The purpose of this post is to bring into view the ancient Neo-Babylonian empire and its long-term permanent effect upon the people and place of both Jerusalem and Judea of the Old Testament.

Introduction

Throughout numerous literary genres within the Old Testament were continued warnings by the prophetic voice and growing geopolitical circumstances throughout the Mediterranean region. The biblical historicity of the Neo-Babylonian empire gives deep and lasting theological messaging to captivate the hearts and minds of those who want to understand what Yahweh did to accomplish His sovereign purposes as He imposed upon the people of ancient Judah and its inhabitants at the capital of Jerusalem. Before, during, and after the upheaval and trauma brought to the people of Judea, Yahweh originated and shaped an empire of extraordinary power and strength to serve Him as an instrument of judgment, destruction, and displacement upon His people (Jer 21:7).

The Neo-Babylonian empire was formed and given the power to execute judgment upon Judah after it had plunged into apostasy by rejecting Yahweh through numerous covenant violations. Specifically, the people of Yahweh became involved in the widespread practice of idolatry, social injustice, and religious ritualism.1 This paper attempts to demonstrate the outcome of covenant disobedience by describing the circumstances and conditions placed upon the people of God by the Neo-Babylonian empire. This research and analysis are an attempt to answer some questions about what life was like in Babylon. Particularly for the people of Yahweh as they went through their time of siege, captivity, and exile. The predatory nature of the Neo-Babylonian empire was a hammer on the hot iron of Israel’s history.

Background

Neo-Babylon’s rise to power was preceded by other powerful and notable historical figures, such as Hammurabi, the Amorite of ancient Old Babylonia.2 Babylon’s presence among the surrounding table of nations became prominent through its advancements in civilization, but also over its rivalries, prior to the arrival of Israel in the land of Canaan. From continents in all cardinal directions, the nations of Egypt, Assyria, Persian, Media, Anatolia, Edom, Moab, Arabia, and others along the circumference of the Mediterranean Sea were dispersed around Palestine inhabited by the nation of Israel. Whether divided or united, the Northern and Southern Kingdoms of Israel were subject to the physical and spiritual pressures of people unlike them.

The geographical, political, social, and religious topography, of the regions surrounding Judea just after the time of the divided monarchy of Israel, presented a continuously corrosive influence upon the people of God until the incremental and certain conquest of the Babylonian empire was brought upon them until their inevitable, prophesied, and collective destruction (Jer. 46-49). Replete through Jeremiah’s account are the judgments of the nations called out by name. To include Judah and Jerusalem to eventually return to Babylon itself, the anger and judgment of Yahweh were upon nations. To execute divine punishment, Yahweh chose to rise up a fierce and undefeatable army with a leader that was militarily well-developed. Nebuchadnezzar II was the King of Babylon and its military leader at the time of its campaigns across the Ancient Near Eastern nations, as specified by the prophet Jeremiah. However, before the onslaught of Babylon toward the many nations under judgment, Nebuchadnezzar’s predecessors needed to defeat Assyria and its king.

In 722 B.C., Assyria invaded the Northern Kingdom of Israel (Samaria) through the leadership of Sennacherib. Assyria wiped out the Northern Kingdom of Israel and came to dominance throughout the region, while Judah progressively became further threatened and isolated until its destruction as prophesied (Isa. 39:6). The Neo-Babylonian empire would eventually confront and defeat Assyria through its rise to power until it finally collapsed in October of 626 B.C.3

To set the stage for Neo-Babylonian dominance, Nebuchadnezzar’s father Nabopolassar needed to destroy the cities of Assyria to include Nineveh, Haran, and Carchemish, even with Egyptian support from the South. As Yahweh rose up Assyria, and its king Sennacherib, as an instrument of judgment upon the Northern Kingdom of Israel, He also prepared Babylon to do the same with the Southern Kingdom of Judah. All the while, the newly formed Babylonian empire would execute judgment upon Assyria. Yahweh put together an instrument of divine justice through which He would destroy Jerusalem, Judah, and the neighboring nations. This is the historical scene in which the deportations, exile, and life in Babylon would begin for the Lord Yahweh’s people. As the Babylonian assaults upon Jerusalem and Judah would commence, the Babylonian exile became inevitable for God’s people of Israel.

