Categories Archives: Exegetical

Genesis | Summaries

The Theme of Genesis

The beginning of all things, God originates creation, humanity and the nations.

Summaries

Genesis 1:

God creates the Universe, the solar system, the Earth, humanity, and all living things.

Genesis 2:

God blesses the seventh day, sanctifies it and rests from working. He plants a garden and creates male and female of humanity. God places male and female into the garden to work.

Genesis 3:

God warns about the forbidden tree. Adam (male) and Eve (female) tempted by a deceptive creature. Both succumb to temptation and sinned to thereafter receive God’s curse.

Genesis 4:

Adam and Eve produce offspring Abel and Cain. Cain killed Abel and becomes cursed by God. Cain relocates and bears children with wife. Seth is born of Adam and Eve.

Genesis 5:

Genealogy of Adam to Noah including his offspring, Shem, Ham, and Japheth.

Genesis 6:

Humanity becomes corrupted and God instructs Noah to build an ark. God intends to destroy all flesh.

Genesis 7:

Noah gathers male and female animals to the ark he built. The Earth is flooded, and all flesh perishes.

Genesis 8:

Floodwaters subside then upon the Lord’s instructions; Noah leaves the ark with his family. All the creatures of the Ark also leave. Noah built an altar pleasing to the Lord.

Genesis 9:

The Lord blesses Noah and forms a covenant with him as indicated by the rainbow that forms in the sky.

Genesis 10:

Genealogy from Noah and his sons with their families. Settled is the table of nations.

Genesis 11:

The people of the Earth were united in language and purpose. The Lord confuses their language and disperses them to further regions separate from each other. Descendants of Shem outlined all the way to Abram.

Genesis 12:

Abram sojourns to Egypt. Abram tells his wife to lie on his behalf before Pharaoh in order that he would live. Pharaoh was cursed by God and Sarai was returned to Abram.

Genesis 13:

Abram and Lot separated with distributed land and livestock among them. The Lord promises Abram the blessings of descendants and territory.

Genesis 14:

The kings of the regions were at war. Lot was captured and rescued by Abram and his forces. King Melchizedek blesses Abram and the Lord. King of Sodom offers provisions to Abram.

Genesis 15:

Abram promised a son. The Lord makes a covenant promise to Abram about extending territory for his descendants.

Genesis 16:

Sarai has the Egyptian maid Hagar marry Abram and bear children with him. Hagar despised Sarai and a rivalry developed with Hagar’s removal from the people. The Angel of the Lord promises descendants to Hagar. Ishmael is born to Hagar and Abram.

Genesis 17:

Abram was renamed Abraham and the Lord’s covenant with him is reinforced. A sign of the covenant through circumcision is established with the newborn of the people.

Genesis 18:

The Lord promises to Abraham a son and reveals to him the forthcoming destruction of cities Sodom and Gomorrah. Abraham appeals to the Lord about the righteous people among the wicked in both cities.

Genesis 19:

The Lord rescues Lot and thereafter destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah. Lot was violated by his daughters. They gave birth to the predecessors of the Moabite and Ammonite people.

Genesis 20:

Abraham again used Sarah’s status as his sister to protect himself from harm. King Abimelech warned by God to return Sarah to Abraham or he will be killed. Sarah was returned to Abraham.

Genesis 21:

Abraham’s son Isaac was born to Sarah as the Lord promised. Sarah’s displeasure with Hagar from Egypt caused Abraham to send her away. The Lord promised a great nation of Ishmael, Hagar’s son.

Genesis 22:

The Lord tested Abraham with His command to offer a sacrifice of his son Isaac. Abraham’s love and obedience for the Lord demonstrated the willing sacrifice of his son. The Angel of the Lord stops Abraham from slaying his son and He blesses him.

Genesis 23:

Sarah died and was buried in a cave at Machpelah.

Genesis 24:

A bride for Isaac was identified and chosen at a spring and well near Nahor in Mesopotamia. Isaac marries Rebekah.

Genesis 25:

Abraham died as he was buried in a cave at Machpelah. The rivalry between Jacob and Esau emerges, and Esau sells his birthright to Jacob for a meal.

Genesis 26:

Isaac takes up residence in Gerar where he has a quarrel with herdsmen over water wells. Abimelech from chapter 20 makes a covenant of peace with Isaac.

Genesis 27:

Isaac and his mother Rebekah deceived Jacob to steal his blessing from first-born Esau.

Genesis 28:

Jacob sent away to Paddan-aram to seek a wife. Jacob has a dream about a ladder reaching into heaven with angels ascending and descending upon it. God appears before Jacob with a promise of territory for his descendants.

Genesis 29:

Jacob meets Rachel and works for Laban to earn her hand in marriage. Laban tricks Jacob to cause him to marry Leah. Jacob works extra duration to finally marry Rachel.

Genesis 30:

Jacob bears children with Leah. God opens the womb of Rachel in that she is able to bear Joseph. Jacob prospers through his earnings and status with Laban.

Genesis 31:

Jacob leaves Laban and heads to Canaan under the instruction of the Lord. Laban pursues but is met with a warning from God not to speak against Jacob. Laban and Jacob make a covenant of peace.

Genesis 32:

Jacob encounters news from his messengers about Esau’s forthcoming meeting with him. Jacob becomes fearful and prays to the Lord for protection. Jacob wrestled with God for a blessing.

Genesis 33:

Esau reaches Jacob and he is delighted to see his brother and family. Jacob declines to travel further with Esau. Jacob settled in Shechem.

Genesis 34:

Shechem, the son of Hamor, raped Jacob’s daughter Dinah. As a result, Jacob’s sons, Simeon and Levi, killed the males of the city. Along with Hamor and his sons, including Shechem.

Genesis 35:

Jacob relocates to Bethel upon the Lord’s instructions. Jacob is renamed Israel and the 12-tribes of Israel are identified.

Genesis 36:

The genealogy and descendants of Esau are listed by name and location.

Genesis 37:

Jacob’s son Joseph dreams of his reign over his brothers. His brothers plot against him where he is sold into slavery.

Genesis 38:

Judah neglects Tamar and doesn’t present Shelah his son to her as a mate. Judah unknowingly mates with Tamar thinking she was a prostitute. Tamar bears Judah’s twin sons, Perez and Zerah.

Genesis 39:

Joseph escapes Potiphar’s seductive wife and gains success at the Pharaoh’s household in Egypt. Joseph is imprisoned after being falsely accused by Potiphar’s wife.

Genesis 40:

Joseph interprets Pharaoh’s dream to the chief cupbearer about the demise of the chief baker.

Genesis 41:

Joseph interprets Pharaoh’s dream and he is made a ruler of Egypt. Joseph bears two sons, Manasseh and Ephraim.

Genesis 42:

Joseph’s brothers go to Egypt to buy grain and eventually appear before him. Simeon is held bound in Egypt while Joseph’s brothers were to return to him with Benjamin the youngest.

Genesis 43:

Joseph’s

brothers return to Egypt with Benjamin. Joseph is delighted by seeing them,

seeing Benjamin, and hearing about Jacob’s well-being.

Genesis 44:

Joseph’s brothers are brought back to Egypt after it was previously discovered that Benjamin had falsely stolen silver/goods in his sack.

Genesis 45:

Joseph is reconciled to his brothers. He has an entire family, including Jacob, who is given a place to stay in Egypt due to the forthcoming famine.

Genesis 46:

The Lord appears to Jacob in a dream to give him confidence about going to Egypt. The families of Jacob who relocate to Egypt are listed by name.

Genesis 47:

Jacob and his family settle in Goshen with pledges of support from Pharaoh. Jacob gets Joseph to promise his forthcoming burial with their forefathers.

Genesis 48:

Just prior to Jacob’s death, he blesses Ephraim and Manasseh. Jacob tells Joseph that God is with him and will return him to the land of his fathers.

Genesis 49:

Jacob gathers his sons and prophesies about their forthcoming days ahead. All the heads of the tribes of Israel are separately blessed. Jacob dies.

Genesis 50:

Jacob is mourned, and Joseph buries him at Machpelah as promised. Joseph dies at 110 years old with his remains interred in Egypt.

