The following are chapter notes in the form of questions and answers that cover the subject matter of the book, “To Know and Love God.” The book is a monograph from David Clark and it is about the theological methodology of evangelicalism. It was published in 2003 by Crossway Books (Good News Publishers, Wheaton Illinois).

Chapter One: Concepts of Theology

1. What was the historical task of the church as it relates to theology?

Justin Martyr (c. 100–c. 164) sought to articulate the content of the gospel of Jesus Christ to the context of a particular culture. Historically, this was the task of systematic theology (Clark, 33). That is, to relate to others the gospel and the meaning of faith in Christ.

2. Does philosophy and reason have a relationship with theology?

Philosophy and human reason are subordinate to theology. Philosophy is merely a tool to demonstrate the fundamental truths of theology. Theology goes beyond the bounds of philosophy (Clark, 38). Human reason is the lesser of all faculties of understanding due to its limitations and the presence of sin. Aquinas’ (1225–1274) view was that faith and reason reinforced theology as some doctrines were out of reach by reason alone. Reason and faith provided the means to observe, set categories, conclude, and trust by acceptance revealed truth.

3. What were the differences in theology between Schleiermacher and Barth?

Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834) rooted theology in religious experience (Clark, 43). He was the father of liberal theology, who formed a new model of theology around people’s religious experience. He cut God off as the object of theology to emphasize what humanity experienced about Him.

Karl Barth (1886–1968) viewed theology as dogmatics entirely independent of human modes of thought. He viewed theology as the science of dogma.

4. What were conservative theologians concerned about by reasoning during the modern era.

Martin Luther (1483–1546) viewed the subject of theology as man, guilty of sin and condemned, while God is the redeemer of mankind as sinners (Clark, 40) and “Whatever is asked or discussed in theology outside this subject, is error and poison.” Like Luther, John Calvin (1509–1564) held a biblical orientation toward theology and theistic metaphysics. Luther and Calvin distrusted human reason and saw the purpose of theology as salvation.

Through the Word, the Holy Spirit reveals theological truth to those who seek God to glorify Him and follow His instructions to include the spread of the gospel, holy living, and the search for wisdom, among other pursuits. Luther and Calvin, in this sense, had an undeveloped utilitarian view of theology as there are numerous doctrines formed by revelation through the Holy Spirit by the patriarchs, apostles, and prophets (i.e., scripture).

5. What is meant by contextual and kerygmatic poles of theology?

The poles are polarities in which liberal and conservative ideas of narrative thought are either synergistic through liberal reason and human experience or strictly authoritarian by the Word-centered standards of theological and gospel truth that exist from inspired scripture (Clark, 52). The gospel message supported by theology must be given and made relevant to all peoples along the liberal, moderate, and conservative spectrum. At each polarity, or both poles. The gospel is made clear and not necessarily in strict adherence to all doctrines as a matter of theological truth and coherence.

Chapter Two: Scripture and the Principle of Authority

1. What is moral and veracious authority? What is the difference between them?

They’re both forms of authoritarianism. One concerns truth (veracious authority), and the other concerns morality (moral authority).

Veracious authority refers to communicative truth to a viewer or listener from a communicator. Because of who the communicator is, the recipient is justified or rational to accept a message as true or valid.

Moral authority refers to an asserted position or status in leadership that opposes and fights moral evil and therefore exerts power or the capacity to apply it.

2. Describe ontological ground of biblical authority and epistemic acceptance.

The ontological ground of theology originates from God, who we know, and not from us who do the knowing (Clark, 182). Imbued knowing comes from objective reality by grace and revealed truth by the Spirit’s inspiration from scripture (Clark, 65). God is the authority by which acceptance of what He reveals is made certain upon epistemic and ontological grounds.

3. What is intentional fallacy?

The intentional fallacy is the false belief that a reader can get into the author’s mind to reveal private mental acts aside from what was written. The inference of written text doesn’t correlate to what is in the mind of the author. Unexpressed inwards thoughts of an author don’t correspond to meaning inaccessible to a reader (Clark, 70).

The illocutionary force of what the Spirit conveys through biblical authors gives meaning to what is authoritative, accepted, and actionable. The witness of the Holy Spirit to the meaning and force of scripture is what gives it authority as God’s Word (Clark, 83).

4. What objections can be put up against the appeal to authority?

First, “a commitment to theological authority usually deteriorates into authoritarianism” (Clark, 75). This objection is not valid because Scripture itself subverts religious authoritarianism (Clark, 77). Second, some argue a circularity in theological methodology and it cannot provide warrant for its assertions (Clark, 79). This objection is invalid because warrant is found in the affirmation of the life of the Church, the self-witness of the Holy Spirit, and sola scriptura. Objections to the appeal to authority are not subjugated to the critical method because its assertions and evidence are not defeated by outside claims against reliable biblical witnesses (Clark, 80).

5. Do theological propositions have value beyond the text of Scripture?

We are to use the Bible for spiritual formation and worship. However, it is of value to appreciate theological propositions from among those who place themselves under biblical authority (Clark, 236). Not necessarily to accept or adopt those propositions, but to appreciate them for purposes of research or discovery. Such sources, such as early documents, sayings, or the pseudepigrapha, must not keep us from the Bible itself (Clark, 96). This is of utmost necessity because the Bible itself is authoritative.

Chapter Three: Theology in Cultural Context

1. To what extent is current evangelical theology contextualized?

Poverty relief, language and traditions, biblical instruction within the framework of national heritage, and limited tolerance of worldview are examples of how theological principles are conveyed and transferred to people groups of various interests and backgrounds. Specifically, a contextualized theology produces doctrines of orthodoxy and orthopraxy. Together, they integrate in a relevant, tolerant, and supportive way toward Kingdom interests and the gospel. Across ethnicities, races, generations, cultures, and time.

2. In what way is contextualized theology a positive thing?

Contextualized theology is included within the imperative to make disciples of all nations. It’s scriptural theology to infer biblical and kingdom principles as they become situated within existing conditions of different well-established contexts. Such as language, customs, traditions, resources, social environments, and values as people become transformed as citizens of yet another Kingdom.

