Reaffirming Inerrancy, Christian Thought, and Pastor as Theologian

2016 Shepherd’s Conference Seminar

Notes of Abner Chou lecture from the following source: https://www.gracechurch.org/sermons/11849

We are entrusted with the legacy of truth. To reclaim our position and function as Christian thinkers and pastor-theologians. To defend the faith. To encourge us and challenge us. To proclaim the unique and exclusive God of the Word.

The apathy of scriptural truth leads to a crisis among the youth and churchgoers. Truth and thinking is not important or relevant among churches. Sunday school teachers do not place much importance on this. Consequently, there is immense biblical illiteracy. We are in a crisis of truth.

Inerrancy is a thinking man’s doctrine. It claims that whatever the Bible asserts is true, so we must find the truth in terms of thought and its consequences. Such as its sufficiency, purpose, application, etc.

The Church refuses to think, and they do not want to think. Their preferences are elsewhere, so they reject inerrancy. We are in a crisis of truth. Society at one time respected Christianity, but now it has changed. Because it no longer recognizes the supernatural, but only the natural. Only science and their own thinking redefine the values we have. They are on a campaign to change every single value that the Bible upholds. Society has chosen to upend the truth.

Society views those who value truth by the inerrancy of Scripture as crazy, wrong, and evil. They want to remove us from society, and people in the Church want the same. Especially young people in Church and among those who leave. In general, people of the Church do not believe that the Bible is the exclusive truth. They doubt the sufficiency of Scripture. They are skeptical. They do not believe that truth matters. They don’t care, and it is irrelevant to them. This is the crisis of truth.

It is necessary to take a stand now. Otherwise, the Church is relegated to nothing with catastrophic results for the American churches and everywhere. So we must show our devotion to truth and thinking by declaring sophisticated answers on the whole counsel of God and defending against error.

We must live up to what inerrancy demands to help people recover the doctrine of inerrancy. To help our people value the necessity and beauty of the doctrine of inerrancy.

The Three Demands Scriptural Inerrancy

- If we affirm the Bible is truth, we need to be devoted to truth and thinking.

- If we affirm the Bible is truth, we need to declare answers from the whole counsel of God’s word.

- If we affirm the Bible is truth, we must defend against inerrancy.

1.) If we affirm the Bible is truth, we need to be devoted to truth and thinking.

We need to be equipped to have answers and make the case where others will have conviction. To study it and develop a passion for it. Necessary to regain the compelling importance of inerrancy.

Two important questions we must answer:

a.) Is the truth powerful? Is the Bible authoritative?

It is necessary to debunk the idea that truth is merely information. Truth goes far beyond that as it acts upon a person’s life, will, and intentions. Truth includes information, but it is more than that. Scripture itself proclaims that Jesus is truth, and the truth shall set us free. Jesus is the way, the truth, and the life (John 14:6). The truth through His word is the extension of Christ, His activity, power, and effectiveness.

John 1:14, Jesus is declared full of grace and truth. He speaks a message of truth in John 8:40 & 45, “because I speak the truth, you do not believe Me.” Truth causes people to walk in the truth (3 John 1:4), worship in spirit and truth (John 4:23), and have life (John 14:6). Truth sanctifies (John 17:17), and it sets people free (John 8:32).

Toward the end of Jesus’s ministry, He appears before Pilate to testify to the truth. This is what He said before His sacrifice. Everything made right by His redemptive plan of the gospel is linked with truth. Truth is powerful, dynamic, it saves, and it gives life. Moreover, truth is liked to God’s definitional authority (Genesis 1 -3). In that knowledge, wisdom, and truth is an issue. There God established in the garden “the knowledge of good and evil.” God alone has the right to define what is right and wrong.

As depicted by Solomon, truth is linked with the culmination of God’s plan as people sought his wisdom. In Isaiah 11:6-9, Eden is regained when truth prevails.

We need to remind people about the origin of truth and its reality. If you want to make a difference and have an impact on people’s lives, then preach the word and proclaim the truth. Truth is not just information.

Truth is exclusively found in Scripture alone.

Contradictions from the culture that proclaims otherwise about social issues are not valid. Culture does not know better than the truth of Scripture. We need to remind our people of this and make a case for it. In Job 28, God Himself argues for the supremacy and exclusivity of His word. As Job was written as the first book written of the Bible, the design and purpose of Scripture is recorded to introduce the need for His word.

