The following are chapter notes from the book, “Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy.” The book is a compilation of essays from R. Albert Mohler Jr., Peter Enns, Michael F. Bird, Kevin J. Vanhoozer, and John R. Franke. The general editors are J. Merrick and Stephen M. Garrett. The textbook is in the Counterpoints of Bible & Theology Series. It was published in 2013 by Zondervan.

Chapter One: When the Bible Speaks, God Speaks: The Classic Doctrine of Biblical Inerrancy

The editors of the book “Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy” have put together a conversation in written form between academics who discuss the doctrine of inerrancy. The discussion is structured in a counterpoint format where four contributors frame the narrative with an opening statement to challenge thought and debate. Participants of the discussion include four prominent individuals within an academic context who bring together multiple perspectives about what inerrancy is. And if it is a valid way to understand and accept Scripture, its merits or flaws. Participants include Albert Mohler Jr (President of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary), Michael F. Bird (Anglican Priest, Theologian, and NT Scholar), Peter Enns (Author, Biblical Studies Professor), John R. Franke (Theologian, Professor of Religious Studies), and Kevin Vanhoozer (Theologian, Systematic Theology Professor).

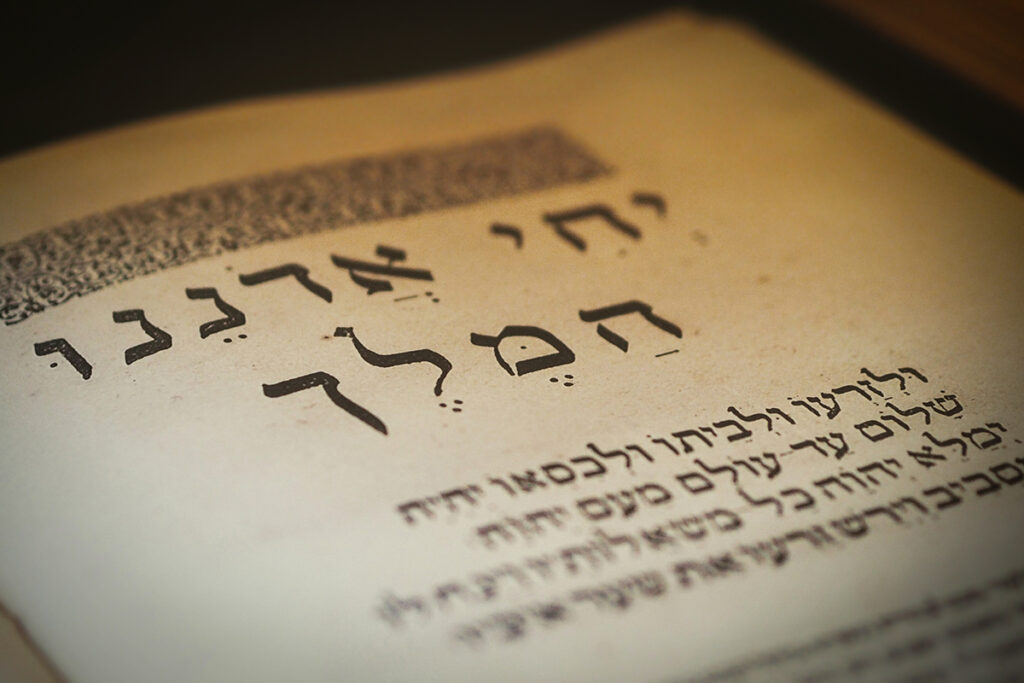

As anyone would understand the term inerrancy, a common definition is generally accepted as follows: “The idea that Scripture is completely free from error. It is generally agreed by all theologians who use the term that inerrancy at least refers to the trustworthy and authoritative nature of Scripture as God’s Word, which informs humankind of the need for and the way to salvation. Some theologians, however, affirm that the Bible is also completely accurate in whatever it teaches about other subjects, such as science and history.”1 In comparison, the Second Vatican Council defines it as: “Therefore, since everything asserted by the inspired authors or sacred writers must be held to be asserted by the Holy Spirit, it follows that the books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings2 for the sake of salvation.” 3 To further recognize Protestant or Evangelical attestation of inerrancy, the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy (CSBI) is widely understood as informative to clarify what is meant and accepted as Scripture inerrant of facts and truth.