Occupants of where they dwell or reside physically, but they undergo a worldview transformation toward a new and growing Kingdom. From revelation, it’s a resolute perspective (I’m aware of the dangers of perspectivalism, Clark ch.4) that prevails to accept core doctrines and biblical or theological principles that by necessity unify in truth. Every bit of it framed in a cultural context absent hostilities by ideology and ”social justice” endeavors that would seek to destroy the family, the church, and Western civilization. Particularly in support of objectives around attempts to force acceptance of gender identities, sexual orientation, feminism, and Islamic Jihad (i.e., Sharia law) as a matter of evil self-interest. Tolerance is one thing, but acceptance and support of those objectives are quite another.

3. How should this contextualization be accomplished if it is an appropriate goal?

A transcultural approach toward contextualized theology can be appropriate depending upon the target culture. As necessary to bring the gospel and discipleship to the nations and their cultures, our obligation to fulfill Christ’s imperatives becomes satisfied. As appropriately suitable, according to biblical standards, existing cultures must not be reshaped or lost, provided they’re within biblically specified forms of new covenant ethics and morality.

By successive approximation and iteration, harmful contradictions come into a fuller interpretive dissolution from newly learned core beliefs (orthodoxy) and toward daily living (orthopraxy) within existing traditions, lifestyles, and cultural structures without losing heritage or traditions. A relativism of truth according to culture is not acceptable. As founded upon absolute biblical truth, it is essential to incorporate contextualized theology concurrently within friendships, general education, vocational instruction, poverty relief, shared resources, and collaborative efforts.

4. What are the issues with multiculturalism and in what ways should it be rejected?

An acceptance of multiculturalism is desirable to a limited extent. At the same time, it is imperative and more than necessary in support of Kingdom objectives.

A one-world homogenous praxis of cultural accommodation is an antithesis to multiculturalism. The temporary suspension of personal culture is also an antithesis to multiculturalism. However, Christ-centered theological contextualization across cultures must prevail as God is pleased with diversity and variety. A synergistic growth in Kingdom development founded upon biblical truth and justice is expected and necessary according to standards of Christendom (such as evangelicalism).

Within a multicultural framework, some societies or social movements can seek to impose ideologies upon evangelicalism that inhibit or destroy its effectiveness and drain resources better directed elsewhere. Multiculturalism should be a component of an overall strategy that does not exclude hostile ideologies but instead carries a reasonable probability of reaching its Kingdom objectives. Other features of that strategy should include existing political, defense, economic, and lifestyle influences as a collaborative effort with what God is doing on the world stage. Perhaps by attrition among some cultures less tolerant, by a measured effort elsewhere as likely successful, and where the return on multicultural activity is closer to the optimum.

Chapter Four: Diverse Perspectives and Theological Knowledge

1. What is meant by incommensurability? What is the difference between “strict” and “soft” incommensurability?

Clark states that Thomas Kuhn (1922-1996), an American philosopher, coined the term ‘Incommensurability’ to explain the notion of conceptual schemes or noetic structures that are closed off from each other, where there is no rational choice of the truest or best paradigm possible between them.

Hard (strict) incommensurability is where there is absolutely no contact between paradigms. Soft incommensurability, while still strict, is the claim that we cannot “evaluate two paradigms relative to each other by translating them into a third perspective without remainder or equivocation” (Clark, 137).

Further, Clark disputes the rationale concerning the differences as follows:

“If strict incommensurability were true, then each discipline would be utterly unique, and communication across disciplinary boundaries would be impossible. But such communication is possible. So, the various disciplinary horizons are not closed to each other but are instead open to each other. Disciplinary horizons or perspectives are not so unique as to be locked into their own ghettos of meaning.” (Clark, 184).

There is also a caveat of note:

On one interpretation, incommensurability, even in Kuhn himself, does not entail that the meanings of different paradigms are cut off from each other. Rather, incommensurability means that different paradigms focus on different problems and use different standards in solving those problems. In this understanding, we can translate the meanings from one paradigm into the terms of another paradigm. See the discussion in Richard J. Bernstein, Beyond Objectivism and Relativism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983), 85.

Clark rejected the viability of strong incommensurability while supporting a weaker version of it (Clark, 152). He argues that we must distinguish between the stricter and softer versions of incommensurability.

2. What is the difference between modernism and postmodernism? What do they have in common?

Modernism is the gospel of the Enlightenment as it views the human individual as liberated from external authority with autonomous reason who can discover absolute truth. Implementation of modernism, through rational planning, emphasizes standardization and science, leading to social progress (Clark, 141).

Postmodernism differs from modernism in that “worldviews, macroperspectives, and explanatory grids” do not rest upon universal human Reason. It rejects absolute truth.

Postmodernism values a plurality of perspectives, myths, cultures, and narratives. It is different from modernism as it distrusts universal Reason. Modernism affirms “individualism, anthropocentrism, patriarchy, mechanization, economism, consumerism, nationalism, and militarism.” Postmodernism rejects the dehumanizing power of modernity (Clark, 141).

Both modernism and postmodernism idolize freedom and individualism.

3. What is perspectivalism? Should evangelicals accept perspectivalism?

The heart of perspectivalism is the recognition that there are differences in the noetic structures of different people. More specifically, the nature of those differences gets at the heart of perspectivalism. Given, “the truth value of every belief is entirely relative to or completely dependent on a particular conceptual scheme, noetic structure, or web of belief” many accept this assertion as true. Different people have different versions of beliefs to hold true depending upon paradigm or worldview (Clark, 135). To say there is no truly rational choice between macroperspectives is possible is the heart of perspectivalism.

Evangelical theology cannot adopt comprehensive perspectivalism (Clark, 147). It should not be embraced but be kept at a distance with limited use and merit. While amended perspectivalism doesn’t confine Christian theology to its own intellectual prison, it is implausible overall. As relativism is closely related to perspectivalism, they are inconsistent at best and self-referentially incoherent at worst (i.e., all knowledge is relative to perspectives, worldviews, or paradigms).

4. What is foundationalism? Should evangelicals accept foundationalism?

Source-foundationalism, distinct from belief-foundationalism, is contrary to individual beliefs, as it is viewed as a collection of major sources of genuine knowledge (Clark, 153). It is a holistic methodology or a complex historical truth source.

Evangelicals should embrace soft foundationalism as it is a form of belief-foundationalism, and it accepts what is true about perspectivalism. It rationalizes effective epistemic practice leading to warranted belief, and “soft foundationalism allows evangelical theology to develop knowledge from its own perspective” (Clark, 162).

In contrast, belief-foundationalism is where individual beliefs are anchored as foundational.