Suffering provides a window into greater questions. It destroys your sense of understanding this life and that you can handle it.

Truth is a matter of life or death, heaven or hell. Key verses of Job 28:12-13 articulates this meaning, “But where can wisdom be found? And where is the place of understanding? Man does not know its value, nor is it found in the land of the living.” It is impossible for humanity to know the full picture or answers of truth and wisdom in life. Wealth and riches cannot manage life adequately enough to assuage suffering. Nor can skill, or competencies as further proven in Job 28. –Man doesn’t have the capability of originating or deriving wisdom.

God says in Job 28:23, He alone understands its way, and He knows its place. God is the only source of wisdom. When Solomon said, “the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,” he was referring back to Job. Where this phrase is found in Psalm 111:10 and Proverbs 9:10, so to remind people that they don’t know better is necessary in light of Scripture. It is impossible. It needs to be repeatedly paraded before the Lord’s people, that they do not know better than what is given in Scripture, or the wisdom of God by His word.

The first written book of the Bible in Job establishes the wisdom of God by His word and how the world works because He has seen and defined it all.

b.) Is truth what we do? To think about the truth?

Thinking about truth is what drives the Church. It is a sacred task sent by God throughout redemptive history. As given by examples of the prophets, who were adept at God’s word as Scripture, they were immersed in the meaning of what God’ revealed throughout history.

Various books of the Old Testament are interconnected where there is an understanding of God’s word and His revealed wisdom. It reveals that God cares, and we anchor our soul in that for significant shepherding applications. Theologically speaking, we have highlights of examples given by an illustration of a vine over the course of millennia. Whereas the vine represents the Lord’s people, Israel.

Walking back from the parable of the vine that illustrates and assesses the state of Israel’s spiritual state of existence:

Psalm 80: Strong Vine

Isaiah 5: Vine Produces Bad Fruit

Jeremiah 2: Vine that is Degenerate

Ezekiel 15: Vine that is Useless Except as Fuel for the Fire

Whereas thereafter in John 15:1, Jesus says, “I am the true vine.” Do not lose hope, but rely upon trust in Him. So the prophets were theologians who saw the truth of Scripture. What’s more, Jesus Himself was far more advanced in His use and understanding of Scripture. For example, after example, He makes the point about the truth of Scripture to condemn, teach, and enlighten.

Thinking drives the Church forward. That’s what we do. Just as we see from Paul, the Apostle in the Epistles is proclaiming the word of truth. For the entire Church everywhere and for all time (2 Tim 4:19-22). Grace be with you as written in 2 Timothy 4:22 is stated in Greek as plural. Paul’s prayer was for us. He prayed that we would communicate the truth as He did and just as our Lord Jesus did.

So our objective is to share and drive a conviction about the truth of God’s word and what it does. About what it is for and its power, that by doing so, we erode and eliminate Biblical illiteracy. From cover to cover, we all understand and have convictions about the word of God.

As theologians, we are not marketeers, therapists, or CEOs. We need to remain deeply engaged in Scripture. We need to know the original languages, find exegetical insights, and become adept at intertextuality. Furthermore, our reach should extend to systematics and issues. Aggressive reading beyond practical ministry (while important) is necessary in the areas of deeper theology. That results in greater breadth and depth surrounding Scripture. By doing so, we become a major theological resource to people (i.e., truth, wisdom, scriptural points of interest). This is the nature of being a Christian thinker and theologian.

Practical Implications:

- If you aren’t shepherding people to love truth, you’ll never be a pastor-theologian. Because your people will not understand what you’re doing. They must develop and have an appreciation of Scripture.

- Reach for and attain a deep engagement with the Scriptures. Necessary to take every thought captive to the obedience of Christ. Otherwise, without this engagement and devotion, our inerrancy is meaningless.

Paul in 1 Timothy 3:15 says that the Church is the pillar and support of the truth. So it is hypercritical that the Church has substantive engagement and thinking about the word of God. This is our role.

If the Church doesn’t do its job, it loses its testimony. So when people see and not just hear our devotion and dedication to Scripture, they will conclude there is nothing like the Bible. It is the exclusive repository of the truth. It is powerful and produces history.

2.) If we affirm the Bible is truth, we need to declare answers from the whole counsel of God’s word

The Bible is consistent and interconnective. There is a compounding depth to it. So we should have answers that reflect this reality.

