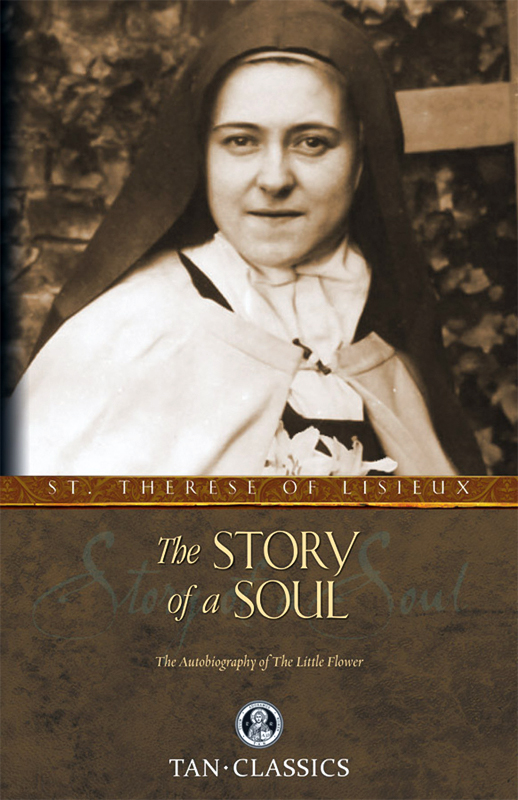

“Story of a Soul” (“L’Histoire d’une Âme”) is an autobiographical work by St. Thérèse of Lisieux (Marie Françoise-Thérèse Martin), a Carmelite nun and one of the most venerated figures in modern Catholicism. Thérèse The book was published posthumously in 1898, a year after her death from tuberculosis at the age of 24.

Thérèse was born on January 2, 1873, in Alençon, France, and passed away on September 30, 1897, in Lisieux, France. Compiled from manuscripts she left behind, her spiritual autobiography aims to present the ‘little way’ of Thérèse, a path to God through simplicity, humility, and a boundless trust in divine providence. This book is about the story of a little flower. A saint of the little way.

Background

Contents

Early Life and Family

Therese’s autobiography begins with an account of her early life, born to deeply devout parents in Alençon, France. She describes the religiosity of her family, her mother’s untimely death when Thérèse was just four years old, and her father’s subsequent move with the family to Lisieux. She expounds upon the deep impression her mother’s death left on her, turning her into a hypersensitive and emotionally delicate child. She is subsequently raised by her older sisters and father, who become key figures in her spiritual formation and development.

Louis Martin – Father

Louis Martin was born in Bordeaux, France, in 1823. He was a watchmaker by trade but also had a deep interest in religious life. In fact, earlier in his life, Louis aspired to become a monk, specifically an Augustinian monk, but this ambition was set aside due to his lack of proficiency in Latin, a prerequisite for monastic life during that time. Despite this, his devout Catholicism remained an integral part of his identity. Louis was a third-order lay Franciscan, meaning that he committed himself to living out the values and spiritual practices of the Franciscan order while remaining a layperson.

Zélie Guérin – Mother

Zélie Guérin was born in 1831 in Saint-Denis-sur-Sarthon, Orne, France. She too initially felt a call to religious life but was advised against it. Instead, she trained as a lacemaker and started her own business. Zélie was deeply spiritual, attending Mass daily and offering her work up as a form of prayer. She belonged to the Third Order of Mount Carmel, a lay confraternity attached to the Carmelite order.

Louis and Zélie met in 1858 and were married just three months later. They initially decided to live as “brother and sister” in a continent marriage, dedicating themselves to religious practices. However, a spiritual director advised them to have children for the glory of God, and they heeded this advice. Their union was not merely a social contract but a spiritual alliance, designed to nurture the faith within the family structure.

The couple had nine children, four of whom died in infancy. Both Louis and Zélie were deeply affected by the deaths of their young children, but they saw even these tragic events as opportunities for spiritual growth, offering their suffering as a sacrifice to God. In 1877, Zélie died of breast cancer, leaving Louis to raise their five surviving daughters. He moved the family to Lisieux to be closer to Zélie’s brother and his wife, who helped him with the children. Louis himself suffered from a series of strokes and was afflicted with cerebral arteriosclerosis, eventually leading to his death in 1894.

The exemplary faith of Louis and Zélie was officially recognized by the Catholic Church when they were canonized as saints by Pope Francis on October 18, 2015. They are the first married couple to be canonized together.

Marie – Sister

The eldest sister, Marie, assumed a maternal role for her younger sisters after their mother’s death. She was deeply religious and was the first among the sisters to enter the Carmelite convent in Lisieux. She was a formative influence on Thérèse’s understanding of religious life.