By comparison, evangelicals should not embrace pragmatism or coherentism for various reasons that undermine evangelical theology. It must not embrace source-foundationalism that is of an Enlightenment period mentality that hungers for a source of perfect knowledge (Clark, 153).

Chapter Five: Unity in the Theological Disciplines

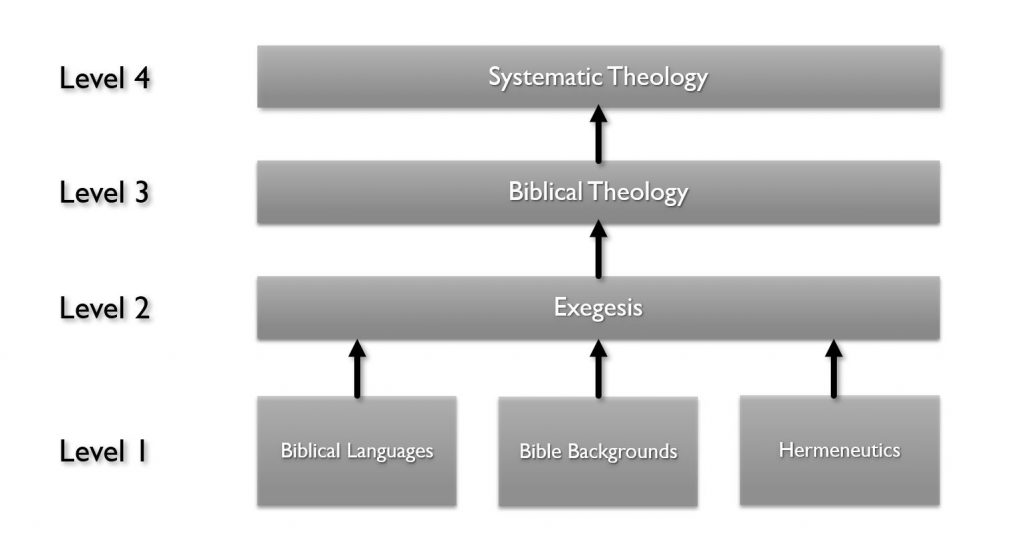

1. How would you distinguish the theological disciplines?

a. Historical Theology

Historical theology concentrates more closely on themes and theories across various historical periods (Clark, 169). It is a form of systematic theology immersed in the cultures of different periods during covenantal periods.

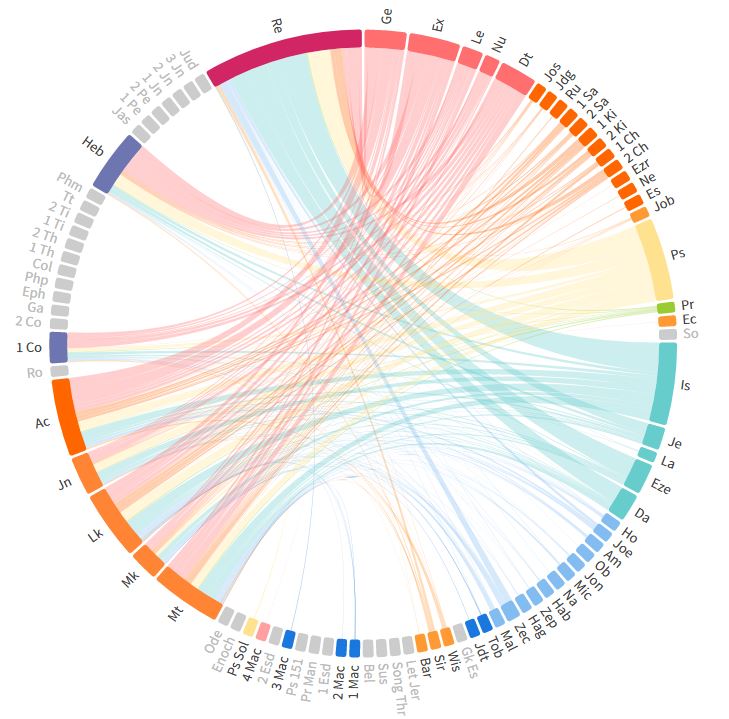

b. Biblical Theology

Biblical theology is any biblically grounded theology that rightly expresses biblical teaching or is correctly rooted in Scripture. Biblical theology is narrower in focus than biblical studies. It is faithful to Scripture. It recognizes the importance of literary and semantic theories around various genres of biblical languages. Biblical theology stresses the theological content of the biblical corpora as its subject matter. Unlike systematic theology, biblical theology limits itself to biblical materials, tracks the bible story, and organizes itself around a historical and chronological pattern (Clark, 170).

c. Philosophical Theology

Philosophical theology originates from Friedrich Schleiermacher, a protestant liberal theologian of the 19th century. It is an examination of theology built out of materials and thought outside of biblical data. It includes natural theology or data, which is derived from natural revelation or observation. An example of natural theology would consist of Thomas Aquinas’s five philosophical arguments for God’s existence (i.e., the Five Ways) as philosophical theology.

d. Practical Theology

Interpretation and application of theology arrive at practical theology (Clark, 190). A subset of systematic theology applies what Scripture says about communicating the gospel (Frame, ST, 1127; Frame, DKG, 214). Practical theology involves activity, practice, concerns, and disciplines for the unity, scholarship, and life of the church.

e. Systematic Theology

Barth defined systematic theology as a mode or method of human thought. His horrific experiences with socialism, and liberal theology initiated by Schleiermacher, reinforced his view that theology connected to the Word of God must be viewed as Church Dogmatics that originate from divine and supernatural revelation. Barth viewed Systematic Theology as the science of dogma.

It is an approach to the Bible that seeks to bring scriptural themes into a self-coherent whole from strict adherence to the authorial intent of biblical authors. Systematic theology is distinct from biblical theology, which comes from theological themes within individual books of the Bible (across both the Old and New testaments). The scope of systematic theology is wider to include biblical studies, church history, philosophy, and pastoral application.

2. How do evangelicals find unity in the theological disciplines?

Develop theoretical models of reason and a solid strategy to develop a unity of perspectives based upon truth from Scripture and what the biblical authors intended. The integration of different perspectives will resolve questions of unity in a comprehensive way bring into harmony issues surrounding interpretation. There can be no compromise of truth as that would be a betrayal of Christ, but a pursuit of unity upon a foundation of Scripture is a necessary bedrock.