If, in our answers or use of Scripture, we say, “Because the Bible says so,” that is not good enough. If we do not show the depth of Scripture, we do not demonstrate the whole counsel of God’s word. Where if there is a crisis of truth, life results are harmful and deadly. So as without providing depth, we confirm skepticism among people who already struggle to believe if at all.

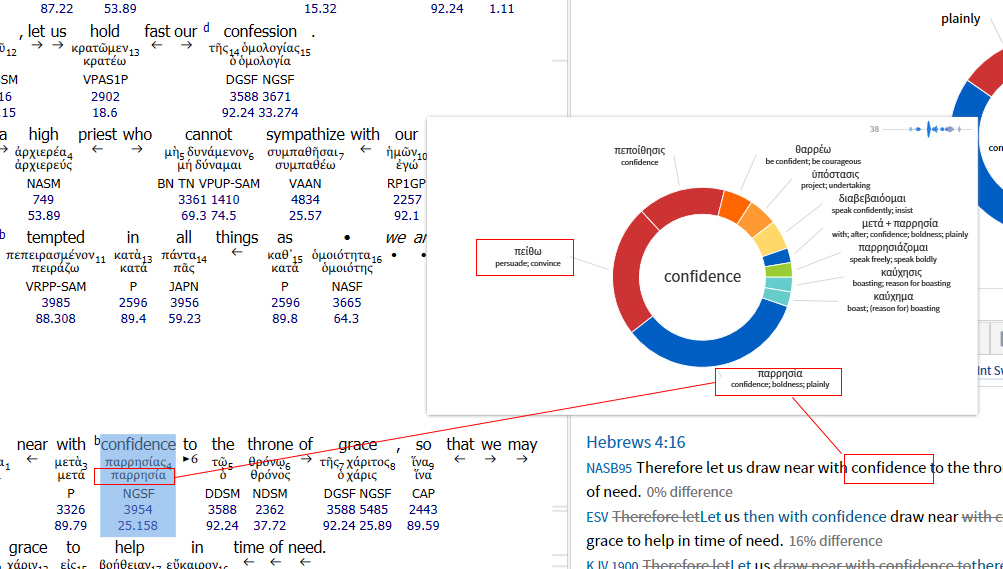

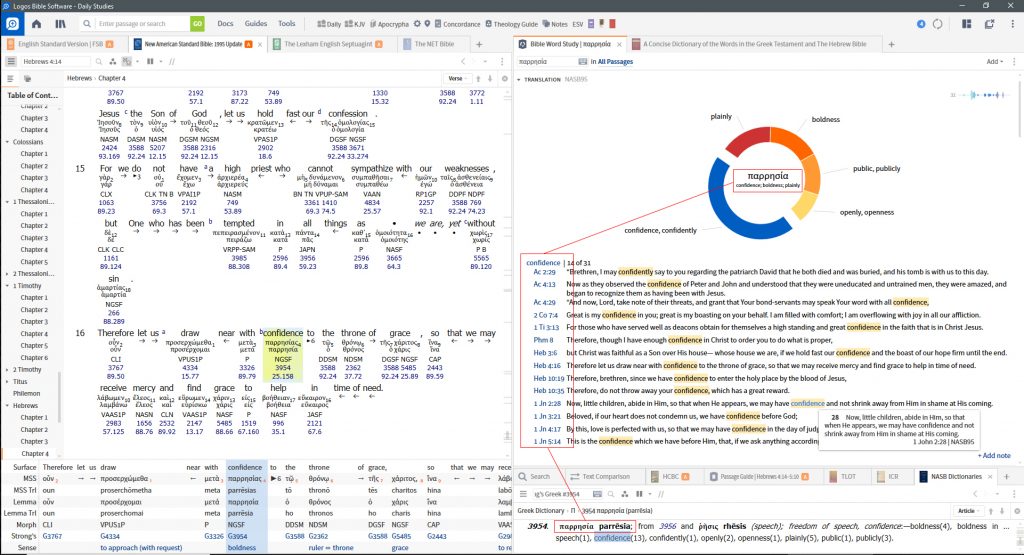

The whole of Scripture entails the entire counsel of God’s word. All the way down to single individual words or terms. As examples, to reveal and affirm terms such as deity, resurrection, rest, hope, theology, and shepherd — every word matters.