Pauline – Sister

Pauline essentially became Thérèse’s surrogate mother after Zélie’s death. It was Pauline who first nurtured Thérèse’s desire for a religious vocation. She entered the Carmelite convent before Thérèse and was later elected as Prioress, taking the name Mother Agnes of Jesus.

Léonie – Sister

Léonie was the least healthy of the Martin children and had a more difficult temperament. Despite facing multiple obstacles in her pursuit of religious life, she eventually became a nun in the Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary, taking the name Sister Françoise-Thérèse. She has been declared a Servant of God, the first stage in the process of canonization.

Céline – Sister

The sister closest in age to Thérèse, Céline played a significant role in popularizing Thérèse’s message after her death. She became a Carmelite nun like her sisters, taking the name Sister Geneviève of the Holy Face. She was the one who initially compiled and edited Thérèse’s writings, contributing greatly to her sister’s posthumous fame. The religious devotion of the Martin family deeply influenced Thérèse’s spiritual life, providing a living example of collective holiness and individual commitment to God. The family’s spirituality was rooted in daily prayer, attendance at Mass, and acts of charity, all of which were foundational in forming Thérèse’s approach to faith. This exceptional familial context forms an important backdrop to Thérèse’s own journey, which she elaborated upon in her spiritual autobiography. The Martin family thus serves as a compelling testament to the potential for deep spirituality and sanctity within the context of family life.

Childhood Conversion

A significant part of the book covers her childhood and adolescent years, where she narrates her First Communion, her eldest sister Marie’s death, and her miraculous healing from an unknown illness. Her account of Christmas Eve was most impactful when she was 14 years old. Thérèse describes this event as her “complete conversion,” when she overcomes her oversensitivity and adopts a more mature, stoic attitude, attributing this change to God’s grace.

Carmelite Life

Thérèse recounts her relentless pursuit to enter the Carmelite convent at an unusually young age of 15, overcoming numerous obstacles including her father’s initial reluctance and the Church’s age restrictions. She describes her joy at entering the cloister and her subsequent life as a nun. Despite the ascetic lifestyle and the rigors of convent life, she emphasizes her joy and contentment in serving the Lord. She writes about the challenges she faces, including her struggle with prayer and the deaths of her father and several close sisters, framing each challenge as an opportunity for spiritual growth.

The Carmelite convent in Lisieux where Saint Thérèse of Lisieux spent her religious life was home to various nuns who played significant roles in her spiritual development and daily life. It’s crucial to recognize that the Carmelite environment was designed to be a setting of intense spiritual discipline and communal living. This backdrop provided a fertile ground for Thérèse’s spiritual growth and her development of the “little way.” Here are some of the key figures in the convent during Thérèse’s time:

Pauline (Mother Agnes of Jesus) was Thérèse’s second eldest sister and became her surrogate mother after their mother’s death. She entered the Carmelite convent before Thérèse did, and her spiritual life significantly influenced her younger sister. When she became prioress, she allowed Thérèse to write her autobiography.

Marie (Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart), the eldest sister, also joined the Carmelite convent in Lisieux. After their mother’s passing, she assumed a maternal role and later took a significant role in the convent life. Her spiritual steadiness and maternal instincts often offered emotional and religious support to Thérèse.

Céline (Sister Geneviève of the Holy Face), closest in age to Thérèse, joined her sisters in the convent a few years after Thérèse’s entrance. Céline’s entrance into the Carmel was something Thérèse ardently prayed for. Céline later became instrumental in disseminating Thérèse’s teachings and compiling her writings. Marie de Gonzague, who was the Prioress of the Carmelite convent in Lisieux during part of Saint Thérèse’s time there, initially objected to Céline (Sister Geneviève of the Holy Face) entering the convent. Marie was a complex figure with a strong personality and had significant influence within the Carmelite community.

Marie de Gonzague was concerned about the growing influence of the Martin family within the convent. When Céline wished to enter, two of her sisters, Marie (Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart) and Pauline (Mother Agnes of Jesus), were already in the Carmel, along with Thérèse herself. The addition of another Martin sister was viewed as potentially problematic, raising questions about nepotism and family influence within a Catholic community that valued detachment from worldly relationships, even familial ones.

This hesitation on Marie’s part was not entirely without basis, given the structure and values of Carmelite life. Carmelites are expected to relinquish worldly attachments to pursue a life of contemplation and union with God more freely. Having many biological relatives in the same religious community could be seen as a challenge to this ideal of detachment. However, Thérèse ardently prayed for Céline’s entrance into the Carmel, seeing it as a means of spiritual support and communal growth. Thérèse’s deep spiritual insight and the apparent sincerity and vocation of Céline eventually overcame the objections. Céline entered the Carmelite convent in Lisieux in 1894, shortly after their father Louis Martin’s death. After her entrance, Céline became an integral part of the religious community and was pivotal in promoting Thérèse’s spiritual legacy after her death, including disseminating Therese’s autobiography.