As commensurate interests are understood around non-critical doctrines, there is plenty of room for the minor variability of tradition. However, core doctrines that arise from biblical truth must be adopted as the basis of meaningful and sustainable theological disciplines. It is unacceptable to rest upon a lowest common denominator approach to the theological disciplines.

3. How do liberals find unity in the theological disciplines?

For liberalism, the traditional view of the unity of theology, rooted in a realist conception of God’s revelation in the authoritative Word of God, is simply not an option (Clark, 179). Schleiermacher, a 20th-century liberal pioneer at Union Theological Seminary, proposed two solutions to the “problems” of status, legitimacy, and unity of theology and the intellectual pressures of the Enlightenment. More specifically, concerning personal and spiritual concerns of Christians. Liberal theologians reject all authority-based methods, and they seek unity from elsewhere.

The first solution proposed was that Schleiermacher introduced the “clerical paradigm” where pastors serve ordinary believers’ needs through legitimate scholarly enterprise. The second was an “essence of Christianity” motif as it is grounded in religious experience. Both approaches to the problems of liberals are a rejection of authority (i.e., the authority of Scripture or doctrines). He advocated for a shift away from biblical authority to that of intellectual independence. From a liberal viewpoint, it is impossible to find a unity of the various theological sciences by looking to the unity of divine truth. Liberals reject the evangelical answer—the movement from knowledge of God’s revelation to the practical application of that knowledge (Clark, 181).

Chapter Six: Theology in the Academic World

1. What are the values of academic institutions? Are these values consistent with Christian theology?

Dominant values of the modern university do not allow Christians to accept theological ideas as relevant to scholarship. Academic institutions of higher learning value a neutral approach where the discovery of knowledge demands that the knower be uncommitted to the object of investigation. This is the DNA of public universities. They require a knower to set aside whatever is accepted on the basis of authority and to operate according to principles of critical reason.

These values are not consistent with Christian theology as it seeks to maintain intellectual integrity within any academic setting. Theological disciplines need to both perform critically and also recognize biblical authority. As theology departments left academic institutions, universities replaced them with religious studies where scholars are not permitted to endorse any faith stemming from their discipline. Christian scholars and academics within the various disciplines of theology cannot separate their pursuit of truth, research, and discovery from revelation. The whole human is not merely natural and physical, but natural, physical, and spiritual.

2. What caused the move in contemporary universities away from theology and toward the study of religions?

Universities began to change the object of study from theology to “religious studies.” To detach any commitment of its professors, students, or scholars from a profession of faith, or commitment to revelatory truth from the authority of Scripture, academic institutions isolated themselves. They narrowed their efforts to critical methods situated upon human reason alone.

From the perspective of universities, Christian theology was lumped together with all other religions as a single homogenous whole (together with Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, and others). A single monolithic view of religions from liberal academics developed a view that Christian theology is fatally flawed because it cannot achieve the essential requirement of all scholarly work: freedom from all presuppositions.

Consequently, from a pluralistic perspective, universities embraced religion as the object of their study rather than God as the source of creation, natural order, physics, phenomena, hard sciences, and the like.

Theology is absent from public and secularized universities. Theology exists only in church-related universities, divinity schools, or seminaries. This institutional separation clearly reflects the common prejudices about these two areas of study and their relative value or validity (Clark, 203).

“According to George Marsden, the dearth of evangelicals in the secular university scene resulted as much from an evangelical exodus as from a secularist coup (Marsden, “The Collapse of American Evangelical Academia,” in Faith and Rationality, ed. Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff [Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1983], 219–264).1

3 What are the values of academic institutions? Are these values consistent with Christian theology?

Evangelicals follow a Barthian approach to Christian faith and living from a sociological standpoint, not theological to a significant extent. As evangelical subculture produced a range of social institutions like seminaries, colleges, denominations, hospitals, charities, media enterprises, magazines, and publishing houses, evangelical theologies functioned within this social context with some exceptions.

As academic institutions influenced churches and their members, the shift from divinity in academic achievement to scholarship began to pervade even Christian institutions. According to academic values, these scholars became detached as objective research was sought and conducted—which explains the dominant education of pastors. Seminaries and their members became insular and less connected to fellow believers in the church. Consequently, theological work from Christian academic institutions rendered its scholars and graduates irrelevant to parish life. The skills around the research associated with theological studies did not comport well with pastors’ performance and weekly duties. Thus, a push to develop professional pastors emerged to develop skills for practical ministry to serve the church.

_______________________________

1 David K. Clark and John S. Feinberg, To Know and Love God: Method for Theology (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2003), 203.

Chapter Seven: The Spiritual Purpose of Theology

1. Should orthodoxy be bounded-set orthodoxy or centered-set orthodoxy?

Christians who are anchored to biblical truth must hold to theological principles that are defined within bounded-set orthodoxy. Centered-set thinking and contextualization are useful models for purposes of outreach and missional functions. The rationale to operate a church from a centered-set model to suit cultural preferences and expectations represents a serious risk to error, heresy, and harm to people.

2. How does Clark make distinctions in theology as science and as wisdom?

Clark identifies the theology of science as scientia and the theology of Godly wisdom of sapientia. The distinction between these two forms of theology is critical. Scientia is limited where it informs the intellect about what beliefs and people are legitimately Christian and validate an orthodox position. Scientia plays a key role in determining if what a person believes is authentically Christian and orthodox.

Sapientia is the ultimate function of theology. Scientia serves sapientia as it informs believers what is true and accurate about theology to live out what God has revealed through scripture as aided by the Holy Spirit. The purpose of theology is to know God. Theology’s purpose as sapientia is conforming individual believers by the power of the Spirit to the image of Christ.

3. What should be the necessary relationship between theology as science and as wisdom?

Clark expresses the integration of theology as both science and wisdom through phases or moments (Clark, 232). There are five moments listed in sequential order as follows:

a. Engagement

Through various means, a person encounters through a variety of media. By people, circumstances, analysis, hardships, scripture, and other means through language and experience, a person engages God as truth becomes revealed for further interest.

b. Discovery

Imaginative thinking at an applicable scope is originated to form a working theoretical or conceptual model that comes from the creativity of a theologian. Biblical theology (revelatory witness) is conceptualized into a larger perspective from the creative imagination to theologically understand how biblical observations, theories, or doctrines emerge in a concrete or abstract way.

c. Testing

Testing is taken together with discovery as they work together to form meaningful conceptual models that are validated through a methodology to originate theological proofs. As scientists, or theologians who apply scientia, originate hypotheses, they turn to test and experimentation. This is to prove theories, models, and predictions or demonstrate them as false or invalid. Data is canonically sound from scripture as a primary source, but secondary means include history, tradition, literary work, or science that have less weight. Divine revelation has the sole authority over any other area of contribution that might add weight to test theological concepts.

d. Integration

This is the most important and crucial stage of processing a Christian’s relationship between theology as science and wisdom. At integration, scientia moves into the domain of sapientia. This is where theology moves beyond cognitive information to personal transformation as this phase of truth processing goes from intellectual to personal.