The apostles and prophets quote from a wide expanse of Scripture to demonstrate that they knew God’s word. Every passage is connected in Scripture. We use it to demonstrate that ordinary faithfulness is profound.

Why should we go to church? Why should we serve in the church? For fellowship and to exercise our gifts in support of the church. In that, we are the new humanity after the fall, according to the full counsel of God’s word. The extent of social issues is spoken to about marriage, incest, sexuality, at full depth, and breadth to reflect God, His love, and the identity of Christ.

So to engage and share the word of God, we are to articulate and demonstrate its truth as it pertains to the gospel, God’s covenants, His love, and the status of people according to their life circumstances. We need to give profound answers from the enormous facility of the text. So in that the Bible is sourced to do that, we teach others that the Scripture is truth. This is what inerrancy demands.

3.) If we affirm the Bible is truth, we must defend against inerrancy

This is what Scripture asserts as the difference between error and truth (1 John 4:6). The Scripture often attacks error, and as such, we use what it reveals to do the same. To walk through the errors that surface, we recognize that evangelicals have become post-modern (i.e., it’s all relative, pluralistic, & unclear). To accompany platitudes of “we just need to tolerate and love each other.” The descent goes further from among leaders such as “well, there are a lot of views,” or “there are a lot of interpretations,” and “the Bible is not clear, or that’s just not essential.” So with post-modernism comes confusion through the proliferation of subjective views. As Christian thinkers and theologians, we need to cut through all of that and provide clarity with reasons arising from the depth and breadth of Scripture.

As recovery goes from a post-modern attitude to a Biblical attitude, we remind people that truth is not relative. God’s word is the exclusive repository of truth. The Bible defines truth and error, and it is clear. God’s revelation is something that was hidden but has now been made accessible. It is literal, historical, and grammatical. The Bible is clear. We don’t advocate tolerance, but forbearance with gentleness and enduring harm (2 Tim 2:22-26). This is what we do with other people. Tolerance is a lie as we are called to forbearance. It is the gospel that is at stake.

Now it is our turn where we think about the truth and pass that legacy on. We devote our time to the truth to defend against error.

Inerrancy in Light of the New Testament Writers’ Use of the Old Testament

2015 Shepherd’s Conference Seminar

Notes of Abner Chou lecture from the following source: https://www.gracechurch.org/sermons/10928

Too often, while professors, scholars, and students claim inerrancy of Scripture, they will advocate that it says something else other than Biblical authors intended. Where there is a denial to recognize what Scripture says, they can claim or say anything they want and yet hold on to an inerrantist view or conviction. Scholars and others will deny the historicity of certain events, and the authorship of certain books with excuses always the same. The thought process runs like this: “Inerrancy deals with what the Bible claims” and “I” am saying it claims something else. So whatever you bring up, another person could reject whatever you want because they choose to believe the Bible says something else.

Consequently, through the denial of authorial intent, skeptics can assert that inerrancy becomes meaningless. People begin to claim that the Bible is in contradiction with itself and history while still insisting they are inerrantists. Scholars and skeptics proclaim that inerrancy is dead, and hermeneutics has killed it.