Chronology

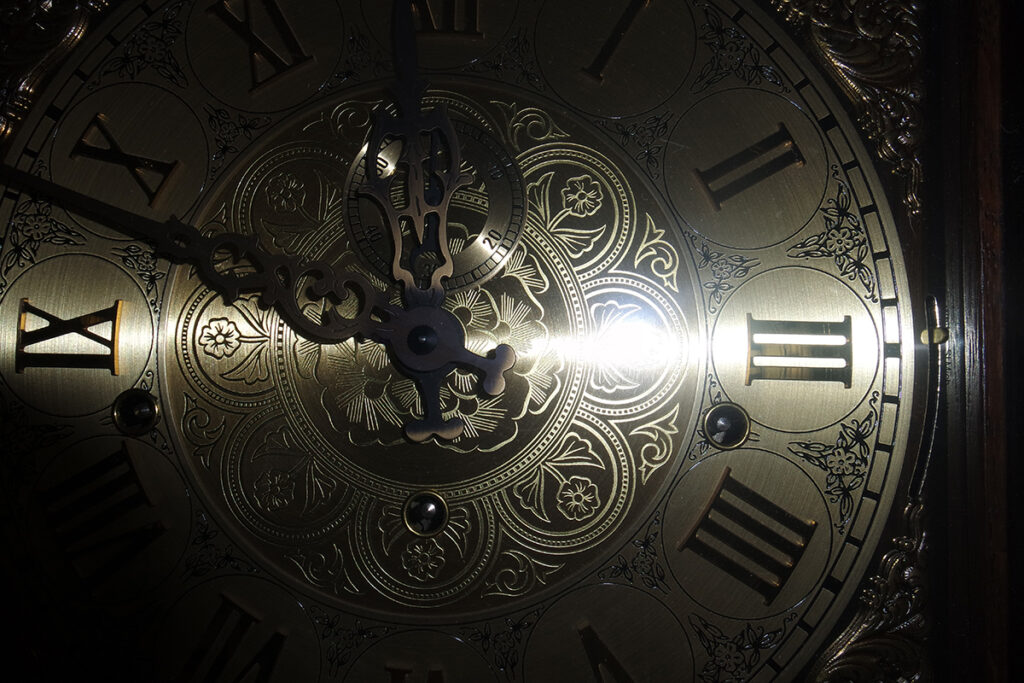

To see the scope of Israel’s plight, it is necessary to consider the timeline before, during, and after Yahweh’s judicious use of Babylon. Moreover, by looking across the course of events, it becomes evident that the Neo-Babylonian empire’s prescribed growth was predicated upon its defined purpose as intended by Yahweh. The intervals of time across the span of Babylon’s existence highly suggest that Yahweh raised the empire to serve a sovereign purpose.

By comparison, the author of Romans wrote that Yahweh raised the pharaoh of Egypt to show His power. And for His name to become known all over all the earth (Rom. 9:17). So, it stands to reason, just as Yahweh raised up the pharaoh of Egypt to oppose the exodus of the Hebrews from Egypt, He rose Nebuchadnezzar II of the Neo-Babylonian Empire to evict Israel from Canaan, their land of promise. As a cycle of epic events at a macro level, from Egypt to Assyria and Babylon, the same theme of transition under duress occurred.

Ante Neo-Babylonian Period

After the Assyrian conquest that involved the captivity of the Northern Kingdom of Israel, there were several decades of inactivity from Babylon until Nabopolassar rebelled to eventually prevail and establish footing as a nation independent of its oppressors. Once Nabopolassar became King of Babylon, a rapid succession of events, between 612 B.C. to 597 B.C., transpired where the newly situated empire became cemented in history as the latest superpower to begin its conquests of numerous nations. Most notably beginning from the battle of Carchemish in 605 B.C., Assyria and Egypt together were defeated to assure no further opposition could impede Babylon’s raids and further territorial exploits. 4 The high concentration of activity right up to the capture of Jerusalem speaks to what the prophet Isaiah earlier foretold (Isa. 39:1-8, 2 Kgs. 20:12-18) to Hezekiah.