Just because someone is knowledgeable about theology or skilled in ministry, that doesn’t mean a religious professional is mature or growing in Christ. Without integration of truth, and only engagement, discovery, testing, a person is only accumulating knowledge. The intended outcome of scientia is to fulfill sapientia through the fulfillment of what to do in response. Theology is to change lives for the good through relationships and the transformation of people into Christlikeness. This fulfills theology’s proper role as sapientia.

e. Communication

The fifth phase of working with truth involves all forms of ministry service and leadership. From both abstract (precision) and concrete (power) theology (Clark, 242), the proper outcome is to express by word and action God, His will, and His ways. Where Christians love people and communities through communication as it uses theological truth to influence affections, decisions, and character (Clark, 243).

Chapter Eight: Theology and the Sciences

1. Does science threaten theology? If so, how?

Clark points out that the Scopes monkey trial has significantly influenced society to the detriment of Christian credibility and intellectual standing (Clark, 265). Not just concerning the sciences, but overall, as there is within secularism a stigma often attached to simple people of faith. Historically, and now, fundamentalism is further stigmatized because of its ridiculous conduct. There is an ocean of people on the Internet and in public life who are making assertions about theological and scientific concepts and principles they are not qualified to make.

Furthermore, with figures such as Thomas Huxley (1825-1895), who fought creationism through his aggressive advocacy of evolution, or from people in academia who produced scientific theories proven through scientific and empirical methodology, society has come to accept presuppositionalism, methodological naturalism, and rationalism from the scientific community. Between faith and reason, reason prevails in society to produce naturalistic and material thinking and benefits to humanity, such as in medicine, quantum physics, engineering, technology, biochemistry, etc.

According to the modernist view, science has won the culture over theology when it comes to rationality (Clark, 263). Science doesn’t threaten theology. Science and theology performed correctly complement one another. Theology, and biblical interpretation in error by translation issues, inferior literary analysis, false historical assumptions, church traditions, and many other limited capabilities of religious leaders, the laity, and individuals who think Scripture describes scientific facts are mistaken. The Bible isn’t a scientific text. It’s a text of literary, historical, and theological truth. It doesn’t contradict science, but science is antagonistic to those who use Scripture and make unfounded assertions without data or a necessary background to suit personal opinions or interests. People of faith who do not have a well-developed capability of quantitative, qualitative, and capacity for analytical reason with the disciplines often really have very little to contribute.

2. In what ways can science and theology relate? Which is best and why?

The Clark text presents two major subsections under “The Rise of Science and Its Challenge to Theology.” These are with respect to how science challenges theology. To his words, “So how should we conceptualize the relation of science to theology?”

a. Science as a Rational Idea

b. Science as Cultural Authority

From an objectively neutral perspective, “Science as a Rational Idea” is the best between these two approaches. Because observations, experiments, discoveries, and the scientific method take a dispassionate matter-of-fact objective approach to science. Large because there is no room for cultural and religious subjectivity. Including the world of theology among a wide range of academics, seminarians, theologians, and laymen, which is too often an unstable Wild West of meaning and coherent thought.

Scientists, engineers, and technologists who accept biblical truth can participate in scientific endeavors. While having a theologically centered rationale and worldview, but not to the extent that irrationality or incoherent thought is disruptive, harmful, or in betrayal of truth. God created logic, induction, deduction, and abduction for His purposes.

Clark goes on further to make comparisons using categories of the relationship between science and theology. Terms are given for these categories as follows:

a. Conflict

b. Compartmentalism

c. Complementarity

Among these, complementarity is best. There are various reasons to conclude that this approach is most suitable or productive. Within the various fields of science and theology, dedicated areas of focus are more attuned to the realities that exist to describe functions, properties, behaviors, and the like. Separately, there are more limited outcomes and benefits of understanding and application, but together they yield a synergy that produces a fuller cognitive use and thinking of a subject.

3. What are the positive and negative aspects of methodological naturalism?

Positive:

Methodological naturalism is a legitimate assumption for the large majority of research programs (Clark, 280).

Negative:

Methodological naturalism rules out all allusions to spiritual forces (Clark, 280).

4. From an evangelical perspective, what relationship should science and theology have?

Theistic science should be the context or framework by which science and theology relate. Science, as a human discipline of method and reason is incapable of overriding the authority of the Bible nor is it permitted to for its own purposes. While science is always subordinate to theology, it can supersede interpretation while scripture remains the authority of truth.

There should be an advocacy for dialog where both science and theology are able to communicate in an effort to attain open integration between the two. Theological claims and scientific models and naturally described realities are not in contradiction to one another when considering proper perspectives (Clark, 284). Various frames of reference on reality to get at unified truth is achievable in a post-modern world that is skeptical of both theology and science.

Christian theology explains why science matters. It doesn’t resort to a God-of-the-Gaps rationale, where “the absence of plausible naturalistic rationale of some phenomenon is always sufficient to conclude a that a particular natural event does not itself suggest, let along prove, the presence of personal agency” (Clark, 289). It is never acceptable for Christians to rely upon a God-of-the-gaps rationale to explain scientific reason or uncertainty. Any lack of scientific evidence is not explained by God-of-the-gaps.

Chapter Nine: Theology and Philosophy

1. Are there senses in which philosophy or human reason can aid theology?

A warning to beware of philosophy (Col 2:8; cf. Eph 5:6, Col 2:23, 1 Tim 6:20), or philosophical systems (sophos philos).