The episode involving Marie de Gonzague’s objection to Céline’s entrance underscores the complexities of religious life, where spiritual ideals often intersect with human concerns and limitations. It also serves as a testament to the strength of Thérèse’s faith and the depth of her understanding of religious vocation—not as an escape from human relationships but as a transformation of them in the light of divine love. Marie de Gonzague was the prioress when Thérèse entered the Carmel and was a significant figure in Thérèse’s early years at the convent. Her leadership style was sometimes a subject of internal difficulty for Thérèse, as Marie had a complex personality and could be both affectionate and stern. However, Thérèse saw these challenges as an opportunity for spiritual growth.

Sister Marie of the Angels was a close friend of Thérèse within the convent, and she was drawn to Thérèse’s spirituality and became one of her confidantes. Thérèse in turn saw in her a soul that was naturally inclined toward friendship and emotional closeness.

Sister Saint Vincent de Paul was the novice mistress when Thérèse entered the convent. While she was strict and very traditional, her role was crucial as she was responsible for the initial religious formation of the novices, including Thérèse.

Sister Marie-Philomène had a difficult personality and was one of the sisters Thérèse found challenging to live with. Nonetheless, she became a catalyst for Thérèse’s practice of her “little way,” turning daily irritations into opportunities for demonstrating love and forbearance.

Besides the mentioned figures, the Carmelite community was composed of other sisters whose names might not be as prominently remembered but who nonetheless constituted the living, breathing community of faith that shaped Thérèse’s religious experience. These nuns lived lives of prayer, penance, and seclusion, in adherence to the Rule of Carmel.

While Thérèse’s interactions with these individuals ranged from close kinship to challenging trials, each relationship played a distinct role in her spiritual journey. The nuns, who shared her daily life, indirectly or directly contributed to shaping her “little way” of spiritual childhood, a simple yet profound path to holiness through daily acts of love and sacrifice. The collective spirituality of the Carmelite community in Lisieux was characterized by its emphasis on contemplative prayer and strict adherence to the Rule of Carmel, influenced by the writings of earlier Carmelites like St. Teresa of Ávila and St. John of the Cross. In this context, Thérèse developed her theology of the “little way,” which, although deeply personal, was also a product of her communal experience of monastic life.

Childhood Sufferings

Saint Thérèse faced a series of trials and tribulations in her early life that significantly shaped her spiritual journey. She was the youngest of nine children, four of whom died in infancy. Her family was deeply religious, anchored by her parents, Louis Martin and Zélie Guérin, who are now canonized saints. Despite the family’s devotion, or perhaps because of it, Thérèse’s early life was marked by an array of sufferings that involved separation, illness, and emotional turbulence.

Loss of Therese’s Mother

The first profound suffering that touched her life was the death of her mother, Zélie, from breast cancer when Thérèse was just four and a half years old. This loss created a void in her life, thrusting her into an early confrontation with the transient nature of human existence. The absence of maternal love became an overarching theme in her early years, contributing to her heightened sensitivity and need for affection.

Move to Lisieux

After Zélie’s death, the family moved to Lisieux to be closer to Zélie’s brother and his wife, who helped to look after the children. While this move provided some social and familial support, the absence of Thérèse’s mother became more palpable. Her father, Louis, although a loving parent, was often absorbed in his own grief and devotion, rendering him less emotionally available. Thérèse grew especially close to her sister Pauline, who became a surrogate mother to her. However, this attachment would also be a source of suffering when Pauline entered the Carmelite convent, leaving Thérèse feeling abandoned once more.

Illness and Suffering

Thérèse was often sickly as a child, and her health was a constant concern for the family. She contracted illnesses easily and also showed signs of emotional fragility. This emotional sensitivity was exacerbated by her perceived abandonment, first by her mother’s death and then by Pauline’s departure for the convent. Thérèse even experienced a debilitating nervous malady that confined her to bed for an extended period. Some biographers and spiritual writers have posited that this illness had both psychological and spiritual dimensions, marking a crisis point in her early spiritual development.

School and Scruples

School was another area of suffering for Thérèse. Due to her fragile health and emotional state, she initially received education at home. When she did enter public schooling, she was subject to ridicule and misunderstanding, partly because of her intense religiosity and shyness. She also went through a period of scrupulosity, a kind of religious OCD where she became overly concerned about the state of her soul and the morality of her actions, even when such concerns were objectively baseless. This was a form of spiritual suffering that further isolated her from her peers and added layers of internal strife.