Post Neo-Babylonian Period

The Neo-Babylonian Empire was short-lived. From the time Nebuchadnezzar II’s father became King of Babylon in 626 B.C. to its fall to the Persians in 539 B.C. (Dan. 5:28), its dominance was a mere 87-years. As the duration of Judah’s captivity was 70-years (Dan. 9:2), the rough time alignment attests to what the purpose of the Neo-Babylonian empire was.

King Nebuchadnezzar was given rule over Babylon to prosecute conquests and develop the city into a functional state to host Judah and those of the diaspora. Nebuchadnezzar’s reign only lasted 42 years (605 – 562 B.C.).5 Moreover, Babylon became a short-term generational host until the time of the exile was fulfilled when Yahweh would again redeem Israel and bring them back into the land of Canaan (Jer. 32:15).

Once Babylon fell to the Persians in 539 B.C., the Ruler of Persia would become yet another instrument of Yahweh. Where the people of Israel would become liberated, Cyrus the Great granted the people in captivity the authorization to return to their land and resume their lives. While the historical account would make it appear that the intellectually astute King of Persia would permit the return of the Israelites, it was Yahweh all along who called and gifted Cyrus the Great.6 It was Isaiah the prophet who spoke of Cyrus as the “shepherd” of Yahweh (Isa.44:28) to subdue the nations once again as Babylon did before.

Campaigns

The first time Jerusalem’s occupants were deported to Babylon was in 605 B.C. A few years before that, Nebuchadnezzar invaded and destroyed Ashkelon of the Philistine people. Once the battle of Carchemish in Northern Mesopotamia was won, Nebuchadnezzar set out on a multi-year attack on numerous territories, including Gaza, Ekron, Egypt, Lachish, Elam, Tyre, and Anatolia, plus various others East of the Jordan river. His efforts concentrated South of the Fertile Crescent, and he invaded Jerusalem four separate times. The most significant occurrence was in 586 B.C. when Solomon’s temple was destroyed, but the people were deported for the third time. Later, in 582 B.C., Nebuchadnezzar deported Jews to Babylon a final time.

The catalog of targeted nations was historically outlined by the prophet Ezekiel comprehensively (Ezekiel 25-29). These seven nations under judgment also correspond to the prophet Jeremiah’s separate prophetic messages (Jer. 46-51). Moreover, Ezekiel made no mystery of what was to occur in Jerusalem during his ministry. Through acting out the forthcoming exile, the captivity of Judah was symbolized from his role-play by carrying baggage within sight of those with the city (Ezek 12:1-7). Ezekiel prophesied what has to befall Jerusalem and Judah by the Babylonian Empire (Ezek 12:13).

Invasion of Judah

By comparison to Jerusalem and other nations, the extent of destruction throughout Judah was relatively modest. At least archaeological research indicates discoveries that prove Nebuchadnezzar’s assault on Lachish and various other cities.7 The Lachish Ostracon IV, the Lachish letters discovered at Tell ed-Duweir in 1938 in Southern Palestine, indicates correspondence immediately before the siege of Babylonian forces at their walls.8 The devastation in Judah was of a direct bearing upon the entire land of promise. Yet, it is also of significance that Nebuchadnezzar assaulted Hazor in Northern Israel (Jer. 49:28).

As a matter of strategy, the conquests of Babylon were about the business of building an empire. Through strength and power by military force, King Nebuchadnezzar II plundered the treasures and valuables where they were searched and looted.9 Namely, of areas that possessed existing material resources, or wealth, and demonstrated an ability to pay tribute, produce labor, and assume vassal status to the formative Babylonian empire.