Mohler offered the prescriptive “When the Bible Speaks, God Speaks: The Classic Doctrine of Biblical Inerrancy” to open the first of a five-part series of declarations. He makes a case for inerrancy as Scripture is a testimony to itself while serving the faith and needs of the Church. To anchor the testimony of God’s Word as trustworthy, Mohler makes a further compelling and persuasive point that Scripture corresponds to God’s personal nature as his own self-revelation (44).

According to Mohler, our comprehension and understanding of God’s Word to support formulaic doctrines are not freestanding. A theology stems from God’s Word as it produces a realism to “affirm the irreducible ontological reality of the God of the Bible.” As “God wrote a book” (45), Mohler affirms that human authors were guided into truth and protected from all error by the Holy Spirit. The absence of error, as a result, explains the propositional value of inerrancy. As such, the terms infallible and inerrant reject the claims the Word of God is theologically incorrect or without truthfulness in its intent to bring salvific, theological, and historiological messaging to its readers.

Therefore, it is affirmed by the CSBI that the Word of God constitutes plenary inspiration for faith and practice. It is helpful as it is authoritative for belief and instruction.

Chapter Two: Inerrancy, However Defined, Does Not Describe What the Bible Does

As ideological fencing was placed by Pharisees who set up regulations around the Mosaic law, they did so to provide insulative barriers at some distance to prevent people from breaking the Old Testament covenant after their return from Babylonian exile. By comparison, it intuitively seems like evangelicals set up theological fencing around the doctrine of inerrancy to prevent people from corrupting the closed Biblical canon and the interpretive meaning of Scripture for valid soteriological purposes. As Enns referred to John Frame’s view about inerrancy as a theologically propositional idea, he wrote that he would rather do away with the term but could not do so because of certain corruptions to follow from theologians (scholars).4

Before Enns began to deconstruct each of the three test cases of Biblical inerrancy initiated by Mohler in chapter one, he spent considerable effort on the disharmony of evangelicals over inerrancy (i.e., socially liberal objections to Scriptural authority) and the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy (CSBI). He grieves over the disconnect between academics and inerrantist evangelicals over the doctrine of inerrancy, and he makes clear that it sells the Bible short. Enns also declares that inerrancy sells God short as it is merely a theory of inferior purpose. In his view, it’s a doctrine that needs to be scrapped as it preempts discussion about scholarly conclusions about Scripture’s accuracy, facts, and truths (or at least evangelical interpretation of it). Through Enns’ perspective, it is clear that some academic scholars are certain inerrantists are intellectually dishonest (84) and a disservice to culture as ineffectual spiritual witnesses.5

To add further detail to Enns’ objections to the CSBI, he walks through each of its four assertions point-by-point. All four assertions pertain to the authority of Scripture, its witness of Christ and the Holy Spirit, its commitments to faith, life, and mission, and discontinuity between lifestyle and faith claims of inerrantists. Stemming from each, as there is his distinction made between authority and inerrancy, this is deconstruction. As God’s testimony of himself is true, His Word is undoubtedly accurate without error by extension. Conversely, Enns supposes that as inerrantists view the inseparable linkage between authority and inerrancy, that is a perspective should require a defense. The type of authority recognized by inerrantists is questioned in a further effort to dilute the purpose and intent of the CSBI as merely an affirmation document. The CSBI carries no creedal weight, but it is simply a point of reference or a marker to ascertain what someone concludes or supposes about the nature of Scripture, its truth claims, self-witness, and testimony. Enns and like-minded evangelicals prefer to eliminate the doctrine to render it subject to open-ended critical interaction.

