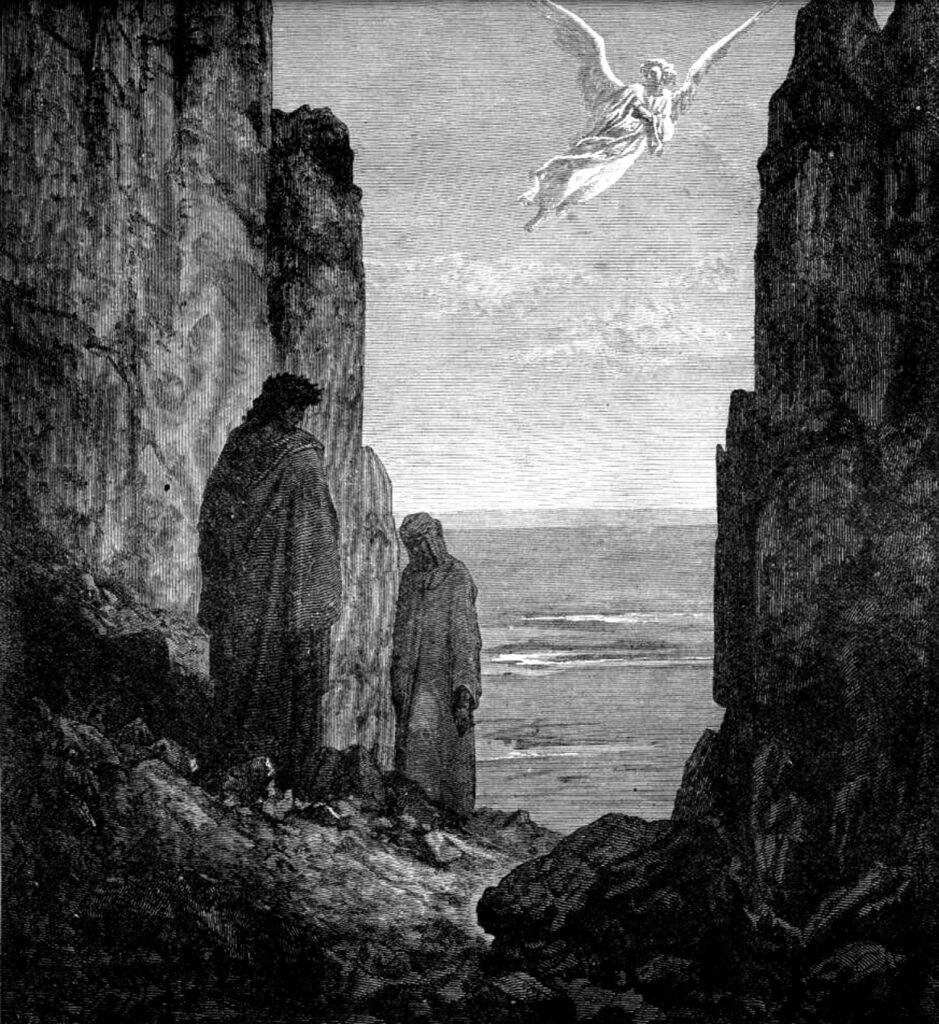

As Dante and Virgil converse, they observe a light moving swiftly across the water towards them. This light is a divine messenger, an angel piloting a boat filled with souls who have repented at the last moment of their lives. The angel’s approach, with the water undisturbed by the boat, symbolizes the grace and ease with which divine mercy operates.

The souls disembark, singing Psalm 114, “In exitu Israel de Aegypto,” which reflects their liberation from the bondage of sin, akin to the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt. Among these souls is Casella, a musician and friend of Dante’s, who represents the familiar and personal connection that Dante maintains with the earthly realm even as he traverses the spiritual world.

Dante asks Casella to sing, and Casella chooses a song that Dante himself wrote, a love song that speaks of desire for divine grace. This moment of earthly beauty and artistry serves as a temporary respite for the souls and Dante, highlighting the power of art to elevate the spirit and provide comfort, even in the context of spiritual purification.

The serene moment is interrupted by Cato, who rebukes them for indulging in the song, reminding them of the urgency of their purgatorial journey. This encounter emphasizes the disciplined nature of Purgatory, where even lawful pleasures must be set aside in favor of spiritual progress.

Prompted by Cato’s words, the souls, including Dante and Virgil, move towards the mountain to begin their ascent. The canto concludes with the souls eager to commence their purification, underscoring the theme of willing participation in one’s own redemption.

Canto II of “Purgatorio” is laden with symbolism and thematic depth:

- Divine Mercy: The arrival of the angel and the souls on the boat symbolizes God’s mercy towards those who repent, even at the last moment of their lives.

- Art and Beauty: Casella’s song represents the enduring value of beauty and art, which can inspire and uplift the soul, yet must be balanced with the need for spiritual discipline.

- Intercession: The presence of the angel and the responsiveness of the divine to the prayers of the living for the dead underscore the interconnectedness of the earthly and the divine, and the power of prayer and intercession.

Canto II sets the stage for the arduous and hopeful journey through Purgatory, characterized by themes of repentance, the tension between earthly beauty and spiritual discipline, and the ever-present mercy and grace of the divine. Through the experiences of Dante and the souls he encounters, the canto explores the complex interplay between human desire, divine justice, and the transformative power of penance.

Canto III – The Valley of the Rulers

Ante-Purgatory | The poets encounter excommunicated souls in Ante-Purgatory. Manfred, King of Sicily, reveals his story and explains that those who repent at the last moment must wait before entering Purgatory proper. Dante learns about the justice of divine mercy.

Canto III continues the journey of Dante and Virgil as they begin their ascent of the Mountain of Purgatory. This canto delves into themes of repentance, the nature of divine justice, and the role of free will in the soul’s journey toward redemption. It is here that Dante encounters the souls of the late repentant who, due to various reasons, postponed their repentance until the end of their lives.

The canto opens with Dante and Virgil approaching the gate of Purgatory, which serves as the official entrance to the mountain where souls are purified. The gate is guarded by an angel, who is described as having a sword that seems to emit no light, signifying perhaps the discerning nature of divine judgment that is not meant to harm but to illuminate truth and righteousness.

Before the gate, Dante notices an inscription calling for those who seek purification to summon the angelic gatekeeper. The entrance features three steps, each symbolizing different stages of repentance and spiritual readiness. The first step, made of polished, reflective marble, symbolizes self-examination and the recognition of one’s sins. The second, cracked and darkened, represents contrition and sorrow for sins. The third, made of red porphyry and symbolizing the blood of Christ, represents the love that motivates true repentance and the sacrifice necessary for redemption.

The angelic gatekeeper marks Dante’s forehead with seven “P”s, representing the seven peccati (sins) or poenitentiae (penances) that must be purged on the mountain. This act signifies the beginning of Dante’s active participation in the purgatorial process of cleansing and purification.

As Dante and Virgil enter, they encounter the souls of those who repented at the last moment of their lives, particularly those who were excommunicated from the Church. These souls must wait outside the purgatorial gate for a period thirty times longer than their period of contumacy, unless shortened by prayers from the living. This emphasizes the poem’s recurrent theme of the efficacy of prayers for the dead and the interconnectedness of the earthly and spiritual realms.

Among these souls, Dante meets Manfred, the King of Sicily and the son of Emperor Frederick II, who tells his story of excommunication and his death in battle. Despite his excommunication and the manner of his death, Manfred expresses hope in God’s mercy, revealing that contrition and the love of God can transcend the Church’s earthly judgments. Manfred’s request that Dante inform his daughter, Constance, of his fate underscores the theme of communication between the living and the dead and the potential for prayers to aid souls in Purgatory.

Canto III is rich with symbolism and theological themes:

- Repentance and Contrition: The three steps to the gate of Purgatory symbolize the stages of repentance, emphasizing the importance of self-awareness, sorrow for sin, and the love that motivates true repentance.

- Divine Mercy and Justice: The angelic gatekeeper and the inscription on the gate underscore the balance between God’s mercy and justice, inviting all who seek purification to enter.

- Intercession: The souls of the excommunicated, particularly Manfred, highlight the role of prayers from the living in aiding the souls in Purgatory, suggesting a communion between the Church Militant (on Earth) and the Church Suffering (in Purgatory).

Canto III sets the stage for Dante’s journey through the mountain of purification, emphasizing the themes of repentance, divine mercy, and the power of prayer. Through encounters with symbolic elements and souls like Manfred, Dante’s narrative explores the complexities of sin, redemption, and the hope that lies in God’s boundless compassion and justice.

Canto IV – The Slothful on the Terrace of Pride

Ante-Purgatory | Dante and Virgil climb arduously. Dante speaks with Belacqua, a soul delayed in Ante-Purgatory for his indolence. The arduous ascent symbolizes the effort required to overcome sloth and achieve spiritual progress, emphasizing the need for diligence.

Canto IV delves deeper into the spiritual journey of purification, as Dante and his guide Virgil ascend the Mountain of Purgatory. This canto is rich with themes of enlightenment, repentance, and the gradual shedding of earthly concerns in pursuit of divine grace. It is here that Dante begins to confront the nature of love and free will as central to the process of purification.

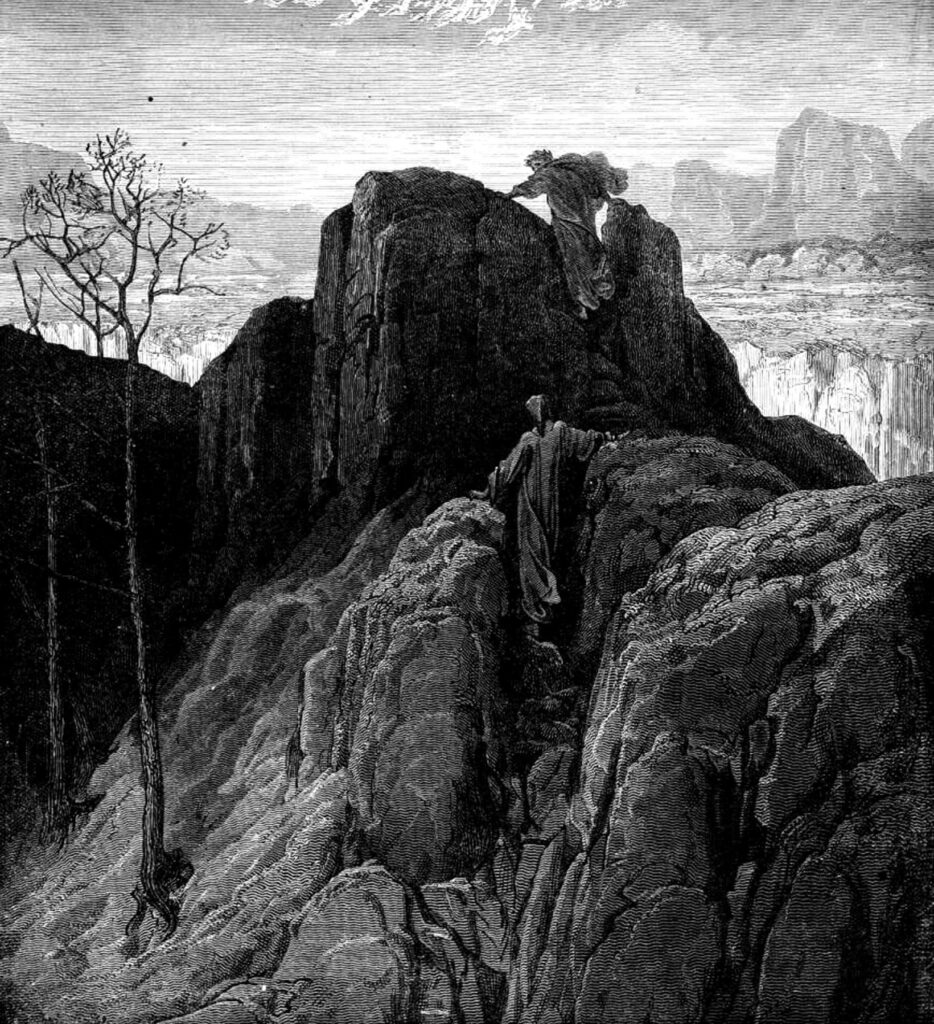

As they continue their climb, Dante feels the weight of his earthly body, contrasting with the ease of the souls in Purgatory, who are unburdened by physical constraints. This highlights the pilgrim’s unique status as a living visitor to the afterlife realms and underscores the theme of the arduous nature of spiritual growth and self-improvement.

Dante and Virgil encounter the soul of Belacqua, a lute maker and acquaintance of Dante from Florence, who is sitting in a lazy posture, shaded by a rock. Belacqua represents the souls who delayed their repentance until the last possible moment, due to negligence or procrastination, and must now wait an extended period before beginning their active purification on the mountain. His position and demeanor reflect his slothful attitude towards spiritual salvation during his earthly life.