Siege of Jerusalem

The historical record of Nebuchadnezzar II’s siege against Jerusalem is confirmed across various passages of Scripture (2 Kgs, 24:20-25, Jer. 52:3-4, 2 Kgs 25:1, Jer. 39:1, 52:4). Israel’s reliance upon Egypt as allies to defeat the forces of Babylon proved ineffective. In fact, the Babylonian’s defeat of the Egyptians and Assyrians at Carchemish (Jer. 46:2) was a foreboding event to indicate further trouble ahead. Yahweh already foretold through His prophets that the new empire would prevail and that they would become subjugated to it (Jer. 4:16, 27). There was nothing that the leaders and occupants of Jerusalem could do to prevent the forthcoming judgment and onslaught once Yahweh’s people reached the point of no return. Jerusalem refused to repent (Jer. 5:3).

It was apparent that the lessons of Babylon’s predecessors against Northern Israel were not enough to inform them of what would happen to Judah. Sennacherib’s military exploits that destroyed Israel only about 136 years earlier (722 B.C.) did not make it clear enough to the people of Jerusalem and Judah what devastation would come to them. Correspondingly, the people of Southern Israel knew of impending judgment and disaster. Still, they did not heed the expected loss of life, possessions, and the land of which they were blessed in exchange for their return to covenant obedience to Yahweh.

The siege of Jerusalem is recounted in 2 Kings 24:1-7. The Babylonian Chronicle itself refers to the siege of Jerusalem (B.M. 21946; Jerusalem Chronicle) to corroborate the beginning of Nebuchadnezzar’s siege upon the city.10 With limited details about siege methodology, one could conclude that the type of siege machines applied during the battles against Assyria was applied to Jerusalem in due fashion.

Deportations to Babylon

There were four total major deportations from Babylon to Jerusalem over a duration of time. The first three deportations were in succession at intervals of time that correspond to changes in kingly rule over Jerusalem before and after it was destroyed. The first deportation under king Jehoiakim, appointed by Pharoah Neco of Egypt, occurred in 605 B.C. as Judah experienced a change in its vassal status from Egypt (609-605 B.C.) to Babylon (605-598 B.C.). To further empty Jerusalem, the second major deportation occurred in 597 B.C. under the leadership of Jehoiachin (Jehoiakim’s son). To correspond to the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, the city was further depleted of its population in 586 B.C. The fourth and final major deportation occurred in 581 B.C. (2 Kgs 25:8-21) as Judah was relegated to a dependent province under the governorship of Gedaliah (2 Kgs 25:22-26) as appointed by Nebuchadnezzar.11

Captivity and Exile to Judah

The time of Babylonian exile for the people of Israel was crucial in their history. Most especially concerning their condition and reflection upon their circumstances and punishment as a guilty people before Yahweh. While in exile, they no longer had a temple to worship within, and while in exile, they had a multitude of transgressions to contemplate (Lam. 1:5). They were guilty of Baal worship (Jer. 32:35) and oppression of the poor (Jer. 5:28-29). As the people of Yahweh, Judah was situated in a foreign place to realize that He controls empires and shapes the events of history.12

Through the prophet Jeremiah, Yahweh instructed the people of Judah to settle in and live lives of relative normalcy while in captivity. Until their return decades later, they were to integrate into Babylonian society, participate in the economy, take up employment, and become productive members of the society. In Jeremiah’s letter to the exiles (Jer. 29:1-23), Yahweh specifies the duration of their exile (70-years) and instructs His people to pursue marriage, bear offspring, and guard against the deception that could set them adrift away from their devotion to their God. The biblical and theological point of the exile was to return the people of Judah to Yahweh.