The “Christmas Conversion”

The culmination of her early sufferings could be said to have occurred in what Thérèse described as her “Christmas conversion” at the age of 13. On Christmas Eve in 1886, after Mass, she overheard her father express annoyance at her lingering habit of expecting Christmas presents despite her growing age. Instead of responding with hurt or resentment, she experienced a sudden and profound inner transformation. The event served as a spiritual milestone where she felt herself fortified with new courage and resolve, freeing her from her excessive sensitivities and initiating a more mature phase of her spiritual life. The early life of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux was a crucible of various forms of suffering: the loss of a mother, separation from beloved siblings, physical and emotional illnesses, and spiritual anxieties. However, Each of these trials played a crucial role in shaping her spirituality and understanding of God’s love and providence. These early experiences of suffering provided her with the spiritual raw material that would later crystallize into her “little way” — a spiritual path marked by complete trust in God’s mercy and a commitment to doing small things with great love.

Formative Years

After her Christmas encounter, Thérèse’s commitment to her spiritual life deepened significantly. She became more engaged in practices of prayer, attending daily Mass, and reading spiritual books. Particularly influential were the works of St. John of the Cross, whose writings on the Dark Night of the Soul resonated deeply with her own experience of spiritual and emotional suffering. She also found herself more inclined toward self-sacrifice and small acts of charity, be it within the family context or within her broader social interactions.

The Pilgrimage to Rome

In 1887, at age 14, Thérèse embarked on a pilgrimage to Rome with her father Louis and sister Céline. This pilgrimage was transformative for her in several ways. First, it broadened her horizons beyond the sheltered environment of Lisieux. Second, it served as a testing ground for her emerging spiritual maturity. She showed remarkable self-discipline and poise during the trip, embracing the challenges and discomforts of the journey as offerings to God. Most significantly, during a papal audience with Pope Leo XIII, Thérèse asked the Pope’s permission to enter the Carmelite convent at an early age. While she did not receive a definitive answer, the Pope’s gentle response of “Well, my child, do what the superiors decide…” gave her some distress and uncertainty because her Superiors did not favor joining the convent at an early age. However, with the hope of Leo XIII’s assurance that God’s will shall be done by declaring, “Well, well! You will enter if it is God’s Will,“ her passion for entering the convent didn’t diminish, even with the disappointment of no immediate consent.

Preparations for Carmel

Upon her return from Rome, Thérèse faced administrative and familial obstacles to her desired early entrance into the convent. The local bishop initially hesitated to permit her entry at such a young age, and her uncle opposed the idea, citing her youth and fragility. Yet Thérèse remained steadfast in her commitment and continued her spiritual preparations for religious life. During this period, she lived a quasi-monastic life at home, further deepening her life of prayer and ascetic practices.

Entry into the Convent

Finally, in April 1888, at age 15, Thérèse’s request was granted, and she entered the Carmelite convent in Lisieux. This was a triumphant moment for her but also a bittersweet one, as it meant leaving behind her father, who had been a source of strength and support, and her sister Céline, who was her confidante and close friend.

So, the adolescent years of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux were marked by significant spiritual milestones that laid the groundwork for her later contributions to Christian spirituality. Her conversion heralded a newfound emotional and spiritual maturity, her pilgrimage to Rome solidified her vocation, and her final preparations and entry into the Carmelite convent realized her dream of a life devoted entirely to God. These years were a time of personal spiritual deepening and externalizing her interior life through acts of love, sacrifice, and courage, encapsulating the essential elements of her “little way.”

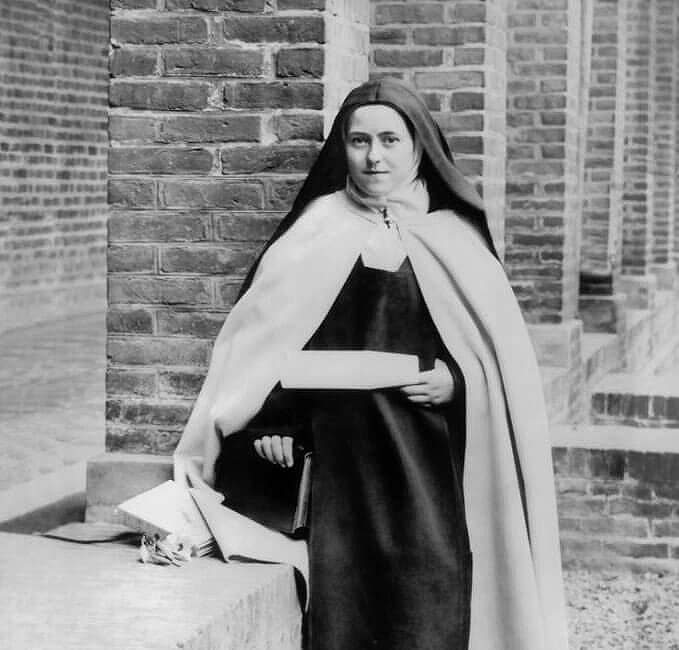

After her pilgrimage to Rome and subsequent petitioning of ecclesiastical authorities, Saint Thérèse of Lisieux entered the Carmelite convent in Lisieux, France, in April 1888 at the age of 15. Her time at the Carmel was marked by deep spiritual insights, growth, trials, and the development of her seminal concept known as the “little way.” Her life in the convent provides a glimpse into an interior world rich in spiritual experience but not devoid of hardship and suffering.