Belacqua explains to Dante that his delayed ascent is due to the divine decree that the time a soul must wait before beginning purification corresponds to the time of their procrastination in repentance. However, this waiting period can be shortened by the prayers of the living, reinforcing the poem’s emphasis on the interconnectedness of the earthly and spiritual realms and the efficacy of prayer.

The conversation between Dante, Virgil, and Belacqua delves into the theological underpinnings of Purgatory’s justice system. It is clarified that no soul would wish to remain in their current state longer than necessary, as each soul inherently desires to move closer to God. This desire reflects the transformative nature of Purgatory, where the souls, though suffering, are aligned in their ultimate goal of purification and union with the divine.

The canto touches on the crucial role of free will in the process of repentance and salvation. The souls in Purgatory are those who, despite their sins, chose ultimately to turn towards God, highlighting the theme of love as the driving force behind true repentance and redemption. This prepares the reader for the deeper exploration of love, free will, and virtue that Dante will undertake as he ascends the mountain.

Despite Belacqua’s discouraging words, Dante is urged by Virgil to continue the journey, emphasizing the importance of perseverance and the active pursuit of grace. The canto closes with the poets resuming their ascent, symbolizing the ongoing nature of the soul’s journey toward enlightenment and the necessity of personal effort in achieving spiritual growth.

Canto IV offers profound insights into the nature of repentance, the dynamics of divine justice, and the importance of free will and love in the pursuit of salvation. Through Dante’s interactions with the souls he meets, particularly Belacqua, the canto explores the consequences of spiritual negligence and the transformative potential of purgatorial suffering. The themes of prayer, community, and the active pursuit of virtue are woven throughout, underscoring the canto’s contribution to the overarching narrative of redemption and grace.

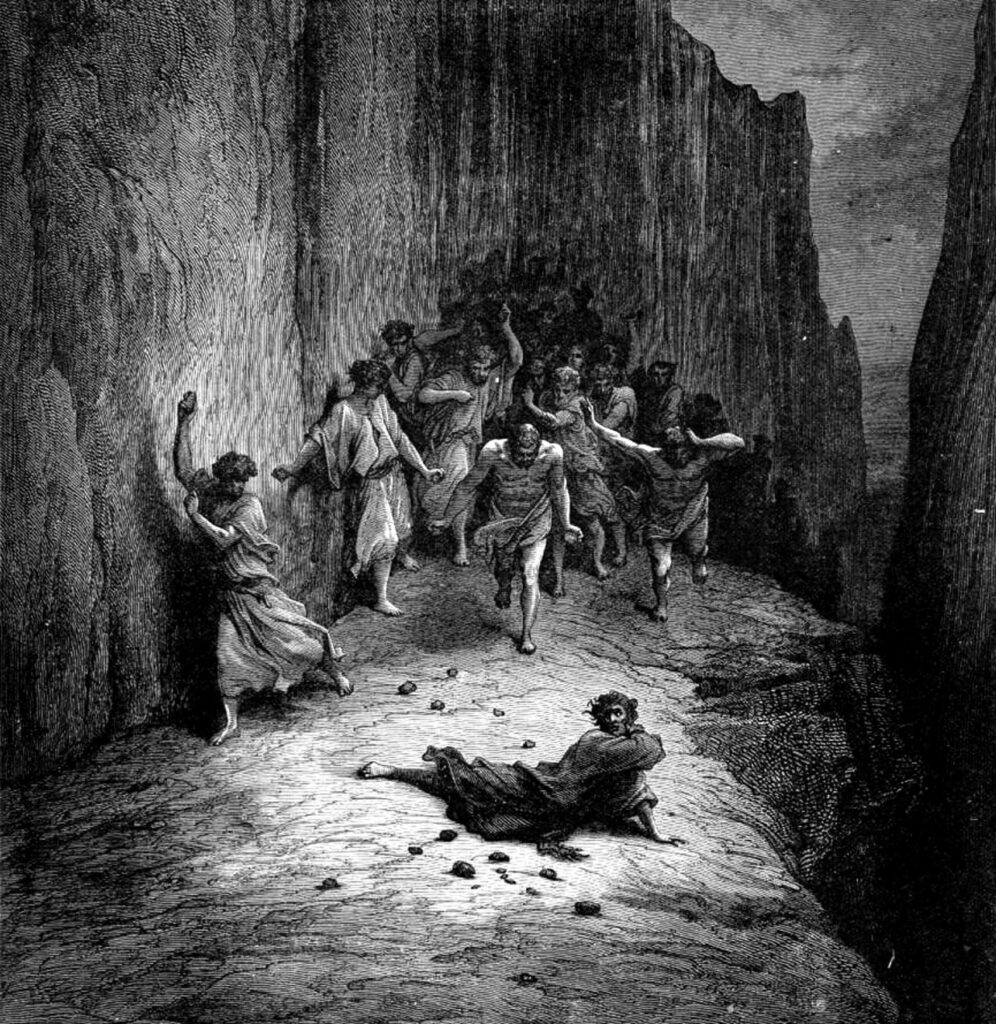

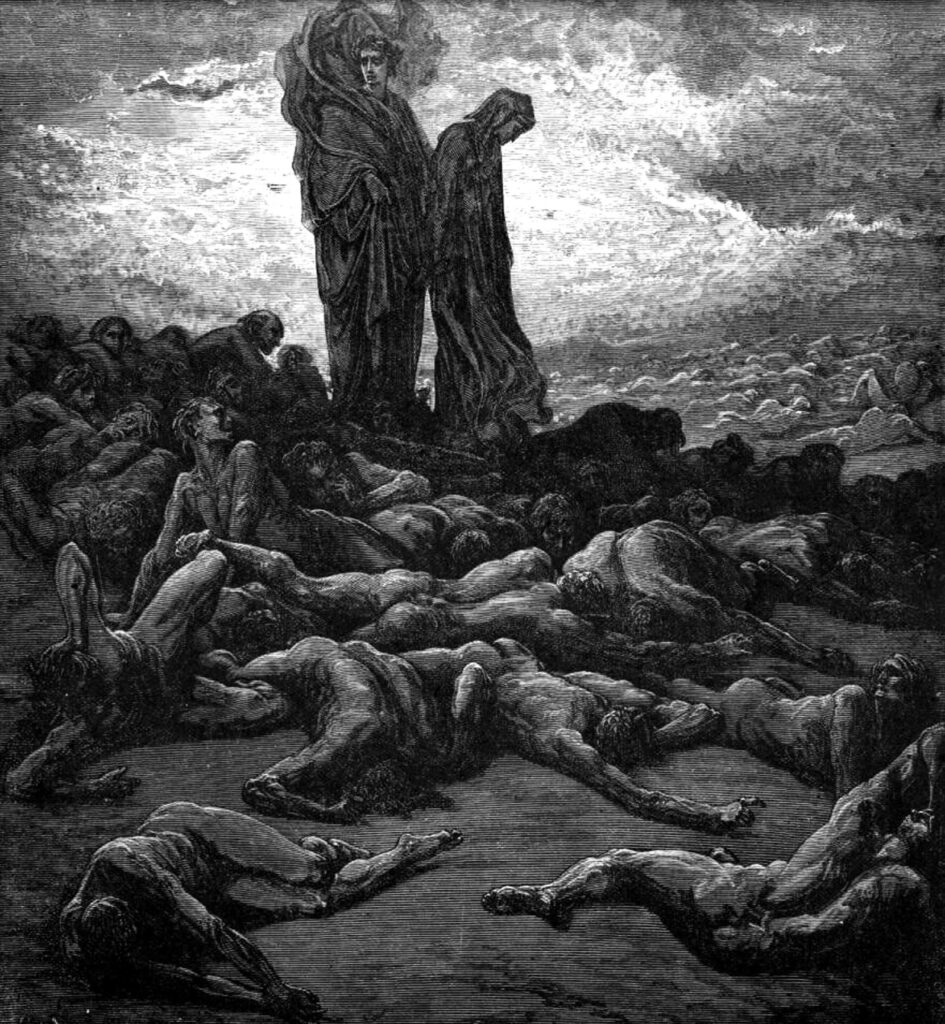

Canto V – The Repentant Souls

Ante-Purgatory | Dante meets souls who died violently and repented at the last moment. They recount their stories and ask Dante to remember them. The canto explores themes of sudden death, repentance, and the hope for salvation even in dire circumstances.

Canto V of Dante’s “Purgatorio” continues to explore themes of repentance and divine mercy, focusing on the souls of those who repented at the very end of their earthly lives. This canto delves into the power of genuine contrition, the efficacy of prayer, and the nuanced understanding of time and divine justice in the afterlife.

Dante and Virgil ascend to the second terrace of Purgatory, where they encounter the souls of the late repentant—those who, due to various circumstances, postponed their repentance until the final moments of their lives. This terrace is dedicated to the purgation of the sin of sloth, characterized by a lack of timely action towards one’s salvation.

Among the souls they meet are examples of individuals who repented at the last possible moment:

- Jacopo del Cassero: A Guelph leader from Fano who was ambushed and mortally wounded. With his dying breaths, he turned his thoughts to God, seeking mercy.

- Buonconte da Montefeltro: The son of Guido da Montefeltro, known from Dante’s “Inferno.” Buonconte recounts his death in the battle of Campaldino, where a single tear of repentance and a call to the Virgin Mary ensured his place in Purgatory, despite his body being lost to the elements.

- La Pia: A noblewoman from Siena, whose brief and cryptic account hints at her death possibly being caused by her husband. Her story emphasizes the importance of remembering and praying for the souls in Purgatory.

The narratives of these souls underscore the theme of God’s boundless mercy, which can redeem even those who repent in their final moments. The canto contrasts the divine understanding of justice and time with human perceptions, suggesting that sincere repentance, regardless of its timing, holds significant weight in the divine economy of salvation.

The souls express a desire to be remembered in the prayers of the living, highlighting the communal aspect of salvation and the belief in the living’s ability to aid the souls in Purgatory through prayer and remembrance. This intercession reflects the interconnectedness of the earthly and spiritual realms and the collective journey towards God.

In response to Dante’s inquiries, Virgil elaborates on the nature of love and free will, foundational themes in “Purgatorio.” He explains that love, either rightly or wrongly directed, is the force behind all actions. This discourse sets the stage for the deeper exploration of love as the driving force behind both virtue and sin, emphasizing the importance of aligning one’s love with divine will.

The encounters with the souls on this terrace prompt Dante to reflect on the fleeting nature of life and the eternal implications of one’s earthly choices. The stories of sudden and untimely deaths serve as a reminder of life’s unpredictability and the urgency of repentance and spiritual alignment with God’s will.

Canto V offers profound insights into the themes of repentance, divine mercy, and the communal aspects of salvation. Through the poignant stories of the late repentant souls, Dante presents a narrative that affirms the possibility of redemption through sincere contrition and the power of prayer. The canto, rich with theological and philosophical discourse, reinforces the notion of love as the fundamental force guiding human actions towards either salvation or damnation, setting the groundwork for the pilgrim’s continued journey of purification and moral growth.

Canto VI – The Arrival of Sordello

Ante-Purgatory | Dante converses with Sordello, who laments the political situation in Italy. Sordello guides them to the Valley of the Rulers, where souls of rulers pray for divine intervention. The canto critiques the political strife and corruption of Dante’s time.

Canto VI delves into themes of political justice, the nature of true repentance, and the communal responsibility towards righteousness, both on Earth and in the afterlife. This canto is particularly notable for its reflection on Italy’s political turmoil and Dante’s longing for righteous governance, intertwined with the process of purification that souls undergo in Purgatory.