“See to it that no one takes you captive through philosophy and empty deception, according to the tradition of men, according to the elementary principles of the world, rather than according to Christ.”– Col 2:8 NASB

BDAG:

φιλοσοφία, ας, ἡ (Pla., Isocr. et al.; 4 Macc; EpArist 256; Philo; Jos., C. Ap. 1, 54, Ant. 18, 11 al.) —“philosophy, in our lit. only in one pass. and in a pejorative sense, w. κενὴ ἀπάτη, of erroneous teaching Col 2:8 (perhaps in an unfavorable sense also in the Herm. wr. Κόρη Κόσμου in Stob. I p. 407 W.=494, 7 Sc.=Κόρη Κόσμου 68 [vol. IV p. 22, 9 Nock-Festugière]. In 4 Macc 5:11 the tyrant Antiochus terms the Hebrews’ religion a φλύαρος φιλοσοφία).” 1

Students and scholars make use of philosophy in at least two ways. Both “philosophical theology” and “philosophy of religion” are together the study or disciplines of religious belief and life to include psychological, sociological, historical, or literary approaches. To use Clark’s words, “They focus on the meaning of and the truth states of religious beliefs” (Clark, 297). Philosophy is an instrument of thought or method of human reason to help understand or recognize the plausibility of religious beliefs and their truth claims. Clark further develops three senses of reason by the strict expression of the word with respect to divine revelation.

a. Autonomous Reason

Intrinsic reasonableness is set as a critical stance against authority for prescribed autonomous judgment, critical reflection, and skepticism.

b. Knowledge Capacity

Inherent ability to derive and produce knowledge. Simply the ability to think. “It is the divinely created capacity to understand God’s revelation both in the Bible and in the world” (Clark, 299).

c. Noetic Equipment

God-given inferential equipping that each person is endowed by or hardwired to recognize by reason of God’s revelation.

2. How do presuppositions operate within a Christian worldview?

Presuppositions that stem from modernist sensibilities do not comport well with a biblical worldview. Inductivism is a traditional, erroneous, and implausible philosophy of the scientific method. It seeks to develop scientific theories and neutrally observe a domain or states to infer laws from examined cases—hence, inductive reasoning—to objectively discover the observed’s sole naturally “true” theory.

Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920) was a neo-Calvinist theologian who established Reformed Churches who reasoned that inductivism is insufficiently aware of the controlling influence of presuppositionalism.

Van Til’s perspective informs us that a brute fact is a mute fact. This contradicts the inductive science view, where uninterpreted facts do not lead straight to authentic knowledge. Presuppositions are embedded into perspectives as knowing shares nothing or has no common ground between people with different worldviews. Clark further writes that the Christian worldview is the correct worldview centered on God and His revelation within Scripture.

Clark outlines the meaning of presuppositionalism as a belief as it correlates to a system of thought (Clark, 309) where knowledge is assumed true without justification or a process to give its explicit and true meaning.

3. Are there different worldviews and can they be warranted?

Different worldviews exist, but aside from Scripture, they’re unwarranted. The Bahnsen paper Clark references (pg. 309), “Inductivism, Inerrancy, and Presuppositionalism,”2 makes it clear that presuppositionless impartiality and neutral reasoning are impossible because Scripture informs us that all men know God, even if suppressing the truth (Rom 1). There are two philosophic outlooks, one according to worldly tradition and the other to Christ (Col 2). There is a knowledge that is erroneous to the faith (1 Tim 6), and that genuine knowledge is based on repentant faith (2 Tim 2). In contrast, some people (unbelievers) are enemies of God as they are hostile in their minds (Rom 8:7) while others (believers) are renewed in knowledge (Col 3:10).

Clark further stipulates that no one comes to warranted belief by simply observing facts because facts will always depend upon perspective.

The enemies of God are unable, who suppress the knowledge of the truth by an adopted presuppositional worldview stemming from the perspective of the world cannot be subject to God’s Word (Rom 8). They see it as utterly foolish and view it with contempt (1 Cor 1), while people who subject themselves to God’s Word take every thought to the obedience of Christ (2 Cor 10). Further, in the words of Bahnsen, “Presuppositionless neutrality is both impossible (epistemologically) and disobedient (morally): Christ says that a man is either with him or against him (Matt 12:30), for “no man can serve two masters” (6:24). Our every thought (even apologetical reasoning about inerrancy) must be made captive to Christ’s all-encompassing Lordship” (2 Cor 10:5; 1 Pet 3:15; Matt 22:37).

_______________________________

1 William Arndt et al., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 1059.

2 Greg L. Bahnsen, “Inductivism, Inerrancy, and Presuppositionalism,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 20 (1977): 300.

Chapter Ten: Christian Theology and the World Religions

1. How are the differences between descriptive and normative pluralism described?

Pluralism can be viewed as a sociological force as it is descriptive of various religions that exist within a region or population. By comparison, pluralism as a normative or prescriptive idea is an interpretation of religious diversity where all its expressions lead to God. The notion that all religions are true faiths that ultimately lead to God. It’s a theory that all methods and beliefs are on different paths to the same outcome.

2. How does the author make distinctions between altheic and soteriological issues?

Clark refers to Alvin Plantinga’s alethic question about the truth of religious doctrines. And whether religious teachings in question actually exist. “Alethic” is from the Greek aletheia, meaning “truth.”

By contrast, John Hick places interest upon the extent to which each religion actually experiences salvation or liberation. These are soteriological questions that ask questions and definitions concerning actual salvific merit and if they all are separate paths to God. “Soteriological” is from the Greek soteria, meaning “deliverance,” or “salvation.”

3. How does the author make distinctions between altheic and metaphysical realism in religion?

Metaphysical realism is a sub-category of alethic realism as alethic realists are certain that metaphysical reality exists. The distinction with the alethic realist concerns the doctrines that describe and point to ultimate spiritual existence.

Metaphysical realism corresponds to the view that an actual spiritual Reality exists independent of human thought and speech. There is a spiritual realm to affect religious or spiritual experience where such experience is caused by a mind-independent Reality external to thought or reason.

4. How does the author make arguments against realist pluralism and and nonrealist pluralism?

Clark presents two approaches to Realist and Nonrealist approaches to pluralism. He frames his discourse about pluralism, realism, and evangelical theology around John Hick (Realist) and Gordon Kaufman (Nonrealist). Both individuals support pluralism, which is untenable from an evangelical theology perspective, but Hick connects pluralism to metaphysical realism, and Kaufman makes the connection with metaphysical nonrealism.