While Enns wants to see “a valid definition of the word truth” (87), he wants Scripture held up to critical review without immunity to our interpretive cultural assumptions. It appears he wants the plain truth and meaning of Scripture and its message rendered impotent to guide and protect believers. Consider the interchange between Jesus and the religious leaders of John 8:12-58 as it concerns how He defines Truth of Himself and that of the Father. By His verbal expression of meaning, it is absolute and without error.

Finally, in so many words, Enns says he genuinely wants to introduce a way to make Scripture compatible with scholars’ research concerning ANE facts, archeological discoveries, and literary analysis of ancient civilizations. So Enns wrote what he thought about an “incarnation model” as an alternative in opposition to the doctrine of inerrancy. An “incarnation model” was set up as a counterpoint to an “inerrancy model” to frame the discussion with a new category of false or foreign meaning. As if generations of the doctrine of inerrancy had no bearing, it was set up as an objective comparison or alternative to inerrancy overall to include the CSBI statement. Contributors Bird, Franke, and Vanhoozer’s views about what Enns wrote weren’t comprehensive or well developed, but they revealed a tension between the doctrine of inerrancy and the incarnation model as if there was something to explore further according to Enns’ perspective.

To consider what the incarnation model implies, Bird’s restatement of John Webster’s view is an eye-opening refutation: “this incarnational model is, as John Webster calls it, ‘Christologically disastrous.’ It’s disastrous because it threatens the uniqueness of the Christ event, since it assumes that hypostatic union is a general characteristic of divine self-disclosure in, through, or by a creaturely agent. Furthermore, it results in a divinizing of the Bible by claiming that divine ontological equality exists between God’s being and his communicative action.”6 Moreover, Irenaeus of Lyons (130-230 A.D.), a disciple of Polycarp, separated incarnation between the Word and Christ within his work Against Heresies. He wrote of the incarnation of Jesus but not of the Word itself to exclude incarnational participation. To quote Irenaeus, “For they will have it, that the Word and Christ never came into this world; that the Saviour, too, never became incarnate, nor suffered, but that He descended like a dove upon the dispensational Jesus; and that, as soon as He had declared the unknown Father, He did again ascend into the Pleroma.” 7

Chapter Three: Inerrancy Is Not Necessary for Evangelicalism Outside the USA

The book’s third part, Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy, entitled “Inerrancy is Not Necessary for Evangelicalism Outside the USA,” concerns Michael F. Bird’s views on American understanding of inerrancy concerning the CSBI. Without much interaction with inerrancy in general as a contribution to the work of the book about Biblical Inerrancy, there is an absence of the distinction. The work of chapter 3 in the text is primarily a discourse on affirmations, objections, and concerns about the CSBI. As Bird narrows his thoughts around the particulars of the CSBI, he goes well beyond the purpose and intent of the Chicago Statement’s purpose of upholding the doctrine of inerrancy. Bird takes exception to various points of CSBI inerrancy verbiage around the Biblical creation account in Genesis. He would presumably agree that the truth and principles of inerrancy refer to the trustworthiness and authoritative nature of God’s word as authoritative.

From Bird’s various perspectives, he would not entirely affirm what the Bible infers about other subjects such as science and history. In fact, Bird’s views about inerrancy are better stated as a better categorization of veracity. From the inner witness of the Church by the Holy Spirit, Scripture’s “divine truthfulness” (158) is a way to set aside the claims or proclamations of negative statements in defense of “inerrancy.” Whether on its own merits or as an apologetic expression of the CSBI by American evangelicalism concerning the doctrine inerrancy or inspiration of Scripture.