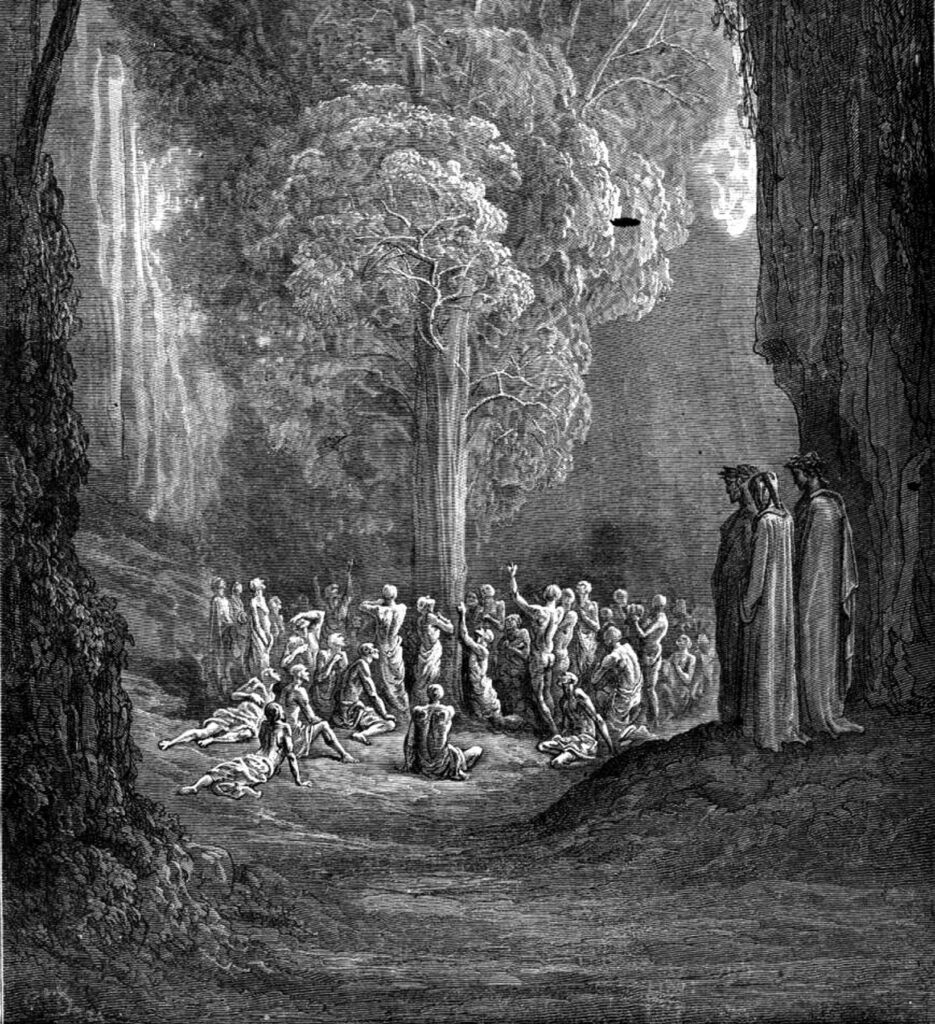

As Dante and Virgil continue their ascent through Purgatory, they find themselves on the terrace of the slothful, where souls expiate the sin of acedia (spiritual sloth or apathy). This terrace is marked by the fervent pace of the souls as they circle the mountain, embodying the zeal and diligence they lacked in life. Their chants and prayers reflect themes of fervor and the consequences of sloth on spiritual progress.

The souls on this terrace recite examples of diligence and zeal from Scripture, such as the zeal of Mary, the mother of Jesus, in her visitation to Elizabeth, and the promptness of the Romans. These recitations serve as both penance and instruction, emphasizing the virtues that counteract sloth.

Amidst the encounters with the penitent souls, Dante pauses to lament the state of Italy, which he personifies as a woman in distress due to the lack of justice and peace within its city-states and the church’s involvement in temporal affairs. Dante’s critique is a poignant reflection on the political disarray and moral corruption of his time, revealing his deep concern for the well-being of his homeland and his longing for divine intervention to restore order and righteousness.

Dante and Virgil encounter the soul of Sordello, a fellow Italian poet from Mantua, who is shocked to learn of Dante’s journey through the afterlife while still alive. Sordello’s reaction underscores the extraordinary nature of Dante’s pilgrimage and the divine favor that enables it. This meeting also highlights the bond of shared identity and language, as Sordello warmly embraces Virgil upon learning of their common heritage from Mantua.

Sordello engages in a discourse on the nature of repentance and negligence, elaborating on the conditions that lead souls to Purgatory and the varying lengths of their purgation based on the timing and sincerity of their repentance. This discussion further illuminates the theological underpinnings of Purgatory, where the will to repent and the actions taken in life directly impact the soul’s journey towards purification.

As evening approaches in Purgatory, Dante observes the unique phenomenon where darkness falls, marking the end of the day’s journey for the souls and the pilgrims alike. Unlike Earth, where night signifies rest, in Purgatory, it brings a temporary halt to active penance, symbolizing the unceasing nature of divine justice and the continuous yearning for God’s presence.

Canto VI weaves together Dante’s critique of contemporary political and ecclesiastical failures with the ongoing theme of repentance and purification in the afterlife. Through the lens of the slothful penitents and Dante’s poignant reflections on Italy, the canto explores the consequences of moral and spiritual apathy, both individually and collectively. The encounters with the souls, particularly Sordello, serve to deepen Dante’s understanding of divine justice and mercy, reinforcing the poem’s overarching narrative of redemption and the transformative power of divine love.

Canto VII – The Sunset on the Mountain

Ante-Purgatory | Sordello leads Dante and Virgil to the valley’s entrance, where they encounter the souls of kings and rulers. These souls must learn humility before ascending. The canto reflects on the responsibilities of leadership and the need for just governance.

Canto VII continues to explore the themes of repentance, divine justice, and the dynamics of love as the driving force behind human actions. Set against the backdrop of the terrace of the slothful, this canto delves deeper into the nature of love, free will, and the consequences of misdirected desires.

As Dante and Virgil proceed, they encounter souls fervently reciting examples of sloth and its opposite virtue, zeal. The souls’ chants illustrate the importance of prompt and vigorous action in service to God and others, contrasting with the sin of sloth, which is characterized by a lack of spiritual ardor and negligence in pursuing the good.

The highlight of Canto VII is Virgil’s profound discourse on love, prompted by Dante’s inquiries. Virgil explains that love is the natural inclination of all beings and is the source of all actions, whether good or evil. He distinguishes between love directed toward noble ends, which leads to virtue, and love that seeks base or harmful ends, resulting in vice. This exposition lays the groundwork for understanding the sins punished in Purgatory as distortions or misapplications of love.

- Innate Love: Virgil elucidates that love toward the primary good and the fundamental desire for happiness is innate in every being. This form of love cannot err, as it is directed toward the ultimate good.

- Elective Love: The errors arise in the elective love, where free will comes into play. The soul may err in choosing its object of love due to a lack of proper knowledge or a willful rejection of the good.

Virgil emphasizes the critical role of reason and free will in guiding love towards rightful ends. While love itself is a natural force, the proper exercise of free will and reason ensures that love is directed towards virtuous and noble pursuits. This interplay between love, free will, and reason underscores the moral framework within which the souls in Purgatory operate, striving to rectify their misdirected loves through penance and purification.

The canto also revisits the encounter with Sordello, who continues to serve as a guide for Dante and Virgil. Sordello’s presence highlights the themes of political and moral commentary, as he mourns the state of Italy and its cities, echoing Dante’s earlier lamentations about the lack of justice and peace in his homeland.

Sordello leads Dante and Virgil to the Valley of Princes, where rulers and leaders who neglected their spiritual well-being for worldly concerns reside. This valley serves as a precursor to the higher terraces of Purgatory, emphasizing the consequences of misdirected love and the neglect of one’s duties towards God and others.

Canto VII provides a rich theological and philosophical exploration of the nature of love and its implications for human morality and spiritual growth. Through Virgil’s discourse, Dante presents a nuanced understanding of love as the foundational force behind all actions, highlighting the importance of aligning one’s loves with divine will. The encounters with the souls and the presence of Sordello reinforce the poem’s recurring themes of repentance, the interplay between free will and divine grace, and the longing for righteous leadership and peace in the earthly realm. This canto serves as a pivotal point in Dante’s journey, deepening his understanding of the principles that govern the process of purification and redemption in Purgatory.

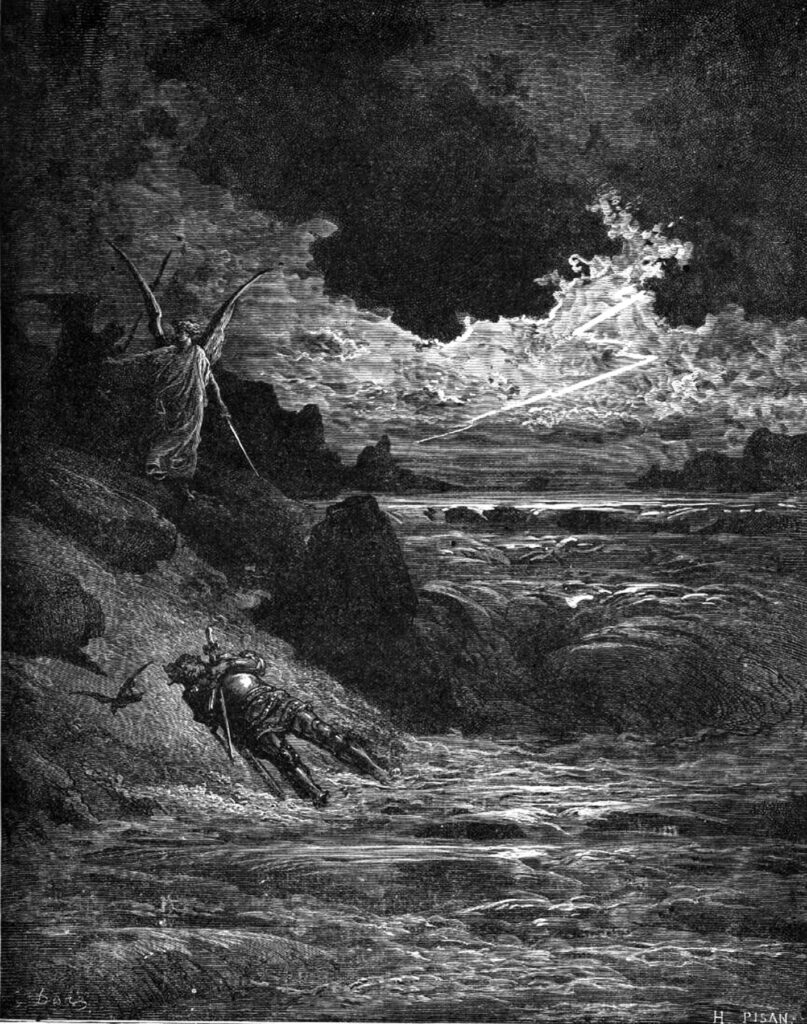

Canto VIII – The Angel of Humility

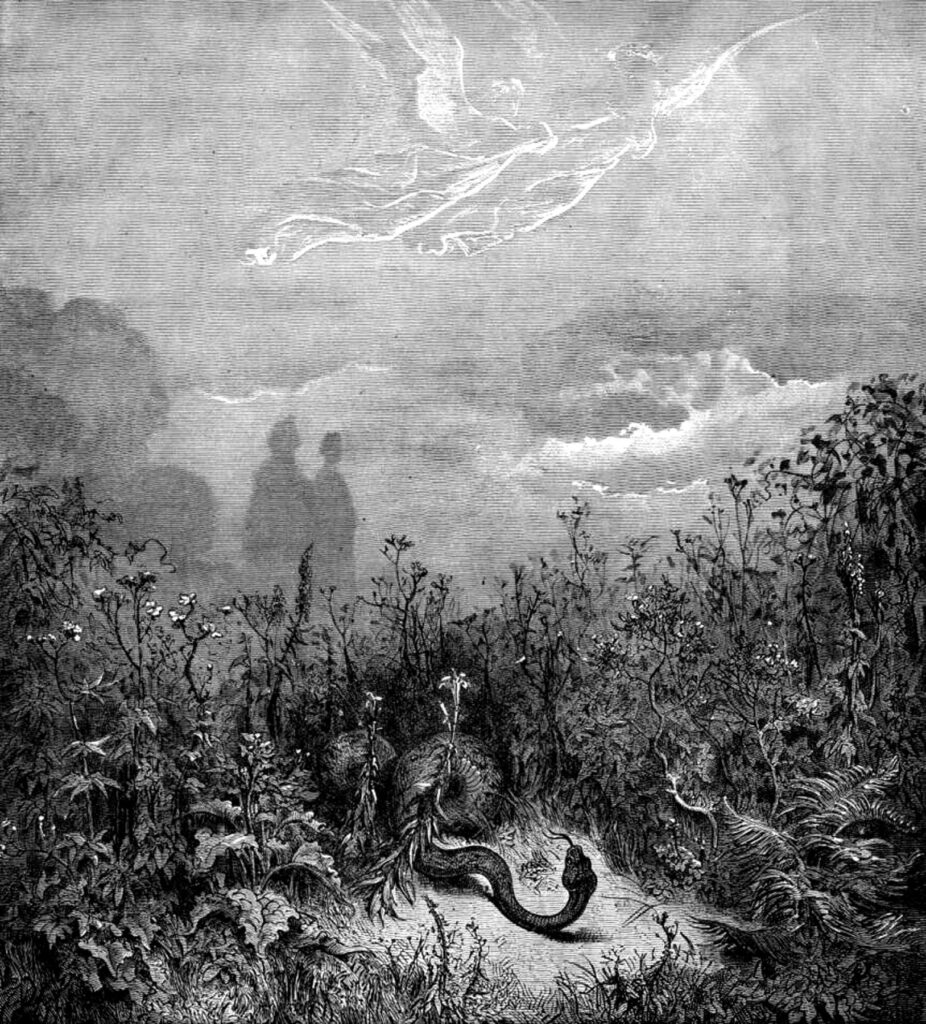

Ante-Purgatory | The poets spend the night in the valley. An angel arrives, singing, and drives away a serpent. The souls sing a hymn of praise. The canto emphasizes the importance of vigilance, divine protection, and communal worship in the journey of purification.