Adaptation and Challenges

Thérèse was initially received into the convent as a postulant and lived through the period of initial formation under the guidance of her novice mistress, Marie de Gonzague. Adapting to the austere Carmelite way of life challenged the young Thérèse. Nevertheless, her profound faith and sense of vocation propelled her to embrace the monastic rigors with a courageous heart. Thérèse also had the unique experience of being in the same convent as two of her older sisters, Pauline (Mother Agnes of Jesus) and Marie (Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart). On January 10, 1889, Thérèse officially became a novice, a period meant for more intense religious training and discernment. She took the religious name, Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face, reflecting her devotion. On September 8, 1890, Thérèse made her religious profession, solidifying her commitment to a life of poverty and obedience.

The Community and Superiors

Thérèse lived under the authority of several prioresses during her time in Carmel, including Mother Marie de Gonzague and her own sister, Pauline (Mother Agnes). Her relationship with her superiors was complex. While deeply respecting authority, she occasionally experienced different perspectives, particularly with Mother Marie de Gonzague. Despite this, Thérèse maintained her vow of obedience and carried out all tasks assigned to her, however menial or difficult they were.

The Little Way

It was during her time in Carmel that Thérèse’s view of the “little way” fully matured. Through her daily duties, personal reflections, and experiences of limitation and imperfection, Thérèse developed a spiritual approach that focused on small, everyday acts of love and kindness. In a community where all were striving for perfection and holiness, Thérèse’s “little way” was somewhat unconventional. She believed that one did not have to perform grand acts to achieve holiness; rather, it was about doing the smallest tasks with great love and surrendering all to God’s mercy. The ‘little way’ encourages souls to seek sanctity through simple acts of love and devotion, always performed with the utmost sincerity. Thérèse sees every act, no matter how mundane, as an opportunity to express love for God. She emphasizes the importance of humility, advocating for acceptance of one’s weaknesses and shortcomings as a path to divine grace.

Saint Thérèse of Lisieux’s concept of the “little way” was communicated to various members of her Carmelite community, including Mother Marie de Gonzague. The “little way” is a spiritual path characterized by humility, simplicity, and childlike trust in God. Although Thérèse articulated her spiritual insights in various contexts, including her autobiography, her letters, and her last conversations, the essence remains the same: an approach to holiness accessible to anyone, irrespective of their state in life, by doing small acts with great love and by fully trusting in God’s merciful love.

Thérèse’s relationship with Mother Marie de Gonzague was complex. While Mother Marie was a superior whom Thérèse obeyed and respected, there were times when their views on spiritual matters diverged. Nevertheless, Thérèse tried to communicate her idea of the “little way” as a means to make spiritual progress through life’s mundane and ordinary circumstances.

Thérèse conveyed that holiness did not necessarily require grandiose acts or severe penances, which were often the hallmarks of spiritual rigor in the Carmelite tradition influenced by St. John of the Cross and St. Teresa of Ávila. Rather, Thérèse emphasized that everyday acts, performed with love and a spirit of surrender to God’s will, could lead one to sanctity. Thérèse compared herself to a little child who knew that she could not ascend the staircase of heaven in one go. Instead, she would lift her arms and allow God, her heavenly Father, to pick her up.

This approach to spirituality was particularly poignant given the strict, penitential regimen of the Carmelite Order, which emphasized detachment, mortification, and deep contemplative prayer. Thérèse’s “little way” provided an alternative route to pleasing God, one that was accessible for any soul genuinely seeking union with the divine but perhaps overwhelmed by the daunting ascetic practices traditionally associated with Carmelite spirituality.

| Day of Grace [2] | Date |

|---|---|

| Birthday | January 2, 1873 |

| Baptism | January 4, 1873 |

| The Smile of Our Lady | May 10, 1883 |

| First Communion | May 8, 1884 |

| Confirmation | June 14, 1884 |

| Conversion | December 25, 1886 |

| Audience with Leo XIII | November 20, 1887 |

| Entry into the Carmel | April 9, 1888 |

| Clothing | January 10, 1889 |

| Profession | September 8, 1890 |

| Taking of the Veil | September 24, 1890 |

| Act of Oblation | June 9, 1895 |

| Entry into Heaven | September 30, 1897 |

The “little way” is a theology grounded in the New Testament, particularly in Christ’s exhortation to become like little children to enter the Kingdom of Heaven (Matthew 18:3). Its persuasion lies in its transformative simplicity: turning each moment into an opportunity for grace. Each annoyance, inconvenience, or disappointment could become a “little” offering to God. Moreover, recognizing one’s “littleness,” one’s shortcomings, and inability to be perfect leads to a fuller reliance on God’s grace and mercy.