False Prophets & Teachers | 2 Pet 2:1-22

In obedience to the great commission, the formative Church in Asia Minor was developing through missions, evangelism, and discipleship. As people recently in the faith of our Lord Jesus, there were numerous people in the region susceptible to predatory false teachers who were steeped in the culture of the time. Heavily influenced by Greco-Roman philosophical thought, people were thoroughly committed to self-indulgence and all forms of personal interest centered on pleasure, consumption, and sensuality. Whether intentional or unintentional among people who sought to corrupt people within the Church, the reach of harmful influences and outright instruction they advocated was harmful and damaging. Subtle intruders who cause significant error by false ideas contradictory to the truth of Scripture are called out by Peter. With specifics about who they were by their behavioral attributes.

“Forsaking the right way, they have gone astray. They have followed the way of Balaam, the son of Beor, who loved gain from wrongdoing…”

– 2 Peter 2:15

Authenticity, Canon, Dating, & Purpose

The Epistle of 2 Peter was a contested book of the Bible as it was not recognized in the canon among some early Church manuscripts. Some Church fathers also dismissed its status as having divinely inspired authority. From scholars centuries ago, to professional academics today, the authorship, date of writing, literary style, and content is disputed as authentically from Peter, an Apostle of Christ. To call into doubt its origin and the substance of its message. Early Church historian Eusebius once wrote, “Of Peter, one epistle, named as his First, is accepted, and the early Fathers used this as undisputed in their own writings. But the so-called Second epistle [of Peter] we have not regarded as canonical, yet many have thought it useful and have studied it with the other Scriptures.”1 While Eusebius of Caesarea was of the 4th century, much later Guerike acknowledged its authenticity within the external testimonies. 2 Where the second epistle was ecclesiastically acknowledged as part of the Canon during the 4th century.3 From Jerome to Origen, Clement of Alexandria, Justin, Irenœus, Theophilus of Antioch, Hermas, Barnabas, and finally to Dietlein (1851), with whom its authenticity was proven from before the destruction of the second temple. The Church ultimately accepted the epistle within the Canon of Scripture with its authenticity recognized by the end of the fourth century.

During the Apostolic period between Paul’s ministry to John’s writing of the apocalyptic book of Revelation, it is recognized that Peter wrote his second letter to the Church in Asia minor. Just prior to his death in about A.D. 65, Peter’s letter is dated after Paul’s letters were written to the Church. Likely after the completion of Paul’s and his ministry and travels. Scholars who dismiss the authenticity of Peter’s epistle, date the letter to about the second century.

Delivery, Literary Style, and Audience

Structurally, the letter is in a chiastic form of literary delivery. There is a synchronous and coherent form of meaning that contributes to the letter’s overall purpose. While there is some uncertainty among scholars about the epistle’s intended audience during the approximated time of writing, the substance and relevance of Peter’s message are directed to the Church in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). For centuries thereafter, the letter has been contemplated, studied, and applied rigorously by Godly people who love the Lord and remained committed to His word as Scripture. For generations to follow, the first epistle of Peter becomes recognized as having exhortations and warnings from people external to the Church, while the second epistle concerns warnings about false teachers internal to the Church. From Gentiles to authorities, masters, spouses, members of the Church body, Peter urges his readers to honor God in their conduct. Later, in his second epistle, Peter warned about false teachers who secretly destructive heresies into the body of believers (2 Pet. 2:1).

Peter’s message concerning false teachers corresponds to Scriptural texts across genres and authors. Namely, the book of Jude is another well-known written work concerning false teachers. In fact, much of its substance corresponds to the core of overall warnings read within Peter’s letter. Church members susceptible to false instruction about principles of their faith were exposed to harmful ideas and practices that ran contrary to the teachings of Christ himself as often delivered by His Apostles. Condemnation and warnings from Jeremiah (Jer. 23:9), John (2 Jn. 7), to Paul (Rm. 16:17-18), and others also indicate a widespread presence of false teachers and false prophets over long periods of time. One might conclude there began a continuing presence of this spirit of deception behind pagan and gnostic thought. With repeated and continuing patterns of deception with the typical layers of idolatry accompanied by untruthful, heretical, and immoral practices, the “doctrines of demons” (1 Tim 4:1 NKJV) remain sustained across humanity. Throughout Peter’s second epistle, there are numerous past and present-tense participles that indicate an active and historical nature of teaching false principles within the early Church. The specifics were not articulated about what false teachings were occurring, but the inevitable outcomes attributed to those propagating ideas and nonsense centered around personal gain and error were marked by a licentious lifestyle common during that period. For example, within chapter two concerning the rise of false teachers and rebellion, to express causes and consequences, a reader sees terms such as “denying” (2:1), “daring” (2:10), “reviling” (2:12), “maligned” (2:2), “condemned”, “reducing” (2:6), and “oppressed” (2:7) as ideas and various others to reveal corrupt thought and historically condemned activity. Taken together, these terms constituted a sense of harmful disruption alarming to Peter. Where there was a clear Epicurean worldview threat of division as compared to historical and Scriptural truth about our Lord, who He is, what He has done, and what He is doing as revealed among the authentic apostles and prophets.

Background, Historical Perspectives

During the time of Peter’s letter to the Church in Asia Minor, Gentiles were immersed in secular culture involving trade, social gatherings, protests, travel, paying taxes, court cases, work, and daily family life. The various geographic areas within the territory of Asia Minor are well known throughout the New Testament. Specifically, within the Gospels, Acts, the Epistles, and the prophetic work of Revelation. The cities and towns throughout Asia minor surround the Mediterranean Sea with numerous references to their significance throughout the Bible in the New Testament. As a springboard of the Church beyond Israel, the great commission going forward among the Gentiles extended beyond the Jewish people as planned throughout redemptive history.

As the area was thoroughly influenced by the adjacent nations of Greece and Italy, the people were steeped in Greco-Roman culture during the time.4 The larger ancient world of Gentiles was distributed throughout the developing world, beginning in Rome and Athens continuing Westward. A growing Christendom heading into Europa with the early Church was sovereignly and geographically positioned to flood the Earth with the gospel. Even with the corrupt beliefs and practices of idolatry involving false pagan gods, and the cultural focus on self-pleasure attributed to society within Greece, the Church was incubating with impurities affecting its overall health and purpose. Whether by Roman gods or Greek gods, the spiritual condition of people throughout the area was infected by self-deception likely reinforced by cultural and societal pressures. Not to mention supernatural forces of darkness, the Apostle writes to the Church in Ephesus about (Eph. 6:12).

Social, Cultural, and Philosophical Influences

The historical onset of Gnosticism appears to have placed undue pressures upon the early Church and Christ’s ministry through His Apostles. Gnosticism at the time was recognized as a collection of teachings as they represented a combination of ideas taken from mysticism, Greek philosophy, and Christianity. In contrast, the justification was achieved through knowledge (the Greek word for “knowledge” is gnosis) and not by faith, as articulated by Paul in his letter to the Ephesian church (Eph 2:8-9). To understand the adverse effects of Gnostics at the time, a careful look at their cultural practices and chosen lifestyles gives an in-reverse look at the root of those influencing believers at the time of Peter’s letter (and that of Jude). From about the second century, looking backward, there is sufficient explanation about the errors in conduct that came about to contradict our Lord’s instructions to the Church through Peter. With cultural influences of philosophical thought from Roman paganism to later growing Gnosticism, as the source of false teaching alluded to by its pernicious outcomes and inevitable lifestyles by those who fall away from the faith.

Not only were the egregious lifestyles of Gnostic influence upon formative Christendom alarming to Peter, but their false systems of belief were setting in. It was entirely necessary to call out the heretical and sinful problems that were occurring. Within the congregations in Asia Minor, they were to understand that both subtle and overt contradictions were upon them, and it was necessary to recognize the errors, reject false teachings, and uphold Truth. The outcomes explicitly contradictory to Scripture and apostolic instructions for the Church were evidence of the types of erroneous beliefs upon them at the time.