What the Bible says about itself pertains to its use and inspiration (2 Tim 3:16). Among the various genres of Scripture, the Old and New Testaments are attestations of divine truth whether in narrative, poetic, prophetic, apocalyptic, epistolary form. Scripture best interprets Scripture and reservations about exceptions concerning inerrancy as it does so, whether supported by the CSBI or not, isn’t productive on the grounds of harmonization, literary discrepancies, nation of origination, or supposed contradictions without historiographical refutation. Particularly when so much antipathy exists around the meaning and purpose of God’s Word as it is intended by define revelation for God’s glory and for salvific outcomes. The doctrine of inerrancy doesn’t claim for itself authority over matters concerning self-contradictory postmodern assertions (i.e., opposition to absolute truth and authority). The CSBI and the doctrine of inerrancy are assembled to support a high view of Scripture toward confidence for its intended purpose.

Some objections to inerrancy appear to stem from the term itself. As the Word of God is without error and reliable as God is Truth, Bird calls attention to its comparative infallibility and inspiration. Bird doesn’t indicate that the Word of God is with error or without truth, nor does he suggest that it is uninspired. His reservations are around what interpreters understand about the idea of inerrancy and how that pertains to conclusions involving life and practice. Particularly across cultures of different nationalities that do not hold to the doctrine of inerrancy, especially as it is defined and understood in the West or America more narrowly.

The difference between inerrancy and infallibility is essential and necessary to recognize and understand. To put it clearly, inerrancy, at a minimum, refers to the trustworthy and authoritative nature of God’s word for salvific purposes. By comparison, infallibility refers to Scripture’s inability to fail in its ultimate purpose of revealing God and the way to salvation. It is counterproductive to conflate the two terms or to use them interchangeably. The doctrines of infallibility and inerrancy are not for a social utility or to shape social justice initiatives for society or the State. While Catholicism shares the same definition of inerrancy as Protestantism, it differs in defining infallibility. Infallibility within Catholicism includes the church (i.e., the magisterium and its dogma) under the pope’s authority.

Bird’s assessment and criticism about tirades against God’s Word is exactly the correct posture against those who stand in opposition to its truth, authority, reliability, and inspiration of Scripture. However, it isn’t so much secular culture or atheists who so much pose a harmful threat to the doctrines of inerrancy and infallibility as does Christian academics or scholars, well-meaning or not. It is for internal reasons of mishandling God’s Word that it is served by assertive statements of inerrancy to prevent its surrender to a multitude of professing Christians who have a large range of worldviews (including liberalism, or socialism) and would rather see God’s Word rendered insufficient and irrelevant to a postmodern society. Professing Christians, especially progressive Christians, are just as readily inclined to make God’s Word into its own image as secular society.

Unrelated Note: In support of feminist egalitarianism, Bird makes an inflammatory assertion that complementarians enable abuse: Article

Chapter Four: Augustinian Inerrancy: Literary Meaning, Literal Truth, and Literate Interpretation in the Economy of Biblical Discourse

As affirmed by Vanhoozer, the doctrine of inerrancy has an important presupposition. That most important presupposition is: God speaks. Or, more specifically, God the Creator communicates through human language and literature as a means of communicative action to people. Vanhoozer also points out that the works of the Trinity are undivided (opera trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt) as triune discourse indicative of communicative action involving subjects, objects, and purpose. He makes the case that language is functional and cognitive in nature to support the intent of divine revelation. Therefore, it is recognized that Scripture is a corpus of written communicative work consisting of historical assertions, commands, and explanations. According to Carl Henry (20th-century theologian), Scripture is propositional, but it is also trustworthy as true as it is a correspondence of Christ’s witness to what and who God is.

Inerrancy is a claim that the Bible is true and trustworthy through critical testing and cross-examination. Just as Augustine speaks of the incarnation as humans give tangibility of thoughts as words, Christ is the exact imprint of God’s being (Heb 1:3). Jesus is the image of the invisible God (Col 1:15) and what Christ speaks is Truth because He originates as God from the Father who is Truth and communicates truth. Whether verbally while with us in Creation or in Scripture by the testimonies of eye-witness accounts of his verbal speech acts. Within the old or new covenants, by God’s presence or His Spirit among people, He cannot lie in Scripture as His personal veracity is made clear through the inspiration of the Canon.