Canto VIII is set in the twilight hours on the shores of Purgatory, marking a transition from the day’s journey to the night’s vigil. This Canto is pivotal as it underscores the themes of repentance, divine justice, and the communal aspect of the souls’ journey towards salvation.

As the Canto opens, Dante and his guide Virgil are in the company of the souls of late repentant penitents who had delayed their confession and penance until the final moments of their lives. These souls, now in Ante-Purgatory, await their time to ascend the mountain proper for their purification. The setting sun casts a fading light over the scene, symbolizing the closing of a day but also the hope that comes with the impending night and the opportunity for reflection and prayer it brings.

Dante observes the serene and solemn atmosphere among the penitent souls, who are preparing for the angelic guardians to seal the gates of Purgatory as night falls. This ritual underscores the contrast between the divine order in Purgatory and the chaotic despair of Hell. The presence of the angels, with their flaming swords, serves as a protective barrier against the forces of evil, reminiscent of the guardians at the gates of Eden, emphasizing the theme of guarded innocence and the sanctity of the penitential process.

At this juncture, Dante encounters the shade of Sordello, a fellow Italian poet from Mantua, who, upon recognizing a countryman, embraces Dante warmly. This encounter underlines the poem’s emphasis on human connections and the shared journey of souls towards redemption. Sordello’s reaction to Virgil, whom he venerates as a master and guide, highlights the reverence for wisdom and guidance on the path to purification.

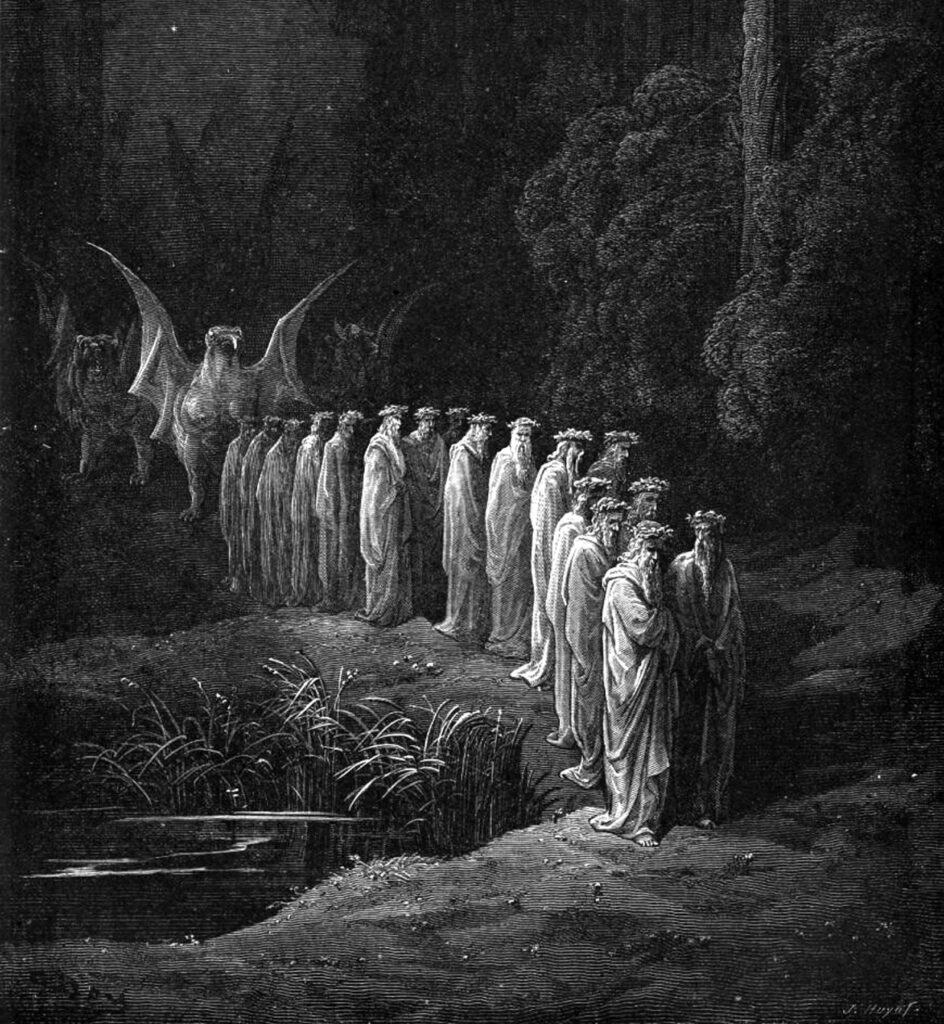

Sordello then leads Dante and Virgil to a vantage point from where they can observe the Valley of the Princes, a lush and verdant area where the souls of negligent rulers are purged of their sins of pride and ambition. This setting, imbued with natural beauty, symbolizes the mercy of God and the potential for renewal and redemption. The souls in this valley, despite their earthly power and status, now find themselves in a state of humility, singing the “Salve Regina” in unison, which reflects their collective longing for divine grace and intercession.

As night descends, the Canto culminates in a moment of communal prayer and vigilance. The protective angels circle the valley, safeguarding the penitent souls from the temptations that darkness might bring. This protective act reinforces the theme of divine watchfulness and care over the souls in Purgatory.

Canto VIII, therefore, is rich in symbolism and thematic depth, portraying the evening as a time of reflection, communal prayer, and divine protection. It highlights the transitional nature of Purgatory as a realm where justice is tempered with mercy, and where the communal aspect of penance and prayer aids in the souls’ journey towards salvation. Through vivid imagery and interactions among the characters, Dante explores the nuances of repentance, the importance of guidance and wisdom, and the overarching theme of divine grace that permeates the “Purgatorio.”

Canto IX – The Gate of Purgatory

Ante-Purgatory | Dante dreams of an eagle lifting him to the sphere of fire. He awakens at the gate of Purgatory, guarded by an angel. The angel carves seven P’s on Dante’s forehead, representing the seven deadly sins, and opens the gate with a key.

Canto IX is a pivotal segment in the narrative, showcasing the poet’s journey through the second realm of the afterlife, Purgatory. This canto is rich in symbolism, moral lessons, and theological insights.

The canto begins with Dante and his guide, Virgil, ascending the mountain of Purgatory. As they climb, Dante notices souls approaching them, and he inquires about their identity. Virgil explains that these souls are penitent souls who have repented of the sin of avarice, which is the excessive desire for material wealth. These souls are adorned in sackcloth and are led by an angel who warns them against the sin of pride.

Dante recognizes one of the souls among the penitents, Forese Donati, a friend from Florence who had died recently. Dante and Forese engage in a conversation, during which Forese expresses his joy at seeing Dante on the path of righteousness. He warns Dante about the dangers of pride and the importance of humility in the journey towards salvation.

As they continue their ascent, Dante encounters another soul, Bonagiunta da Lucca, a poet from the 13th century. Bonagiunta engages Dante in a discussion about poetry and literature, emphasizing the importance of spiritual enlightenment and divine inspiration in artistic creation.

The canto concludes with Dante expressing his gratitude to Bonagiunta and Forese for their guidance and encouragement. He reflects on the significance of their words and resolves to continue his journey with renewed determination and humility.

Through Dante’s encounters with Forese and Bonagiunta, Dante emphasizes the importance of moral and intellectual virtues in the journey towards salvation. The canto serves as a reminder of the transformative power of penance and the redemptive nature of divine grace.

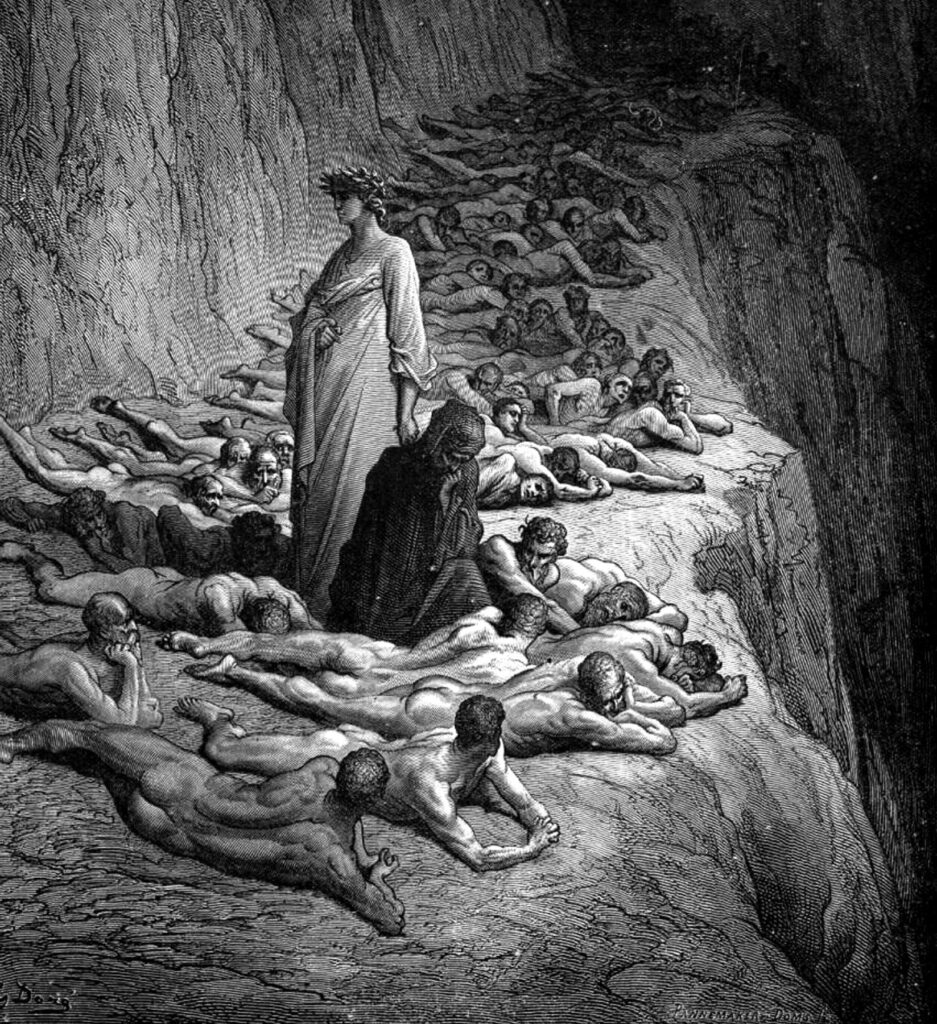

Canto X – The Sculptures of Humility

First Terrace: Pride | On the first terrace, the poets see magnificent carvings depicting examples of humility. The prideful souls are burdened with heavy stones, bowing their heads in humility. The canto highlights the transformative power of humility and divine artistry.

Canto X continues the poet’s journey through the second realm of the afterlife, Purgatory, where souls undergo purification to attain redemption. This canto is replete with allegorical elements, moral lessons, and theological symbolism.

The canto opens with Dante and Virgil encountering a group of souls who are suffering from the sin of wrath. These souls are enveloped in a dense fog that symbolizes the confusion and torment caused by their anger. Among them is Marco Lombardo, a nobleman from Lombardy, who engages Dante in a conversation about the nature of divine justice and free will.

Marco Lombardo expounds on the concept of free will, emphasizing its crucial role in determining one’s moral actions and destiny. He argues that human beings possess the freedom to choose between good and evil, and that God’s justice is predicated on this fundamental principle of moral agency.

As Dante listens to Marco’s discourse, he is struck by the profound insights into the workings of divine providence and the moral order of the universe. Marco’s teachings prompt Dante to reflect on his own spiritual journey and the importance of exercising virtuous behavior in accordance with divine law.

The canto also features a debate between Dante and Marco regarding the state of the world and the corrupting influence of worldly power and ambition. Marco laments the degradation of society and the prevalence of vice and injustice, while Dante expresses his hope for the restoration of moral order through divine intervention.

Towards the end of the canto, Dante and Virgil bid farewell to Marco Lombardo and continue their ascent up the mountain of Purgatory. As they progress, Dante reflects on the lessons he has learned from Marco’s teachings and resolves to persevere in his quest for spiritual enlightenment.