Babylonian Dominance

During the time of the exile, while the people of Israel were rehabilitated, Babylon continued its dominance throughout the regions it conquered. Through its military campaigns, infrastructure development, territorial conflicts, treaties, and political accessions, the Neo-Babylonian empire underwent an unsustainable and rapid time of prosperity and security. The fear and terror that Babylon brought upon the Mediterranean nation’s conformance to the interests of King Nebuchadnezzar II that would pass away after his death.13 The root of Neo-Babylonian’s meteoric rise was Nebuchadnezzar by the will and control of Yahweh. As confessed by Nebuchadnezzar, it was Yahweh who does according to His will. The King of Babylon recognized that Yahweh, “the Most High” and “King of Heaven,” was in control and produced the events and circumstances brought about through Babylon (Dan. 4:34-37). Through the counsel and interpretive work of the prophet Daniel, King Nebuchadnezzar came to recognize that the purpose of the empire’s existence was to serve as an instrument of punishment and justice upon the nations while functioning as a generational host to Judah.

Society

If not purely through the prophet Daniel’s encounters with Nebuchadnezzar, the people of exiled Judah knew why the Neo-Babylonian empire came to exist. Babylon wielded power and strength to judge Judah, and the nations, it all originated from Yahweh, and they knew it. This perspective while Judah was away from their homeland added weight to their interpersonal circumstances among the Babylonians. The reality was, exiled Judah came to understand in advance that their captors were temporarily in their position of authority and supremacy. Because of the kingdoms to follow, empires would rise and fall to bring about the redemptive will of Yahweh according to the prophetic voice of Daniel. Nebuchadnezzar’s kingdom was among the first to set the world stage for the rise and fall of Assyria, Babylon, Persia, Greece, Rome, and others down through the centuries.

Until then, in the daily lives of the Jews in Babylon, they were immersed in the culture and social norms of the Mesopotamian people. At the same time, the people of Judah retained their faith, life, and traditions to honor their cherished values and ancestors.14 In general, life in the diaspora appeared bleak after the fall of Jerusalem and the exile of Judah to Babylon. The mindset of the Jews was certain to echo back to the time of Egyptian captivity, then to Assyria, and now to Babylon. To contemplate among themselves, would they ever learn and abide in Yahweh even if it were necessary to return to Him when they fall away or out of fellowship with Him. The body of Judah during and after their time in Babylon had some soul searching to do, especially in light of the evil behaviors of the historical judges that preceded them. They were sure to have a reputation among the Babylonian people and to the Mesopotamian population at large.

Culture, Politics, and Religion

It was usual for nations, kingdoms, or empires to appoint rulers and governors over vassal territories to assure sovereign continuity. To minimize conflicts of interest and maximize the likelihood of cooperation and loyalty, Nebuchadnezzar named successors to rulers, stewards, and governors of the vassal areas of Judea and Jerusalem. Just as Egypt had done before the Babylonian conquest, Pharoah Neco appointed Eliakim, given the name Jehoiakim, over Judah to serve from 609-598 B.C.15 Afterward, Jehoiakim was replaced by his son, Jehoiachin, an evil king, also known as Jeconiah (2 Chr. 36:9). Once the replacement king was confronted by Nebuchadnezzar and deported to Babylon, he was promptly replaced by Mattaniah, with an assigned name Zedekiah, under terms of an agreement in loyalty to Babylon.16

While the city of Babylon itself was sure to have its form of government under the kingship of Nebuchadnezzar, the Neo-Babylonian empire consisted of appointed or accepted rulers who were obligated to abide by terms that assured their well-being. To fund its projects, military, and infrastructure, it was necessary to keep tribute currencies and resources flowing to the Babylonian empire while securing ongoing allegiance even if under duress or threat of destruction and removal. The political conditions at the time were not merely in competition for resources or power to make policy and govern but to survive by cooperation and legal adherence to Babylonian requirements.

The social order of Babylon was held together by its veneration of Marduk. The foreign god, to the Jews, was recognized as the supreme ruler of the Mesopotamian universe.