As made evident through divine revelation, truth is a correspondence of covenantal and redemptive meaning. The modes of its conveyance have a bearing on the methods of truth messaging by which it is delivered and understood. Allegory, metaphors, poetic expressions, and narrative discourses together establish the means of language utilized to accomplish its desired intent. Therefore, as Vanhoozer proved, it isn’t helpful when critics of inerrancy confuse matters by suggesting that inerrantists believe every word of the Bible as literal truth. Vanhoozer distinguishes between “sentence meaning” and “speaker, or writer meaning” when readers seek to understand what the author is doing or saying within Scriptural messaging. Analogies defy critical assertions about literalist interpretations of meaning.

Literalism, irrespective of context, can produce contradictions in meaning. Or it can confuse the intent of messaging through various linguistic methods, especially as prophecies and parables were verbally uttered and recorded in Scripture to convey imagery or parallel thoughts and ideas to achieve Spiritual understanding among listeners or readers. The communication method and its content are intentional, just as the assembly, formation, and preservation of God’s Word are true, sure, and lasting for those of faith to believe.

Inerrancy doesn’t claim to affirm or validate scientific or philosophical observations and constructs precisely. Observations of physical behaviors and explanations of metaphysical reality originating from beings in natural order don’t have reach to ascertain spiritual truth and meaning as propositioned and asserted from God’s Word. Supposed contradictions in Scripture that serve as proof-text “gotchas” do not subvert the inerrant truth and meaning of intended spiritual messaging, and theological truth held out as spiritually factual from different authorial perspectives. Even with elaborate and effective explanations to reconcile apparent differences, there isn’t much acceptance to recover veracity among many who object to the doctrine of inerrancy.

Whether believers or unbelievers interpret Scripture according to cognitive reason and comprehension for rational thought and conclusion, gathered facts can become assembled incorrectly to arrive at false notions of belief or disbelief. To quote Vanhoozer, “God’s words are wholly reliable; their human interpretation, not so much” (224). To further explain, biblical inerrancy requires biblical literacy. It is a yoke of burden that people of postmodern culture view Scriptural literality by its terms and expectations of meaning. People within modern society expect a reality of the time of the Old and New Covenants to conform to how things are expected today. The claims of inerrancy do not imply there is only one way to map the reality of the world correctly, either then or now. Proper hermeneutical stands separate from inerrancy as necessary to understand and accept Truth from Scripture.

Chapter Five: Recasting Inerrancy: The Bible As Witness to Missional Plurality

John R. Franke’s contribution to the evangelical conversation around inerrancy is driven by his aspirations around what he calls a plurality of truth toward God’s missional objectives. By missional theology in keeping with the mission of God, Franke means humanitarian relief and advancement as chief of concerns. When Franke speaks of missional imperatives that involve the gospel and discipleship, it is always within a social and cultural context to improve the human condition. To Franke, the meaning of Scripture as inerrant is not so much about its salvific relevance as humanity is lost in sin and stands condemned without redemption. The authority of Scripture as a witness to the mission of God comes from the truth claims of Christ and the veracity of His words as He is the incarnate expression of God.

Franke’s sympathy toward postmodern theology explains his objections to static biblicism. The Spirit continues to speak through Scripture as he puts it but doesn’t offer thoughts about the meaning and purpose of Holy Spirit inspired Scripture for the actual gospel purpose of salvation and restoration of people to God. Franke’s contribution rests very much on the here and now for people in terms of missional objectives, not the already but not yet. The concern isn’t so much that people are perishing and headed toward hell, as it is their earthly well-being. The concern should rather be primary-secondary prioritization from a missional perspective. The truth of the Old and New Covenant’s meaning entirely revolves around how humanity would return to God. The confidence believers have about what Christ does to reconcile people to God comes from truth spoken and written without error and infallibly. With authority, believers can meet people’s spiritual and physical needs by missional endeavor rooted in sound theology and a commitment to the truth claims of Christ and God’s Word at work.