While Marie de Gonzague had initial reservations about Céline entering the convent, possibly due to the fear of familial attachments undermining monastic detachment, Thérèse’s spirituality was in many ways an affirmation of authentic Carmelite ideals: complete surrender to God and the pursuit of divine love in every aspect of life. Although Thérèse’s “little way” did not initially gain universal acceptance within her own community, including among leaders like Marie de Gonzague, it has since been recognized as a profound expression of Christian doctrine, resulting in Thérèse being declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope John Paul II in 1997.

The “little way” as expressed to Marie de Gonzague and others, is a radical reorientation of spiritual life, focusing not on the grandeur of our actions but on the grandeur of God’s merciful love, to which we respond through simple, humble acts carried out with great love.

Vow & Act of Oblation

St. Thérèse of Lisieux, born Marie Françoise-Thérèse Martin, took a vow of “offering herself to Merciful Love” before composing her Act of Oblation to Merciful Love. The vow can be seen as a prelude or preliminary commitment that prepared her for the more elaborate and profound Act of Oblation. This vow was a personal spiritual commitment, made in the context of her Carmelite life, to offer herself entirely to the love and mercy of God. Unlike standard religious vows of poverty and obedience, which she would have taken upon entering the Carmelite order, this vow was a private one meant to deepen her relationship with God.

In taking this vow, St. Thérèse sought to become a living sacrifice to God’s merciful love, aiming to love God as He had loved her, even in her littleness and imperfections. The vow signified her total surrender to Divine Providence, an abandonment that aimed to empty her of self-love and self-will as she poured out further to love God more fully. It was a way of responding to the ineffable love she believed God had shown her, despite her unworthiness.

The vow was an extension of her “little way,” a path of spiritual childhood that emphasizes humility, simplicity, and complete trust in God. The “little way” was a theology of spiritual advancement and a disposition of the religious life, as she often discussed it in terms of spiritual childhood and the abandonment of self-will in favor of Divine Will. She believed that, like a child, she had to trust completely in God, who is all-loving and all-powerful.

St. Thérèse was greatly influenced by both the Old and New Testaments. Her theology was deeply rooted in the Bible, and she often cited various passages in her writings, notably from the Psalms and the Song of Solomon, as well as the New Testament letters and Gospels, to support her spiritual insights. Her commitment to the vow and her subsequent Act of Oblation can be viewed as a lasting effort by faith to live out Jesus Christ’s commandment of love as recorded in the Gospels (e.g., Matthew 22:37-40; John 13:34-35).

St. Thérèse’s Vow

“O Jesus, my Divine Spouse, grant that my baptismal robe may never be sullied. Take me from this world rather than let me stain my soul by committing the least wilful fault. May I never seek or find aught but Thee alone! May all creatures be nothing to me and I nothing to them! May no earthly thing disturb my peace!

“O Jesus, I ask but Peace.… Peace, and above all, Love.… Love—without limit. Jesus, I ask that for Thy sake I may die a Martyr; give me martyrdom of soul or body. Or rather give me both the one and the other. “Grant that I may fulfill my engagements in all their perfection; that no one may think of me; that I may be trodden underfoot, forgotten, as a little grain of sand. I offer myself to Thee, O my Beloved, that Thou mayest ever perfectly accomplish in me Thy Holy Will, without let or hindrance from creatures.”

September 8, 1890

Oblation means “the act of offering; an instance of offering” and, by extension, “the thing offered.” It is a term that refers to a solemn offering, sacrifice, or presentation to God, to the Church for use in God’s service, or to the faithful, such as giving alms to the poor. The Oblation to Merciful Love is one of the most significant aspects of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux’s spiritual legacy. It stands as a defining moment in her life and a crystallization of her theology, encapsulating the essence of her “little way.” The act of oblation took place on June 9, 1895, during the Solemnity of the Most Holy Trinity, and was an outpouring of her deepest spiritual convictions and aspirations.

By 1895, Thérèse had been in the Carmelite convent for seven years and had matured significantly in her understanding of God’s merciful love. She was influenced by the writings of St. John of the Cross and the teachings of the Church, but her own lived experiences of faith, hope, and charity prepared her for the Oblation. She had been grappling with the enormity of God’s love and the smallness of her own being, contemplating how she could possibly hope to love God in the way He deserved to be loved. These profound reflections would find their culmination in the Oblation.