In Scripture, the coming of the false teachers was predicted (Acts 20:29, 1 Tim. 4:1, 2 Tim. 3:2) with their worldview firmly systemic as Epicurean and Antinomian. Hostile to Christ, they were as fierce wolves, deceitful, disloyal, committed to doctrines of demons, lovers of self, proud, arrogant, abusive, disobedient to their parents, ungrateful, unholy, heartless, unappeasable, slanderous, without self-control, brutal, not loving good, treacherous, reckless, swollen with conceit, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God. Having an appearance of godliness but denying its power (2 Tim. 3:2-5). The worldview of Epicureanism, as originated by Greek philosopher Epicurus around 300 BC, was characterized by a philosophy of pleasure. They were living for the flesh through a means of carnality involving a delight in physical appetites such as sensuality, passions, material satisfaction, and sexual pursuit. It was and is a form of hedonism. A form of antinomianism also accompanied Epicureanism at the time of Peter’s warning. A term which originates from the Greek ἀντί (anti “against”) and νόμος (nomos “law”). Whereas Gnostics were against religious or spiritual influences upon the lives of their adherents. Particularly concerning the Mosaic law and early Christianity (i.e., “living by the Spirit”). Scriptural teaching from the Prophets and Apostles was therefore rejected by some within Hellenistic society, which identified with an Epicurean and Antinomian worldview developing at the time. With a backdrop of historical paganism and Roman influences during the first and second centuries, Peter’s warnings against people who teach from a foundation of these assertions and premises were charged as false and summarily required full rejection. Not only of the ideas and principles but of the people themselves who carried them and somewhat occupied the Church (2 Tim 3:1-5).

Content Analysis and Genre

Peter’s second letter to the churches in Asia Minor was likely circulated. To provide instruction, guidance, hope, and warnings concerning the erroneous philosophical worldview that has made its way among congregations. This was a form of correspondence that carried significant weight as members of the body of Christ were attentive to its meaning. Specifically, concerning the harm brought to individuals that accept instructions and beliefs contrary to their training, time with the leaders of the Church, and the Scriptures. While the Holy Spirit at the time was active in the Church, individuals deceived and given over to the lifestyle characteristics of false teachers were susceptible to highly destructive outcomes. Notwithstanding the intentions of God’s sovereign will, there were genuine impediments to the promises of the Lord imperiled. The growth of the churches at risk of becoming stunted with their effectiveness diluted in terms of discipleship and furtherance of the gospel.

The literary parallels between 2 Peter and Jude are apparent to the casual reader of these two epistles.5 Particularly among those who desire to make passage-by-passage comparisons.6 The following table of comparisons is assembled to highlight the commonality between the two authors of Scripture to reinforce the warnings to the Church during the first century. These two letters placed side by side correspond to separate yet interrelated meanings. Taken together, it is easy to see commonly translated verbiage. So, there is substantial speculation among historical and modern Biblical scholars about their sources.

About one letter borrowing from another, an amanuensis relationship between authors, yet there is no actual proof or historical certainty about the nature of their relationship to one another.7As presented earlier, both letters are intended for readership throughout Asia Minor. This is the broader context of churches identified by geographical names in Scripture. The same locations Apostle Paul wrote about and among those to Galatia, Colossae, Philippi, and Thessalonica. A little further to the West in Rome and throughout the islands off the coast of Greece. It is in this area that New Testament authors wrote to the early churches concerning many ecclesiastical and theological matters of interest. Moreover, Paul’s letters to the Galatians indicate a common moral decay of social and cultural conditions among the population who influenced false teachers that Peter and others wrote about.8 As an underlying body of corruption, Paul’s “works of the flesh” (Gal. 5:19) correspond to the types of depravity, Peter wrote about to the churches in Asia minor.

| 2 PETER | JUDE | PASSAGE |

|---|---|---|

| 2:1 | 4 | Denial of the "Sovereign Lord" |

| 2:3 | 4 | False teachers' "condemnation" from the past |

| 2:4 | 6 | Angels confined for judgment |

| 2:6 | 7 | Sodom and Gomorrah as examples of judgment of gross evil |

| 2:10 | 8 | Rejected or Despised Authority. |

| 2:11 | 9 | The angel Michael did not condemn for slander, or angels did not heap abuse. |

| 2:13 | 12 | False teachers are blemishes. |

| 2:17 | 12 | Clouds without rain, blown along by the wind. |

| 3:3 | 18 | Ungodly desires or "scoffers" following their own evil. |

| Table 1. – Literary affinities between 2 Peter and Jude |

Exegetical and Critical Review

The destructive nature of false doctrines within the Church is explicitly narrated at the outset of chapter two, whereas there is a distinction made between false prophets and false teachers. Specifically, a difference in the method of introduction concerning destructive ideas, concepts, and principles. One could surmise that the heretical teachings introduced were incremental, subtle, and persistent. With the compelling character of interpersonal influence among heretics, they were becoming seductive while appealing to the nature of common people growing in their faith. Namely, false teachers blaspheme the way of the truth (2 Pet. 2:2 NASB) with persistence (2 Pet. 2:2 NASB). The motivation of such efforts is detectable through a covetousness or greed corresponding to the motives of culture and society at the time. As Peter warned, their ruin is inevitable along with those who follow their teachings contrary to Scripture and their development shepherded by the Lord through the Apostles (2 Pet. 2:1-3 NASB).

Compared to the judgments that befell the people of ancient Israel, the fate of false teachers was assuredly common. As written by Peter to recount prior calamities that devasted and doomed the rebellious and wicked enemies of truth. This reminder in Peter’s letter is not arbitrary but fitting to the types of conduct coming from people who were quietly bringing destructive heresies into the Church. The angels who sinned (1 Enoch 15:1-12), the ancient population of the world at the time of Noah (Gen. 6:11-13), and the people of Sodom and Gomorrah (Gen. 19:13) were explicitly characterized as people to brought judgment upon themselves because of their specific sins common to the false teachers Peter warns about. False teachers among those within the Church were described as those who possessed “eyes full of adultery” who “cannot cease from sinning and entice unstable souls.” Likely Gnostics who held an Epicurean worldview and lived according to the flesh, they were covetous for the people within the early Church to fulfill their sensual desires.

Specifically identified as people who seek to corrupt the truth by deception to gain further pleasure and satisfy short-term desires. They were people who “indulge the lust of defiling passion and despise authority (2 Pet. 2:10).” Some became people in the church unable to stop sinning as having an insatiable appetite for physical pleasure. Familiar with what Paul wrote about the churches, Peter goes somewhat further to indicate a criterion by which people today can detect, recognize, and counter teaching that surfaces from the same or similar root causes. Namely, materialism, self-indulgence for personal gain, and numerous additional characteristics identified by Peter, Paul, Jude, and others.

The lifestyles of people who are in the Church today are very much relevant to their roles involving teaching, counseling, preaching, discipleship, and even general fellowship in a leadership or mentoring capacity. If in an uninhibited way, people in the Church are living as described by Peter in his letter (2 Pet. 2:18-22), these Scriptural attributes are an indicator that a pattern of false or corrupted influences can make their way into congregations, or the hearts and minds of individuals. They were causing further error to deepen corruption and a polluted walk with Christ and fellowship with others. It is within Peter’s second letter that today we can identify from a collection of meaningful attributes to understand where there are risks involving unbiblical conduct to place a spotlight upon false teaching. In an effort to expose what separation exists between our Lord’s cardinal expectations and the entanglements of sin. Moreover, this condition appears punctuated by the harmful lifestyles recognized among those who profess a sincere relationship and commitment with Christ but refuse to abide by what He requires of His followers (Matt 5:21-45).

As interpersonal relationships are formed among people within congregations, or even by the social conduct of people within Christendom as a whole, we can begin to understand how or where there are heretical teachings, or at minimum social ideas and principles that run contrary to the objective truth of Scripture. For example, one could encounter outright unbiblical opinions and proposals within a local church. Conversely, within social media, or among Progressive Christian circles, there are more substantial theological and philosophical challenges that emerge as a historical backdrop. From the first-century period of the church throughout Asia Minor—where the “Way of Balaam” (2 Pet. 2:15) becomes held out as a higher standard because of the pursuit of personal self-interest and gain.9 Rather than to seek the well-being of others, love them, and the Lord to honor what conduct, learning, and commitment to the truth He expects of us.

With numerous perspectives, opinions, and educational backgrounds among people in society today, there is a critical need for those in Christ to search for truth and understand it according to Scripture. This effort requires a commitment to the Biblical principles that withstand cultural pressures, especially within the Church. Across all denominations, confessions of faith, academic institutions, and local fellowships, there must be a developed and sustained effort to comprehend and accept the truth of Scripture according to what is intended by its authors. Truth that is not according to subjective preferences or interpretations as an effort to force an outcome outside what the Lord has decreed and revealed by His grace. Too often there are leaders and individuals who are not grounded well enough to instruct and guide others in the truth, much less their own personal spiritual walk. 10

To highlight explicit lifestyle attributes among false teachers, we can refer to an outline of their underlying conduct and spiritual condition. Where there is smoke, there is fire so if this becomes a severe problem in terms of Scriptural and theological subject matter, we have Biblical guidelines To highlight explicit lifestyle attributes among false teachers, we can refer to an outline of their underlying conduct and spiritual condition. Where there is smoke, there is fire so if this becomes a severe problem in terms of Scriptural and theological subject matter, we have Biblical guidelines11 to give reference to Table 2 as we seek safety in the truth of Scripture. To safeguard the Spiritual well-being of we and others to preserve truth among all followers of Christ. to give referrals to in Table 2 as we seek safety in the truth of Scripture. To safeguard the Spiritual well-being of us and others to preserve truth among all followers of Christ.