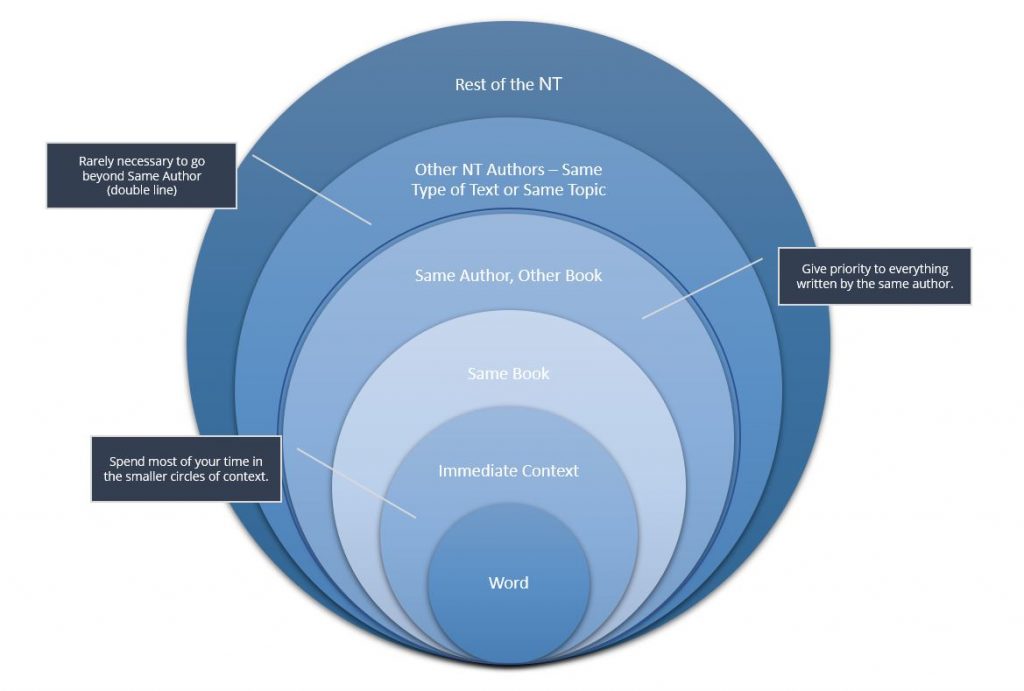

By comparison to this type of thought, the Bible itself informs us about how another Scripture is used to communicate and reinforce meaning. Biblical authors used this intertextuality to apply a hermeneutic to faithful communicate the truth of God’s word. The way biblical writers read Scripture is how they wrote according to a high hermeneutical standard. This is to serve as an example for us today. How prophets and apostles read under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, shows us how we are to rightly divide the Word of Truth. The Bible comes with its hermeneutic included.

The biblical writers are the first inerrantists. To codify the fact that inerrancy is not a recently developed doctrine.

There are three main points about the New Testament’s use of the Old. They are literal, grammatical, and historical. These are points of observation traditionally associated with both inerrancy and hermeneutics. We received these points to identify and describe what is involved in both inerrancy and hermeneutics because that is what the apostles and prophets believed.

The Apostle’s Literal Hermeneutic

A literal hermeneutic is about the interpretation of meaning from an author’s original intent, context, and purpose. In this sense, there is a direct correlation to the issue of truth. Where we can conclude if there is error or mishandling among the apostle’s use of the Old Testament, what they had to say is less than truthful, consistent, or authoritative.

As an example of scholars that dispute the apostle’s literal hermeneutic, consider common assumptions made by Matthew among other New Testament authors. That there is the authoritative weight with Scripture to assure confidence and truth in what is written. With Jesus’s use of “have you not read” in Mt 12:5 and Mt 19:4, He appeals to the use of Scripture as authoritative. He believed Scripture settled issues relevant to readers.

In the New Testament, from Matthew’s (Mt 2:15) use of Hosea (Hos 11:1) in the Old Testament, we see from close examination “what was spoken by the Lord” (NASB). The first exodus referenced in Matthew from our deliverer Christ Jesus is a correlation to the second exodus of Israel written about in Hosea. Whereas we can understand and accept an introductory statement from Matthew that the reference concerns God’s word as authoritative. To support and build context among New Testament writers, biblical writers used the Old Testament to demonstrate meaning and authority and show their confidence in its inerrancy. This occurs numerous times throughout Scripture in various books, chapters, contexts, across genres and authors. Everything is connected.

How the New Testament uses the Old can be illustrated as a chain of reasoning where the prophetic hermeneutic is drawn out and applied by the apostolic hermeneutic. The literal hermeneutic Matthew chose from the book of Hosea factually illustrates a chain of extended authority. As Hosea references the book of Exodus and thereafter, Mathew references Hosea. Whereas, by comparison, Matthew could have appealed to Exodus directly. Scripture interprets Scripture, it is consistent with itself, and it is not contradictory over the centuries. This is a corollary to the doctrine of inerrancy.