On an especially significant Trinity Sunday, Thérèse was in the chapel with her Carmelite sisters. As the liturgy unfolded, she felt an overpowering sense of God’s presence and merciful love. Inspired by this experience and the readings of the day, she took pen and paper and wrote down her ‘Act of Oblation to Merciful Love.’ It was a prayer, but more than that, it was an offering of herself as a holocaust to God’s merciful love.

In her text, she offered herself unreservedly to God, not in the context of justice or privilege, but in the context of mercy. Thérèse acknowledged her own littleness and the impossibility of her making a worthy offering of love to God. Therefore, she asked Jesus to “drown her in Himself” so that she could become a conduit of His love. She expressed a desire for her oblation to be an act of praise, an acknowledgment of God’s all-encompassing love that takes even the smallest offerings and turns them into something grand. Importantly, she committed to letting this love shine through her in acts of kindness, patience, and humility, thereby allowing others to experience God’s love through her.

The Oblation is steeped in a rich theological vision. It embodies a theology of surrender, where Thérèse gives herself fully to the will of God. It also echoes the idea of divine filiation, as she sees herself as a child of God, relying entirely on His mercy and benevolence. Furthermore, it encapsulates her understanding of the redemptive power of suffering, as she offers not only her joys but also her sorrows for the salvation of souls. In essence, the Oblation is a bold act of faith, reiterating her belief that God’s merciful love would accept her offering and magnify it for the sake of His greater glory despite her unworthiness.

This act was not a one-time event but rather a defining commitment that shaped the remainder of her life. Thérèse sought to live out her oblation in the daily activities and trials of her Carmelite existence, in her responsibilities as a sister and later as a novice mistress, and even in her intense suffering during her final illness.

The legacy of Thérèse’s Oblation to Merciful Love continues to impact many souls. Her written account of this spiritual milestone is often read and pondered upon by people from all walks of life, and many have made similar oblations inspired by her example. In a world often focused on deeds, self-glory, and achievements, the Oblation serves as a deeply meaningful statement of the transformative power of divine mercy and unwavering faith.

St. Thérèse’s Act of Oblation

“O my Divine Master,” I cried from the bottom of my heart, “shall Thy Justice alone receive victims of holocaust? Has not Thy Merciful Love also need thereof? On all sides it is ignored, rejected … the hearts on which Thou wouldst lavish it turn to creatures, there to seek their happiness in the miserable satisfaction of a moment, instead of casting themselves into Thine Arms, into the unfathomable furnace of Thine Infinite Love.

“O my God! Must Thy Love, which is disdained, lie hidden in Thy Heart? If Thou shouldst find souls offering themselves as victims of holocaust to Thy Love, Thou wouldst consume them rapidly; Thou wouldst be well pleased to suffer the flames of infinite tenderness to escape that are imprisoned in Thy Heart. “If Thy Justice—which is of earth—must needs be satisfied, how much more must Thy Merciful Love desire to inflame souls, since “Thy mercy reacheth even to the Heavens”? O Jesus! Let me be that happy victim—consume Thy holocaust with the Fire of Divine Love!”

June 9, 1895

Thérèse’s Oblation to Merciful Love is a deeply meaningful spiritual moment that epitomized her unique theology and spirituality. It was a profound offering of her complete self—body, soul, and will—to God’s boundless, merciful love. Through this act, Thérèse deepened her relationship with God and left a spiritual legacy that continues to inspire and guide people on their journey toward holiness.

Thérèse’s “Way of Love” is a profound spiritual pathway emphasizing humility, simplicity, and surrender to God’s Merciful Love. It challenges the conventional view that sanctity is reserved for the extraordinary and proclaims that the way to God is open to everyone in Christ through small acts performed with great love. Her spirituality remains a luminous example of Christian devotion, accessible and deeply rooted in the supremely authoritative teachings of the Bible. Her spirituality reflected the essence of the Gospel message—faith in God’s redemptive love and the call to love one’s neighbor. The Carmelite tradition, emphasizing contemplative prayer and mystical union with God, provided the means within which her spirituality grew.

Final Years & Legacy

In the final sections, the narrative turns poignant as Thérèse describes her painful battle with tuberculosis. Her suffering is severe, but she interprets it as a way to unite herself more closely with the suffering of Christ. During her illness, her spirituality matures even further, entering a state of great spiritual dryness that she endures with faith until her death.

“Story of a Soul” has profoundly impacted modern Catholic spirituality. Its widespread popularity led to her canonization by Pope Pius XI in 1925, and she was declared a Doctor of the Church in 1997, an honorific title given to individuals whose writings are deemed to have significantly impacted the formation of Christian doctrine. Thérèse’s emphasis on humility, simplicity, and love has resonated across denominational lines, becoming a source of inspiration for many beyond the confines of Catholicism.