Outline of Underlying Conduct Among False Teachers in 2 Peter:

| VERSE | KEY TERM(S) | MODES OF BEHAVIOR (FRUIT) |

|---|---|---|

| 2:1 | ἀρνέομαι δεσπότης (aparneomai despotēs) | Denial of the Lord. - Who purchased or acquired them through His atonement. |

| 2:2 | ἀσέλγεια (aselgeia) | Indulges in sensual pleasures. - Unrestrained by convention or morality. Licentiousness. |

| 2:2 | ἀλήθεια βλασφημέω (alētheia blasphēmeomai) | Slanders and dishonors of sacred truth. |

| 2:3 | πλεονεξία (pleonexia) | Possesses an excessive desire of acquiring more and more (wealth). |

| 2:3 | ἐμπορεύομαι πλαστός λόγος (emporeuomai plastos logos) | Using false words, deprives others of something valued by their deceit. |

| 2:10 | σάρξ πορεύομαι (sarx poreuomai) | Walk and live in a physical appetite for lust of the flesh. |

| 2:10 | ἐπιθυμία μιασμός (epithymia miasmos) | Possesses an inordinate, self-indulgent evil craving that displaces proper affections for God. |

| 2:10 | καταφρονέω κυριότης (kataphroneō kyriotēs) | Looks down upon authority with contempt. |

| 2:10 | τολμητής αὐθάδης (tolmētēs authadēs) | Improperly forward, presumptuous, or bold. |

| 2:10 | αὐθάδης βλασφημέω (authadēs blasphēmeō) | They are self-important or primarily concerned about one's own interests without fear. |

| 2:13 | ἐντρυφάω ἀπάτη (entryphaō apatē) | Reveling to cause others to believe untruth. |

| 2:14 | μοιχαλίς δελεάζω ἀστήρικτος ψυχή (moichalis deleazō astēriktos psychē) | They continuously perceive people as objects of adultery against the truth of God. |

| 2:15 | ἀγαπάω μισθός ἀδικία (agapaō misthos adikia) | They follow the way of Balaam, where their "prophecy" is used to legitimize their claims of authority. An exploitation of "prophecy," or the "prophetic word" to override the truth of Scripture and valid apostolic teaching from original and direct Apostles. Loves unjust gain from wrongdoing. |

| Table 2. – Underlying Conduct of False Teachers |

Conclusions

Even with historical and contemporary contention among scholars about the origin and authenticity of 2 Peter, it is today an accepted apostolic epistle within the canon of Scripture. It is inspired and inerrant as a contribution to the all-sufficient word of God. The content and style of writing that occurred corresponded to the inspired material produced by Apostle Paul, Jude, and others as well. While Peter’s letters were unique to him as an eyewitness to Messianic events that occurred, the authenticity of his overall work is recognized and lived out by those faithful to the truth of Scripture.

A core and significant value of Peter’s letter concerns were warnings about false teachers. As the early Church grew throughout Asia Minor, there were cultural philosophies emergent within society that brought about underlying and corrupt behaviors. As provident throughout early Christendom, the Lord’s work through Peter’s second letter gave clear specifics about how to detect false teaching through the conduct of people who were in error, or altogether defiant while condemned for their betrayal of the truth, rejection of Scripture, and defiance of apostolic instruction.

Citations

___________________

1. Eusebius, “The Church History: A New Translation with Commentary,” 93.

2. Guerike, “Gesammtgeschichte des Neuen Testaments,” p. 477. 615.

3. Lange, “A Commentary of the Holy Scriptures: 2 Peter,” Genuineness of the Epistle, Logos Systems.

4. Jones, “The Cities of the Eastern Roman Province” 28-95.

5. Elwell, Yarbrough, “Encountering the New Testament,” 366.

6. Carson, Moo, “An Introduction to the New Testament,” 655-656.

7. Ibid., Carson, Moo, 655-656.

8. Sproul, “Ligonier Study Bible,” 1820.

9. Hunt, “The Way of Balaam,” 1995, accessed March 08, 2020, www.thebereancall.org/content/way-balaam.

10. MacArthur, “The Gospel According to Jesus,” 127-131.

11. Lockman Foundation, “Greek Dictionary of the New American Standard Exhaustive Concordance”

Bibliography

Guericke, Heinrich Ernst Ferdinand. Gesammtgeschichte des Neuen Testaments. n.d.

Hunt, Dave. The Berean Call. September 1, 1995. https://www.thebereancall.org/content/way-balaam (accessed March 08, 2020).

Jones, A. H. M. The Cities of the Eastern Roman Province. Pliny: Oxford University Press, 1937.

Lange, John Peter, Phillip Schaff, G.F.C. Fronmüller, and J. Isidor Mombert. A Commentary of the Holy Scriptures: 2 Peter. n.d.

MacArthur, John. The Gospel According to Jesus. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008.

Mounce, Robert H. A Living Hope: A Commentary on 1 and 2 Peter. Eugene: Eerdmans Publishing, 1982.

Pamphili, Eusebius. Eusebius – The Church History: A New Translation with Commentary. Translated by Paul L. Maier. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1999.

Sproul, R.C. The Reformation Study Bible. Lake Mary: Ligonier Ministries, 2005.

The Lockman Foundation. Greek Dictionary of the New American Standard Exhaustive Concordance. La Habra, 1998.

Walter A. Elwell, Robert W. Yarbrough. Encountering the New Testament. A Historical and Theological Survey. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1997.

The Canonicity of Scripture

This work seeks to cover a range of topics concerning the canon of Scripture. From historical to contemporary perspectives to get an in-depth look at both the Old and New Testament formation, which together as a whole constitute the whole canon of God’s eternal word. During the research for this project, a significant number of factors were examined at length to grasp the weight and concentration of activity and inspiration that went into the assembly of the Bible down through the centuries. The origination, delivery, and assembly of the Bible are placed into our hands today by providence from our all-merciful Lord and King. We have a debt of eternal gratitude for its place in our lives.

Outline

A.) Introduction

B.) Old Testament Canon

– 1.) Historical Development

– 2.) Genre & Formation

– 3.) Criticisms, Responses, & Implications

C.) New Testament Canon

– 1.) Historical Development

– 2.) Genre & Formation

– 3.) Criticisms, Responses, & Implications

D.) Conclusions

E.) Bibliography

A.) Introduction

Today, the Holy Bible is reportedly the best-selling book in the world.1 With its deep and lasting influence upon individuals, society, governments, and institutions; it reaches deep into our common realm of existence to have an everlasting impact upon conduct, policy, culture, law, lifestyles, art, sciences, and everyday living. The word of God is venerable and represents a class of literary work of its own. Extending back for thousands of years, with the events of mankind upon the Earth, it has recorded the activity of creation and humanity to such an extent that it shapes the thinking and worldview of billions among both the living and the dead.

The weight and substance of Scripture’s authority are somewhat supported by its canonization. Through sovereign orchestration and ordained use of God’s word read publicly and privately, the selection of communicated texts was produced and distributed for the development and well-being of the Church throughout Christendom. As written, collected, and meticulously reproduced over thousands of years, a formative process to codify recognition, understanding, and acceptance of divinely inspired writings came about to shape what is today defined as the canon of Scripture. More specifically, the canon is the “list of all the books that belong in the Bible.”2 Etymologically speaking, the term canon originates from the Greek word “kanōn” (κανών), which is translated as “rule” or “measuring stick” among other common terms as a way to size, quantify, or gauge dimensions of truth. This word is likely a derivative of the Hebrew term “kaneh” which means “reed’. To also mean from the Latin, the canon is the source of absolute divine authority in the lives of both Jew and Gentiles or peoples of the Earth for all time.