In Canto X, Dante delves into themes of free will, divine justice, and the moral responsibility of individuals in shaping their own destinies. Through his encounter with Marco Lombardo, Dante grapples with complex philosophical questions about the nature of human existence and the relationship between God and humanity. The canto serves as a profound meditation on the ethical implications of human actions and the transformative power of divine grace in the journey towards redemption

Canto XI – The Prayer of the Proud

First Terrace: Pride | The prideful souls recite the Lord’s Prayer, acknowledging their dependence on God. Dante meets Omberto Aldobrandeschi and Oderisi da Gubbio, who share their stories of pride and its consequences. The canto explores the theme of humility through prayer and confession.

In Canto XI, Dante and his guide Virgil find themselves on the third terrace of Purgatory, which is dedicated to the punishment of the sin of pride. This canto is pivotal as it delves into themes of humility, penance, and the consequences of pride. The canto opens with Dante reflecting on the nature of prayer and divine justice. He is in the midst of the prideful, who are burdened by heavy stones on their backs, forcing them into a posture of enforced humility. This physical burden symbolizes the weight of their earthly pride and serves as their penance.

As they proceed, Dante and Virgil encounter beautiful sculptures that serve as examples of humility, the opposite virtue to the sin being purged on this terrace. These sculptures are not described in intricate detail but are mentioned to contrast with the examples of pride carved on the pavement, which the penitents cannot see due to their bowed positions but which Dante observes.

Among the sculptures, three examples of humility are highlighted: the Virgin Mary at the Annunciation, demonstrating her submission to God’s will; King David, dancing humbly before the Ark of the Covenant; and Emperor Trajan, who, according to legend, postponed a military campaign to provide justice to a poor widow.

The canto also features a conversation between Dante and the shade of Oderisi da Gubbio, an illuminator and artist known for his pride in his work. Oderisi humbly acknowledges the fleeting nature of fame and points to the greater skill of Franco Bolognese, his contemporary, in a demonstration of humility. This encounter underlines the transient nature of earthly achievements and the importance of humility.

Oderisi discusses the concept of fame and its worthlessness in the grand scheme of eternity. He references the figures of Provenzan Salvani, a proud Sienese leader who humbled himself to free a friend from captivity, illustrating the transformative power of humble acts.

The canto concludes with Oderisi’s warning about the futility of human pride and the constant shifting of fame and fortune. He underscores the essential truth that all worldly accomplishments are overshadowed by the divine and that humility is the key to true exaltation.

This canto is rich with imagery and themes that challenge the reader to reflect on the nature of pride, the value of humility, and the impermanence of worldly glory. Through Dante’s journey and the characters he encounters, the canto offers profound insights into the path of spiritual purification and the virtues necessary for redemption.

Canto XII – The Burden of Pride

First Terrace: Pride | Dante observes more examples of pride’s consequences carved into the pavement. As he walks, the weight of the stones lifts, signifying his growing humility. An angel erases one of the P’s from Dante’s forehead, marking his progress.

Canto XII continues Dante and Virgil’s ascent through the realm of Purgatory, specifically focusing on the terrace where the sin of envy is purged. This canto is marked by vivid imagery, encounters with penitent souls, and a deeper exploration of the nature of envy and its opposing virtue, love.

As the canto begins, Dante and Virgil leave the terrace of the prideful and ascend to the second terrace, where the envious undergo their purgation. The environment here starkly contrasts with the previous terrace; the souls of the envious are clothed in coarse garments, and their eyes are sewn shut with iron wire, symbolizing the “evil eye” of envy and their inability to take pleasure in the good fortune of others. This gruesome punishment forces them to rely solely on their inner sight and contemplate their sin.

The atmosphere of this terrace is imbued with a sense of communal suffering and penitence, as the envious are compelled to listen to voices that recount examples of generosity and love, the antidotes to envy. These voices serve both as a torment to the envious, who cannot see the acts of virtue being described, and as a reminder of the love they failed to exhibit in life.

During their journey on this terrace, Dante and Virgil encounter the shade of Guido del Duca, a soul undergoing purification for the sin of envy. Guido is initially reluctant to speak but eventually engages in a conversation with Dante, lamenting the decline of noble values in Italy, particularly in the regions of Romagna and Tuscany. He mourns the loss of courtesy and virtue among the noble families of his time and criticizes the greed and envy that have corrupted society.

Guido introduces Dante to the spirit of Rinieri de’ Calboli, another penitent soul, who echoes Guido’s sentiments about the moral decay of their homeland. They discuss the impact of envy on their region, highlighting the destructive nature of this sin not only on an individual level but also on a communal and societal level.

A central theme of this canto is the destructive power of envy and the way it erodes communities and relationships. The penitents’ punishment, being blinded and forced to listen to examples of virtue, underscores the idea that envy blinds individuals to the good in others and in the world around them. The conversations with Guido del Duca and Rinieri de’ Calboli emphasize the need for love and generosity to overcome envy and restore harmony.

As the canto concludes, Dante reflects on the lessons learned from his encounters on this terrace. The stark imagery of the blinded souls and the mournful discussions about the state of Italy serve as a poignant reminder of the corrosive effects of envy and the redemptive power of love. This canto thus advances the overarching narrative of Dante’s journey through Purgatory while offering profound insights into the nature of envy and the importance of cultivating love and empathy as means of purification and redemption.

Canto XIII – The Envious Spirits

Second Terrace: Envy | On the second terrace, the envious souls have their eyes sewn shut with wire, symbolizing their inability to see the good in others. They lean on one another for support. Dante converses with Sapia of Siena, who shares her story of envy and repentance.

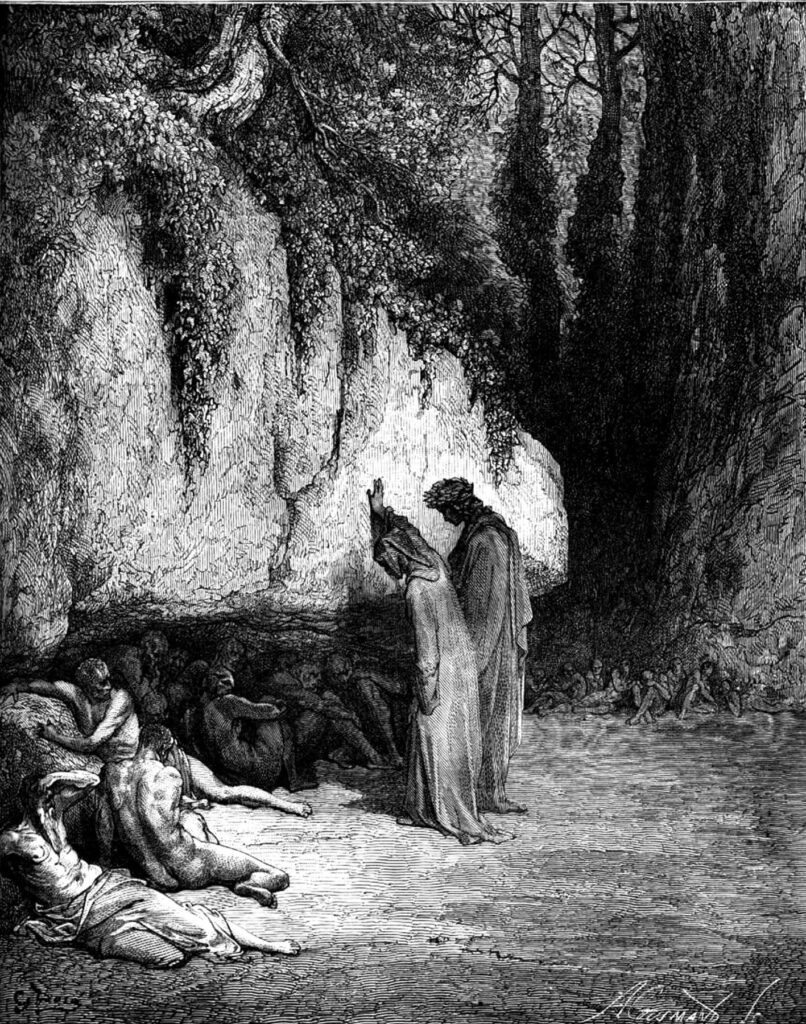

Canto XIII continues Dante’s spiritual journey through Purgatory, under the guidance of the Roman poet Virgil. This canto is situated on the fourth terrace, where the sin of envy is purged. The theme of envy is explored through the environment, the souls’ penance, and various examples of virtue and vice that serve both as a warning and an inspiration to the souls and to Dante himself.

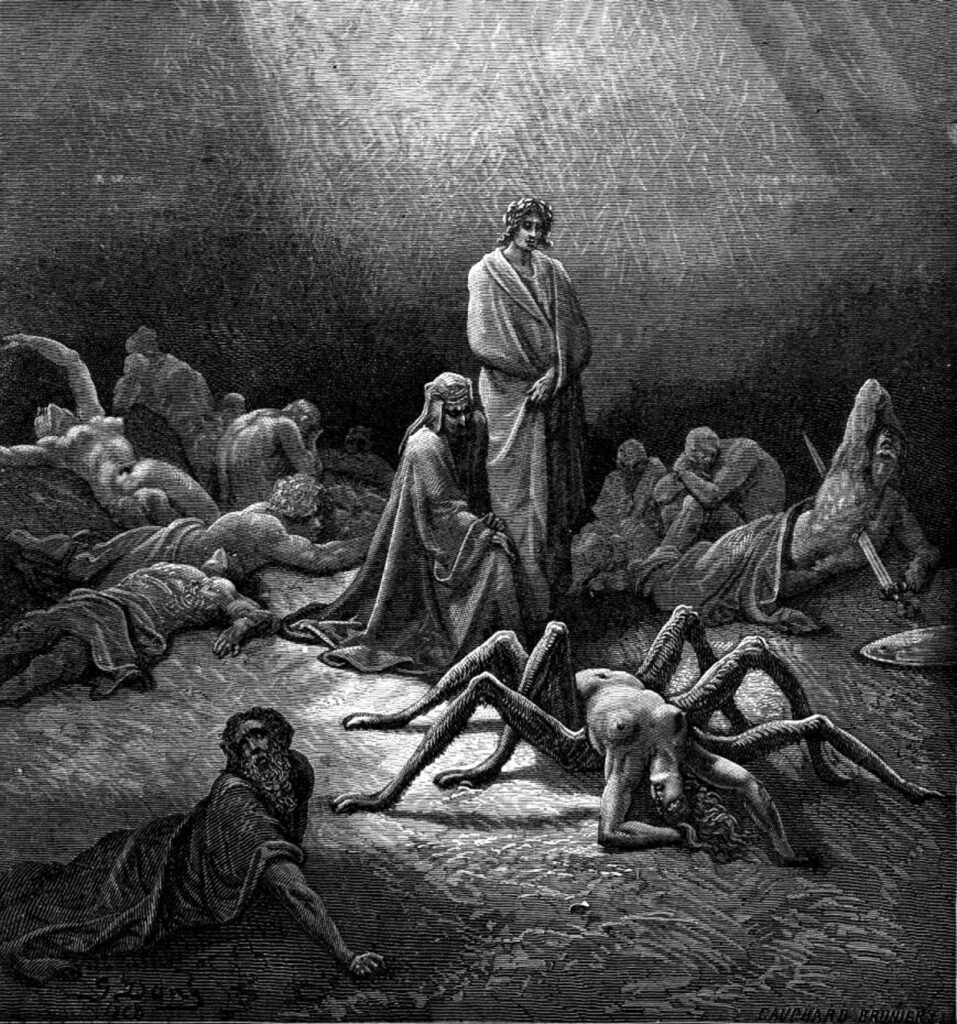

The canto opens with Dante and Virgil arriving at the terrace of the envious. Here, the environment starkly contrasts the nature of the sin being purged. The atmosphere is described as somber, with the souls clad in sackcloth, a symbol of penitence and humility. Their eyes are sewn shut with iron wire, reminiscent of the way a falcon’s hood prevents it from being distracted by external sights. This vivid and somewhat disturbing image symbolizes the blinding nature of envy and the necessity of turning inward for reflection and purification.

The souls of the envious sit along the terrace’s edge, leaning against each other for support, as they cannot see. Their inability to see is symbolic of the blinding effect of envy, which prevents individuals from seeing and appreciating the good in their own lives and in others. The penitents constantly whisper examples of virtue and vice related to envy, serving both as reminders of their sin and as motivation for their purification.

One of the central figures Dante encounters on this terrace is Sapia, a Sienese noblewoman. She shares her story with Dante, explaining how she once reveled in the misfortune of others, especially her fellow Sienese. Sapia recounts a particular event where she took perverse joy in the defeat of her own city’s army. However, she later experienced a conversion, turning to prayer and seeking intercession from Saint Francis for her soul’s salvation.