With extended prose and tedious detail, Clark makes an intricately elaborate and lengthy effort to disassemble the views of both Hick and Kaufman. With various nested and interwoven thoughts, Clark precisely drills into numerous objections to the conceptual arguments against Hick as antithetical to fundamental theological truth. Namely, his Kantian theological agnosticism and alethic nonrealism (Clark, 333; (e), (f)). Attempting to make coherent sense of Hick’s views, Clark elaborates on his background to make connections between Schleiermacher, Kant, and others to form errant thinking about theological truth. That is a preference for an individual’s personal religious experience. Without reference to the Holy Spirit’s work, revelation through Scripture and His presence per se is therefore speculative and subjective to Hick without weight.

Within the Clark text, both Hick and Kaufman fail to accept the contradictory nature of the doctrinal claims of the major world religions. Their claims of salvific truth are opposed to one another. Each has its peculiarities where personal religious experiences are significantly different in terms of what is involved in setting about the right path toward God. As an impersonal or personal God among the numerous religions would have expectations toward Him in a Real way, those expectations would not be self-contradictory as implicit by Hick’s and Kaufman’s pluralism.

The further discourse about noumenon (Reality as it is in itself) and phenomenon (Reality as it is for us) again redirect interests and requirements of what is involved in a salvific or liberating return to God as centered upon the person. Not the true God of a metaphysical realism grounded in an explicitly inclusive set of circumstances, conditions, or epistemologically and biblically coherent worldviews. Schleiermacher is written all over the thinking of Hick and Kaufman.

As Clark more explicitly turns his attention to Kaufman’s nonrealism position. He outlines Kaufman’s position that humanity cannot experience God directly. Moreover, Kaufman states expressly that God and theology are constructs of human imagination. In contrast, it is only by human terms or referential understanding or comprehension that God exists. As if there is an obligation from somewhere or all religions to derive the Creator on human terms, not by what is posited as pluralistic nonrealism. In other words, religious people all desire to imagine a Being that isn’t real. Kaufman advocated ultimate humanity, where theology and thus pluralistic thought, through all forms of God and religious belief, were in service of a greater or better mankind or humanization.

5. How can Christians be exclusivists and still tolerant?

While Clark writes that, according to contemporary sensibilities, religious tolerance requires the adoption of pluralism (Clark, 349), there are a couple of ways in which authentic Christians are “tolerant.”

a. Among Christians, there is an expectation of openness toward others with whom one disagrees. It is possible to tolerate a naturalist perspective, but more importantly, as followers of Christ, Christians are expected to abide by His instructions to love even enemies. Not by ignoring another person as a position of tolerance, but by loving others actively regardless.

b. It isn’t always plausible to agree with those who have a naturalistic perspective contrary to Christian views. However, it is necessary to accept each person’s right to defend their views with respect in spite of any disagreement over belief or behavior.

Chapter Eleven: Reality, Truth, and Language

1. How would you describe truth?

The Clark text covers a lot of ground around the question of truth and its definition. On the one hand, he calls it “factual certainty” (pg. 373). On the other, he elaborates, “Truth is constituted by correspondence of linguistic utterances to mind-independent states of affairs: around the topic of correspondence theory (pg. 381).

More explicitly, Jesus said that He is the Truth (Jn 14:6), and by extension, all that He says and does is truth. When Pilate asked, “what is truth?” Jesus answered to generations who He is, what He has done, and what He is doing as a matter of reference that serves as an anchor. The absolute certainty of meaning, physical being, and alethic metaphysical reality has substantive concrete and abstract definition to the Creator God where truth and wisdom belongs.

2. What is the nature of truth-bearers? What kinds of things can be true?

Truth-bearers accept truth value as propositions and statements. They also accept and embrace personal truth as associated with the identity of persons (e.g., Christ).

Propositions, abbreviated propositions, statements, opposite truth values, mood, tone, and mind-independent reality from language or linguistic expressions are what things that can be true, and states of being that can be true from absolute revealed meaning and condition, or historical and cultural contexts. Truth is absolute and not relative to social or individual preferences or historical and cultural contexts.

3. Describe the differences between correspondence theory of truth and coherentist and pragmatic theories.

a. Correspondence Theory of Truth:

This is the embodiment of core intuition “according to which the word ‘true’ modifies utterances that adequately connect to and depict aspects of a mind-independent world” (Clark, 363). It is a way of saying that the truth of statements or propositions matches the actual world.

There are conditions of metaphysical and justification propositions that exist and point to alternatives among philosophers to advocate coherentist and pragmatic theories. Clear ideas that correspond to reality define truth, and it answers metaphysical realism.

b. Coherentist Theory of Truth

As one stated alternative to correspondence theory, it can be considered a denial of correspondence theory. It is the practical application of propositions that justifies and accounts for the definition of truth. This is not a theory of truth but a theory of warrant or justification (Clark, 366). This, as a theory of truth, is false.

c. Pragmatic Theory of Truth:

As another stated alternative to correspondence theory, it attempts to redefine truth in terms of its usefulness. It is a theory that attempts to advocate metaphysical nonrealism by inference. It is a way to view the distinctions as true or useful. What is useful can be true, but not everything true is useful. It doesn’t capture intuition or instincts about the nature or properties of truth.

4. How does the hermeneutics of suspicion and finitude of post-structuralists and deconstructionists challenge truth claims?

Deconstruction involves hermeneutics of suspicion and finitude to disintegrate truth as having authoritative meaning and absolute value. Deconstructionists claim there is no such thing as reality itself, only interpretations of reality. They believe or think that certainty is not possible. They also think that binary classifications and categories such as part/whole, inside/outside, good/evil, nature/nurture, male/female, true/false do not capture objective reality.

Clark informs his readers that “deconstructive postmodernism overcomes the modern worldview through an anti-worldview. It denies the elements necessary to any worldview, including concepts like God, self, and truth” (Clark, 373). While poststructuralism is a weaker form of deconstruction, they both reject the Enlightenment’s views of neutral objectivity, absolute certainty, and straightforward answers. Deconstruction abhors truth, and it seeks to dismantle objective and authoritative reality from the roots of linguistics.

Neither of these strategies’ challenges to truth claims is valid because they rely upon definitions from language to achieve an order of understanding. They borrow on the purpose of intended meaning to achieve their objectives. They’re self-refuting, or self-referentially incoherent.