When God breathed out His word over a period of time, they were recorded through a series of events concerning His plan to restore creation throughout redemptive history. Both literally and theologically, the canon of Scripture gains acceptance in meaning through the recognition of root-word definitions over time and canonical discovery among Church fathers. Ultimately, God determines canonicity.3 Whereas canonization refers to the method by which sacred texts are brought together by their usage and authority.

The process of canonization involves recognizing what was always canonical. Where there is a canonical consciousness in Scripture, ecumenical fathers and councils come to recognize its authority and divine inspiration while in use among church gatherings. Scripture itself correlates to what is true from among its various separate authors. At a macro level, the entire body of Scripture is systematic and fixed as a single entity. It is not to be tampered with, appended, or redacted. From Deuteronomy to Malachi in the Old Testament, there is an expectation about a forthcoming prophet woven together in the text across various genres.

For example, the Pentateuch of Scripture is together sealed as a cohesive unit prior to covenants becoming the redemptive backstory of history. Long before the new covenant was developed and communicated in the New Testament, the formation of the Old Testament canon was recognized by the prophets and people throughout the centuries as having authority. It was self-declarative then as God’s word with support extending throughout the remaining Old Testament over time and all the way through the New Testament to communicate the new covenant and the work of Jesus, His apostles, and the early church. From beginning to end, the revelation of God was recorded throughout the New Testament, just as it was in the Old Testament.

God spoke through Scripture from Revelation all the way back to Genesis. As the prophetic activity began in Deuteronomy and extended throughout the Old Testament among major and minor prophets, the fulfillment of those prophesies come about with new prophetic meaning is formed through revelation as articulated in the book of the Apocalypse, or the book of Revelation. This range of revelation communicates God’s intent through His prophets and apostles to demonstrate the interwoven nature of Scriptural messaging. Where together they are spiritually and canonically synchronous and guided by providence to reach us today.

The interconnected nature of the Old and New Testaments are an eternal witness to the canonicity of Scripture. As God spoke to through the apostles and prophets, they wrote and spoke what was revealed to them, the early church, and to us today. The cascading effect of reference among both Old and New Testament writers gives extraordinary weight to the authenticity of God’s word. There is the credibility of appointed and ordained people sequentially building upon one another to thread together coherent spiritual and supernatural meaning for generations. It is without uncertainty that Scripture consists of these canonical seams4 to further reinforce its total authority as intended.

The canon of Scripture is not a passive expression of interconnected texts. It is a binding testimony recognized by Church history concerning the revelation of God through the prophets and writings of the apostles. While the canonization process throughout history was messy, it has a formative background across large geographical distances, across large spans of time, and across human languages. The authority of Scripture, as supported by its canonical status, transcends scrutiny to withstand social and cultural pressures across the same stretches of time, geography, and language. The Bible itself declares its canonicity, and as a living entity, without being sentient, it is self-aware.

B.) Old Testament Canon

There are three Old Testament categories that are contained in the Bible that have a bearing on their formation and thereafter recognition within the Church. Within the Bible, the first books of the law include Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Known as the Torah, or Pentateuch these are the beginning books of the Bible. Following the books of the law, there are thirteen total historical books of the Bible to include Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 Samuel, 2 Samuel, 1 Kings, 2 Kings, 1 Chronicles, 2 Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther. There are additional apocryphal non-canonical books of history, including 1 and 2 Esdras, Tobit, and Judith. Continuing through the Bible after the books of the law, and historical writings, there are five books of wisdom and poetry. Namely, Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon. Finally, the books of the Bible are separated in notoriety, and substantive impact as Major and Minor prophets are a total of seven and twelve, respectively. The seven books of the Minor Prophets are Hosea, Amos, Micah, Joel, Obadiah, Jonah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. The five books of the Major Prophets are Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Lamentations, and Daniel. All of these books of the Bible listed here are their English language renderings by name or title.

The historical development of the Old Testament canon involved three operative principles as a matter of process. They are inspiration, recognition, and preservation. Together these principles concern the three steps of placement and delivery of the total canon of Scripture. Among all 39 books of the Old Testament, they were first introduced by God so as to exclude other writings that were not inspired. These are the closed canon of the Old Testament as progressively revealed and inspired truth originating from God. The recognition of revealed and inspired truth that became transmitted and circulated were thereafter preserved as a collection of interconnected writings on ancient media originating from the oral tradition and copied from texts produced by Old Testament authors.

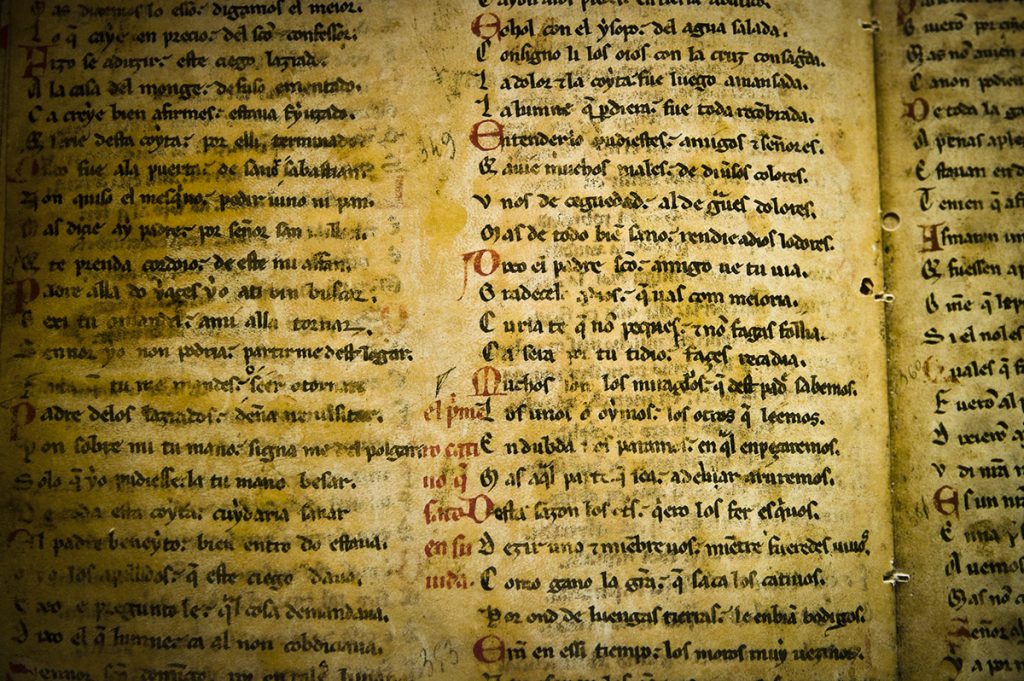

1.) Historical Developments

There is separate historicity to each area of Scripture. Specifically, concerning the books of the law, the prophets, and other writings. While it is recognized that the Antilegomena5 pertains to disputed New Testament books, there were contested books of the Old Testament also. Historical attestation of the Hebrew canon extends back to numerous influential people involved in church leadership, translation, textual analysis, and ecumenical policy. Also known as the Masoretic canon, the Hebrew bible was largely compartmentalized as separate books that were recognized as having informational validity, but it was necessary to recognize those which were divinely inspired. Through a lineage of lists, authors, and historians, Jewish people of long ago held a tripartite view of canonical Scripture as a total homogenous effort. The Masoretic Text canon was unquestionably accepted and used as the early Bible or the Holy Scriptures among the ancient Hebrew people. The books of the law, the books of the prophets, and “the writings” together were a composite of inspired Scripture as cataloged throughout the ages. “The Writings” classified in the Masoretic Text as the Kethûbîm (or Ketuvim) were also referred to as the “Hagiographa.”6 This is termed to represent all books of the Hebrew Scriptures after the Torah along with the major and minor Prophets comparatively interspersed chronologically. They were historically brought into the final third of the Old Testament who were among those, who followed the steps of the prophets. All three major divisions became widely set adjacent from Genesis to Malachi among influential people to include Josephus, Melito of Sardis, Origen, Eusebius, Tertullian, and Jerome.