Sapia’s story serves as a cautionary tale about the destructiveness of envy but also offers hope for redemption. Her transformation from an envious individual to one seeking forgiveness underscores the possibility of change and the power of grace.

In addition to Sapia’s personal account, Dante and Virgil hear voices recounting examples of envy’s opposite virtue, charity. These include the story of the Virgin Mary’s magnificat, celebrating the joy in God’s blessings to others, and the tale of King Saul and David, where Saul’s envy led to his downfall.

So this canto concludes as a profound exploration of the nature of envy and the importance of empathy, charity, and the joy in others’ happiness. It highlights the need for self-reflection and the potential for redemption through acknowledgment of one’s sins and genuine repentance. The vivid imagery, personal stories, and contrasting examples of vice and virtue make this canto a rich and complex part of Dante’s journey through Purgatory.

Canto XIV – The Whispering Spirits

Second Terrace: Envy | The poets encounter Guido del Duca and Rinieri da Calboli, who lament the moral decline of Italy. They discuss the nature of envy and its destructive effects on society. The canto underscores the importance of communal virtue and moral integrity.

Canto XIV continues the journey of Dante and his guide Virgil through the terraces of Mount Purgatory, specifically focusing on the terrace of the envious. This terrace is the second of seven that correspond to the seven deadly sins, with each terrace serving as a place of purgation and spiritual cleansing for souls who are repentant and preparing for Paradise.

The canto opens with a prayer to the Sun, highlighting the theme of divine illumination and enlightenment, which contrasts with the blindness imposed on the envious as part of their punishment. The souls on this terrace have their eyes sewn shut with iron wire, symbolizing the blindness of their envy during their earthly lives and their inability to see the good in others. This stark image serves as a powerful representation of the self-imposed isolation and darkness that envy brings.

Dante and Virgil encounter Guido del Duca and Rinieri da Calboli, two shades who lament the moral decline of their native regions of Romagna and Tuscany. Through their conversation, Dante offers a critique of contemporary Italian politics and society, illustrating the destructive power of envy in corrupting human relationships and communities. The dialogue serves as a medium for Dante to express his concerns about the state of Italy, marked by division and moral decay.

Guido del Duca tells Dante about the nature of love and how it is perverted into envy. He explains that love, which should direct people towards virtuous actions and the desire for others’ good, can become twisted and lead to resentment of others’ happiness. This perversion of love underlies the sin of envy and is central to the punishment and purgation of the souls on this terrace.

The canto also delves into the concept of noble heritage and the misuse of ancestral reputations. Guido laments how contemporary nobles rest on their laurels, relying on their ancestors’ deeds while neglecting to cultivate their own virtues. This critique extends Dante’s exploration of envy to include the envy of past glories and the failure to contribute positively to one’s legacy.

As the canto progresses, a voice from among the envious souls recites examples of generosity and love—the opposites of envy. These include the Virgin Mary’s Magnificat, the classical figure of Pygmalion, and the Roman general Fabricius. These examples serve as reminders of the virtues that the envious should have practiced, emphasizing the transformative power of love and generosity over the corrosiveness of envy.

Canto XIV ends with Dante and Virgil preparing to leave the terrace of the envious. The canto’s themes of moral decline, the perverted nature of love, and the critique of contemporary society are woven together to underscore the poem’s broader exploration of sin, repentance, and redemption. Through the vivid portrayal of the envious and their interactions with Dante, the canto offers profound insights into the nature of envy and the path toward spiritual purification.

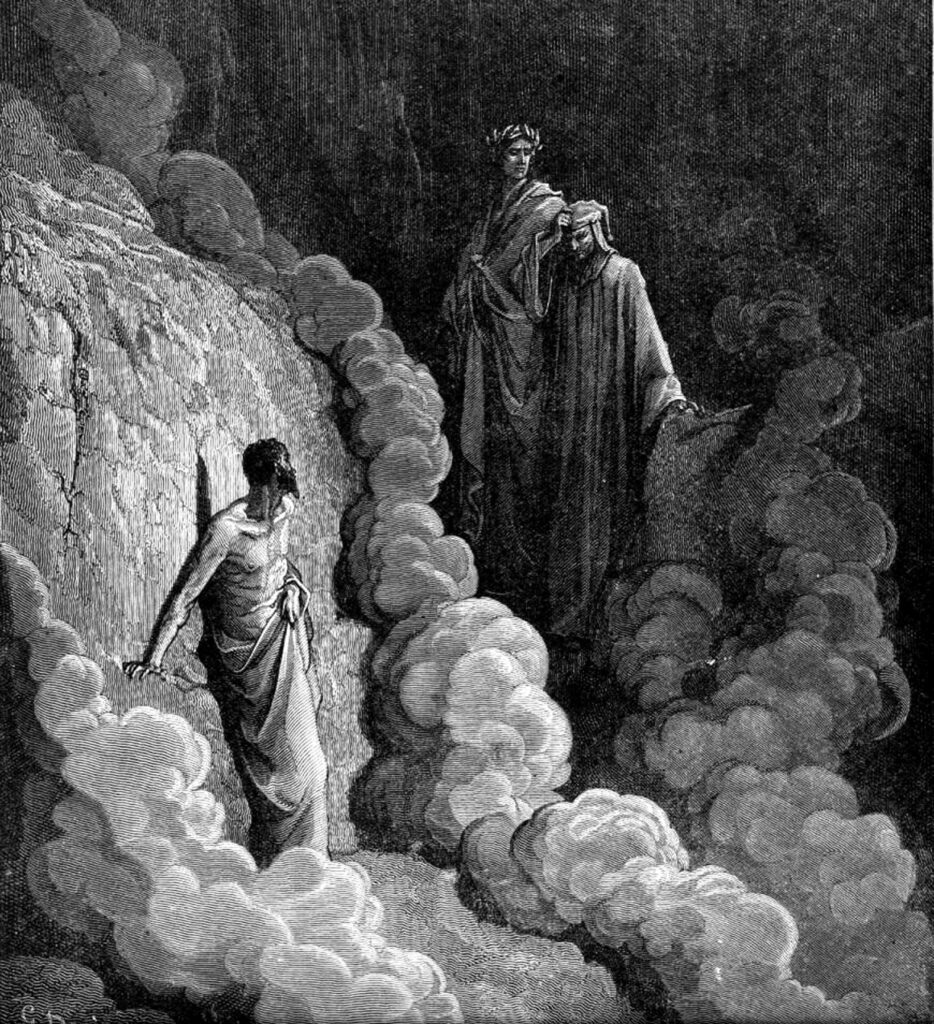

Canto XV – The Vision of Charity

Third Terrace: Wrath | Dante is enveloped in a bright light and hears a voice extolling the virtue of charity. The poets reach the third terrace, where the wrathful are surrounded by a thick smoke. The canto reflects on the purifying power of love and the destructive nature of wrath.

Canto XV marks a transition from the terrace of the envious to the third terrace, where the wrathful undergo their purgation. This canto is particularly notable for the encounter between Dante and his old friend Marco Lombardo, through which Dante explores themes of free will, the nature of sin, and the impact of human choices on the world.

As the canto opens, Dante and his guide Virgil have just left the terrace of the envious and are enveloped in a dense, acrid smoke, representing the blinding nature of anger. This smoke serves both as a literal obstacle to vision and as a metaphor for the way anger obscures one’s rational judgment and understanding.

Within this obscurity, Dante encounters the spirit of Marco Lombardo, who recognizes Dante despite the enveloping smoke, indicating a perception that transcends physical sight—a common motif in Purgatory, where spiritual insight often surpasses the limitations of the senses. The meeting is cordial, and Marco expresses his willingness to help Dante in his quest for understanding.

A significant portion of their conversation focuses on the concept of free will, which Marco asserts is a God-given gift to humanity, distinguishing humans from other creatures. He argues that despite the corrupting influences of the stars (astrological determinism) and societal structures, humans possess the innate ability to choose between good and evil. This capacity for moral choice underscores the poem’s broader theological and philosophical exploration of human responsibility and the potential for redemption.

Marco then laments the state of Italy and the world, attributing the moral decay to the failure of its leaders to exercise their free will virtuously. He criticizes the church’s involvement in temporal affairs, suggesting that this has led to a neglect of spiritual leadership and a consequent decline in social morality. This critique reflects Dante’s own concerns about the political and spiritual crises of his time, particularly the conflict between the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire.

The discussion between Dante and Marco Lombardo delves deeper into the causes of sin and the nature of divine justice. Marco explains that while the heavens may influence human dispositions, they do not determine human actions; thus, individuals must take responsibility for their choices. He emphasizes the importance of proper education and guidance in shaping the will towards goodness, highlighting the role of earthly authorities in maintaining moral order.

As the canto concludes, Marco directs Dante and Virgil towards the ascent to the next terrace. The encounter with Marco Lombardo serves as a poignant reflection on the power and significance of free will in the journey of the soul towards purification and redemption. Through this dialogue, Dante articulates a vision of human potential that is both challenging and hopeful, grounded in the belief in the individual’s capacity to overcome sin through conscious moral effort.

Canto XV stands out for its philosophical depth, engaging with complex theological issues while also offering a critique of contemporary society. Through the character of Marco Lombardo, Dante presents a nuanced understanding of sin, free will, and the potential for human virtue, making this canto a key part of the spiritual and intellectual journey depicted in “Purgatorio.”

Canto XVI – The Wrathful Souls

Third Terrace: Wrath | In the smoky third terrace, Marco Lombardo explains the relationship between free will and divine justice. He criticizes the corruption of the Church and state, emphasizing the need for moral responsibility. The canto explores the complexities of human freedom and moral accountability.

Canto XVI continues Dante’s journey through the terrace of the wrathful, where souls are purified of the sin of wrath. This canto delves deeply into the themes of divine justice, repentance, and the nature of wrath as both a personal and group sin.

The canto begins with Dante and his guide, Virgil, still enveloped in the dense, acrid smoke that symbolizes the blinding nature of anger. This smoke, which obscures physical vision, serves as a metaphor for how wrath can cloud one’s judgment and moral clarity, reinforcing the idea that the punishment in Purgatory mirrors the nature of the sin being purged.

Emerging from the smoke, Dante encounters three spirits: Marco Lombardo, whom he met in the previous canto, and two new souls, Guido Guinizelli and Guido Cavalcanti. Guinizelli, a poet whom Dante admires, represents the idea that even those with great talents and virtues can fall prey to wrath. Cavalcanti, also a poet and a close friend of Dante’s, underscores the poem’s theme of personal connections and the impact of sin on relationships.

The spirits engage Dante in a conversation about the nature of love and wrath. They discuss how love, when misdirected or excessive, can lead to wrathful actions, highlighting the fine line between righteous indignation and destructive anger. This conversation reflects the medieval understanding of sin as a perversion of natural inclinations, with wrath seen as a distortion of the natural human impulse to react against perceived wrongs.

As the dialogue unfolds, the spirits ask Dante to carry news of their condition back to the world of the living. This request underscores the communicative function of Dante’s journey, as he serves as a link between the living and the dead, and his poem becomes a medium for the voices of the souls in Purgatory.

The encounter with the souls of the wrathful also serves as an occasion for Dante to reflect on his own tendencies toward anger, prompting a moment of introspection and self-awareness. This personal dimension adds depth to the canto’s exploration of wrath, making it not just a theoretical discussion but also a deeply human one.

A significant aspect of Canto XVI is its emphasis on the role of penance and divine justice in the process of purification. The souls in Purgatory willingly submit to their punishments, recognizing them as necessary steps towards redemption. This willingness reflects the poem’s broader theological vision of Purgatory as a space of healing and growth, where the pain of punishment is ultimately transformative.

The canto concludes with a further ascent up the mountain of Purgatory, signaling the pilgrim’s progress both in his physical journey and in his spiritual understanding. The interactions with the souls on the terrace of the wrathful deepen Dante’s comprehension of sin and redemption, preparing him for the challenges and revelations that lie ahead.

Canto XVI, with its focus on wrath, love, and the possibility of redemption, captures the complex interplay between human emotions, moral choices, and divine justice. Through Dante’s encounters and conversations with the souls of the wrathful, the canto offers profound insights into the nature of sin and the path toward purification and peace.

Canto XVII – The Night in Purgatory

Third and Fourth Terrace: Wrath & Sloth | Virgil discusses the nature of love and its role in motivating human actions. The poets prepare to leave the terrace of the wrathful as an angel guides them upwards. The canto delves into the philosophical underpinnings of love as a force for both good and evil.

Canto XVII unfolds on the third terrace of Purgatory, where souls who succumbed to the sin of wrath are being purified. This canto is pivotal as it delves into the themes of anger’s nature, the process of purgation, and the importance of forgiveness and patience.