The work engages with well-developed theological principles that resonate with Reformed and Orthodox traditions, particularly the truth of divine grace and the soul’s sanctification involving suffering and devotion. It also places a high premium on God’s Word, drawing extensively from scripture to elucidate Thérèse’s beliefs, thereby honoring the perspective of ‘Sola Scriptura,’ that the Bible is the ultimate authority in faith and practice.

Illness & Death

By 1894, Thérèse started experiencing symptoms of tuberculosis that would eventually lead to her death. Even as she faced physical deterioration, her spiritual depth seemed to grow, experiencing both a dark night of the soul—a period of spiritual dryness—and an intense closeness to God. During this time of deterioration, she was asked to write her autobiography, “The Story of a Soul,” at the behest of her sister Pauline, which later became one of the most widely read Catholic texts of modern times. Despite the hardships of illness, Thérèse took on the role of novice mistress in 1893, guiding younger nuns in their spiritual formation. Her counsel was marked by the same simplicity and love that characterized her spiritual path.

Thérèse’s health deteriorated rapidly in 1897, and she died on September 30 of the same year, at the young age of 24. In her final days, she faced extreme physical suffering and spiritual desolation but maintained her trust in God’s merciful love, offering her pains for the salvation of souls.

Legacy

The life and legacy of St. Thérèse of Lisieux stand as a testament to the enduring power of simplicity, humility, and love in the spiritual life. Born on January 2, 1873, in Alençon, France, Thérèse was the youngest of nine children in the Martin family, a devout Catholic household. She entered the Discalced Carmelites at the young age of 15 and died just nine years later from tuberculosis. Within her short life span, Thérèse left an indelible imprint on Christian spirituality that not only led to her canonization as a saint but also her designation as a Doctor of the Church—a rare and esteemed title that underscores the theological and spiritual depth of her writings.

Canonization

Thérèse’s canonization began remarkably quickly, reflecting her immediate impact on those who knew her and those who later read her autobiography. Ordinarily, the canonization process takes several decades, if not centuries, but in Thérèse’s case, the timeline was expedited. She died in 1897, and by 1914, Pope Pius X had already signed the decree for the introduction of her cause for beatification, the first step toward canonization.

In 1923, Thérèse was beatified, and just two years later, in 1925, she was canonized by Pope Pius XI. The speed of this process was unprecedented, partly because of the widespread distribution and influence of her autobiography but also due to the numerous reports of miracles attributed to her intercession. Her canonization was attended by a large international audience, attesting to the global impact she had already begun to make.

Influence and Impact

Thérèse’s influence is primarily grounded in her “little way,” a theology of spiritual childhood that emphasizes humility, simplicity, and complete trust in God. Unlike other paths to holiness that emphasize grand deeds, ascetic practices, or intense mystical experiences, Thérèse focused on everyday acts performed with love. This resonated with people from all walks of life, making her one of the most universally loved and revered saints.

Beyond the Catholic Church, Thérèse’s writings and spirituality have also found a home in various Christian denominations. Her “little way” has been seen as a practical application of the Gospel message, encapsulating the essence of Christ’s teachings in a manner that is profoundly accessible and universally applicable.

Doctor of the Church

One of the most remarkable aspects of Thérèse’s legacy is her designation as a Doctor of the Church by Pope John Paul II in 1997. The title is not merely honorary; it signifies that her writings are purportedly understood as orthodox and contribute significantly to Catholic theology. She became only the fourth woman to receive this title, joining the ranks of esteemed theologians like St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and St. Teresa of Ávila. The designation was particularly significant because Thérèse was neither a theologian in the academic sense nor someone who had lived a long life filled with grand deeds. Her “little way” offered a hopeful and biblical approach to Christian spirituality, making the pursuit of holiness accessible to everyone.

Conclusion

The legacy of Thérèse of Lisieux is a jewel in the treasury of the Catholic Church. A young Carmelite nun who lived a short, cloistered life became a highly regarded woman of holiness and a theological luminary through her love and humility. Her canonization and designation as a Doctor of the Church are acknowledgments of the extraordinary spiritual depth and theological richness contained in her simple, loving approach to God. In an age often given to the effects of post-modern inclination, Thérèse’s enduring message serves as a compelling reminder that the way to God can be as simple as a path of love, accessible to all in Christ, regardless of their state in life.

_______________________________________

1 The Story of a Soul, The Autobiography of The Little Flower (Charlotte: Saint Benedict Press, 1951, 1997, 2007, 2010)

2 Saint Thérèse of Lisieux and T. N. Taylor, The Story of a Soul (London: Burns and Oates, 1912), 319.

Comments are closed.