It was Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian who concluded that after the closure of Malachi, the last book of the Old Testament, there were no further prophetic books from about 424 B.C. that communicated revelation from God to the Jewish people. Therefore, while there was yet chronological prophetic activity, there was no further way to substantiate or safely conclude other writings outside the Masoretic canon to confirm they were authentic or even divinely inspired. The books listed by Bishop Melito of Sardis in A.D. 170 account for the earliest listing of all Old Testament books except for a few that were later recognized, among others. Nearly one hundred years later, Origen in the third century A.D. recognized the same 22 canonical books as Josephus. Even Hilary of Poitiers and Jerome recognized the 22 canonical books, whereas for hundreds of years after about 425 B.C., the Old Testament remained understood as divinely inspired and the revealed word of Truth. Aside from the remaining books to follow within the tripartite of the modern Old Testament, it was Athanasius who confirmed that the Old Testament count was 22. These were the same as those in the Masoretic Text and were in roughly the same order of the Protestant Bible at the time. Athanasius died in A.D. 365.

From among the remaining books of today’s Old Testament, there were historical books named and collated differently. For example, 1 Samuel and 2 Samuel were 3, and 4 Kings or Jeremiah is thought to have included Lamentation. Of the total 39 books currently in the Old Testament, they are found among the 22 recognized by how they were kept in ancient times.7 With other writings and texts combined and later separated, few other books were recognizing other books of Wisdom and the writings aside from the minor prophets. The sequence of historical recognition included the law, the major and minor prophets, and finally, the Writings (Hagiographa). Not in chronological order within the Masoretic Text, or Hebrew Bible, then and from what we have today, but by a sequence of assembly and later recognition. By the time the first century Christians arrived, Hebrew canon was set as canonical and authoritative, and no one dared, or have been so bold to take, add, or change anything to them.8

2.) Genre & Formation

As elaborated earlier, each of the three areas of the Old Testament has its own formative background. The law, the prophets, and the writings have their origins from divine inspiration and share commonality among the Protestant, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Ethiopian, and Syriac traditions. All categorical types of faith use the same Protestant Old Testament, but their order is somewhat different than what is found in the Hebrew Bible. The story about their collection and formation originates from the idea that the listed books of the Old Testament are a catalog of sacred texts. Such that the modes of communication were of a large literary range. From a study of hermeneutics, a student of Scripture immediately sees this wide range to express meaning in a way that goes beyond type designations as “the law,” the prophets,” and “the writings.” Genre pertains to a style of communication presented within Scripture to include explicit instruction, poetry, apocalyptical, wisdom, narration, and revelatory, among others.

These types within the Old Testament are partitioned by book but can also be found at a passage level as well. Interwoven among stories, proverbs, prophecies, hymns, songs, poems, genealogies, and historical references, are separate types that interface with one another as spoken or written by the patriarchal fathers and prophets from within the Biblical text. As one Biblical author writes within an area of Scripture and refers to these explicit types of genre. Even further, the substance of meaning by specific stories involving people, places, and events is often brought into view by the reader or listener of Scripture. From one passage, and one book to another, a continuous interface is progressively formed at an increasingly granular level. The propagation of historical and spiritual meaning as guided by God gives Old Testament writers a foundation and certainty by which truth unfolds for delivery to people of the relevant time period and even people today.

With continued conviction among historical figures in the Bible, readers of Scripture observe the divinely authoritative status of the written word as the Old Testament. From Josiah in 2 Kings 22 to the readings of Nehemiah, we see the preeminent attention placed upon God’s word as it was in use for the safety and well-being of the Lord’s people. In fact, during the time in which early Old Testament texts were collected, the Jews recognized the importance of Scriptural adherence in this regard. As written in 2 Kings 17:13, the Lord warned His people through every prophet and every seer that must “Turn from your evil ways and keep My commandments and My statutes, in accordance with all the Law that I commanded your fathers, and that I sent to you by my servants the prophets.” Their acknowledgment, comprehension, and compliance were necessary and made certain through oral tradition, but also by what was read and circulated from the prophets. Simply to illustrate and reinforce the authoritative nature of what was communicated to hold an enormous weight of meaning.

Along with the inspired canon of Scripture, there were various extra-biblical, or non-canonical writings read alongside the full canon. They were among peoples who inhabited Israel, Greece, Italy, the Middle East, and Ancient Mesopotamia. In addition to the authors of Scripture, there were numerous historical, philosophical, and deuterocanonical authors of a similar genre that gained the attention of many among the Jewish people and Gentile nations beyond. Ingrained into religious and pagan cultures from about 400 B.C. to the second and third centuries A.D., the pseudepigrapha writings occupied the thoughts and activity of those who were also subject to the full counsel of God’s word. The works of the Apocrypha,9 were also well-known and popular then as they are today. Recognized and accepted as ancient books of cultural and religious value, they were a substantial source of historical reference to deeper understand Biblical backgrounds.

While some within the Roman Catholic and Ethiopic Church systems accept the noncanonical apocryphal books alongside the canon, Protestant Christendom does not view them as carrying nearly the same weight. At least in terms of authority or inspiration as given to us by the Lord Most High in His revealed words through Scripture. To further elaborate on what the books of the Apocrypha were and where they were included, there is a virtual matrix to understand their noncanonical and widespread use. Codices Vaticanus, Sinaiticus, and Alexandrinus, to include the Peshitta, Vulgate, Roman Catholic Canon, Greek Orthodox Canon, and the Authorized King James Version (1611) all have a mix of different apocryphal books. However, generally, the inclusion of Apocryphal books is numerous across all texts.10 There are approximately 20 books of the Apocrypha to include Tobit, Judith, additions to Esther, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Baruch, Letter to Jeremiah, additions to Daniel, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, 2 Esdras, Prayer of Manasseh, Psalm 151, and Odes.

3.) Criticisms, Responses, & Implications

Liberal scholars of theology and the doctrine of Scripture advocate positions of authorial dating, origination, and content contrary to Scripture itself. In an effort to deconstruct the Biblical accounts of direct and indirect communication from Yahweh to His chosen people, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Joshua, David, and others, new dates of authorship are set, with authors other than what was written about in Scripture. For example, it is recorded in Joshua 1:8 that “this book of the law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall meditate on it in order to do all that is written in it.” If in context Joshua really could not have instructed the people of Israel to understand and know the Torah, or the first 5-books of the Bible, the books of the law because the text did not exist at the time, then deconstructionists are propagating error at best or a harmful lie. The contentious perspectives from those working against God’s word span across all three major divisions of the Old Testament.11 It appears in every area of Scripture, it is dissected and with attempts to thereafter “prove” forgery, or unsubstantiated social contributions to the origination, recognition, and assembly of Scripture. Where the attack is not on the message of Scripture itself per se, but its inspiration and ultimate source.

The specific criticisms of the books of the Law of Moses, the books of the Prophets and the Kethûbîm, or Writings, concern anti-supernaturalistic presuppositions that attempt to cast doubt on the authority and inspiration of Scripture. Therefore, to reduce or adversely affect the validity and effect upon its adherents. Particularly to damage its power to reveal the truth of God’s redemptive history and plan. By divine authority, the canon of Scripture is self-attested to demonstrate the valid substance of the Biblical authors at the time they wrote. The recognition and acceptance of intended readers were immediate down through the centuries, and contradictions otherwise are deceptive and likely nefarious to some extent. Speculative theories founded upon critical thought reveal a disconnect about dated times of authorship as compared to when actual events occurred, or when activity took place to give Scripture its content and meaning.

Canonical criticism concerning Old Testament canonicity was pioneered by Brevard S. Childs and James A. Sanders.12 The term canonical criticism was coined by Sanders as it introduced challenges to traditional studies in Biblical Theology and as new perspectives on interpretive developments were occurring in the 1970s. There was disagreement between Childs and Sanders concerning critical methods of Biblical analysis because Sanders held the view that biblical authority is outside the province of historical study. Furthermore, canonical criticism, from Childs’ view, is that the community and final form of the Bible largely shape canon and the authority of Scripture. A corresponding response from Sanders articulated a dispute to detail a valid method of interpretation itself from a historical and theological framework. A framework involving a process of prophetic hermeneutic of the writers of Scripture.13

Objections to Childs’ view of the community shaped canon began to form in defense of proper recognition of Biblical authority and historical accuracy. Christopher R. Seitz, in his work, “The Character of Christian Scripture: The Significance of a Two-Testament Bible, argues for an approach to canonical interpretation that takes into serious account the facts of history and its stages of development. In the context of original inspiration, an unbalanced and low view of Scripture must not rest too much on one testament at the expense of another.14 Others have argued a canonical approach to interpretation where through hermeneutics theological tension is somewhat relieved in favor of clarity and application. For example, any perceived tension between Paul and James in the biblical record is eased as suggested. Such that the epistle of James is written in support of the canonical timeline of the gospels to balance what some may view as an opposition of later Pauline epistles (see Robert W. Wall on James 4:13-5:6).