The Apostle’s Grammatical Hermeneutic

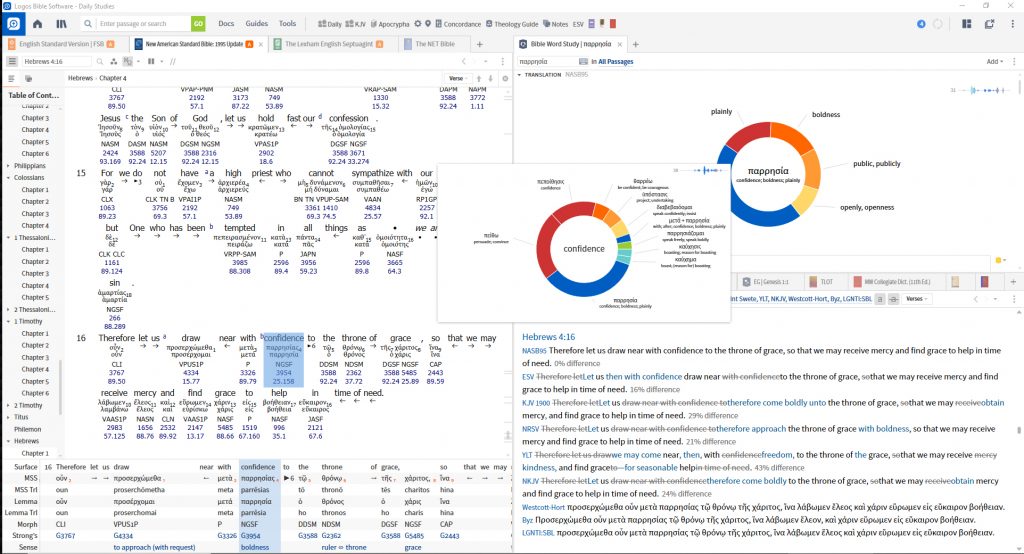

The apostles knew that Scripture is truth word by word in structure and syntax. Disputes among Scholars attempt to show that this is not so as proof texted by Galatians 3:16. Where there is a seemingly errant contradiction between the plural and singular use of seed (NASB) or offspring (ESV). However, with further examination elsewhere in Genesis 22 and Psalm 72, both Abraham and David respectively recognize that there is one promised seed (singular) as again reference in the Galatians 3:16 verse.

Apostle Paul picks up what David references in Psalm 72 to concentrate on the word and grammar of “seed.” Whereas by comparison, modern scholars too often get it wrong. Making use of Galatians 3:16 in isolation without the application of a biblical hermeneutic to grasp a coherent and reliable meaning confirmed as truth.

What Paul refers to in Galatians 3:16 is exceptional evidence of the rule concerning effective sequential linkages in Scripture that correspond compellingly.

The Apostle’s Historical Hermeneutic

Scholars allege that in certain historical narratives, details might never have happened. That certain stories are entirely fictional. Objections to surface with reason about whether or not the apostles viewed historical events within Scripture as truthful and accurate. As evidence, Galatians chapter 4 is relied upon by scholars to make a case of allegory by Paul to show that not even the apostle accepted Scriptural truth within its historical detail.

Since it is demonstrated in Scripture elsewhere and overall that Paul is saturated in historical facts pertaining to numerous events, stories, and covenants across time, we are confident about his use and attention to detail as he writes his letter to the Galatians and even to us today. So Paul’s idea and purpose of allegory are not as we recognize and apply it today. We make sketchy allegorical use of spiritual symbology or principles drawn from Scripture while downplaying history. Paul uses history to make theological points. He argues theology from historical fact to demonstrate it is actualized by it. In 1 Corinthians 15, Paul does the same thing concerning the historical resurrection of Jesus. To say, if you don’t have a historical resurrection, you don’t have a gospel. History is the foundation of theology. In Romans 4:25, the resurrection is necessary for our justification to make again the point that history actualizes theology.

How Paul uses the principle of allegory is demonstrated by what is written in 1 Corinthians 10. Just as Israel was blessed and tempted, we are blessed and tempted. There are these two separate categories from a historical perspective, blessed and tempted. Israel blessed and tempted, the church blessed and tempted as they are categorically the same between both, but allegorical in contrast. Two items grouped and compared in contrast have different categories. So as other authors refer to events or circumstances in Scripture using different categories, by allegory, Paul does the same to connect corresponding theology to historical facts. Not to draw symbolic, vague, or spiritual inferences.

While there is an overall biblical hermeneutic standard, as demonstrated in Scripture, we do not always hit that standard. There is a difference in wrestling with the text as compared to wrestling against the text. We must apply the standard the apostles set for us as much as we can. The Prophetic hermeneutic is the Apostolic hermeneutic, and they, in turn, are the Christian hermeneutic. Inerrancy demands a hermeneutic of surrender as Scripture is the inspired, infallible, and all-sufficient word of God.