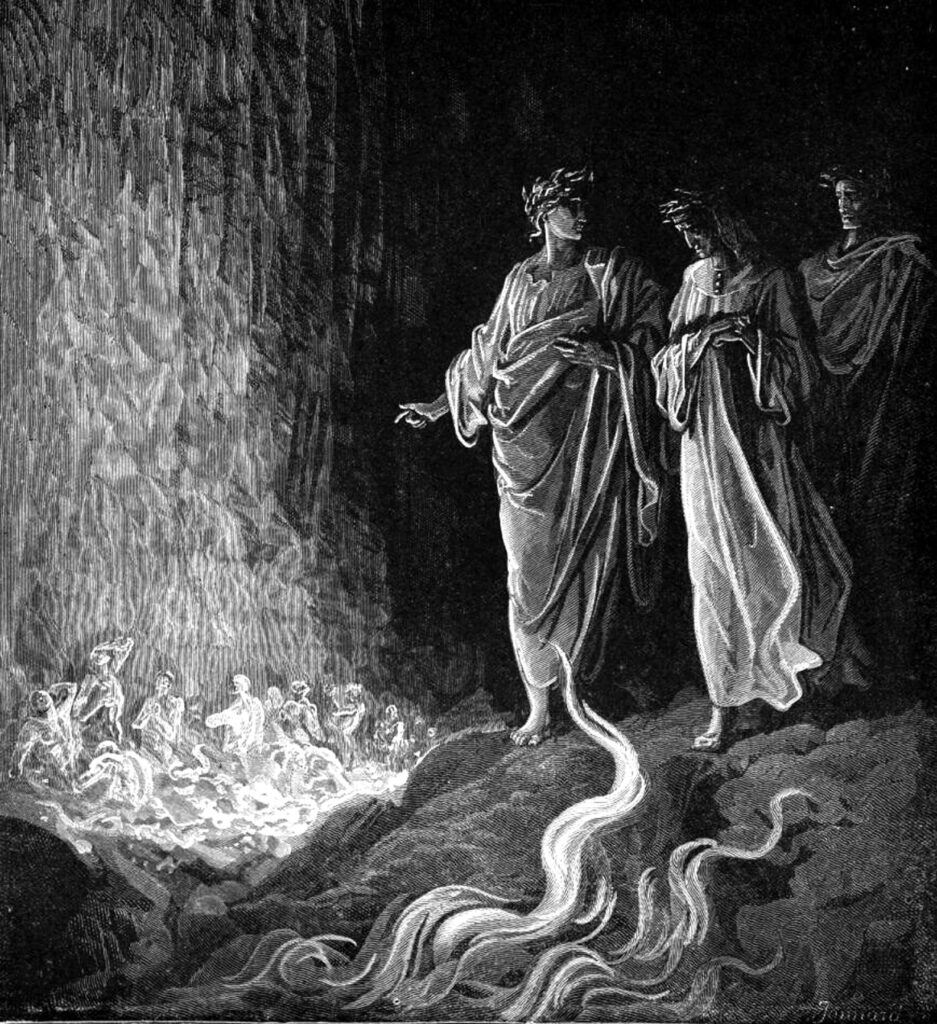

The canto begins with Dante and Virgil still enveloped in the dense, acrid smoke that symbolizes the blinding effect of anger on human judgment and perception. As they emerge from this obscurity, indicative of the souls’ emerging clarity as they are purged of wrath, they encounter an angel who represents the virtue of meekness, the antidote to wrath. The angel wipes a P (one of the seven Ps representing peccata, or sins, inscribed on Dante’s forehead at the base of Purgatory) from Dante’s brow, signifying the partial purification of his soul from the stain of wrath.

As they proceed, Dante is curious about the principles of divine justice and the allocation of souls in the afterlife. He inquires of Virgil how it’s determined whether a soul ascends to Heaven immediately after death, lingers in Purgatory, or descends into Hell. This inquiry introduces one of the central theological themes of the canto—the justice of divine judgment and the role of repentance at the moment of death.

Virgil explains that God’s justice is inscrutable and operates beyond the bounds of human understanding. However, he elucidates that the contrition, or heartfelt repentance, and the love of good, which is the contrary to the sin committed, can expedite a soul’s journey to salvation, even in the final moments of earthly life. He highlights the importance of genuine repentance, which must be pure and devoid of any wish to sin again, coupled with the soul’s longing for God.

The canto introduces the concept of “the last of life,” referring to the critical moment just before death when the soul’s fate is sealed. Virgil clarifies that if repentance is genuine and if the soul calls out to God with true love and contrition, it can still be saved, even if it lacked the opportunity to demonstrate this change through deeds. This highlights the compassionate aspect of divine justice, emphasizing mercy and the power of genuine repentance.

A soul overhearing Dante and Virgil’s conversation interjects, seeking news of the earthly realm. This soul, later revealed as Statius, an ancient Roman poet, has been purged of wrath and is nearing the end of his purgatorial journey. His presence emphasizes the transformative power of purgatory, where souls learn from their sins and grow towards divine love.

Statius explains his own journey, revealing that he was inspired to convert to Christianity by Virgil’s own works, which he interprets as prophetic of the coming of Christ. This moment highlights the intertextual nature of “The Divine Comedy,” where Dante weaves his narrative with threads from classical antiquity, Christianity, and medieval thought, blending them into a cohesive theological and poetic vision.

Canto XVII thus serves as a narrative bridge, concluding the purification from wrath and setting the stage for the exploration of sloth, the next sin to be purged. Through dialogues on divine justice, the nature of repentance, and the interactions between Dante, Virgil, and Statius, the canto explores deep theological questions while advancing the pilgrims’ journey towards spiritual enlightenment.

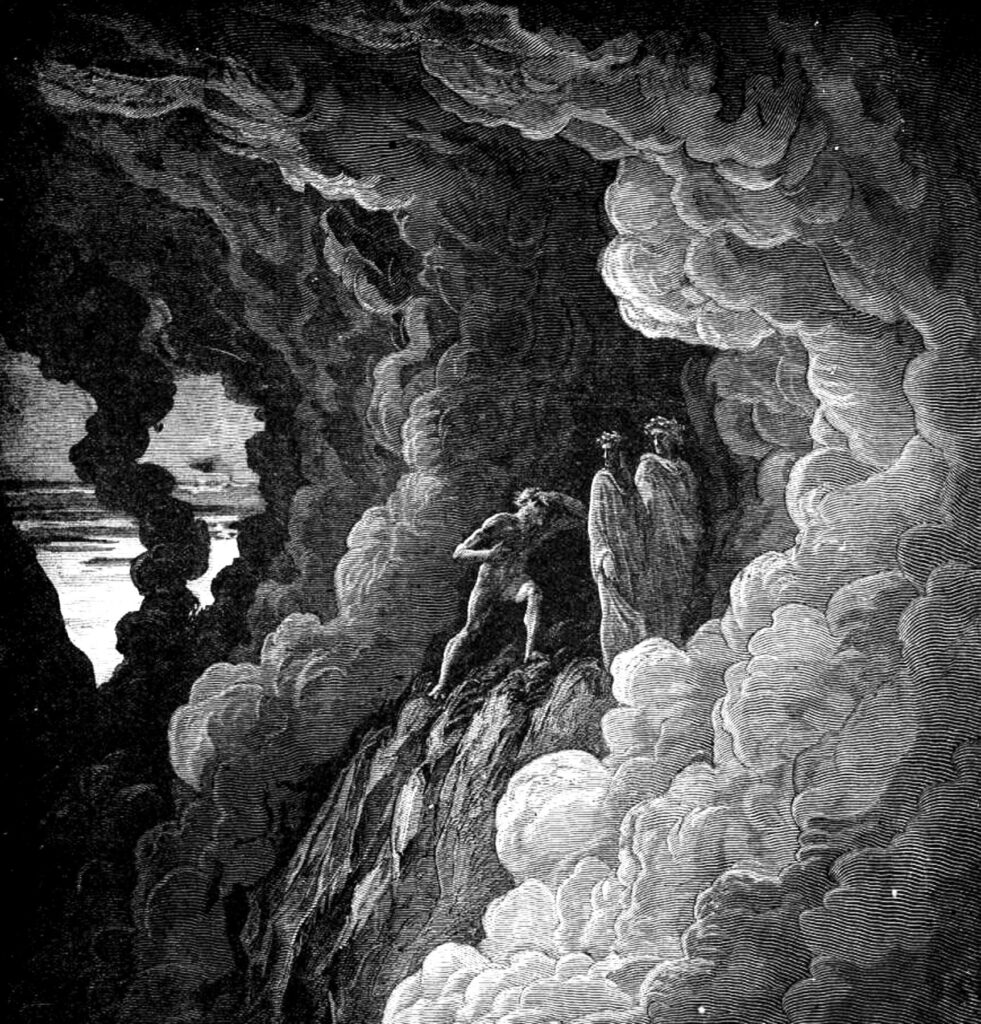

Canto XVIII – The Slothful Souls

Fourth Terrace: Sloth | The poets encounter the slothful, who constantly run to purge their laziness. Virgil elaborates on the concept of love, distinguishing between natural and rational love. The canto emphasizes the importance of zeal and the dangers of spiritual lethargy.

Canto XVIII is significant for several reasons, primarily because it marks the transition between the third and fourth terraces of Purgatory, where the sins of wrath and sloth are purged, respectively. This canto, rich in theological and philosophical discussion, continues the conversation between Dante, his guide Virgil, and the newly introduced character Statius, a Roman poet who has been purified of his sins in Purgatory.

The canto opens with the continuation of the conversation between Virgil and Statius. Statius, having been purged of his sin of prodigality, explains how he came to convert to Christianity, inspired partly by Virgil’s own works, which he interpreted as having Christian prophetic elements, particularly the Fourth Eclogue. This moment highlights the profound influence of Virgil’s poetry, not only on Dante but also within the fictional universe of “The Divine Comedy.” Statius’s reverence for Virgil also serves as a testament to the enduring legacy of classical literature and its capacity to convey eternal truths.

As they converse, the poets are on the move, transitioning from the terrace of the wrathful to that of the slothful. This movement is marked by a change in the environment around them. The heavy, acrid smoke that blinded and choked them as a manifestation of anger gives way to clearer air, signifying their passage to a new stage of purification.

The theme of sloth is introduced through a discussion of love, which, according to Statius, is the driving force behind all actions. He delineates two types of love: natural love, which is always directed towards good and cannot err, and elective love, which can be misdirected if not guided by virtue. Sloth, in this context, is described as a failure to love good with the intensity and zeal it deserves. This discussion provides a deeper understanding of the nature of sin in Dante’s conception, where sin arises not from love itself but from the misdirection or deficiency of love.

As they ascend to the fourth terrace, they encounter the souls of the slothful, who are now purged of their sin and are running around the terrace with unceasing zeal, chanting examples of zeal and sloth from Scripture and history. This vigorous activity contrasts sharply with their previous sin of sloth, emphasizing the transformative power of penance in Purgatory. The examples they chant serve as both penance for their sin and instruction for Dante and the readers, illustrating the virtues they failed to practice in life.

One of the notable features of this canto is the interaction between the three poets, which showcases Dante’s deep respect for classical literature and its authors. The relationship between Dante, Virgil, and Statius is one of mutual admiration and learning, highlighting the continuity between classical antiquity and Christian thought.

Canto XVIII thus serves as a pivotal moment where the themes of love, sin, and redemption are explored through the conversations between Dante, Virgil, and Statius. The transition between the terraces of wrath and sloth provides a narrative and thematic bridge, deepening the reader’s understanding of the structure of Purgatory and the process of spiritual purification that takes place within it. Through these interactions and the depiction of the souls on the fourth terrace, Dante continues to weave a complex tapestry of moral and theological lessons, grounded in Christian doctrine and enriched by classical antiquity.