As Franke writes, “I believe that inerrancy challenges this notion and serves to deconstruct the idea of a single normative system of theology” (277), he is revealing his thoughts about what postmodern progressives do to reject conformity to the text of Scripture “for the sake of systematic unity.” The assertion illegitimate interpretive assumptions make clear postmodern thought, as there is no acceptance of universal truth. According to Franke, truth must be plural to accomplish contextual missional objectives relative to individual interpretation from Scripture. As conventionally defined by Protestants and Catholics, the doctrine of inerrancy is recast by Franke as an open and flexible tradition for pluralistic perspectives, practices, and experiences. It is unacceptable to Franke that the whole Bible is interpretive as an inerrant description of the gospel and Christ’s commands to love God and neighbor. Essentially, it is his call to redefine inerrancy such that the Bible is what we make of it and not what the authors intended.

Franke’s final thoughts about the cultural relevance of the gospel bring further alarm as he calls on his readers to surrender universal and timeless theology. He attempts to message a desire to redefine inerrancy to accomplish a culturally relativistic notion of God’s Word. That is, to rewrite Scripture to shape truth suitable for cultural conditions toward various human interests aside from salvific reconciliation. Where truth as concrete or abstract meaning carries less utility to accomplish objectives and instructions explicitly set forth by the Creator. Objectives and instructions delivered through human language expressed in truth as God is truth that must be accepted and theologically contextualized without compromise. It is crucial to ensure there is no loss or corruption of meaning. It is necessary to further God’s kingdom and bring people together in redemption toward their salvation and physical well-being without surrendering absolute truth and our acceptance of Scriptural authority.

Citations

__________________________

1 Stanley Grenz, David Guretzki, and Cherith Fee Nordling, Pocket Dictionary of Theological Terms (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1999), 66.

2 cf. St. Augustine, “Gen. ad Litt.” 2, 9, 20: PL 34, 270–271; Epistle 82, 3: PL 33, 277: CSEL 34, 2, p. 354. St. Thomas, “On Truth,” Q. 12, A. 2, C.Council of Trent, session IV, Scriptural Canons: Denzinger 783 (1501). Leo XIII, encyclical “Providentissimus Deus:” EB 121, 124, 126–127. Pius XII, encyclical “Divino Afflante Spiritu:” EB 539.

3 Catholic Church, “Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation: Dei Verbum,” in Vatican II Documents (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2011).

4 John M. Frame, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Christian Belief (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2013), 598.

5 Cited by Enns: “For a focused critique of the CSBI (and its later sister document the Chicago Statement on Biblical Hermeneutics 1982), see Iain Provan, ” ‘How Can I Understand, Unless Someone Explains It to Me?’ (Acts 8:30–31): Evangelicals and Biblical Hermeneutics,” BBR 17.1 (2007): 1–36. See also Carlos Bovell, Rehabilitating Inerrancy in a Culture of Fear (Eugene, Ore.: Wipf & Stock, 2012), 44–65; Kevin J. Vanhoozer, “Lost in Interpretation? Truth, Scripture, and Hermeneutics,” JETS 48, no. 1 (March 2005): 89–114. For an appeal for a more prominent role the Chicago statements should play in evangelicalism today, see Jason Sexton, “How Far beyond Chicago? Assessing Recent Attempts to Reframe the Inerrancy Debate,” Themelios 34 (2009): 26–49.”

6 Peter Enns, “Inerrancy, However Defined, Does Not Describe What the Bible Does,” in Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy, ed. J. Merrick, Stephen M. Garrett, and Stanley N. Gundry, Zondervan Counterpoints Series (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2013), 125.

7 Irenaeus of Lyons, “Irenæus against Heresies,” in The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 427.