Marduk was the god of Babylon.17 The people of Babylon associated Marduk as a political deity who was a storm god responsible for the delivery of rain and vegetation growth. From the pantheon of Old Babylonian tradition, Marduk became an amalgam of other gods as he attained their features as a form of lasting supremacy. The priests of Babylon linked Marduk to significant god activity and were akin to the god Baal of the Canaanites. Just as Baal was the storm god of the Canaanites,18 Marduk was the storm god of the Babylonians. Both were associated with the Baal cycle of Mesopotamian religious tradition.

The worship and prayer of the Babylonian people were directed to Marduk as a patron deity. Beneficial outcomes were expected from the god as a bartering matter to fulfill the needs of the people in support of water, vegetation, and agriculture. Art, gatherings, theater, education, and other cultural functions often centered around Marduk as a form of honor and community. The Babylonian people directed their hopes and aspirations to their god, Marduk.

Law and Trade

The range and methods of monetary revenue sources and barter came in the form of taxation (tribute) and redistribution of currency through labor and projects by which constructed materials were involved. The sale of primitive goods and services was abundant in support of public and private livelihoods of persons who would offer their competencies and materials. For example, stone workers, woodworkers, and carriages were typical occupations. Babylonian temples were a form of brothels as prostitutes accepted offerings from visitors or worshipers.19

Social order was often held together by a mixed and subjective type of “justice” stemming from the preferences of Nebuchadnezzar or by his decrees borne from the counsel of his officials. For example, Nebuchadnezzar “passed sentence” upon Zedekiah (Jer.52:9, 11), the last king of Judah, when he broke his sworn loyalty oath.20 In this instance and others, Nebuchadnezzar was a vicious and brutal judge and executioner without any sense of mercy whatsoever to temper the perceptions of the Babylonian citizenry. Nebuchadnezzars’ absurdity of justice was further highlighted by the incident in which he was enraged because Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego would not bow before his constructed statue set before them (Dan. 3:8-29). While the three who were subjected to the furnace, in the cause of justice, were miraculously unharmed, Nebuchadnezzar’s officials herald a legal proclamation with an explicit penalty of death bearing no objection from the King (Dan. 3:4-6).

While Nebuchadnezzar was a brilliant military commander capable of putting nations to the sword, he was an accomplished practitioner of torture and violence. All while reigning as the king of the Neo-Babylonian empire, he was fecklessly inept when it came to the justice of his people, namely the subjects of Babylon at all levels. The façade of beauty, wealth, and splendor of his empire was paper-thin by its structures, assets, and looted treasures displaced by the judgments of Yahweh. The empire, as it was meant to be, was temporal with a termination date. As the king was unpredictable and inconsistent with maintaining order within his kingdom, the Neo-Babylonian empire was secured yet unstable. It was sure to fall once he was deceased eventually. His platitudes and acknowledgments about Yahweh as Most High were only meaningful insofar as an admission before the gods and his people that Yahweh is God.

Conclusion

When taking a long and careful look at the historical reality of the Neo-Babylonian empire, one might see the mystique or intriguing nature of its place in time. Its feats, accomplishments, and innovative contributions to following generations are a false weight of comparison to that which it was. The Neo-Babylonian empire was an exceedingly evil and profane place in which the people of Judea were to reside for a fixed duration of 70-years. By the very covenant violations that got Judah into severe trouble, idolatry, and injustice, they were further steeped in it during their time of exile. As Judah was instructed to muster normalcy, the people of God were to endure their exile until their liberation before the Neo-Babylonian empire’s destruction in 539 B.C., by Yahweh, through the hands of King Cyrus the Great of Persia.21

Citations

1 Daniel J. Hays, Tremper Longman III, ed., The Message of the Prophets. A Survey of the Prophetic and Apocalyptic Books of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2010), 64-67.

2 Eugene H. Merrill, Kingdom of Priests: A History of Old Testament Israel, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008), 46.

3 Charles H. Dyer, “Jeremiah,” in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: An Exposition of the Scriptures, ed. J. F. Walvoord and R. B. Zuck, vol. 1 (Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1985), 1125.

4 John D. Barry et al. Faithlife Study Bible. “Neo-Babylonian Empire Timeline Infographic” (Bellingham: Lexham Press, 2012).