The debate between Protestants and Roman Catholics about the canon appears around the doctrine of Christ’s Incarnation. Where during the Reformation, the doctrine of “solus Christus,” which means “in Jesus Christ and in Him alone the Divine has become man, in him alone the revelation of God appears to us, in him alone God speaks to us,”15 we see a position of unmediated interpretation through the fallibility of people who were involved in the gathering and recognition of the canon. As everyone stands in a direct personal relationship with Christ, the doctrine of sola Scriptura then comes into view with its expression “for through the word of Scripture alone can man meet Jesus Christ directly.”From the Roman Catholic perspective articulated by Nicolas Appel, the intermingling of the human condition bears a problem and somewhat accounts for the struggle in canonical acceptance and recognition. This somewhat explains why some books of the Apocrypha appear within the Catholic Bible. Specifically, about how the interjection of the human condition affects the testimony of the Holy Spirit about the Word of God. Some would argue that this position remains unresolved.

Differences between a theological and historical process in canonical recognition stem from the doctrine of Incarnation specifically through Christ (Solus Christus; Protestant) as compared to Christ and the Church (Christus Totus; Catholic) as Christ inhabits His body by the Holy Spirit within the Church. Christus Totus in Latin means, “The Whole of Christ.” The incarnation of Christ in bodily form through Himself as Jesus the Messiah and the incarnation of the Holy Spirit through His body the Church. It is concluded that since the Holy Spirit bears witness to the truth concerning canonical Scripture, its pertinent recognition and acceptance comes from the Catholic Church. Not exclusively through canonical consciousness by the Holy Spirit’s work in Scripture alone (sola Scriptura). This view about the incarnation of Christ throughout Protestant and Catholic Christendom, therefore, has significant implications about the recognition, acceptance, and authority of Scripture which would affect worship and practice.

C.) New Testament Canon

The canon of the New Testament parallels that of the Old Testament. In the fourth and fifth centuries A.D., the New Testament was closed, and the consciousness of the canon was made clear through exegetical interpretation and sound hermeneutical practices. The work of the Holy Spirit began in the Scriptures to communicate the inspired word of the Lord. As the Old Testament was already canonized and in use among first-century Jewish peoples, it continued to gain acceptance and wider use among the Gentiles throughout the Greco-Roman world. As the writings, teachings, and oral traditions of the Apostles were making their way through the early church; there is little doubt that fledgling believers and followers of Christ were presented with the Old Testament subject matter as well. Details about the old and new covenants that concern the revelation and witness of the Gospel completed the full counsel of God’s word.

1.) Historical Developments

The underlying strength and authority of Scripture is supported by its canonicity. From the interconnected relationships within itself and throughout the Old and New Testaments, Scripture affirms its meaning across books or writings by genre. Historically, the Lord chose to use numerous authors over time to communicate revealed meaning about Himself, His plan, and what He has done through Creation. His activity to originate, configure, and maintain Creation in perfect order is accomplished through His word. Just as His word brings together all of Creation to accomplish His purposes, by God’s sovereign and perfect will, He is able to originate and inspire His written word where it is brought into existence and formed to accomplish His objectives. To demonstrate how our Lord accomplishes this, He uses means among fallible and sinful yet redeemed people through the work of the Holy Spirit (Luke 12:12, Luke 24:49).

Notice in Paul’s letter to Timothy that he refers to the Gospel of Luke as Scripture (1 Timothy 5:18). Incredibly, the work of Luke that records the words of Jesus “The laborer deserves his wages” is referred to by Paul as Scripture. Outside the Old Testament, the biblical text itself within the New Testament begins to form a historical perspective. Modeled for immediate church fathers to follow with the help of the Spirit of grace, no doubt (Zechariah 12:10). So down through time, over the course of history, we see the beginning of Scriptural meaning communicate in an interconnected way to stitch together both ancient codices and modern texts that serve as Holy documents that bring hope, wisdom, virtue, but most of all the revelatory intent of Yahweh.

We further see Paul’s letters referenced as “Scripture” by the apostle Peter (2 Peter 3:16). Paul was endowed “according to the wisdom given him” to demonstrate that just as our God spoke through the prophets, He did so through Paul, and here we have the apostle Peter in acknowledgment of that in truth and love. So first, we have Paul to Jesus, the second person of the Lord God incarnate referenced in Scripture as recorded in the book of Luke. Now we have Peter referring to Paul. As the communicative changes continue, we have Polycarp (125 A.D.), a disciple of John,16 as corroborated by Irenaeus and Tertullian, quoting Ephesians, 2 Timothy, and 1 John as Scriptures destined to the New Testament canon.17 Further along in time, Justin Martyr (150 A.D.), refers to the gospels as “Memoirs of the Apostles” in his First Apology discourse.18 Irenaeus (180 A.D.) refers to the fourfold form of the written gospels to indicate that there was a quantity of four written accounts of Jesus’ ancient biography and record as Scripture.19

Given there was a cascading sequence of Scriptural use occurrences in public life, and in personal study among the early church fathers, there were lists that began to form in forthcoming centuries that gave birth to the canon that the Church has today. From papyri to manuscripts, scrolls, and codices, the inspired content of the canon selected itself by various intertestamental references, and what belongs in the New Testament books were not originated from a human source. As various Gnostic and Montanist writings were rejected as formative lists were assembled, a clearer view of what the full counsel of God should look like in the form of the Holy Bible in the world today. To further elaborate on the genres and formation of the canon, various additional historical perspectives appear in antiquity. This was to demonstrate that there was a selection process concerning books of the whole Bible involving recognition, council review, affirmation, and acceptance. Not selection per se according to some vetting criteria, but by simple recognition of how Scripture held inherent value due to its subject matter as written by the inspiration of God and the Holy Spirit at work in the church at the time.

2.) Genre & Formation

Alexandrian Fathers, Clement and Origen, were largely responsible for establishing a canonical view of Scripture within the early church. As recounted by Eusebius of Caesarea (260 – 340 A.D.), there was again a tripartite grouping of Scripture as outlined and written about. All three categories constituted a body of writings that were produced after the revelation of Christ through His apostles by their witness, testimonies, oral traditions, and written work. Within these categories were the two separate second and third-hand series of recorded events within the first and second centuries. Standing among them in the first category were the homologoumena, later recognized as the four Gospels, Acts, the Pauline letters, Hebrews, 1 Peter, 1 John, and the Apocalypse (Revelation) of John. The second category was that of the Antilegomena, recognized as the questionable books of James, Jude, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John. Finally, the books that were not authentic, or accepted were The Acts of Paul, The Shepherd of Hermas, The Apocalypse of Peter, The Epistle of Barnabas, The Teachings of the Apostles, and the Apocalypse (Revelation) of John. One would notice that the book of Revelation was both in the homologoumena camp and the Antilegomena camp at the same time. Eusebius was, at times, uncertain about the canonical status of the book of Revelation, but he eventually recognized its acceptance and valid use within the Church as inspired Scripture.

The genres of the New Testament are varied as they are for the Old Testament. While there are no books of the law, wisdom, or poetry, produced within the New Testament, it consists of the Gospels of Christ, historical narratives, letters from apostolic fathers, and prophetic writings. As the term gospel translates from the Greek term euangelion,20its definition corresponds to “good news.” Prior to the use of the term in the New Testament, it was a word applied in another era concerning a victory of military conquest or political achievement. The gospels in the New Testament, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are narrative stories loaded with deep theological meaning and significance. They are ancient biographical stories of good news for people during the time of apostolic ministry. “To the ends of the Earth,” they are good news to everyone today.

The book of Acts is a narrative story, like the gospels. It is a story of theological history with deep and meaningful significance. It traces events and activities of the apostles throughout geographical regions in the Middle East and Asia Minor. Canonically, the book of Luke interfaces with the book of Acts as described within their content between Luke 24:49 and Acts 1 – 2. Specifically, instructions to remain in the city for power to follow from the Lord as written in Luke and then with the follow-up fulfillment of the promise. To include Christ’s ascension and the arrival of the Holy Spirit at the occurrence of Pentecost. The growth of the church, its persecution, Paul’s missionary journeys, and his encounters with culture to include political and legal systems provide a clear and natural transition from the gospels. Peter to share the gospel and build the church within Jerusalem while Paul also obeyed Christ’s commission to bring the same good news to Gentiles outside of Israel.