Chapter Twelve: Theological Language and Spiritual Life

1. Distinguish univocity, equivocity and analogy in religious language.

Clark opts for limited univocity, but he recognizes the need for Analogy and its use in Scripture. While he makes distinctions about the univocal and literal use of language, he elaborates upon numerous examples where both are applied and true during the use of language. While Clark agrees with Aquinas that equivocity leads to agnosticism, he also supports the assertion that Analogy has its suitable theological place up to a point. Clark is concerned about Aquinas’ Analogy of proper proportionality because of how words function as modes of being, action, thought, or language. Clark wrote that Analogy, according to Aristotle, is a form of equivocity (Clark, 390). More specifically, there are ambiguities about what we can understand about God. Theology, on its own, does not help us understand or know God.

Clark makes it clear that the difference between the meaning of terms between God and the creature is the distinction between univocal and analogical predication. The literal or univocal sense is the default meaning to us as a one-way frame of reference. So, the function of analogy isn’t to inform but to place restraints upon the proper use of language when it comes to “theistic systematic assumptions.”

Clark’s use of the term “infinity,” when set alongside transcendence, and corporeality, presupposes the presence of time, as God exists or operates within it without beginning or end. Such a distinction seems to reveal confusion about what transcendence is. Where time is a created construct of God outside of time or within it as He so chooses or intends. In Clark’s view, attribution in this univocal sense isn’t as helpful, but I overall agree with his position about the univocal use of language to understand and know God. Especially when it comes to the use of Scripture and God’s self-witness about what we can know about Him in a way that corresponds to what we can grasp or accept by alethic and metaphysical realism.

2. What values and distinctions of speech-act theory are referenced to the language of the Bible?

Types of spoken language, or utterances, and the use of words to express or describe something is different than what it is to do something by perlocutionary or illocutionary force. They’re together spiritually formative, so long as the objects of their intended use are actual. So, it is okay, and expected, within modern people and churches, to express worship, praise, instruction, exhortation, rebuke, encouragement, and so forth that comports with the language of the Bible. Figurative, metaphorical, and literal meanings that contribute to the working of sapientia in our lives are suitable to the extent precision or more descriptive, or reasoned accuracy is warranted.

There is explanatory value in expressions in the types and distinctions of speech-act theory as propositions and statements carry collaborative, informative, and cursory forms of meaning among creatures to accomplish what both the Creator and creatures want to relate and share experiences. Fellowship, shared witness, prayer, worship, instruction, with words conveyed to form communicative acts shape what people and their Creator say, hear, and do.

Therefore, language is intended to accomplish something. Verbal utterances do something other than merely informing people about sense and reference, according to scientia. It serves the purpose of sapientia to worship the triune God and transform Christian character (Clark, 417).

Conclusion

Clark offers numerous point-by-point instructions, admonishments, and areas of guidance as he brings his book to completion. Taken together, they serve as a formulaic way of executing a strategy toward developing a theologically well-grounded sapiential Church. He touches upon personal, interpersonal, and social relationships that extend to individual disciplines, visionary thinking, polemical engagement, rigorous theological discipline, relationships, biblical social justice, and outreach. His final words were about the essential and compelling urgency to know and love the true and living God.

From 2021, approaching two decades ago, Clark’s book To Know and Love God was published. While it dates back to a different time of evangelical thought and discourse, the methods and principles around theology still hold and are relevant today. By surveying the range of chapters that comprise the book, the reader sees a common thread where the author forms layers of sequential content. The material within the book isn’t organized as a mosaic of theoretically practical methods around the study of theology. It is written cohesively to bring predicated order and rationale to the study and application of theological methods and principles.

While the text is highly concentrated with the theological and philosophical subject matter, it carefully crafts a coherent message. Not just at the most granular level but structurally as well. The chapters, book sections, and subsections are interwoven and complementary to one another to reinforce and provide a full-bodied depth. The book’s organization is well thought out as it is apparent that the author wanted to offer God and His people the best of his work. The book is very technical, but it communicates to the reader personally with relatable stories and content to instill confidence and retention.

The book begins with general concepts around the topic of theology along with some of its history and key figures during its development in the 20th-century. The forms of study and discipline about theology are covered with substantial attention to detail to include key influential figures from traditional and liberal or socialist backgrounds. Themes and concerns among historical theologians toward the modern era were at length explained to give a greater sense of context about the reading ahead. The tension between a God-centered theological approach and anthropocentrism began as an outright situation to grasp, and it remained a constant subtext through the remainder of the book.

As Clark continues through more rudimentary principles to set a baseline, it was necessary to cover essential matters around the authority of scripture, culture, and a diversity of perspectives. The author relies heavily on philosophy, historical rationale, and contemporary issues to assert what theological propositions to value and hold in support of evangelicalism. He cites numerous academic and scholarly sources to support his conclusions and offer reinforced thoughts concerning premise after premise that gave order and clarity about where he guided the reader. Clark did not just give the details about perspectives from academic individuals, theologians, and philosophers. He reached into the nuts and bolts of theoretical approaches to the subject matter.

To match the depth of the book, Clark covered a wide span of topics about theological methodology as well. Along with the various epistemological and ontological concerns about interpretation and belief, the numerous forms of theological disciplines were presented for a reader to understand their place and unity as a body of material. Set adjacent to each other, the sciences, philosophy, and theology within the academic, secular, and religious worlds were illuminated to bring out the purpose, justification, and necessity of Christian belief. Not for apologetic reasons, per se. Rather to think well about Christian theology while people seek to live lives of loving and knowing God with their entire being.

In an effort to contrast Christianity to other world religions, Clark establishes the philosophical ground for new and existing theologians to understand and engage in discourse within the postmodern world. Specifically, contentious issues around pluralism, realism, subjectivism, exclusivism, inclusivism, and metaphysical epistemologies were compared and navigated to render sensible theological approaches to develop an “alethic truth” around a physical and spiritual realism that has a soteriological effect on humanity.

At the core of the text is the spiritual purpose of theology. This is the most substantive area of the entire book (chapter 7). The relationship between science and religion is explained in crucial detail as scientia and sapientia. The reader is given a step-by-step walkthrough of moments or phases of forming, applying, and communicating theological facts and principles to live transformed lives with others before God. Clark makes it abundantly clear that theology as purely an academic endeavor doesn’t reach its intended purpose or potential without internalizing what the theological method does (i.e., engagement, discovery, testing, integration, communication). The text does an exceptional job of explaining what theology is about and why it is of utmost necessity to live by what it produces within people.

Just as the text is titled and captioned, this is a book about knowing and loving God. It gets into significant technical and reasoned depth about what that specifically looks like. It is an important and necessary book to undergo and support continuing theological coursework.