5 Rose Book of Bible & Christian History Timelines, More than 6000 years at a glance (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2006), 7.

6 Ibid. Merrill, 503.

7 Michael A. Grisanti, “History of the Covenant People Course Notes” (unpublished course notes, TMU, 2018), 140.

8 James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd ed. with Supplement (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 321.

9 Jack R. Lundbom, “Builders of Ancient Babylon: Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II,” Journal of Bible and Theology, Vol.7 (2017), 160.

10 James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd ed. with Supplement. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 563.

11 D. J. Wiseman, “Babylonia,” ed. D. R. W. Wood et al., New Bible Dictionary (Leicester, England; Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 115.

12 Rainer Albertz, Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003), 439.

13 David Helm, Daniel for You, ed. Carl Laferton (Surrey: The Good Book Company, 2015), 38-39.

14 Eugene H. Merrill, Kingdom of Priests: A History of Old Testament Israel, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008), 484.

15 Tremper Longman III, Raymond B. Dillard. An Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006), 324.

16 Andrew E. Hill. “Jehoiachin,” Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1988), 1102.

17 Tzvi Abusch, “Marduk,” ed. Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. van der Horst, Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (Leiden; Boston; Köln; Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge: Brill; Eerdmans, 1999), 543.

18 James R. Battenfield, “YHWH’s Refutation of the Baal Myth through the Actions of Elijah and Elisha,” in Israel’s Apostasy and Restoration Essays in Honor of Roland K. Harrison, edited by Avraham Gileadi (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1988), 26.

19 Mark W. Chavalas, “Herodotus and Babylonian Women,” in Conversations with the Biblical World, Vol. 35 (2015), 22 (Leiden; Boston; Köln; Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge: Brill; Eerdmans, 1999), 34.

20 Peter Coxon, “Nebuchadnezzar’s Hermeneutical Dilemma,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, Vol. 66 (1995), 92.

21 Debra Reid, Martin H. Manser, Who’s Who of the Bible: Everything You Need to Know about Everyone Named in the Bible. Prod. Logos Systems Inc.(Oxford, England: Lion Books, 2013).

Bibliography

Abusch, Tzvi. Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. 2nd. Edited by Bob Becking, Peter W. van der Horst Karel van der Toorn. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 1998.

Albertz, Rainer. Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003.

Archer, Gleason L. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction. Chicago: Moody, 2007.

Chavalas, Mark W. “Herodotus and Babylonian Women.” Conversations with the Biblical World 35, 2015: 22-52.

Coxon, Peter. “Nebuchadnezzar’s Hermeneutical Dilemma.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 1995: 87-97.

Debra Reid, Martin H. Manser. Who’s Who of the Bible: Everything You Need to Know about Everyone Named in the Bible. Prod. Logos Systems Inc. Oxford: Lion Books, 2013.

Grisanti, Michael A. History of the Covenant People, Course Notes. Santa Clarita, 06 02, 2021.

Hays, J. Daniel, and Tremper Longman III. ed., The Message of the Prophets. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2010.

Helm, David. Daniel for You. Edited by Carl Laferton. Surrey: The Good Book Company, 2015.

Hill, Andrew E. Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1988.

James Bennett Pritchard, ed. The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd ed. with Supplement. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969.

Koehler, Ludwig. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. Edited by M.E.J. Richardson. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2000.

Lundbom, Jack R. “Builders of Ancient Babylon: Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II.” A Journal of Bible and Theology, 2017: 154-166.

Merrill, Eugene H. Kingdom of Priests: A History of Old Testament Israel. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

Rose Publishing; Illustrated edition. Rose Book of Bible & Christian History Time Lines. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2006.

Tremper Longman III, Raymond B. Dillard. An Introduction to the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006.

Walvoord, John F., Zuck, Roy B. The Bible Knowledge Commentary. Wheaton: Victor Books, 1985.

Wiseman, D.J. Babylonia, New Bible Dictionary. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1996.