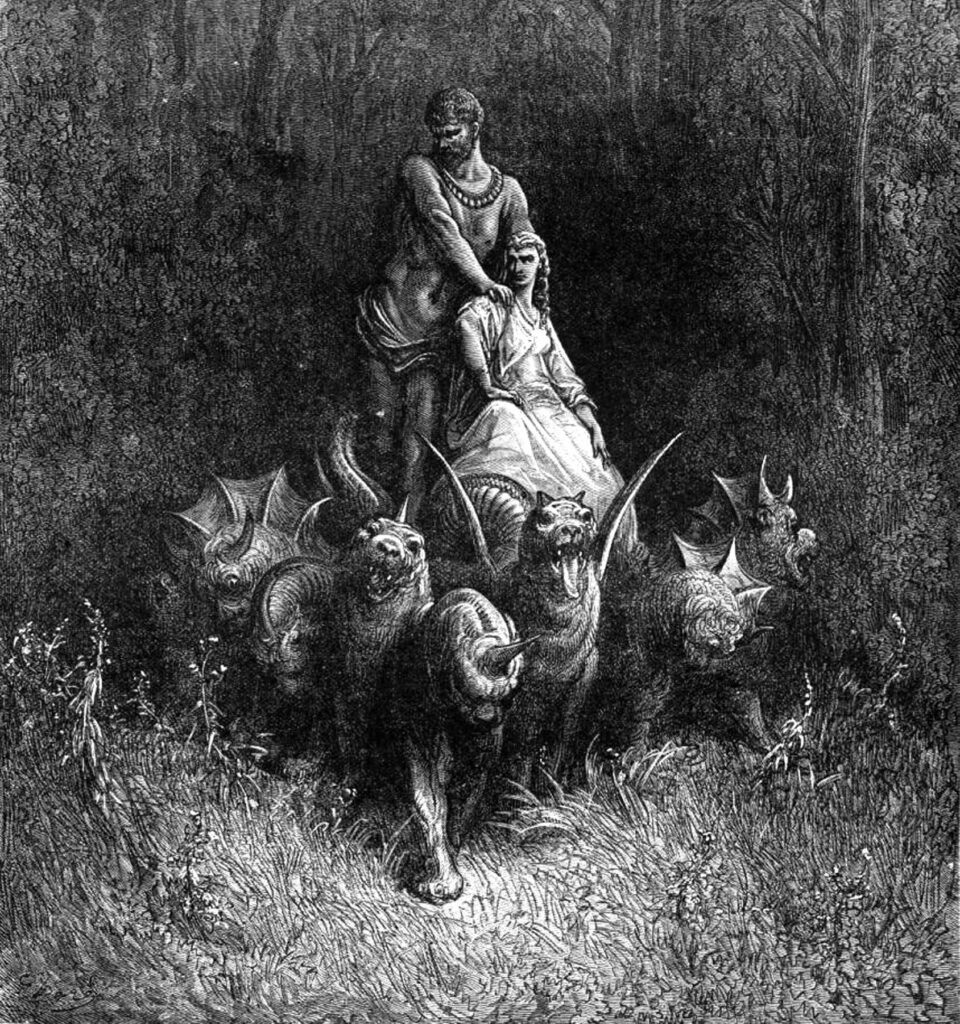

Canto XIX – The Dream of the Siren

Fifth Terrace: Avarice and Prodigality | Dante dreams of a siren representing false pleasures. Upon awakening, the poets reach the fourth terrace, where the avaricious and prodigal lie face down, weeping. The canto explores the seductive power of material wealth and the necessity of spiritual detachment.

Canto XIX continues Dante’s spiritual journey up the terraces of Mount Purgatory, focusing on the fourth terrace, where the sin of sloth (acedia) is purged. This canto delves into themes of zeal, spiritual apathy, and the consequences of not acting upon good intentions.

The canto begins with Dante’s scornful address to the Simoniacs, who have turned a sacred office into a marketplace. He compares them to Simon Magus, a figure from the New Testament who tried to buy the power of the Holy Spirit from the apostles, a story from which the term “simony” derives.

Dante and Virgil see the sinners buried headfirst in rock with their feet sticking out, ablaze with flames. This punishment is a gruesome, ironic inversion of the sacrament of baptism, which symbolizes spiritual rebirth through immersion in water. Instead, these sinners are buried in earth, with the flames symbolizing not the Holy Spirit, but the divine wrath they have earned.

The two travelers come across Pope Nicholas III, who mistakes Dante for his successor, Pope Boniface VIII. Dante uses this opportunity to critique the corruption in the Church, as both popes were accused of simony during their papacies. Nicholas laments his fate and predicts the arrival of Boniface, stating that he too will soon endure the same punishment. He also foretells the coming of a third simoniac pope, Clement V.

During his conversation with Nicholas, Dante voices his disgust at the way the Church’s spiritual authority has been exploited for personal gain, calling it a perversion of its intended purpose. He views this corruption as not just sinful but also as a betrayal of the faith.

When Nicholas finishes his predictions, he returns to his punishment, and Virgil lifts Dante to descend to the fifth pouch. Before they leave, Dante delivers a passionate critique of the corruption and greed that have infected the Church.

Canto XIX is a particularly poignant part of Dante’s journey through Hell as it emphasizes the poet’s fury at the corruption within the Church. His use of real historical figures cements the reality of the sins committed and provides a powerful critique of the individuals involved and the institutions that allowed such transgressions.

Canto XX – The Avaricious and Prodigal

Fifth Terrace: Avarice and Prodigality | The poets encounter Hugh Capet, who criticizes the greed of his descendants. Dante witnesses the souls of the avaricious lamenting their sins. The canto critiques the corrupting influence of greed on both individuals and dynasties.

Canto XX is set on the fifth terrace of Purgatory, where the sin of avarice is purged. This terrace is dedicated to cleansing the souls of those who either hoarded or squandered earthly wealth, embodying the two opposite but related forms of the sin of greed.

The canto opens with Dante and his guides, Virgil and Statius, arriving on the terrace to find the souls of the avaricious and the prodigal lying face down on the ground. This posture symbolizes their attachment to earthly possessions in life and serves as a form of penance, forcing them to focus away from the material world they once excessively valued. The weight of their sin is made literal as they are immobilized, pressed down by the force of divine justice, illustrating the heavy burden that greed and materialism place on the soul.

As Dante observes these souls, he hears their lamentations and prayers, particularly the repeated chant of Psalm 119:25 (“Adhaesit pavimento anima mea,” or “My soul cleaveth unto the dust”), which reflects their acknowledgement of how their souls clung to the earthly wealth, like dust, and their desire for spiritual upliftment.

Among these souls, Dante encounters Pope Adrian V, who, in a humbling reversal of his former papal authority, now lies prostrate among the other penitents. Adrian’s inclusion highlights the theme that high religious office does not exempt one from the consequences of sin, and in death, all souls are equal before divine justice. Adrian’s humility in acknowledging his sin and his focus on the spiritual over the temporal power he once wielded serve as a powerful example of repentance and transformation.

Pope Adrian V shares with Dante his realization of the vanity of earthly power and wealth, which came too late to prevent his damnation to Purgatory. He emphasizes the fleeting nature of life and the importance of focusing on eternal salvation over temporal gains. This encounter underscores the central message of the canto: the need to detach from material possessions and to seek spiritual wealth.

Adrian also requests Dante to inform his niece, Alagia, of his fate, suggesting a continued concern for the living and the potential for the living to pray for the souls in Purgatory, aiding their purification process. This interaction underscores the interconnectedness of the living and the dead within the medieval Christian worldview and the communal aspect of salvation.

The canto concludes with a discussion between Dante and Virgil about the nature of the souls’ prayers and their focus on earthly concerns. Virgil explains that even though the souls pray for material outcomes, their prayers are ultimately directed toward the alignment of their wills with God’s divine will, which transcends earthly matters.

Finally, this canto delves deeply into the sin of avarice, exploring its manifestations and consequences through the vivid depiction of the penitents’ sufferings and their prayers for redemption. The encounter with Pope Adrian V serves as a poignant reminder of the transitory nature of earthly life and the ultimate importance of spiritual values. Through this canto, Dante continues to weave his complex theological and moral vision, emphasizing the themes of repentance, humility, and the reorientation of love and desire toward the divine.

Canto XXI – The Arrival of Statius

Fifth Terrace: Avarice and Prodigality | Dante and Virgil meet the soul of Statius, who explains his conversion to Christianity and expresses gratitude to Virgil’s writings. Statius accompanies them on their journey. The canto highlights the transformative power of literature and the interplay between pagan and Christian traditions.

Canto XXI unfolds on the sixth terrace of Purgatory, where the sin of gluttony is purged. This canto is rich in allegory and symbolism, offering profound insights into human desires, the nature of temperance, and the process of spiritual purification.

As Dante and his guides, Virgil and the Roman poet Statius, arrive on this new terrace, the environment immediately reflects the nature of the sin being expiated here. The souls of the gluttonous are emaciated, a stark contrast to their indulgence in food and drink during their earthly lives. This physical transformation serves as both a penance for their sin and a visible sign of their inner spiritual state.

The canto begins with a vibrant depiction of the natural beauty of the terrace, which is adorned with fruit trees. Despite the lushness around them, the souls cannot partake of the fruits, which remain tantalizingly out of reach. This setup is a poignant representation of the virtue of temperance, as the souls learn to control their desires through the very deprivation that once fueled their sin.

A notable encounter in this canto is with the shade of Statius, who reveals that he has spent five hundred years in Purgatory, purging the sin of gluttony among others. His presence alongside Dante and Virgil continues to add depth to the narrative, bridging the classical and Christian worlds and illustrating the transformative power of divine grace.

The canto also introduces an angelic figure who guards the passage to the next terrace. The angel is described with ethereal beauty and emits a light so bright that Dante cannot look directly at it, symbolizing the purity and holiness that the souls aspire to through their penance. The angel’s presence reinforces the canto’s themes of divine guidance and the promise of redemption for the repentant souls.

One of the most visually striking and symbolic moments in Canto XXI is the appearance of a mysterious procession that includes an elaborate chariot and figures that represent various biblical and theological virtues and concepts. This procession is rich in allegorical meaning, reflecting the complex interplay of human history, divine providence, and the soul’s journey towards salvation.

The encounter with the angel and the procession underscores the canto’s exploration of sensory experiences and desires. The angel’s blinding light contrasts with the darkness that often symbolizes sin and ignorance, while the unreachable fruits and the ethereal music of the procession highlight the theme of temperance and the reorientation of desire towards the divine.

Canto XXI thus serves as a profound meditation on the nature of gluttony and the virtue of temperance, using vivid imagery and allegory to explore the themes of desire, deprivation, and spiritual growth. Through the experiences of the penitent souls and the symbolic elements of the terrace, Dante offers insights into the process of purgation and the reorientation of the soul’s desires away from earthly pleasures and towards the eternal love of God. The canto reinforces the overarching narrative of “Purgatorio” as a journey of transformation, where the purging of sin and the cultivation of virtue prepare the souls for their eventual ascent to Paradise.

Canto XXII – The Reunion of Poets

Fifth Terrace: Avarice and Prodigality | Statius discusses his admiration for Virgil and recounts his own purification process. The poets reach the fifth terrace, where the gluttonous suffer from insatiable hunger and thirst. The canto emphasizes the importance of temperance and the dangers of excess.

Canto XXII continues to explore the theme of avarice but with a focus on the communal aspect of repentance and the intercession of prayers for the souls in Purgatory. This canto is particularly rich in its portrayal of the dynamics of prayer, penance, and the interconnectedness of all souls within the Christian cosmology.

As the canto begins, Dante and his guides, Virgil and the Roman poet Statius, are still on the fifth terrace of Purgatory, where the souls of the avaricious and prodigal are being purified. These souls, who in life were excessively attached to material wealth, now lie face down on the ground as a form of penance, symbolizing their detachment from earthly possessions.

The narrative is advanced by the arrival of an angel who guides Dante and his companions to the next terrace. This angelic encounter is a recurring motif in Purgatory, signifying Dante’s progress in his spiritual journey. Each angelic visitation is accompanied by the erasure of a P (for peccatum, meaning “sin”) from Dante’s forehead, indicating the purging of a particular sin. The angel also imparts a beatitude, in this case, “Blessed are the peacemakers,” which contrasts with the discord sown by greed and avarice.

The transition between terraces is marked by a change in the environment. The poets ascend a natural staircase, which symbolizes the gradual and arduous nature of spiritual purification. As they climb, Statius explains the process of soul purification in Purgatory, shedding light on the theological underpinnings of the afterlife as imagined by Dante. This discussion deepens the reader’s understanding of the journey’s spiritual significance and the mechanics of redemption.

Upon reaching the sixth terrace, where the sin of gluttony is purged, the narrative shifts to focus on the nature of this sin and its penance. The souls here are emaciated, reflecting their excessive indulgence in food and drink in their earthly lives. The sensory deprivation they experience, being surrounded by the aroma of fruit and the sound of water they cannot consume, serves as their penance. This ironic punishment forces them to confront their sin directly, emphasizing the theme of temperance and the need to find a balance between deprivation and excess.

Dante encounters Forese Donati, a friend from his past, among the souls being purged of gluttony. Their exchange highlights the transformative power of prayer and penance. Forese attributes his relatively swift progress through Purgatory to the fervent prayers of his pious wife, Nella, demonstrating the impact of the living’s prayers on the souls of the deceased. This encounter reinforces the communal aspect of salvation and the role of the living in aiding the souls in Purgatory.

Forese also provides Dante with information about the current state of Florence, lamenting the moral decay of the city. This reflection on contemporary social issues serves as a critique of the temporal concerns that distract from spiritual well-being, tying back to the central themes of the canto and the terrace.