The New Testament canon includes the apostle’s letters that were produced from the early church. These were all of a correspondence genre that was read and circulated throughout the church at the time. Even today, the spiritual and theological development of this subject matter was regarded as Scripture as it is today (2 Pet 3:16, 2 Tim 3:16). Between Acts and the apostolic letters written to the churches in Asia Minor and to the Hebrews and Romans, there were disputes about their validity up through the centuries and still remain today with objections that surrounding authenticity, dating, and historical validity.

The book of Revelation as its own New Testament genre consists of three different literary types combined into one. It is a letter from John to seven churches in Asia Minor concerning prophecy and apocalyptic events to come. The three literary types of correspondence, prophecy, and apocalypse concern the revelation of Jesus involving judgment and events to come during the last days prior to His return.

Recognition of what books belonged in the New Testament canon was not obvious to the early church. There were numerous early lists that cataloged the written work of the apostles and authors to gather a full view of the inspired word of God as authoritative Scripture. Traditional dating from about 160 – 200 A.D., the earliest list was the Muratorian Fragment or the Muratorian Canon.21 While written in Latin, it was probably translated from an original Greek copy, and it still resides today in Milan, Italy. It consists of all the books of our New Testament today except Hebrews, James, 1 Peter, 2 Peter, and 3 John. This canon identified forgeries excluded from Scripture, and it accepted the Apocalypse of Peter for private reading.22

All the way from the first and second centuries, there were additional listings that formed up to the fourth and fifth centuries. Namely, formations from Origen of Alexandria (215 – 250 A.D.), Eusebius of Caesarea (311 A.D.), Cyril of Jerusalem (350 A.D.), Cheltenham canon (359 A.D.), Athanasius of Alexandria (367 A.D.), Amphilochius of Iconium (375 – 394 A.D.), and the Third Synod of Carthage (393 A.D.). The pattern of recognition among all of these formative canons was by iteration and successive approximation among different individuals to get to a final and closed New Testament canon. With all of these lists, the final recognized canon at the Third Synod of Carthage was that of Athanasius. The twenty-seven books of the New Testament were then formed, recognized, and accepted. From the Synod of Carthage, the canon of Athanasius was locked in place.

As these lists were produced separately and independently, a number of observations and suggestions are offered about what revealed the canon’s selected books of Scripture.23 Specifically, among the canonical lists and later all books in the New Testament, a pattern or criteria emerges to discount any idea that selection was arbitrary, incoherent, or without a sensible human rationale. Together the criteria or selectivity pattern included apostolicity, orthodoxy, relevance, widespread, and longstanding use.

3.) Criticisms, Responses, & Implications

Defending the canon from critics entailed quite a bit of effort against liberal scholars’ objections to the process of recognition and affirmation from councils long ago on ideological grounds. Namely, Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code is founded upon philosophies originating back to the emerging Gnostic era during the time of early church fathers. Bart D. Ehrman’s written work of “Jesus Interrupted” claims that the canon was the arbitrary selection of people among councils that did not put written works of the apostolic era up to vote.24 Where others were left out of the selection or recognition process of the canon. Others who produced lists of writings from among early Christians and church leaders were left out as they objected to the transpired formation of the canon to recognize and affirm God’s revealed word. Additional modern critics that object to the formation of the canon, inerrancy, authority, or tradition of Scripture include John Dominic Crossan, Marcus Borg, and John Shelby Spong.

Each critic that presents objections to the validity of Scripture, or the value and necessity of redemption, worship, service, and a life of faith generally come from a storied period of time in academic work who have had life experiences or hardships in their faith that caused a departure of orthodox critical thought. Their work in finding other books outside the canon, or to champion socially liberal worldviews more palatable to the culture of scholars inevitably make detailed, thorough, and self-justifiable efforts to work against Scripture and not with it to validate its meaning and truth. To apply a standard of humanistic rationale from presuppositions somewhat rooted in naturalism or unreconciled contradictions without explanation, assertions are concluded about errors in Scripture that remain unaccounted for to their satisfaction. Whether or not there are satisfactory explanations, or that there are no explanations whatsoever, in the view of the critical liberal scholar, there must be valid explanations answerable to human thought and reason as necessary to justify confidence or belief in Christ with or without the help of the Holy Spirit through the inspired Word of God as provided within the canon. There can be no justifiable or viable rationale about variances or errors among manuscripts found within the formation of the canon. Aside from the self-affirming nature of the canonical books of the Bible, there is an inferred insistence that all facts and details about revelatory writings line up according to the standards of scholars or liberal academic leaders that must abide by the requirements and social, behavioral, philosophical, and economical preferences of social pressures and personal inclinations even if they run contrary to the truth of Scripture.

Naturally, as false teachers, liberal academics, secular scholars, or apostates who learn about Scripture have an influence among the formative minds of people who seek the truth of God’s revealed word, critical observations, hasty conclusions, and obfuscation can have a deep and lasting negative effect on morality and the salvific status of individuals. Reminiscent of Bildad, Eliphaz, Zophar, and Elihu in the book of Job, even objective efforts among critics to understand and recognize the truth of Scripture can surface erroneous or deceptive conclusions. Propagated by lectures, written work, and social interaction that have implications of serious personal and social consequences. Unfavorable outcomes that break down social, government, family, and spiritual order inevitably bring about the demise of people at an unimaginable scale. Not due to an inability to recognize and understand Truth, but to accept and abide by it without causing harm to others. The absence of a commitment to Truth according to Scripture as revealed through the Holy Spirit by the work of the apostles and prophets lead to enslavement and misery in one form or another.

D.) Conclusions

Throughout this project, a substantial effort was made to research and communicate background, formation, development, and criticism details concerning the canon of God’s Word as revealed to the world throughout Scripture. Involving a wide-spread set of resources to get a topical yet comprehensive view of what occurred over the centuries to bring us the teachings and theological principles of the prophets, apostles, and God Most-High through our Lord Jesus. The Old and New Testaments together represent the full counsel of God’s Word. Just as the words, sentences, paragraphs, chapters, and genres convey substantial and everlasting meaning, the stitching together of books by various authors adds a progressive and revelatory way of recognizing what is necessary for the explicit will of God in Creation to include His redemptive work for humanity.

The fundamentals of the canon are necessary to understand across all eras from throughout the Middle East from the far reaches of Mesopotamia through Asia Minor and into modern Europe. With the earliest writings conveyed through the Pentateuch or the Mosaic Law, we see the beginning of what it is to recognize God’s written word from His own hand (Exodus 31:18). His message beginning with the people of Israel initiated a process or revelatory instruction that extends through a series of covenants across a timeline that reaches us today. From promises made to promises kept, we see the writings of numerous people of the Lord bring to humanity the stories, psalms, and songs of meaning from the mind of God. Book by book, authenticated by the inspiration by the Spirit of God, we have confidence that people can find Him by their time and effort spent engaged in His word.

The composite nature of Scripture is developed such that its modularity is coherent with overlapping, interlinking, and interwoven messages by narration and various types of suitable expression. It is a self-authenticating work of the Spirit of God, through His people to not only originate its substance as a recording of texts but also of their assembly. Beneath what was written about in historical activity and events of the Bible that testify to what occurred as prophesied and fulfilled. All the way from the garden to the ascension, we have an end-to-end view of what Truth is providentially given to us through the canon of God’s Word.

E.) Bibliography

1. Guinness World Records. Guinness World Records. 2020. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/best-selling-book-of-non-fiction (accessed March 10, 2020).

2. Grudem, Wayne. Systematic Theology, Introduction to Biblical Doctrine (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1994), 54.

3. Norman Geisler, William E. Nix. A General Introduction to the Bible (Chicago Moody Press, 1986), 221.

Van Pelt, Blomberg & Schreiner, Lecture 7: Seams in the Canonical and

4. Covenantal Structure, (2020) accessed March 11, 2020, https://www.biblicaltraining.org/library/seams-canonical-covenantal-structure/biblical-theology/van-pelt-blomberg-schreiner.

5. Dictionary.com, Antilegomena, 2020, accessed March 12th, 2020, www.dictionary.com/browse/antilegomena.

6. Archer, Gleason L. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction (Chicago: Moody, 2007), 64.

7. Sumner, Tracy Macron. How Did We Get the Bible (Uhrichsville: Barbour Publishing, 2009), 65.